The figure of the She-wolf with twins occupies a foundational role in Siena’s imagery because it recalls the city’s legendary origins and embodies its deepest identity value. The animal’s watchful posture, combined with the vitality of the two infants, produces an image that blends protection and civic pride at the same time. The Sienese myth is thus intertwined with that of Rome: the She-wolf, symbol of the founding of the capital and nurturer of Romulus and Remus, becomes in Siena an emblem of Senio and Ascanio, the mythological founders of the city. The connection with Rome gives the figure a value of historical and political continuity, and transforms the sculpture into a true visual archive of the city’s memory. The Sienese She-Wolf, with its snout turned forward, claims iconographic autonomy from the Capitoline original, emphasizing the independence and pride of the Republic.

During the fifteenth century, several columns with the She-wolf sprang up in the various city tertiums, taking on political and symbolic functions, while the image appeared on coins and in ceremonial devices. The spread of the symbol strengthened the link with civic identity, also visible in public artworks, such as Ambrogio Lorenzetti ’s Buon Governo or Jacopo della Quercia’s Fonte Gaia, where the She-wolf dialogues with allegorical figures and references to Christian devotion. Over time, the She-wolf also became the object of adverse propaganda and political substitutions, as in Montepulciano with the Florentine Marzocco or in the medals of Cosimo I de’ Medici, but it always remained a founding symbol. Its presence in the contrade, city museums and the Palazzo Pubblico testifies to the enduring importance of the myth. The Sienese She-wolf is thus the centerpiece of the city, memory, myth and civic pride, where Rome’s influence serves as the legendary root and guarantor of historical continuity. Here, then, is where we can find her.

Made between 1429 and 1430, the bronze sculpture of the she-wolf by goldsmith Giovanni di Turino was created for the column at the right corner of the Palazzo Comunale. According to historian Dietmar Popp’s text, Lupa Senese. On the Staging of a Mythical Past in Siena (1260-1560), the bronze group, rested on a base adorned with the coats of arms of municipalities, districts and civic militia associations and was installed on a Roman column from the ruins of Orbetello. With such placement, the third symbolic pole of the city was defined, next to the cathedral and the municipal seat. The column area performed precise civic functions: justice was administered there, the public kennel was located, and proclamations were proclaimed from the Podesta’s loggia.

In 1959 it was removed and transferred to the Civic Museum to ensure its preservation. As anticipated earlier, the figure of the she-wolf occupies a central role in the Sienese imagination, as it recalls the legendary origins of the city. The work, conceived during a decisive phase in the maturation of local Renaissance figurative culture, displays a calibrated naturalism and formal balance that mark Turino’s detachment, from the last remnants of Gothic taste. The sculpture is currently located in the Museum’s vestibule, a room created in the 19th century in an area once used as the sacristy of the Lords’ chapel. The vaults and walls were decorated in the nineteenth century following fragments found during renovation work. The room also houses memorabilia related to the town’s history and the Palio, including four seventeenth-century clarions of German manufacture and the helmet of the Capitano del Popolo.

The carved and gilded hood datable to between 1473 and 1516 (displayed in the view of the antechamber of the Consistory in the Museo Civico, whose current neo-Gothic guise dates from a 19th-century intervention, as recalled by the date 1882 on thecentral archway) is attributed to Antonio Barili, an artist active between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, who combined skill as a wood carver with architectural expertise, incorporating trends in Sienese Renaissance sculpture into his figurative repertoire.

The long sides of the hood show two eagles and two affronted griffins, set in elegant acanthus scrolls, enclosing the party coat of arms of the Comune di Siena and the Capitano del Popolo, while the short sides bear the coat of arms of the Tribunale di Mercanzia. At the corners, four figures with lion heads and female bodies testify to the virtuosity and finesse of the carving. The lid, decorated with a vegetal frieze and raised in the center, is embellished with a sculpture in the round of the She-wolf with twins.

During the fifteenth century several columns dedicated to the She-wolf sprang up at different points in the city. In 1464 a marble column was erected at Camporegio in memory of the Palio dedicated to Blessed Ambrogio Sansedoni. In 1470 another column was installed in the horse market at the ancient Porta San Maurizio. In 1487 one appeared in Piazza Postierla to mark the junction of the Via del Capitano leading to the Duomo. The three columns were then distributed in the three city Terzi: Camollia, San Martino and Città, probably to represent their administrative structure.

Similar columns also arose in the centers of Sienese rule. A specimen from 1474 is preserved in Massa Marittima Cathedral; another, intended for Sovana, is documented by a 1469 payment to the craftsman Urbano da Cortona, as Popp writes in his text. In Montepulciano a columnar monument, now lost, housed the She-wolf until 1511, when it was replaced by the Marzocco imposed by the Florentine rulers. In Grosseto, in the nineteenth century, a column without a figurative crowning was placed as an urban sign and originally probably housed the symbol of the city. Many of these monuments disappeared as political changes made their symbolic value intolerable.

The She-wolf present in Piazza Tolomei, on the other hand, embodied an eminently political significance and represented the sovereignty of the Republic. The image of the animal with twins, placed on a column, took on the same value as coins minted from 1510 onward, where it appeared on the reverse. The legend “SENA VETUS CIVITAS VIRGINIS” enveloped the city symbol, while the obverse showed the cross accompanied by the formula “ALPHA ET O PRINCIPIUM ET FINIS.” The She-wolf thus ended up replacing the simple “S” of early coinage issues. Only from the 1630s did the image of Our Lady begin to take the place of the animal symbol.

In the Republican period the She-wolf with the twins became a true identity manifesto, also present in works intended for civic propaganda. A drawing accompanied by a text, made by Mariano di Jacopo known as Taccola between 1431 and 1433, presents the She-wolf as the patron saint of Siena consecrated to the Virgin and protector of the citizens, entrusted to Emperor Sigismund during his stay in the city in 1432. Taccola’s treatise, dedicated to Sigismondo, celebrates his role as defender of Sienese freedom and symbolically contrasts imperial authority with the Florentine Marzocco. A similar conception characterized the ephemeral apparatuses set up for the entry into the city of Charles VIII of France on December 2, 1494: three celebratory arches featured the motto “Sena Vetus Civitas Virginis,” the She-wolf welcoming the sovereign and symbolic figures such as Charlemagne. The main themes of Sienese identity, Marian protection, legendary origins and welcoming the Christian king, were forcefully reiterated.

The presence of the She-wolf in broader figurative programs is attested as early as Jacopo della Quercia ’s Fonte Gaia of 1414-1420, which introduces a further reminder of the legend of the city’s origins: two female statues with children, interpreted as moral or mythical figures, recall antiquity, while the spouts of the font depict the She-wolf in harmony with the Madonna of the reliefs.

Drafts of Jacopo della Quercia’s drawing of the fountain, preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, document the detailed design of the fountain before its execution in marble. The original drawing on parchment depicted the complete sculptural ensemble, with allegorical figures, animals and plant ornaments, including the She-wolf, symbol of the legend of Siena’s origins, placed in the foreground. Two female figures with infants, Acca Larentia and Rea Silvia, allude to the mothers of Romulus and Remus, linking pagan myth and civic identity. The sketches show meticulous work, with precise lines, washes and ink strokes suggesting the three-dimensional volume of the sculptures. Missing or unfinished parts, especially on the right side, reflect the progress of the project around 1415-16. The drawing also reveals Jacopo’s training as a goldsmith and the late Gothic practice of Sienese drawings, predating Renaissance perspective.

The statues of the font, together with those of the She-wolf, made by Della Quercia between 1414 and 1418 and preserved at the Fondazione Antico Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala, thus created a link between pagan myth and Christian devotion that long defined Sienese identity. A similar example, as Popp reports in his text, appears in the Loggia della Mercanzia, where Antonio Federighi sculpted in 1464 a bench adorned with a She-wolf placed at the center of a series of civic emblems and moral, mythological and religious references. The sculptor Giovanni di Stefano, son of the painter Sassetta, on the other hand, left to Siena the two marble suckling she-wolves of the Porta Romana, now preserved inside the Fondazione Antico Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala. At the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo we find instead the 13th-century Giovanni Pisano ’s She-wolf suckling the twins and the She-wolf suckling the twins, an expression of the post-sixteenth-century Sienese school.

The She-wolf also assumed a polemical role in representations of Siena’s enemies. In 1511, in Montepulciano, it was replaced by the Florentine Marzocco. After the fall of the Republic in 1555, Cosimo I de’ Medici had a medal made representing the She-wolf tied to a palm tree with the inscription “SENIS RECEPTIS,” a clear sign of submission. During the duke’s triumphal entry into Siena in 1560 the She-wolf appeared at the feet of the personifications of Siena and Florence, united in the new Medici Tuscany: an image that, in the eyes of the Sienese, sanctioned the loss of independence.

With the end of the Republic, the symbol took on more heraldic or ornamental forms and lost its original political role. In any case, Siena always remained deeply attached to the myth of the She-wolf, considered an integral part of its historical, cultural and religious identity. The adoption of the Roman She-wolf arose as an immediate response to a war event but quickly became a lasting memory.

Indeed, the sculpture of the She-wolf with twins, powerfully inspired by the ancient world, became a veritable archive of the city’s history. Reproduced for centuries, it evoked both the city’s legendary origins and more recent achievements. In Rome the She-wolf recalled the capital’s roots; in Siena it took on a new meaning, linked to the legend of Senius and descent from the founders of Rome. The Sienese She-wolf, unlike the Capitoline one, has its snout turned forward, a detail that accentuates its iconographic autonomy.

The She-wolf finds some of its most evocative expressions in Siena Cathedral and its square, where it also stands out on the top of a column. The city’s main religious building, it dominates the panorama along with the Torre del Mangia and, according to tradition, rose to replace a church dedicated to Mary built in the 9th century on a votive temple to Minerva. It was consecrated on November 18, 1179, by Pope Alexander III, a native Sienese.

One of its best-known features is the floor composed of fifty-six marble inlays executed in commesso. The decorations follow designs by Sienese masters such as Domenico Beccafumi and foreign artists such as Pinturicchio. In the nave, immediately after the figure of Hermes Trismegistus, appears the She-wolf suckling twins. The inscription “Sena” points toward Ascanius and Senio, but the presence of the fig tree points more clearly to the myth of Romulus and Remus. Around them appear the heraldic animals of the main cities of Tuscany and central Italy: horse (Arezzo), lion (Florence), panther (Lucca), hare (Pisa), unicorn (Viterbo), stork (Perugia), elephant (Rome), and goose (Orvieto). Four additional animals occupy the corners of the panel: lion with lilies (Massa Marittima), eagle (Volterra), dragon, griffin (Grosseto). It is the only sector of the floor made with mosaic technique. The present work dates from 1865 and is the work of Leopoldo Maccari; some fragments of the 1372 original are preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

The legacy of the city’s founding myth is also reflected in the tradition of the district that bears its name, where the image of the animal takes on a profound identity value, visible as much in the heraldic emblems as in the ritual spaces and daily paths of the neighborhood. The coat of arms, in silver, depicts a bigemine Roman she-wolf on a grassy bell, crowned in the ancient style, with a silver and red border decorated with crosses. The contrada colors are black and white with orange lists. The baptismal font, made by Giovanni Barsacchi in 1962 and placed outside the Church of San Rocco in Vallerozzi, houses a bronze she-wolf modeled by Emilio Montagnani.

The contrada also has a museum that tells its story and houses the sacred furnishings of the Compagnia di San Rocco, which came into the contrada in the late 18th century. Renovated and reopened to the public in 2002, the museum includes the hall of representation, the archives and the monture room.

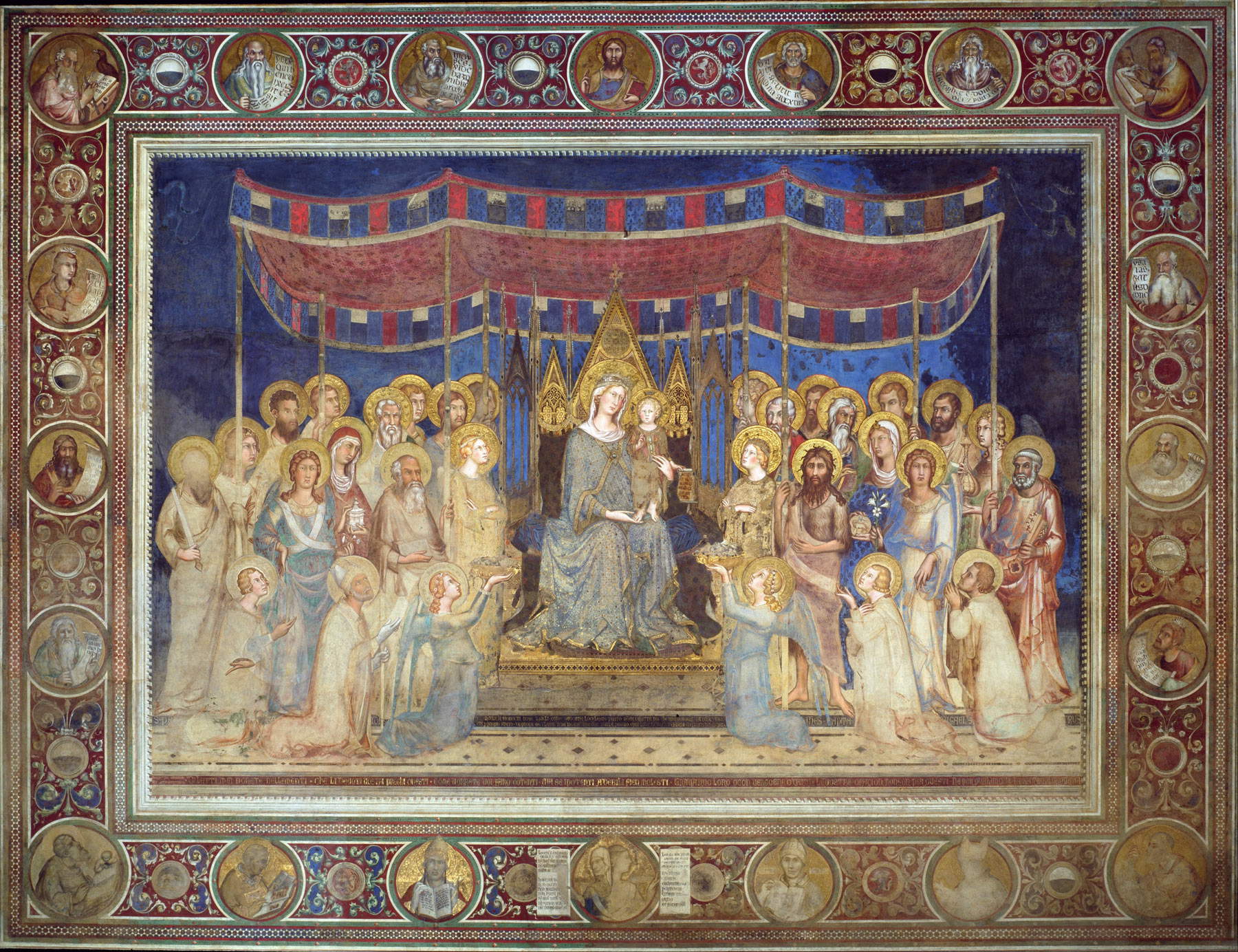

Finally, in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico the She-wolf with twins appears in several symbolic contexts. In Simone Martini’s Maestà, included in the lower band along with the seal of Siena, the Balzana and the rampant lion of the People, it reiterates the link between founding myth and civic identity. Similarly, in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco, Allegory of Good Government (1338-1339, Sala della Pace), the symbol of the city emerges at the end of the procession of citizens: the She-wolf with twins. Above it looms the Municipality of Siena, represented by a monarch in majesty with the inscription C[omunis] S[enarum] C[ivitas] V[irginis], dressed in black and white and adorned with motifs reminiscent of the Balzana, the city’s well-known symbol.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.