In 1958 the famous American magazine Life devoted an extensive feature to sculptor Louise Nevelson (Kiev, 1899 - New York, 1988) on the occasion of Moon Garden Plus One, or that exhibition held at the Grand Central Moderns Gallery that would represent a decisive turning point in her artistic career. Immortalized in the midst of her 116 “sculptures in a box” (an environmental installation characterized by a strongly evocative black and white that invades the scene with the exception of her figure and some surrounding sculptures bathed in a green tint), Louise Nevelson wears a pointy hood in a theatrical representation of her creative act as if it were “a kind of artistic witchcraft.”

The following year, the eccentric Nevelson, at the age of sixty, during Art USA 1959 hosted at the New York Coliseum, won the sculpture prize awarded to her by a jury consisting of the likes of Lloyd Goodrich, Charles Cunningham, and Clement Greenberg. That same year the Museum of Modern Art included her work in the exhibition Sixteen Americans, placing her work alongside such notable names as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Frank Stella. In 1962 she was selected to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in the midst of what can be considered a rising career that would see the artist’s work acquired by major international museum collections such as Moma and the Tate.

To her, “Grande Dame of 20th-century sculpture,” the Renaissance Palazzo Fava is dedicating a significant monographic exhibition, the first so far in Bologna. Promoted by Associazione Genesi in collaboration with Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna and Opera Laboratori di Firenze, it is part of the Genus Bononiae cultural program. The Genesi Association, committed to protecting human rights, established in 2020 by the will of President Letizia Moratti, was created with the aim of addressing social issues such as the women’s issue, racism, victims of genocide, and climate urgency through the universal language of contemporary art: after the first 3 years in which it exhibited its collection in different venues in what was the Genesis Project (which ended last December), it has inaugurated from this year a new cycle aimed at rediscovering historicized artists who were anticipators of social issues that have become urgent. The figure of the Ukrainian naturalized American artist, with whom the association opens this new chapter, on the occasion also of the 100th anniversary of her migration to Maine to escape the persecutory climate against Jews that was spreading in the country, anticipates some topics particularly felt by thebody, from the ecological and recycling theme, to that of memory, to the women’s issue addressed through her personal experience as a woman, mother and then artist who asserts herself in a male-dominated society with work that is, quoting Germano Celant “feminine and feminist.”

The exhibition curated by Ilaria Bernardi does not set out to be a synthesis of Nevelson’s work, so much as a’critical interpretation of her art through a selection of works ranging from the 1950s to the 1980s, seen as the result of the alchemical process that led her to enact a redemption through the powerful medium of art, despite her disadvantaged starting condition as a woman of the 1940s and thus perceived like her peers as subordinate to men and relegated to the management of the family and the care of children.

The act of taking discarded and abandoned woods from the streets, modifying them, painting them black white and gold, assembling them and ennobling them corresponded to magical and evolutionary act, to which she had subjected herself and from which other women, by emulation, could take example to transform themselves “from vile metal into gold” and thus accomplish social redemption. And this is what the young woman does when she moves with her husband Charles to New York where she studies music, attends theater classes and avant-garde galleries; to him, from whom she will divorce in 1941, she leaves the care of her son Mike to follow her ambitions and go to study in Switzerland at Hans Hofmann’s courses and then embark on a series of trips to Salzburg, Italy and finally Paris, where she visits the Musée de l’Homme, which allows her to approach African art and deepen her knowledge of Cubism. Returning to New York she worked as Diego Rivera’s assistant on the mural in the New York Workers School and then devoted herself almost exclusively to sculpture (at first in terracotta and stone inspired by pre-Columbian art but making the works homogeneous thanks to a black casting as will happen with the wooden work, her material of choice almost “animated,” so much so that she states “I speak to the wood and the wood responds to me”).

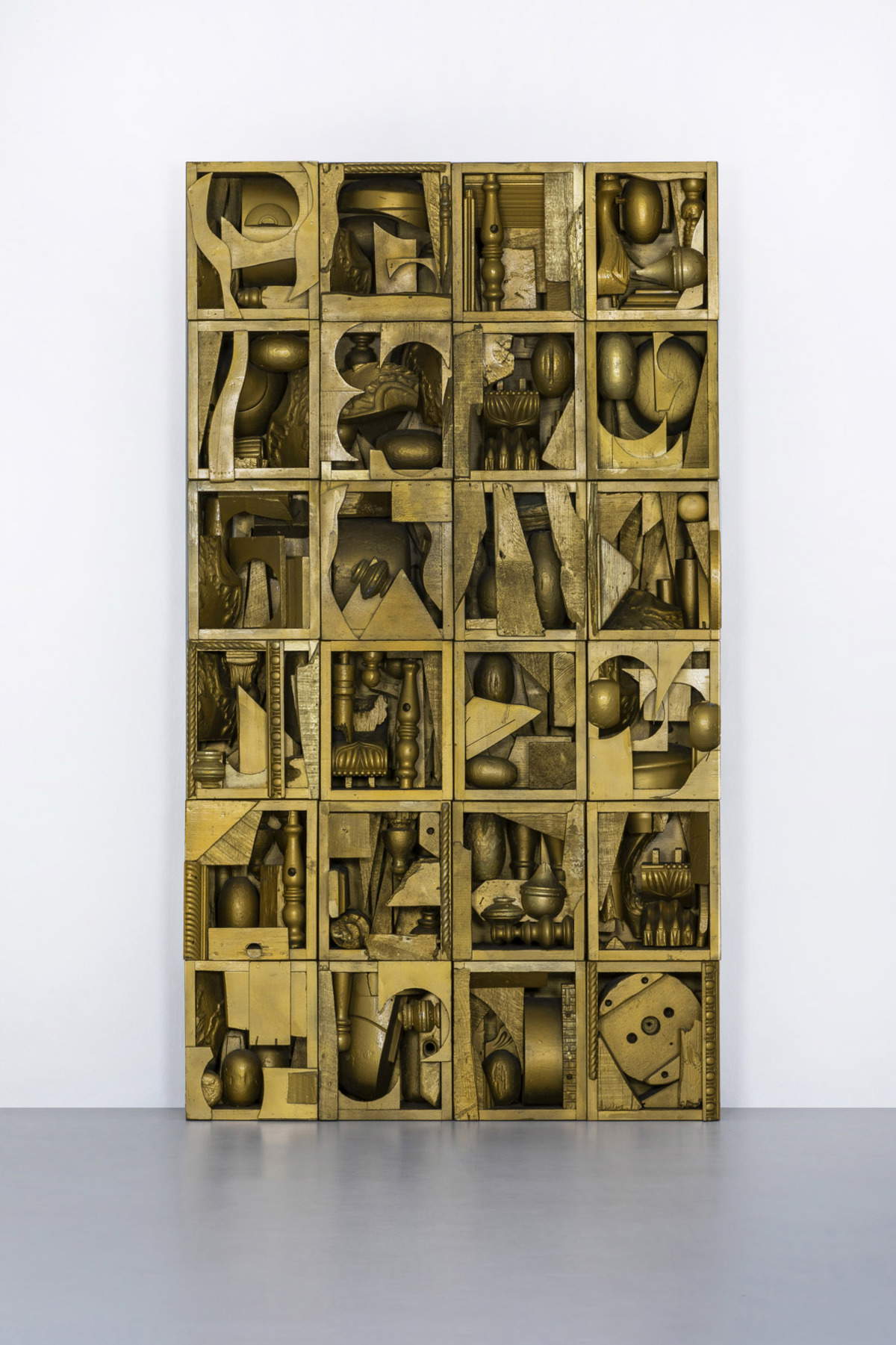

It is precisely from the famous freestanding sculptures painted entirely in black (perceived not so much as non-color as total color, a noble color that contains them all and that she will use until the end despite the introduction of white and gold), almost always untitled, that the exhibition hosted in the five rooms of the piano nobile frescoed by the Carracci opens. These works made up of objet trouvé of discarded wood assembled in a harmonious way, with a modular and repetitive appearance, with vertical and horizontal developments formed by boxes grouped together almost as if they were real shelving units inside which objects, spheres, cubes, chairs, pieces of tables but also numbers with cabalistic assonances find their place, are made from the 1940s and then in a more systematically in the Fifties, taking on the forms of more complex structures, later defined, sculptural architectures (in climate with the monumental art then in vogue); dominated always by an evident frontality, in a chromatic zeroing that renders the individual pieces homogeneous and indistinguishable, as if to suggest a sort of “initiatory death” for their resemantization in tune with the artist’s desire to disengage from the role of wife and mother in order to be born to new life. These are works that never achieve the two-dimensionality of sculpture in the round, but rather result as “sculpted paintings” made up of solids, voids, light, and shadows.

The idea of working with abandoned wood seems to have sprung from her when she came across a piece of wood submerged in mud on the street, but in fact the attachment with this material, which symbolizes the beginning of a rebirth and the start of a rising artistic path, has deep roots: her grandfather in Ukraine was a forest and timber owner while her father worked in construction. In the 1950s the artist is said to have accumulated some 900 pieces of wood in his Manhattan home, so much so that to make room he even crammed them inside his bathtub. In his autobiography, he wrote, “I wear cotton clothes so that I can sleep or work with them, I don’t want to waste time.... Sometimes I could work two, three days and not sleep, and I paid no attention to food, because a can of sardines, a cup of tea and a piece of stale bread seemed so good.”

The exhibition itinerary from the Giasone room continues in the Rubianesca room, which houses some examples of the so-called wooden doors made from the mid-1970s onward (with the exception of a 1955 work that originated as a sampling of a small door, probably from a cellar, later modified, which becomes a precursor to the series made later). The artist adds everyday objects to them such as backs, chair legs, all unified by black color, and suspends them on the wall as if they were real paintings, to mark the desire to elevate to Art works built with salvaged elements. The door in Alchemy is a significant element because it represents the union of opposites, where matter and spirit come together; but it can also be understood as a portal within a transformative process in which Opus reaches its conclusion. The door for Nevelson becomes at the same time a magnet that collects all the discarded elements of domestic life and corresponds, almost like a visual synecdoche, to the traditionally understood woman.

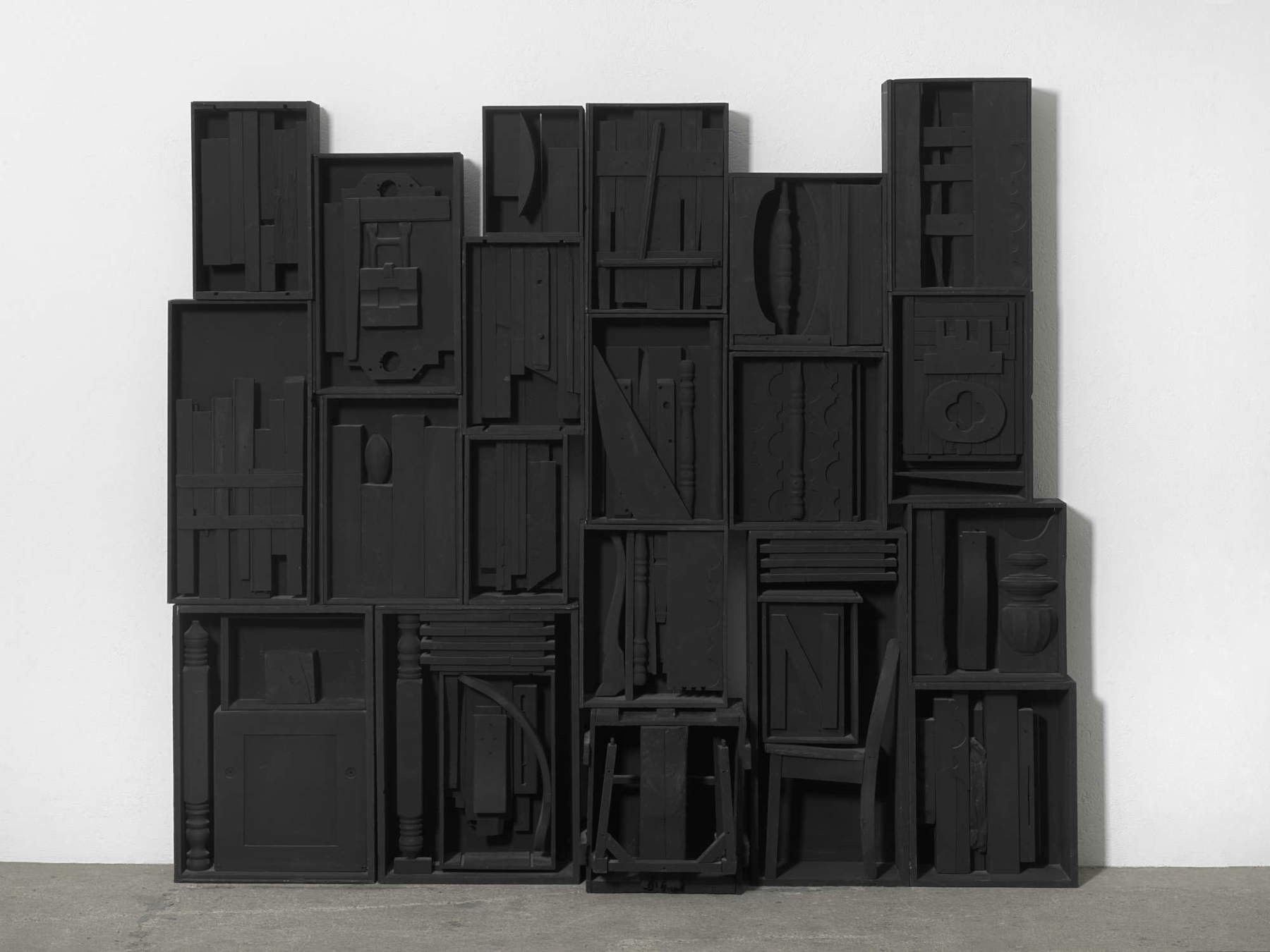

The Aeneas room presents different types of sculptures that are also wall-mounted but have flat volumes with no projecting elements because they are made from shelves used by printers, whose geometric, structured and rigorous lines refer to organized and well-ordered worlds where it seems there can be no injustice. The titles (such as Sky Totem, a self-supporting work from 1973 that stands next to them), refer to natural elements, landscapes and celestial spheres because, according to Nevelson, her artistic research cannot disregard the link with nature, a true hierophany. The Albani room, on the other hand, displays collages and assemblages in which, in addition to wood, the artist employs other materials such as metal, cardboard, newspapers, and aluminum film. These are intimate, transversal works, carried on from the 1930s until the end, which deeply connote the artist (she herself in her later years had become a “living collage” with her eccentric outfits, overlapping stoles, long false eyelashes and whimsical jewelry made from salvaged objects) so much so that she declared, “I don’t know if the definition of sculptor suits me: I make collages. I reconstitute the dismembered world into a new harmony.” These material combinations of Picassian and Schwitterian memory are influenced by the historical avant-gardes (Dada above all). Around the 1940s, she frequents several protagonists of the European avant-garde who fled to America following the outbreak of war, such as Duchamp, who in 1943 included her in a group exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery. She is fascinated by Surrealism (“Surrealism was in the art I breathed”), but also by Neoplasticism and Metaphysics.

In the Cesi room are grouped together unpublished etchings from 1953 and silkscreens from 1975, which testify to an unquestionable mastery of graphic means along with a marked inventiveness (which we find in the drawings of the 1930s, where the importance of the relationship between body and space is emphasized, and of movement derived from Cubism and experimental dance experiences with Marta Graham). In the same room is a video interview with the artist along with photos of the famous Chapel of the Good Shepard in Manhattan: an environment she designed inside the modernist church of Saint Peter’s, entirely white, with immaculate sculptures (“I wanted to create an environment that evoked another place, a place of the mind, a place of the senses”). We are in that phase that will lead Nevelson to move from Nigredo toAlbedo (or Opera to white), ending in the Carracci room where the last stage of the alchemical process, called Rubedo, takes place. This room houses luminous golden precious works, almost metaphysical from the regal wooden elements, round, spherical and therefore closer to perfection (“Gold is a metal that reflects the great sun...and wood recovered in the street can be gold”). Gold is also a color that reminds the artist of ancient Russian and Jewish icons along with suggestions from trips made to South America.

Here the alchemical process is accomplished, the reunion of opposites, the union of spirit and matter, male and female in which, as the curator observes, “in order to reincorporate the female experience of history, the artist brings into sculpture what women, excluded from history, have preserved over the millennia: the magical, alchemical, primitive historical relationship with the real.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.