For more than six centuries, the waters off Copenhagen in Denmark have held a ship destined to redefine knowledge of navigation and trade in the Middle Ages. The discovery involves Svælget 2, the largest medieval crock (a type of ship in use during the Middle Ages) ever found, which was spotted in the Øresund Strait during preventive archaeological investigations related to the Lynetteholm urban project. The wreck, unearthed by maritime archaeologists from the Vikingeskibsmuseet in Roskilde, offers new information on early 15th-century ship technology and the organization of trade in northern Europe. The find occurred in the stretch of sea between Denmark and Sweden, one of the main maritime arteries of the Middle Ages. From the first dive, archaeologists realized they were dealing with something out of the ordinary. As sand and sediment were gradually removed, the outline of a ship of exceptional size emerged, far beyond those of the nocks known so far.

“The discovery represents a milestone in maritime archaeology,” says maritime archaeologist and excavation leader Otto Uldum. “This is the largest nock known to date and offers a unique opportunity to understand both the construction and life aboard the largest merchant ships of the Middle Ages. A ship with such a large cargo capacity was part of a structured system in which merchants were aware that there was a market for the goods they carried. Svælget 2 represents a concrete example of the development of trade in the Middle Ages. It is clear evidence that even everyday goods were traded. Shipbuilders made ships as large as possible to transport bulky goods, such as salt, lumber, bricks, or staple foods. The Cocca revolutionized trade in northern Europe. It made it possible to transport goods on a scale never seen before.”

The ship, named Svælget 2 after the channel in which it was spotted, measures about 28 meters long, 9 meters wide and 6 meters high, with an estimated cargo capacity of around 300 tons. Built around 1410, it is thelargest documentedexample of this type of vessel ever. According to archaeologists, the ship’s size reflects a phase of profound economic and social transformation: building and operating a merchant ship of such proportions presupposed established trade networks, efficient port infrastructure and highly specialized labor organization. The cocca was a relatively simple ship to operate, even when fully loaded, and required a surprisingly small crew. It was precisely these characteristics that favored its spread as the main means of transport for long-distance trade between the North Sea and the Baltic. The large cocques were designed to tackle the dangerous passage around Skagen and cross the Øresund, linking ports in the Netherlands with Baltic merchant cities. Svælget 2 fits fully into this context, offering a firsthand account of the networks that united northern Europe in the 15th century.

The importance of the cog as a super ship of the Middle Ages lies in its ability to transport large quantities of goods at relatively low cost. This change had decisive consequences for economic dynamics. While previously long-distance trade was reserved mainly for luxury goods, with the introduction of large vessels it became possible to ship even everyday goods over vast distances. The ship found in the Øresund thus represents a key element in understanding the evolution of trade systems between the 14th and 15th centuries.

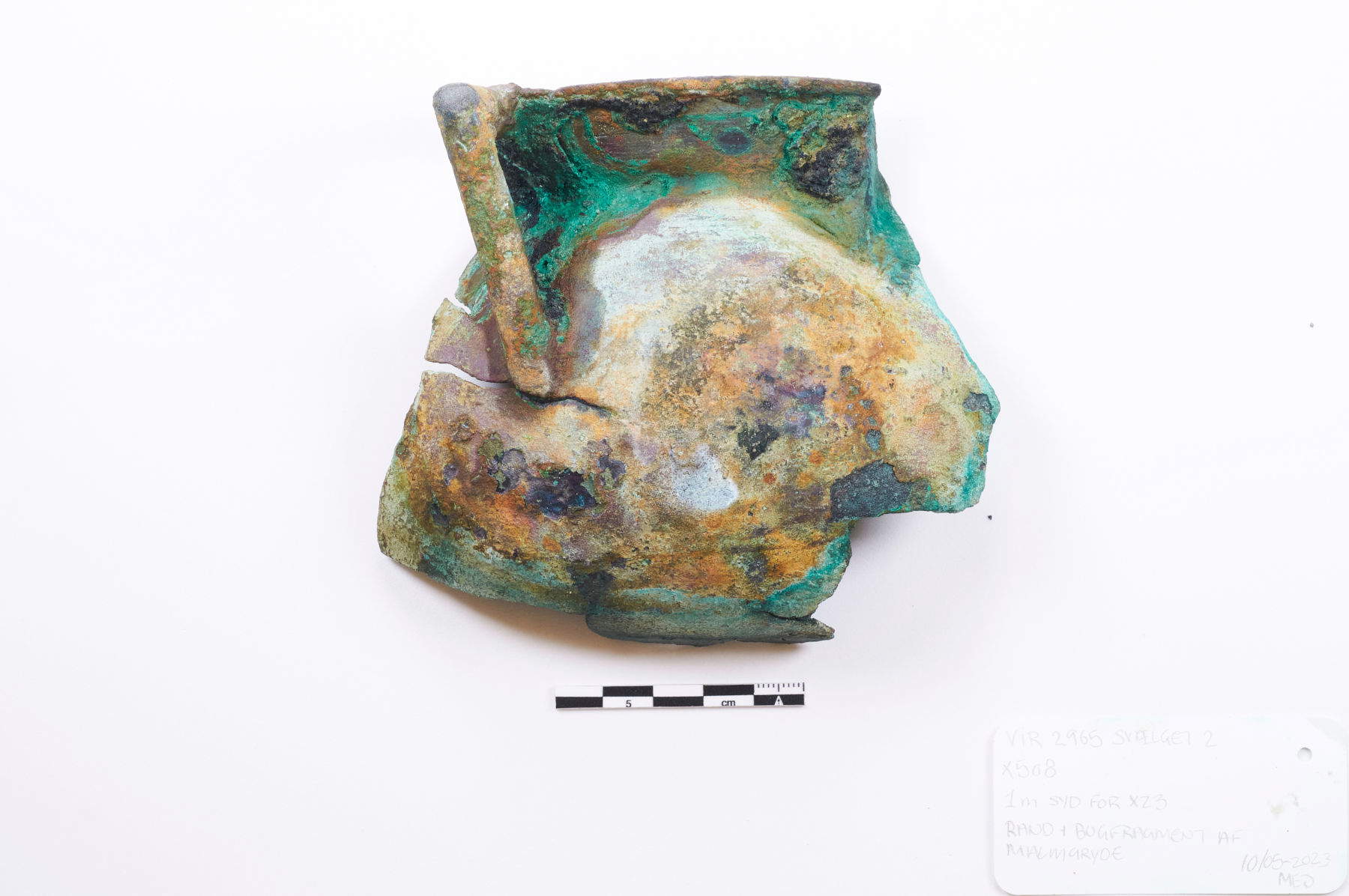

Dendrochronological analyses (the method that studies the annual growth rings of trees) conducted on the wooden remains have made it possible to accurately date the construction of the vessel and to identify the origin of its materials. The lumber used came from two distinct areas: Pomerania, in present-day Poland, and the Netherlands. The planking boards are made from Pomeranian oak, while the frames, which form the ship’s framework, are derived from Dutch lumber. This combination suggests an articulate building practice, based on the import of large quantities of heavy timber and local processing of other components, a sign of an efficient and well-organized trade network. One of the most remarkable aspects of Svælget 2 concerns its state of preservation. The wreck lay at a depth of about 13 meters, in an environment that protected it from currents and destructive agents typical of coastal areas. The sand preserved in its entirety the starboard side from the keel to the capodibanda, a condition never before documented for a medieval cocca. Important traces of sailing equipment also emerged in this area, allowing scholars to analyze in detail hitherto little-known technical solutions.

The discovery also provided concrete archaeological evidence for the existence of the tall wooden structures at the bow and stern, known as castles, depicted in numerous medieval iconographic sources but never so clearly documented. In the case of Svælget 2, archaeologists have identified extensive remains of a real stern castle, a covered structure that provided shelter for the crew. According to maritime archaeologist Otto Uldum, this is a particularly important discovery, as it provides insight into how these elements were constructed and used on board. A further innovation is the discovery of a masonry galley, the oldest so far documented in Danish waters. The area designated for cooking included about 200 bricks and 15 tiles, and allowed for a fire to be lit on board. Bronze vessels, ceramic bowls and the remains of fish and meat were found in the same area, attesting to the crew’s dietary practices. Numerous finely crafted sticks, probably used for stockfish storage, also emerged.

Excavations have also returned items related to daily life on board, including painted wooden crockery, footwear, combs and rosary beads. These materials offer a rare insight into the living conditions and internal organization of a large merchant ship. The presence of cooking utensils, tableware and personal items testifies to a prolonged stay at sea and the need for efficient management of resources. The question of the cargo carried by Svælget 2 at the time of the shipwreck remains open. So far, no direct traces of the cargo have been found, only items traceable to the ship’s crew or equipment. According to Otto Uldum, the absence of recognizable cargo can be explained by the fact that the hold was not covered: barrels of salt, bales of textiles or cargoes of lumber could have easily floated and dispersed during the sinking. The lack of ballast also suggests that the ship was fully loaded with heavy goods. Despite the absence of any evidence of military use, there is no doubt about the vessel’s mercantile function. Svælget 2 represents concrete evidence of an evolving society in which the growth of maritime trade required ever larger ships and complex commercial infrastructure.

“There are numerous depictions of the bow and stern castles, but until now they had never been found because usually only the lower part of the ship survives,” Otto Uldum continues. “This time we have the concrete archaeological evidence. Today we have twenty times more material than in the past. This is not comfort in the modern sense of the word, but it is a significant advance over the ships of the Viking Age, which had only open decks, exposed to all weather conditions. In Danish waters, a masonry galley on a medieval ship has never before been documented. This is a feature that testifies to a remarkable level of comfort and organization on board. Sailors could consume hot meals, similar to those on land, instead of the dry, cold food that had hitherto characterized life at sea. The sailor carried a comb to keep his hair in order and a rosary for prayers. The pots in which food was cooked and the bowls from which food was eaten remain. These personal items show that the crew embarked with them elements of daily life, transferring the experience ashore to that at sea. We did not locate any traces of the cargo. There is nothing among the many artifacts found that cannot be interpreted as personal items of the crew or ship’s equipment. There is no evidence to indicate war or conflict in this ship. None at all. There was a need for a social system capable of financing, building and arming these huge ships, designed to meet the long-distance export and import needs of the Middle Ages. Perhaps the discovery does not change the picture we already know about medieval trade. It does, however, allow us to say that it was ships like Svælget 2 that made that trading system possible. Today we know without any doubt that coteries could reach this level of size, pushing this ship type to its extreme limits. Svælget 2 offers a concrete building block for understanding how technology and society developed in parallel at a time when shipping was the engine of international trade.”

The archaeological work was funded by By & Havn - Copenhagen City & Port Development as part of work on the Lynetteholm district. The ship’s remains are currently undergoing a lengthy conservation process at the National Museum in Brede. The discovery is the focus of the documentary series Gåden i dybet, produced by Danish public broadcaster DR, which is being programmed on DR2 and available for streaming on dr.dk. The public can also follow research developments and observe the work of archaeologists up close at the Vikingeskibsmuseet in Roskilde, where activities and exhibitions dedicated to Svælget 2 will continue until 2026.

|

| Wreck of largest medieval ship ever found emerges off Copenhagen |

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.