by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 18/12/2018

Categories:

Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

A visit to the Santo Chiodo Depot in Spoleto, a place built to shelter cultural property affected by natural disasters-a true hospital for works of art.

From the outside, it looks like an ordinary commercial shed, the kind that punctuates the image of a working and producingItaly. Here, too, of course, work is being done (and very hard and briskly, too): what changes is the content of this large concrete building. We are in Spoleto, visiting the Depot of Santo Chiodo, named after the locality of the same name where it is located, the industrial and commercial outskirts of the Umbrian city: inside, there is a treasure trove made up of thousands of works of art, those here sheltered after the collapses of the 2016 earthquake in central Italy. There are altarpieces, statues in marble, wood, terracotta, crucifixes, liturgical vestments, textiles, sacred furnishings, ceremonial objects, columns, bells, portions of frescoes, fragments of churches that had little or no power against the violence of the tremors that struck these lands between the summer and autumn of 2016. Taking care of them is a team of art historians, architects, archaeologists, restorers, and ministerial officials, replenished according to needs and emergencies, and engaged in a delicate activity: welcoming the works when they arrive, checking their condition, sorting them into the various departments of the Depot according to need (or sending them to restoration centers) and then cataloguing and filing them.

The need for a repository was realized after the disastrous earthquake of 1997, the one that has remained in the collective memory for the damage to the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi: a structure was needed that would be able to provide a very first reception of the works, already a few hours after the collapse, in a safe place, built according to the most stringent anti-seismic criteria, so as to give the technicians the possibility of activating in the most prompt and rapid way possible to ensure that the objects survive and be returned to their communities. Theprocess that led to the construction of the Depot of Santo Chiodo began in 1997 and ended in 2008: nine years, from the conception of the project to the inauguration of the Depot, to deliver to the country a modern and efficient structure, unique in the entire national territory, which gave the first proof of its solicitude on the occasion of the devastating earthquake in Central Italy, transforming itself into a kind of hospital for works of art, as well as a shelter for those left homeless. A structure managed by the Umbria Region and granted on loan for use to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage: a special agreement was signed between the two entities. Inside, on an area of about five thousand square meters, there is a first reception room, a large room where the works awaiting verification of their condition (and often arrive wet from rain or covered with snow, and are left here until a suitable accommodation is found for them) are temporarily housed, there are air-conditioned rooms, there are the racks for the preservation of paintings, there are the racks that house smaller statues, liturgical objects, and sacred ornaments, there are the pallets where the remains of collapsed buildings have been placed, there are areas used as archives, laboratories for initial interventions, there are the chests of drawers that house drawings and textiles, there is an anoxic chamber to remove pests and organic materials from damaged works, there is also a photographic studio.

In charge of the Depot is Tiziana Biganti, an art historian and MiBAC official. She welcomes us by tracing the history of the Depot of the Holy Nail: “It is a museum but it is a place full of suggestion,” she tells us. “The Depot is the center for the collection of works that come from the earthquake areas, it is a place set up in a really comprehensive way for the collection and care of works that need assistance. It is an extraordinary achievement that the Umbria Region and the Municipality of Spoleto chose to build after the 1997 earthquake, using a framework agreement project between the Municipality, the Region and the Ministry to create a well-equipped place, so that when the need arose to shelter cultural heritage in the moment of emergency, there would be a place already trained, prepared, like a clinic, a hospital, ready to receive these injured people.”

|

| Interior of the Santo Chiodo Depot in Spoleto |

|

| Tiziana Biganti |

|

| Fragments of the church of San Salvatore in Campi di Norcia |

|

| The first reception room |

|

| Drawers for the storage of tissues |

|

| The anoxic chamber |

|

| Racks for the conservation of paintings |

|

| The photographic studio |

|

| The intervention laboratory |

|

| The shelving for objects |

And the fact that the Deposit of Santo Chiodo represents a center of excellence is also evident from the fact that with the Deposit’s technicians collaborate restorers from theOpificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence and theIstituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro in Rome, Italy’s two highest public authorities on restoration, and in turn world excellences in the field. For the Opificio, the Santo Chiodo Depot has also become a training center: in 2018, thanks to an allocation of 130,000 euros from the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, ten young restorers who had just graduated from the Opificio delle Pietre Dure were able to carry out a year of “field work” right in the Depot. “We committed the excellence of the Ministry,” Tiziana Biganti declares. “So we have always acted very consciously. And also for next year we will welcome more restorers to continue this work: we have not exhausted the need for interventions.” But the excellencies are not only those who have been involved in the restorations. “As far as inventory filing is concerned,” Biganti adds, “the superintendence has involved a team of file filers with a call for bids. Filers who are now working both to catalogue and classify the heritage housed in the Depot and to implement the General Catalogue of Cultural Heritage. It is therefore a filing that has a double value, also by virtue of its function of acquiring notions about the works we house.”

The emergency phase lasted throughout 2018 and will end with 2019, the year in which the ordinary management of the Santo Chiodo Depot will be the responsibility of the Superintendency (and in the meantime, several interventions have been brought to a conclusion: several works have, moreover, already been displayed in exhibitions held throughout Italy). But in the early stages there were many people involved in the recovery operations. “When the works arrived,” Tiziana Biganti points out, “there was an external team formed by an official from the ministry, the Carabinieri from the Nucleus Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, the fire brigade, and the Protezione Civile, which was specially trained. And the latter, moreover, is a novelty of the last earthquake: for the first time, in fact, these volunteers had not only the means, but also the materials for packing, and they were trained to pack the works in such a way that even the transports did not cause further damage to the heritage.” The experience of the earthquake was horrible, Biganti points out. But the work at the Depot was a training model to be appreciated and disseminated as an excellence. “When the motivation is there, the teams work very well. In our case, all transfers from the territory to the Depot took place without damage and without dispersion.” And one of the characteristics that made it possible to act for the best was the speed of pickup. “After ten days we had the ability to go and pick up the works and take them away where the danger was not maximum and where we risked as little as possible. This was because we had the right location.”

|

| Interior of the Santo Chiodo Depot in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Santo Chiodo Depot in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Santo Chiodo Depot in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

|

| Interior of the Depot of Santo Chiodo in Spoleto |

The history of this place, however, has not always been the happiest. For eight years, from its opening until the 2016 earthquake, the facility was underutilized: controversy ensued, because to many it seemed an unnecessary expense, the Depot looked like a cathedral in the desert. So, before the earthquake, the region moved part of the archive there: however, in the aftermath of the August 24, 2016, quake, it became clear to all that the facility was useful. And that summer, the Repository was already free and ready to perform the function for which it was intended. “For months and months,” Tiziana Biganti recalls, “we have been here almost around the clock, and we have collected to date six thousand four hundred goods, including archaeological heritage, historical-artistic heritage, architectural portions.” It is a complex work from the moment the works arrive, because as soon as the goods arrive at the Depot, the first operation (one of the most delicate) is the compilation of the speditive surveys, the forms with which the goods and their origin are identified, the general state of maintenance is recorded, the type and extent of the damage suffered is described, and thus an initial diagnosis is provided that will serve to guide the next stages of the work, namely the securing, possible restoration, conservation actions, and finally the return to the place of origin. A work to be repeated for thousands and thousands of works, which led to the creation of a true analytical inventory of the injured heritage. “No one would have thought of such a numerical and even qualitative result,” Biganti stresses, “it was a demonstration and an awareness. And it was also an opportunity to compile cataloging of these assets, a way to deepen the very knowledge of this heritage.”

The presence of the Santo Chiodo Depot has really made a difference: a streamlined structure, ready to intervene quickly and effectively, equipped with all the professional units necessary for its operation, has made it possible to speed up the recovery time of the works. In this sense, Umbria has much to teach Italy and Europe as a reference model for emergency management. “Already after the first tremor,” Biganti says, “we moved to recover the works of the churches that were at risk of collapse, and fortunately there were only three, so those three were freed before the October 30 tremor brought everything down. We had the great good fortune to be able to act immediately, not only because the technical structure and the team existed, but also because the place of shelter existed.” The difference can be felt if you compare the work done in Umbria with the work done in the other regions affected by the earthquake, where the timeframe was longer because it was only later that all the shelter facilities had to be identified. Thus, the Santo Chiodo Depot immediately showed itself as an example of prevention that worked well and allowed technicians to work in an organized and efficient manner. “Having all the equipment available that is useful for the conservation and care of the works,” Tiziana Biganti points out, “the Depot is not only a place for conservation, but also for intervention and safety, and this allows us to immediately stop the deterioration of the works, which could be progressive. We also have the possibility to act both at the level of restoration interventions and at the level of study and filing of an immense heritage: this place, in fact, was designed for all of Central Italy, but then seven of the municipalities affected by the last earthquake completely filled it.” All municipalities in the Valnerina, one of the areas hardest hit by the earthquake. The size of the event also highlighted how large and varied Italy’s widespread cultural heritage is. “It is the real heritage, the uniqueness of the Italian territory,” Biganti says. “There are not only museums: the real uniqueness of our nation is the widespread heritage. Wherever we go, not only in Umbria but throughout Italy, we always find something of great value, and the great thing is to promote the discovery of this great heritage.”

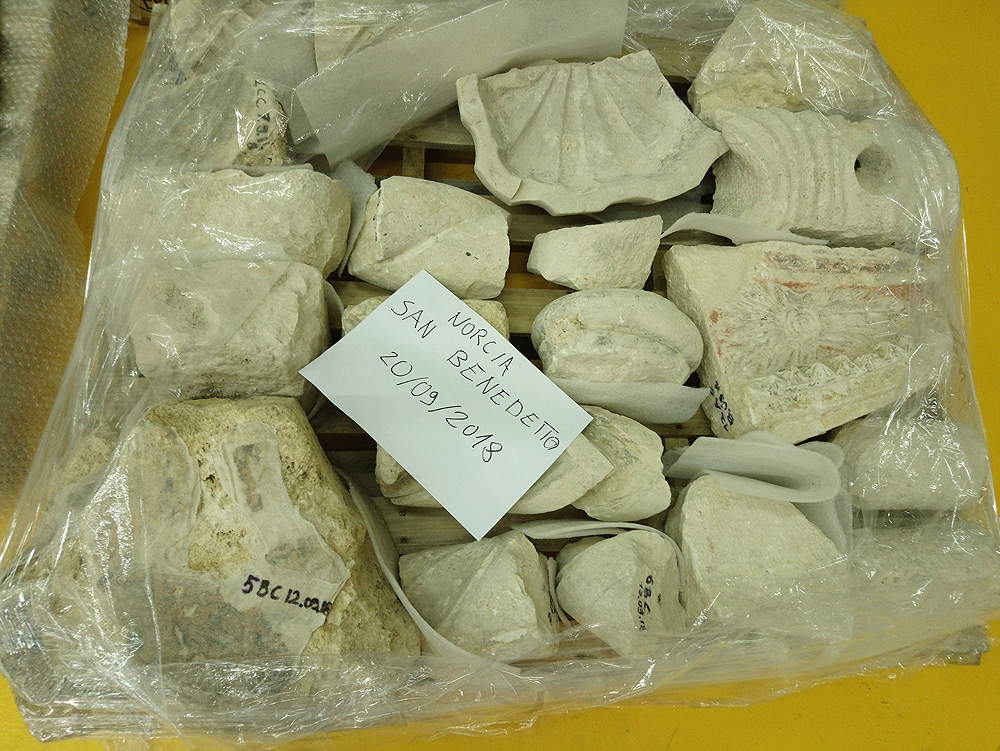

It is enough to take a tour through the large rooms of the Depot of Santo Chiodo to realize how vast this heritage is. Inside are the remains of the church of San Salvatore in Campi, one of the first to collapse. There are the fragments that came from the basilica of St. Benedict in Norcia. There are also several works of art from the basilica, including sculptures and altarpieces. There is a 16th-century masterpiece such as the altarpiece of theCoronation of the Virgin by Jacopo Siculo (Giacomo Santoro, Giuliana, 1490 - Rieti, 1544), dating from 1541 and coming from the church of San Francesco in Norcia. Also from Norcia here is the 17th-century Crucifixion of St. Peter, a canvas by Vincenzo Manenti (Orvinio, 1600 - 1674). There is the large altarpiece of the “Peace of the Casciani,” a 1547 work by Gaspare and Camillo Angelucci, admitted here from the Collegiate Church of Cascia. There are the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century canvases arriving from the church of San Pellegrino in Norcia, including two altarpieces attributed to Paolo Antonio Mattei of Cascia. And then a very large number of reliquaries, devotional statuettes, votive offerings, candlesticks, crucifixes of all sizes, thuribles, monstrances, aspersories, cartegloria, shrines, frames, and capitals.

|

| Works from the church of San Pellegrino in Norcia. |

|

| Fragments from the basilica of St. Benedict in Norcia |

|

| TheCoronation of the Virgin by Jacopo Siculo |

|

| The Peace of the Casciani family by Gaspare and Camillo Angelucci |

|

| The Crucifixion of St. Peter by Vincenzo Manenti |

|

| Mechanical organ from the church of San Procolo in Avendita |

|

| Madonna and Child in wood by an 18th-century Umbrian workshop, from the church of Sant’Andrea in Norcia |

|

| Work in restoration |

|

| Work in restoration |

|

| Work in restoration |

All the works, in the Depot, are brought together on the basis of their place of origin. If you walk through the rooms you will find yourself almost immersed in a forest of signs identifying the churches or buildings from which a certain group of goods came. Norcia and Cascia, even at first glance, seem to be the two municipalities most present. “Our terror,” Biganti explains, “was that the various trousseaus, once they arrived, could be confused, because on certain days as many as four or five deposits would arrive from different churches, and the trousseaus are all homogeneous. So a dispatchable list was prepared and an attempt was made to identify the trousseaus: then, with the analysis that was done on the various elements, they were sent either to the securing site, or to the Deposit for preservation.” Conservation, in the case of the Santo Chiodo Depot, does not, however, mean the end of the work’s life: the goods do not arrive here only to never leave the structure again. The goal of the Depot’s technicians is to return as many works as possible to their communities. And so the Depot is a living place, where everyone is committed to ensuring that this goal can be realized.

Meanwhile, local communities have developed a strong attachment to their heritage. An attachment that is growing more and more: the citizens of the towns affected by the earthquake are asking to see their works, and for the local communities the Depot is always open. “’Sacred,’” Biganti points out, “means endowed with a very high religious and devotional value. And this is especially for a population that has lost everything, that is often very attached to religion, and that sees as its only hope, perhaps, the fact of addressing a few prayers to images, to symbols that have always had exceptional value for them. The works that were saved from the earthquake have increased their saving power for these people. We may or may not believe this, but we have a duty to respect this sentiment. Thus, the Holy Nail Depot is open, first and foremost and at all times, to all communities in the area. And I will not hide the fact that many people ask for a specific work, they want to see it, they pray in front of it. They can check how it is: for them, it is like visiting a sick person in the hospital.” The relationship with the residents, however, has not always been easy. At first, admission to the Depot was felt almost as a confiscation, because for them the works could still represent hope. “So,” the Depot manager scolds, “we also made a personal commitment that we would welcome the local communities, and that they would have the opportunity to come here at any time. And now they even still call us to entrust us with goods that were initially housed at other facilities.” The Depot, however, is not only open to residents: everyone can go there, during visits that are organized on a roughly monthly basis. For the fall-winter of 2018-2019, for example, a program of guided tours has been organized, titled Open Depot, with four appointments between November 24, 2018 and January 12, 2019, each one dedicated to a thematic focus on the works housed in the Depot (the heraldic coats of arms, the wooden furnishings, the great masters of the 20th century, and the symbols of the City of Spoleto). If you want to stay updated on further appointments, you should consult the websites of the City of Spoleto and the Region of Umbria.

“We try to work for the best,” Biganti remarks, “in the one and only hope that this heritage returns to its places of origin, because it is a wealth that must be returned to the owner: if nothing else, this direction must be followed for the identity history of the communities.” There are also those who, perhaps because they are driven by the unfounded stereotype that equates a depot with a dusty warehouse, would like to see the Santo Chiodo Depot turned into a museum. “But we have so many museums, suffering, in great difficulty,” comments the head of the Depot, who also speaks as a museum director (she is in fact the head of the Villa del Colle del Cardinale Museum in Perugia and the Palazzo Bufalini Museum in San Giustino), who is familiar with the problems that plague our institutions, especially the smaller ones or those in outlying areas. “So we try to give back this heritage,” Tiziana Biganti concludes. “It is the real wealth of the area.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.