Almost half of what is preserved at the Brera Art Gallery is due to the ideas and taste of a man, Andrea Appiani, who was well regimented within the Napoleonic bureaucratic apparatus. Right from the start: as early as 1796, the year of Napoleon’s arrival in Milan, Appiani had become an instrument of Napoleonic propaganda, an artist of the regime, a court portrait painter, and then on the snowy 19th day of the year V, i.e.January 8, 1797, he had been invested with his first official post, that of judge of the Fine Arts, charged with choosing, we read in the documents of the time, “those monuments which may be worthy of an exception in the general abolition of feudal and noble insignia.” Then, in 1802, at the time of the Napoleonic spoliations, would come the appointment as commissioner of Fine Arts: he would have to choose, census, and classify the works that had become national property as a result of the confiscations carried out towards the churches and guilds that the Napoleonic regime had dissolved throughout the territory of the newly established Italian Republic. So there is also Appiani’s hand on much of today’s Italian cultural landscape. And this is perhaps one of the reasons why, for so long, Appiani was relegated to oblivion, if not openly dismissed as a minor artist: in 1954, Paolo D’Ancona believed that his artistic figure had been positively distorted by his supporters, “because they wanted to see in his work only a resurrection of theantiquity worthy of being on a par with that which David was accomplishing in France and, without delving into the diversity of the two temperaments, they exalted precisely of the Appiani artist his deterrent side, that is, that which resolves itself into a skillful descriptivism and a rhetorical glorifying symbolism.” An artistic judgment, to be sure, that found Appiani’s best in the works of his early production, with its echoes of Correggio and Domenichino, and yet provides a valuable summary of how the Milanese painter was viewed for a long time.

Prior to the exhibition that, this year, Milan is dedicating to Andrea Appiani, the production of Italy’s leading neoclassical painter had been investigated on a single, pioneering occasion, between 1969 and 1970: a small review at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan, which had been the only monographic exhibition on him before the present Appiani. Neoclassicism in Milan, curated by Francesco Leone, Fernando Mazzocca and Domenico Piraina at Palazzo Reale, in the Appartamento dei Principi, the most suitable place to host an exhibition on Appiani. It is the second stage of a review organized together with the Musée national des châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau, which hosted the debut. That this exhibition, an exhibition on an Italian artist, started in France is a curious fact up to a point, since Italy, to be frank, has never loved Andrea Appiani very much, despite the consideration of his contemporaries, who thought of him as a kind of Raphael redivivivus, especially in fresco painting: Leopoldo Cicognara, for one, wrote in 1809 that “Europe does not have among the living an artist who succeeds better in fresco painting than Signor ca. Andrea Appiani.” His close association with Napoleon undoubtedly weighed in. Behind the surface of the regime’s cantor, however, lies the complexity of the man who, Roberto Paolo Ciardi has written, "was on his own account as much in a favorable psychological disposition to behave unscrupulously toward the aristocratic privileges of theancien régime, as much as provided with a secular spirit so as not to be hamstrung by religious scruples; a situation not to be underestimated, if one considers that not a few administrators of the Napoleonic government showed insuperable difficulties not only in carrying out requisitions of works of art already owned by religious guilds, but even in breaking into places of worship." On the one hand, Appiani had in the past had his moments of clashes with the academic circles of Austrian Milan, however much he could hardly claim to be an artist alien to the court’s favor. And his landing in Napoleon’sentourage had been similar, in every way, to that of Jacques-Louis David, who until the day of the French Revolution worked for the king, and who had then switched with the most casual ease, almost out of the blue, to painting portraits of revolutionaries. On the other hand, it must be said that the idea that dwelled in Napoleonic cultural circles at the time of the spoliations was to safeguard the works, not to take them away: the fear, admittedly completely unfounded and deliberately exaggerated, was to see the crowds lash out at the symbols of the old regimes, at anything that might remind them of the oppression of the Church and past tyrants. This was not the case (on the contrary: in many parts of Italy the inhabitants of villages and towns tried to react to the looting), but it is not certain that Appiani knew this and that he was not really convinced that he had been put at the head of a saving mission. Fact is that Appiani was one of the most facultative interpreters of his time, as much in official roles as in painting.

The curators of the Palazzo Reale exhibition are not afraid to attach the label of “neoclassical” to Andrea Appiani, something that their French colleagues, on the other hand, have carefully avoided for David at the exhibition being held at the Louvre at the same time as this one in Milan (a dodging, that of the French review, which was not very successful and also not very thorough, as has already been argued on these pages). To Leone and Mazzocca, therefore, the merit of not having wanted to refuse boxes and definitions that, even with their limitations (one could just mention here that neoclassicism was not a monolithic movement, but the same could be said, for that matter, for all the movements in the history of’art), are, moreover, also useful in understanding Appiani’s scope and value, and the Palazzo Reale exhibition well reconstructs and well highlights his role as a profound innovator, even before that of Napoleon’s premier peintre , a qualification, this yestoo reductive to give an account of the importance of an artist who has long been in the canon of our art history, but who has perhaps never really been studied as he deserved.

That youthful production that earned Appiani even the timid praise of detractors is all explored in the first part of the exhibition, where the curators have punctually investigated the artist’s beginnings in Enlightenment Milan, in the Milan of Verri and Parini (and Parini, by the way, would become a good friend of Appiani: the exhibition also features a pair of his pencil portraits, one from the front and the other in profile), in the Milan of the bourgeois salons where the young painter, having discarded his eighteenth-century wigs (we see him with tousled hair in a pencil self-portrait together with some friends, included in the section devoted to Appiani’s image, to which is entrusted with the task of offering the public a sort of introduction to the exhibition), he began to paint keeping in mind the teachings of his mentors, of the professors he had followed at the Brera Academy courses (above all Giuseppe Traballesi and the Tyrolean Martin Knoller), and above all of the classics and modern painters to whom he seemed much more attracted. Appiani, for example, developed a passion for Correggio that led him to travel around the churches of Parma to jot down, fix in his memory everything he could see of Correggio: in 1791, at the age of twenty-seven, he wrote to one of his masters, Giocondo Albertolli, that he had felt “enraptured” by Correggio’s frescoes. This sixteenth-centuryism of his mixed with the recovery of classical models, producing composed compositions with restrained rhythm and brilliant, delicate coloring, reverberates in his earliest known productions, among which it is worth mentioning the four ovals with the stories of Venus that givenno start to the review, four paintings conceived together, now preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera, which offer the most vivid idea of the first phase of Appiani’s art, assuming one wants to go along with the subdivision of the scholar Francesco Reina, who was among Appiani’s earliest exegetes and who in one of his manuscripts had imagined three distinct periods in the artist’s career: one, characterized by a “style [that] has somewhat of the dry,” from the beginnings until 1792, the year in which Appiani was engaged in the frescoes of San Celso in Milan; a second period of the “natural and graceful” until around 1804-1805; and finally the last part, that of the “beautiful and ideal always accompanied by grace.” This is a subdivision with which Francesco Leone himself agrees, since it is evident that the artist, roughly concurrently with the San Celso frescoes, oriented his directions toward a painting less compliant with his models.

To realize this, before arriving at the room where the San Celso drawings are displayed, the exhibition offers a comparison between a pair of luminous oil-on-copper works from the late 18th century, both with mythological subjects(Aurora and Cephalus and the Rape of Proserpine), where a more cursive, loose and spontaneous painting preserves a clear seventeenth-century echo, and the four tempera paintings dedicated to the histories of Europe, which are from the mid 1980s and were painted by Appiani for Carlo Ercole Castelbarco Visconti Simonetta, marquis of Cislago, works of rare composure where everything is calm, measured, where any element seems to have to follow a calculated geometry, where any feeling (the lightheartedness of the scene of the nymphs playing with the bull, or Europa’s dismay in the abduction scene, and again the pain at the moment when Venus arrives to console her) seems to have to remain restrained, suggested, almost buried. Of course: not that Appiani was ever a slabbish, immoderate, chaotic artist. There is, however, a sort of hiatus, a sensation that is also felt as the journey continues, observing the fracture, the distance between a work such as the Madonna and Child, considered an early work (it is, moreover, one of Appiani’s rare sacred works executed outside ofa commission for a church) and the same drawings for San Celso, or again the drawings and models for the frescoes of Palazzo Passalacqua or those for the decorations intended for the small temple attached to the Milanese residence of Count Giovanni Battista Sannazzari della Ripa, the last works executed for the nobility of Habsburg Milan, works in which, under a patina of graceful levity, there is a spontaneity that provokes movement, that provokes a tension.

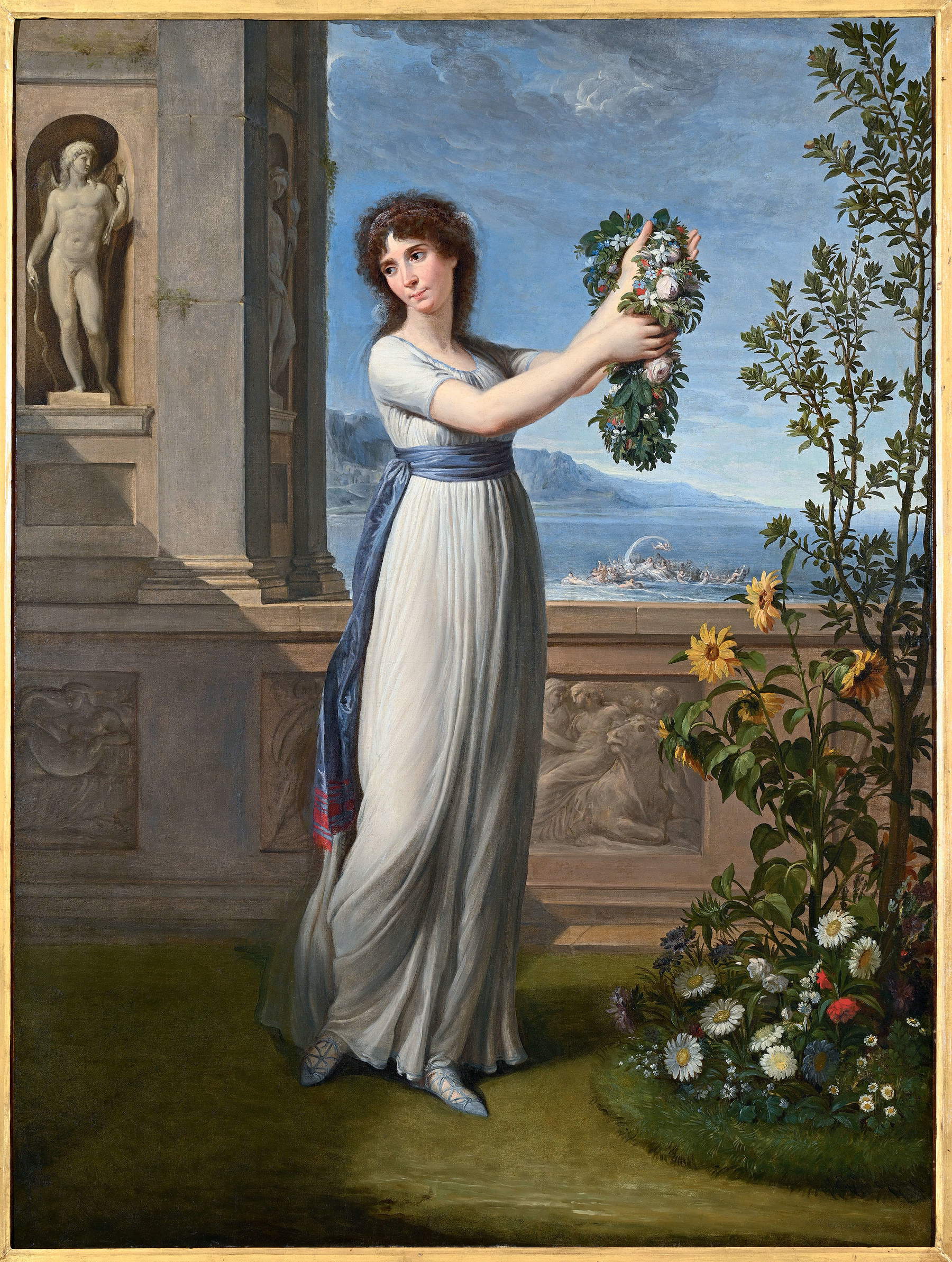

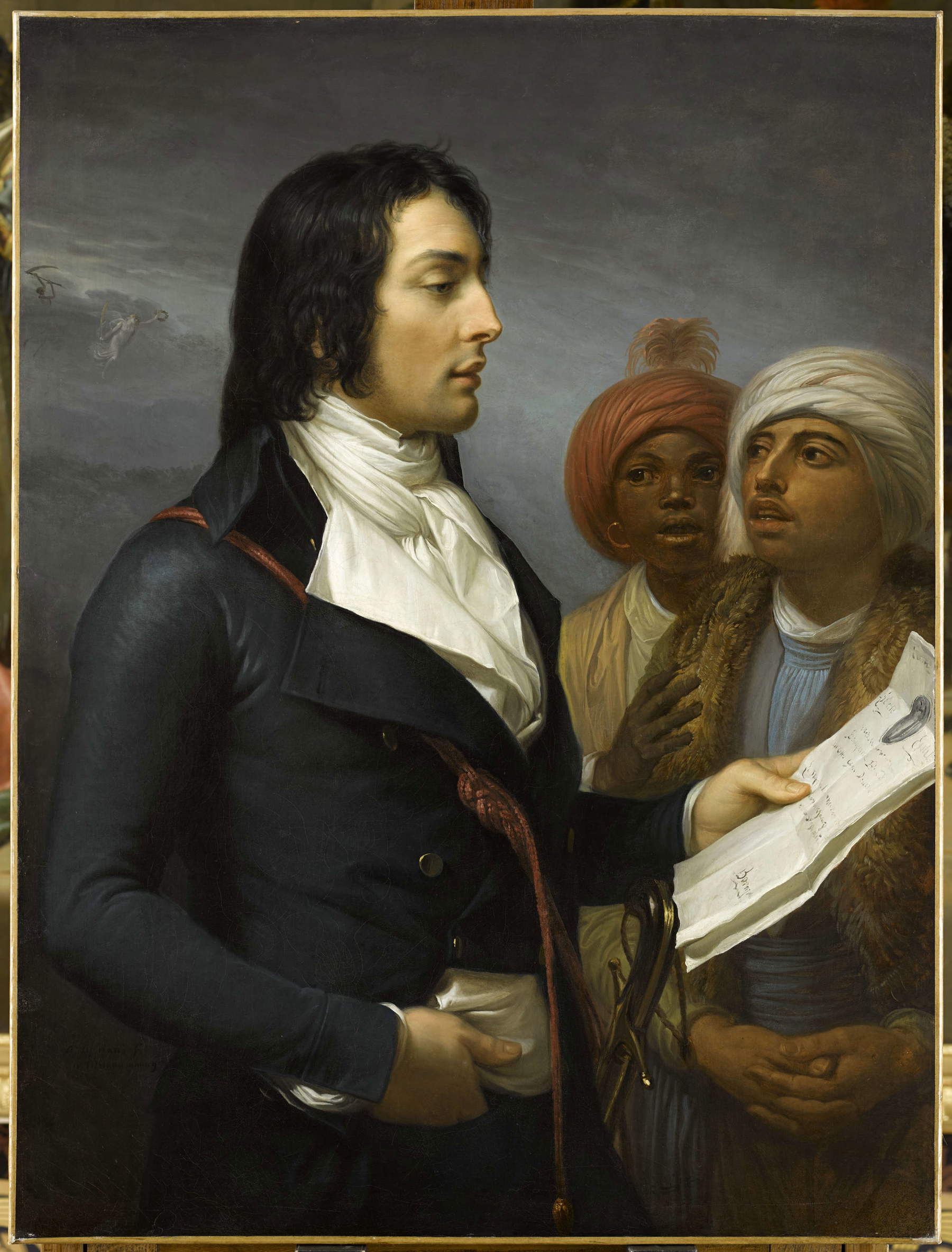

This is the same spontaneity with which Appiani would become Napoleon’s painter. The first historically ascertained portrait of the future emperor is his work and is on display in the exhibition: Appiani painted it shortly after Bonaparte’s entry into Milan, on the orders of General Hyacinthe Despinoy, and it depicts Napoleon in the guise of a general of the French army as he observes and at the same time incites the Genius of Victory who is engraving on a metal shield his exploits, against the background of the Battle of the Bridge of Lodi which is being fought in the distance. At the Royal Palace, the painting, which came on loan from Dalmeny House in Edinburgh, is displayed alongside what is considered its pendant, namely the portrait of Joséphine de Beauharnais painted when she joined her husband Napoleon in Milan in July of that same 1796. One can sense, even here, a qualitative gap: Joséphine’s portrait appears less stereotypical, more monumental, more animated (the diagonal cut of light on the left is one of the most interesting elements in all of Appiani’s portraiture), more alive, probably because Appiani had more time to think and finish it, as opposed to Napoleon’s portrait, which was instead executed almost in real time.

The Appiani painter of Napoleon and then, from June 7, 1805, officially appointed Premier peintre is, essentially, a portrait painter: this is the genre in which he reached some of the pinnacles of his production, albeit with a different quality than that of the French portrait painters. Appiani has always been a more graceful and less descriptive artist than Napoleon’s other painters, and perhaps this constant pursuit of “ideal beauty” has penalized him (some critics have considered him a less interesting painter than a David or even a Gros or a Gérard). There are inevitably pieces that appear more conventional than others (see, for example, the two portraits of Francesco Melzi d’Eril), but even when he seems more staid than a David, Appiani is seeking a synthesis between the new and the old. And his portraiture therefore reaches heights that others are precluded from. The portrait of Fortunée Hamelin, for example, is a modern and lively translation of the Mona Lisa. That of Giuseppina Grassini is enlivened, as was the case in seventeenth-century portraiture, by an episode that is glimpsed in the distance and is probably an allegory of the love between Napoleon and the singer, who is moreover caught in a pose almost identical to that of Bernardino Luini’s Flora in the Royal Collection. Some portraits convey the character’s temperament with supreme economy of means: it happens, for example, in the portrait of Napoleon as president of the Italian Republic, or even better in the portrait of Count Teodoro Lechi, which shows one of the most vivid and profound looks in Appiani’s portraiture. Even a posthumous painting like the portrait of General Desaix avoids homologation to conventional production. Then there are unusual solutions, as in the previously unpublished portrait of Francesca Milesi Traversi: the woman’s back is turned and she is caught turning toward the relative after evidently contemplating a vast mountainous landscape. And then there is large-scale official portraiture that is close to that of French contemporaries: this is the case, for example, with the portrait of Giuseppe Arborio di Gattinara, minister of the interior of the Kingdom of Italy, or of Achille Fontanelli, minister of war and navy (that of Fontanelli is one of Appiani’s last works, executed in 1813, the year in which he was struck down by a stroke that would prevent him from continuing to work). They are idealized images, to be sure: in all of them, however, one is given to find, writes Fernando Mazzocca, “that naturalness that will always be distinctive of Appiani’s portraiture and that saves these images from rhetoric.” And it was this naturalness, combined with a mediation between the instance of fidelity, however idealized, to the real subject and the recourse to the classical model, that made Appiani the most relevant portraitist of Italian neoclassicism. “Rather than the antique,” Mazzocca continues, “he seems to be inspired by a ’real’ derived from a probably direct relationship with his models and a link with local genius that led him to draw on his beloved Leonardo and Luini, as well as Correggio and Parmigianino.”

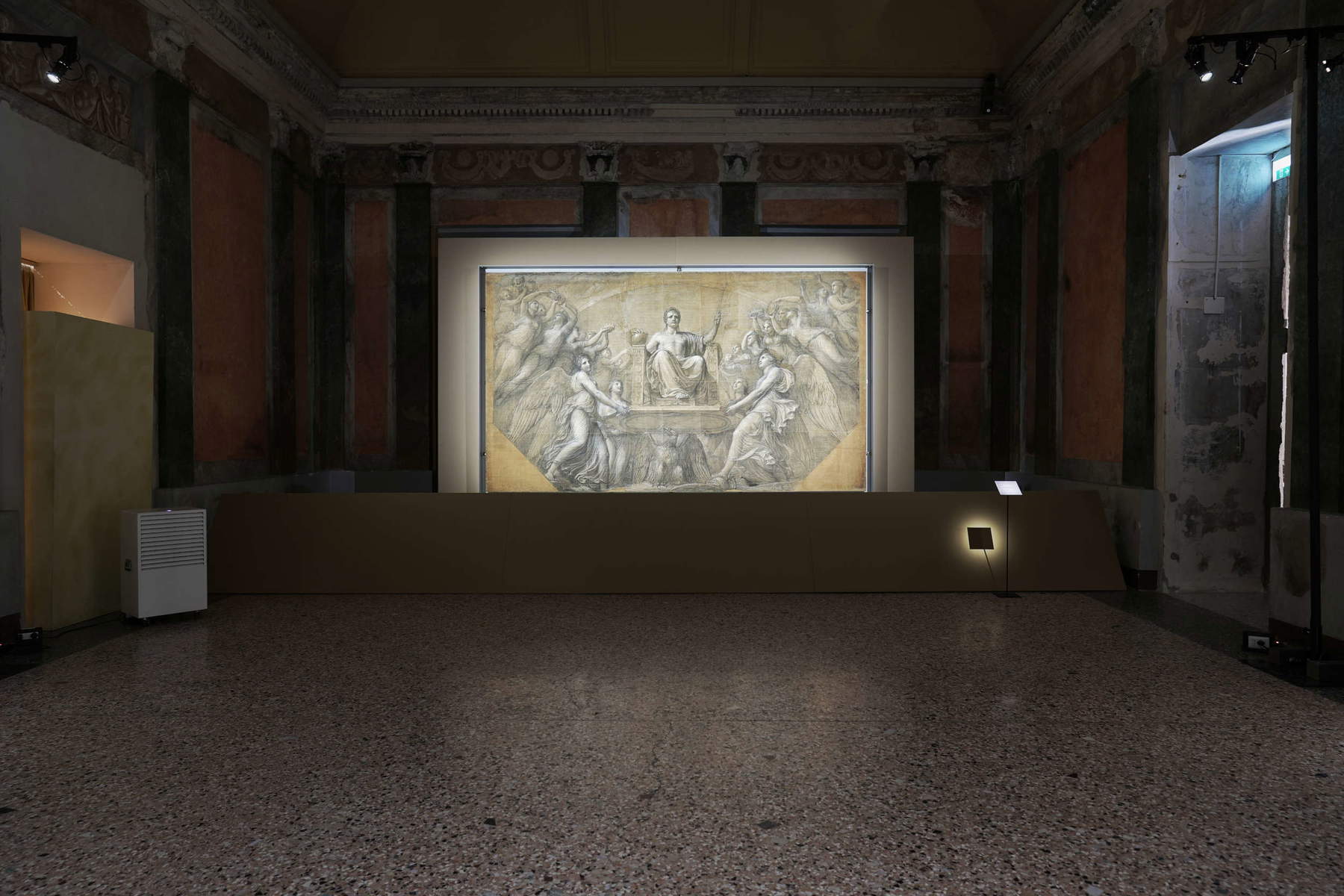

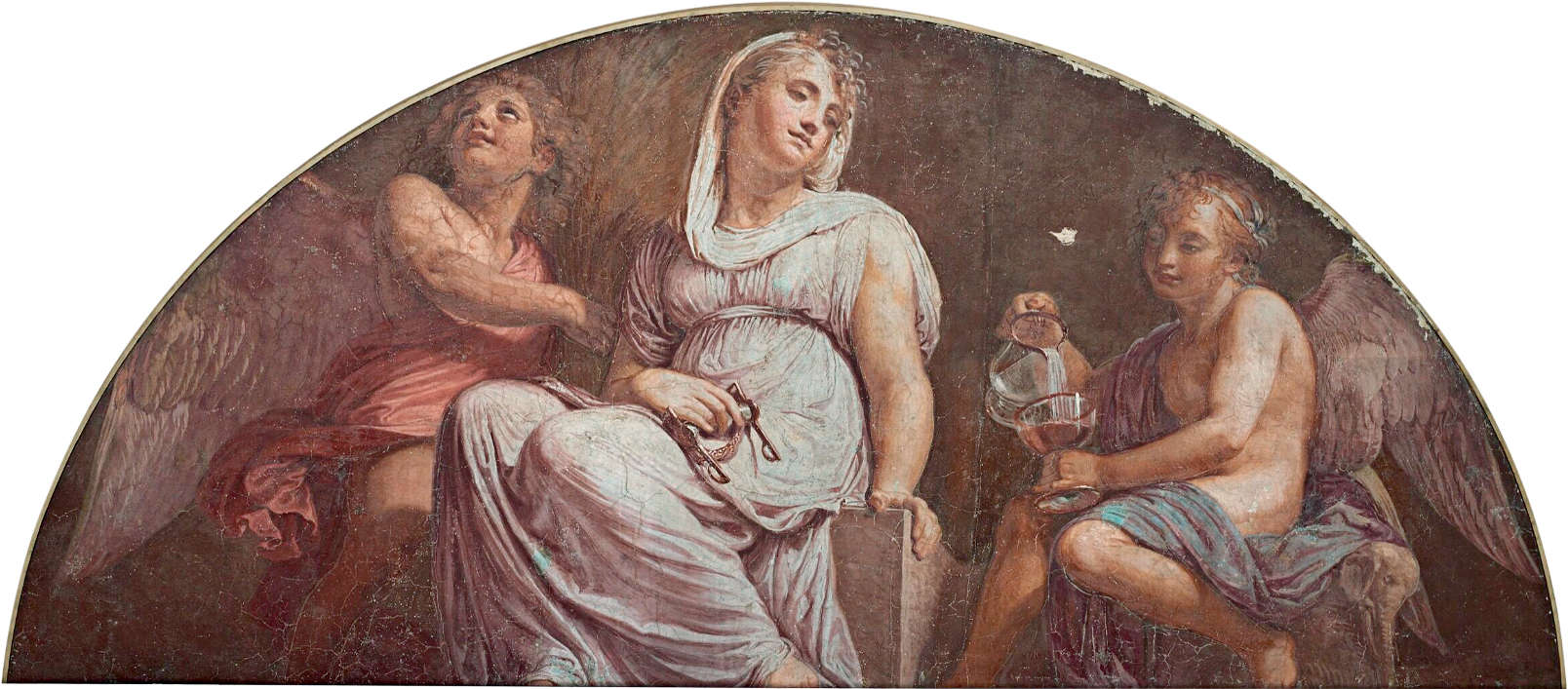

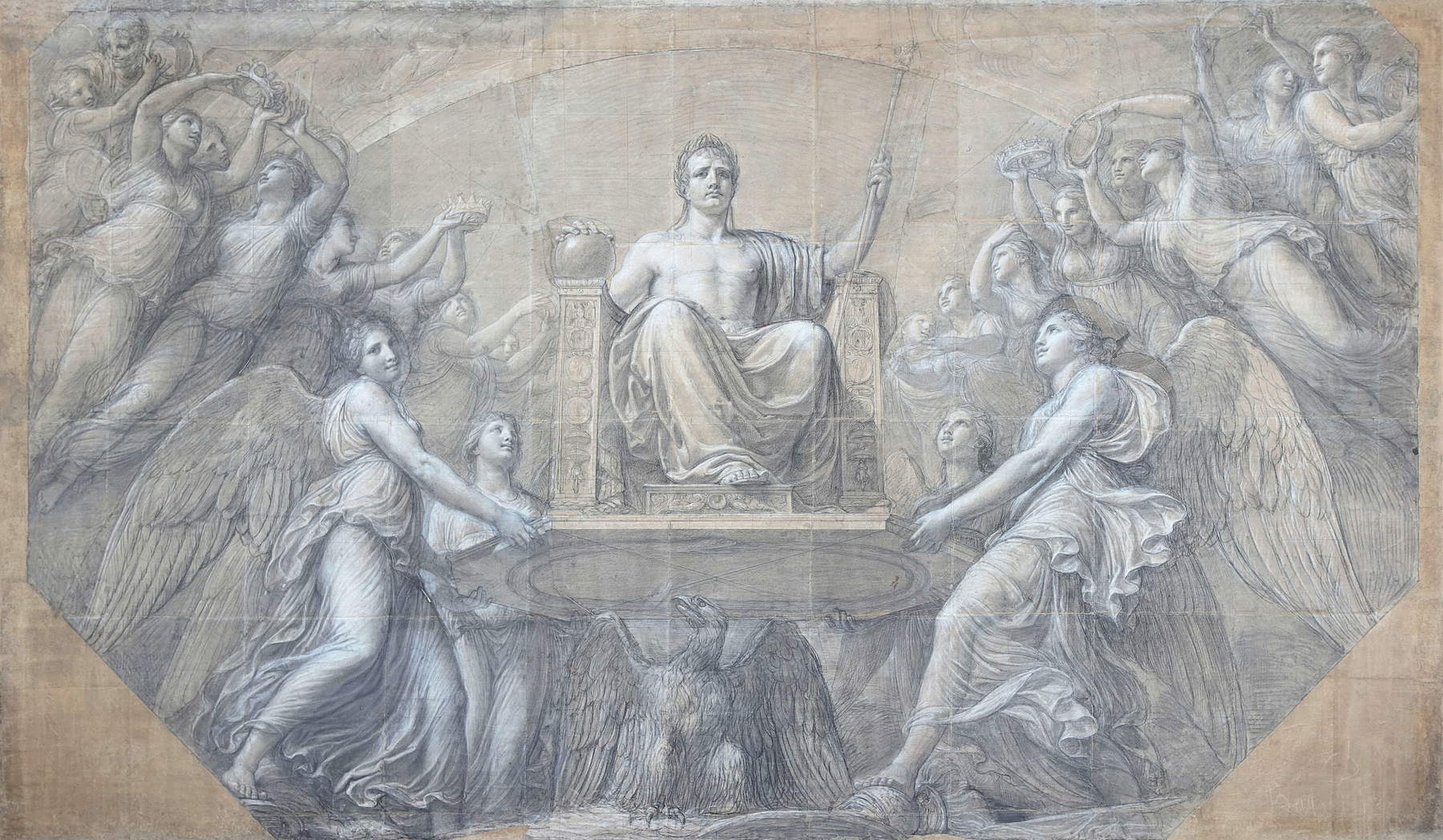

The tour comes to a close by showing some of the happiest results of the last third of the career of the “painter of the Graces”: the two canvases that were part of an unfinished cycle on the love between Jupiter and Juno, destined for the Royal Palace, stand out. The two paintings would later remain in the possession of Appiani’s heirs, and today one is at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia and the other in a private collection. For Francesco Leone, these two paintings are to be considered, together with the Parnaso frescoed at the Villa Reale in Monza, the “aesthetic testament” of Appiani’s painting, which touches here the culmination of the phase of his production in which, writes the curator, “grace and the natural were projected into a courtly dimension that responded to the canons of ideal beauty inspired by ancient statuary.” And they are also, one might say, the trait d’union with the last two rooms, which are all dedicated to Appiani’s undertakings in the Royal Palace, which precisely because of this strong connection with the painter could not but be the most suitable place to host a major exhibition on him. What Appiani had painted for the palace was unfortunately irretrievably lost during the bombings of World War II: the frescoes painted in 1805 for the Throne Room were almost totally destroyed, and the cycle of the Fasti di Napoleone, the extraordinary sequence of canvases painted in grisaille for the Sala delle Cariatidi between 1800 and 1807 to celebrate the exploits of the first consul during the Italian campaign, was lost in its entirety. They could have been saved, since they were canvases that were easy to transport, so much so that in 1815, when the Austrians returned to Milan, they were immediately removed from the Sala delle Cariatidi, and were then installed again in 1860, after the entry into Milan of Victor Emmanuel II, who had wanted to pay homage to the French allies by having Appiani’s frieze put back in its place. They could have been saved, but they were not: in the exhibition catalog, Simone Percacciolo traces in great detail the events of 1943, when Gino Chierici, then superintendent of Milan, prepared an effective plan to safeguard the works that could be moved, thus succeeding in protecting much of the heritage of the Royal Palace and establishing a model that would later be adopted on a national scale as well. The plan, however, did not include the Fasti, which remained in the Sala delle Cariatidi and were therefore incinerated during the bombing: "the failure to save the Fasti,“ Percacciolo writes, ”thus represents a jarring anomaly, still lacking a definitive explanation today. Who knows that this long and troubled affair, intertwined with the very history of the protection of Italian heritage, may yet hold unexpected and astonishing surprises, capable of shedding light on the fate of Appiani’s works and on the choices and priorities that guided the protection strategies in a dramatic era for Europe and for cultural heritage.“ The last part of the exhibition is dedicated, then, to the ghosts of what is no longer there. First the visitor will find the remains: In the room where the centerpiece of the Coronation, the sumptuous work by Roman mosaicist Giacomo Raffaelli executed on commission by Melzi d’Eril for the dinner celebrating Napoleon’s coronation as King ofItaly, one finds the four allegories of the cardinal virtues that once decorated the Throne Room and accompanied the effigy of the king seated on his throne, and which are the only surviving fragments of the decorative apparatus (today they are preserved at the Villa Carlotta in Tremezzina). Then, here from the Louvre is the imposing preparatory cartoon, almost five meters long, for the vault of the Throne Room, a glorifying, solemn work, in which Appiani, even within such rhetorical overkill, ”does not deviate“, write Corisande Evesque and Rémi Cariel, ”from the fluidity of his own style and assigns a significant prevalence to the feminine element through the allegorical figures of Victories and Hours painted on the corners of the vault." Next, the drawings for the Lantern Room of the Royal Palace, which was to be decorated with images of episodes of virtues from antiquity. Finally, in the Sala delle Cariatidi, the entire frieze of the Fasti was faithfully reproduced for the exhibition with one-to-one scale prints on canvas, because fortunately photographs taken before the bombs rained down on the ceilings of the Royal Palace were preserved: the effect, then, is to find oneself once again in the midst of the apparatus designed by Appiani, who even in a work with such a blatantly celebratory tone had tried to’offer a solution of his own, a mediation between the needs of the propaganda of the time, which needed modern and recognizable images, and adherence to a model that was inspired instead by the friezes of Roman classicism, by the course and rhythm of ancient reliefs, of Roman columns: the result was a work in which the narrative of Napoleon’s battles and the rhetoric of allegories unfolded in a vivid, harmonious, idealized but at the same time enlivened, if not actually excited, whole.

Appiani’s fame was certainly also conditioned by the loss of what could be admired of him inside the Royal Palace: to the disinterest in the season that saw him excel was added the destruction of what he had left in the place that had been the symbol of Napoleonic power and that today is little more than a shadow of how it appeared in Appiani’s time. We no longer have his masterpieces, we no longer have what he had painted for the halls of the palace, we no longer have the masterpieces of that artist who, Pelagio Palagi said, had no equal as a fresco painter, and to find someone worthy to stand beside him we had to go all the way back to Raphael. Stendhal, after seeing the Throne Room, had written that France had produced nothing comparable. Much of the praise had come from those who had seen what Appiani had done inside the Royal Palace, which can no longer be seen today. The arrival of the cartoon from the Louvre, restored especially for the exhibition (at a 70-thousand-euro expense covered by the Biofer company) was hailed on the eve of the show as a kind of epoch-making event, complete with press following the transport and installation and amidst the enthusiasm of the city council. And then, the lunettes loaned from Villa Carlotta will remain at the Royal Palace on a permanent basis, to try to at least partially make up for what can no longer be recovered, to try to cover with a thin veil of foundation, as much as possible, a wide, deep scar that has disfigured the face of the Royal Palace.

The attempt is admirable, and crowns a comprehensive exhibition, an exhibition of rediscovery, an exhibition that even has the courage to identify Milanese neoclassicism all in the figure of Andrea Appiani, since, despite the title that juxtaposes the artist’s name with the movement, no works by his colleagues appear in the itinerary. An exhibition that, above all, has the merit of not hiding complexity. Perhaps it will not be enough to make Appiani more interesting, let us not say more sympathetic, to the Italian public, but in everyone’s defense it could be said that ours are not times of classical grace: today people prefer a Caravaggio or an Artemisia, they want to see on their canvases screams, violence, theater, blood. They want to see on paintings what they don’t want to hear about in life, basically. For Appiani’s ideal beauty there is little room.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.