by Ilaria Baratta, published on 22/12/2018

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci's Leicester Codex' in Florence, Uffizi, from October 30, 2018 to January 20, 2019.

The return to Florence of the Leicester Codex by Leonardo da Vinci (Anchiano, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), thirty-six years after the 1982 Florentine exhibition that displayed the great genius’ precious manuscript folios, is not intended to be, as Uffizi Galleries director Eike Schmidt declares, "an ad hoc occasion to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death ", but rather a sharing with the public of the results of the studies and discoveries made over the past three decades, because “Leonardo, his art, and his writings are constantly evolving subject matter, and not a year, or month, goes by in which nothing new emerges about his work, the result of studies or discoveries.” An opportunity that, as Schmidt adds, was desired to provide for the new generations, who were unable to see either the aforementioned Florentine exhibition of 1982, set up in the Quartieri Monumentali of Palazzo Vecchio and curated by Carlo Pedretti, or the Bolognese exhibition of 1986 focused in particular on the Emilian outcomes and the Map of Imola, belonging to the English crown at Windsor. As in the case of the writer, who was not yet born in those years.

Having had the opportunity to admire in person one of the cornerstones of Leonardo’s treatises, such as the Codex Leicester, and to dwell closely on the different sheets, evidence not only of Leonardo’s infinite wisdom, but also of his writing and the small drawings with which he accompanied the text, arouses great emotion and a sort of veneration for the attitude with which the genius approached the great questions of nature. What we are confronted with could in fact be, as Alessandro Nova proposes in his essay in the exhibition catalog, a first stage of a universal cosmogony dedicated to the four Elements: the Codex Leicester focuses on the theme ofwater, then developing in the various fields of knowledge, such as hydraulics, geology, physics, cosmology, highlighting how the element influences them and how in certain cases it determines changes in our planet. An element therefore from which to start studying natural phenomena, as is underscored by the title of the exhibition set up in theMagliabechian Hall of the Uffizi until January 20, 2019, The Water Microscope of Nature. In a single room, the sheets of Leonardo’s famous manuscript are enclosed within display cases: the visitor will thus at first have an overview of the exhibition layout, along which he or she will wander to discover the different aspects presented in the extraordinary work. Also placed between the display cases are many technological stations that allow, through the Codescope, the visitor to make use of all the individual sheets and decipher their contents. This makes tangible to the public the extensive research work done on each individual sheet of the codex.

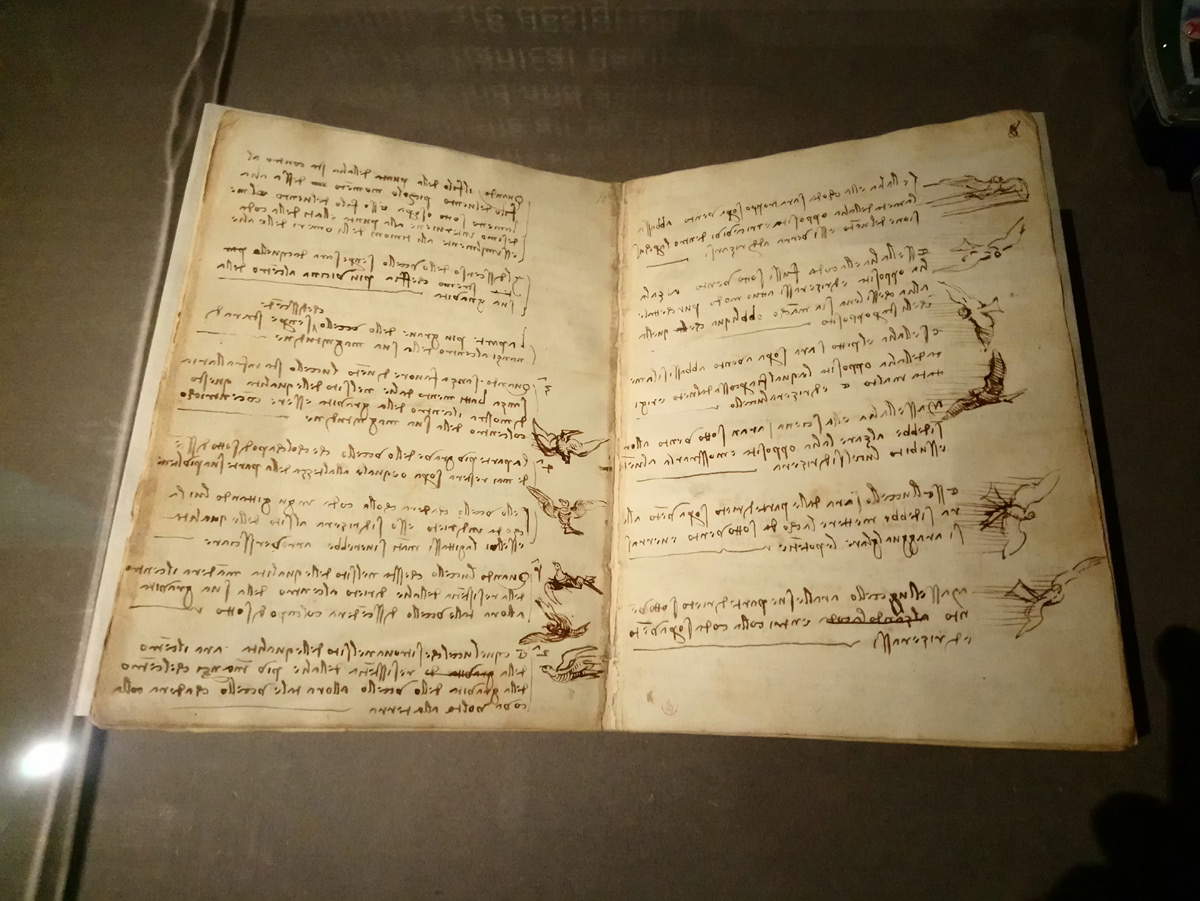

Declaring the three goals of the exhibition is the curator himself, Paolo Galluzzi: first of all, there was a desire to focus on the context in which the codex in question was written and illustrated with numerous sketches and drawings, the latter feature making the manuscript a unique document. Most of the codex was compiled in Florence during the years of Leonardo ’s second stay in the city, namely between 1501 and 1508, a time of intense cultural activity for Florence. And period in which, influenced by this cultural temperament, Leonardo devoted himself to fluid mechanics and the history of the Earth, arriving at the vision of a symmetry between the human body and the terrestrial body; he also studied the flight of birds and produced cartographic depictions that proved useful in designing and implementing interventions in the Tuscan territory, including the canal to make the Arno navigable from Florence to its mouth. There was also a desire to make the contents of the Leicester Codex usable and accessible to all visitors, even to those who do not have prior knowledge related to this topic: this was made possible thanks, as mentioned, to the Codescope digital technological tool that allows one to browse through all the sheets of the codex in very high resolution and learn about the themes of each one. A further and final goal was to highlight how Leonardo was ahead of his time, carrying out analyses and coming to conclusions that were imposed by the scientific revolution and that have become fundamental principles of modern natural sciences, such as the lumen cinereum of the Moon or the erosive character of water.

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. The Leicester Codex of Leonardo da Vinci |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. The Leicester Codex by Leonardo da Vinci |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. The Leicester Codex by Leonardo da Vinci |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex |

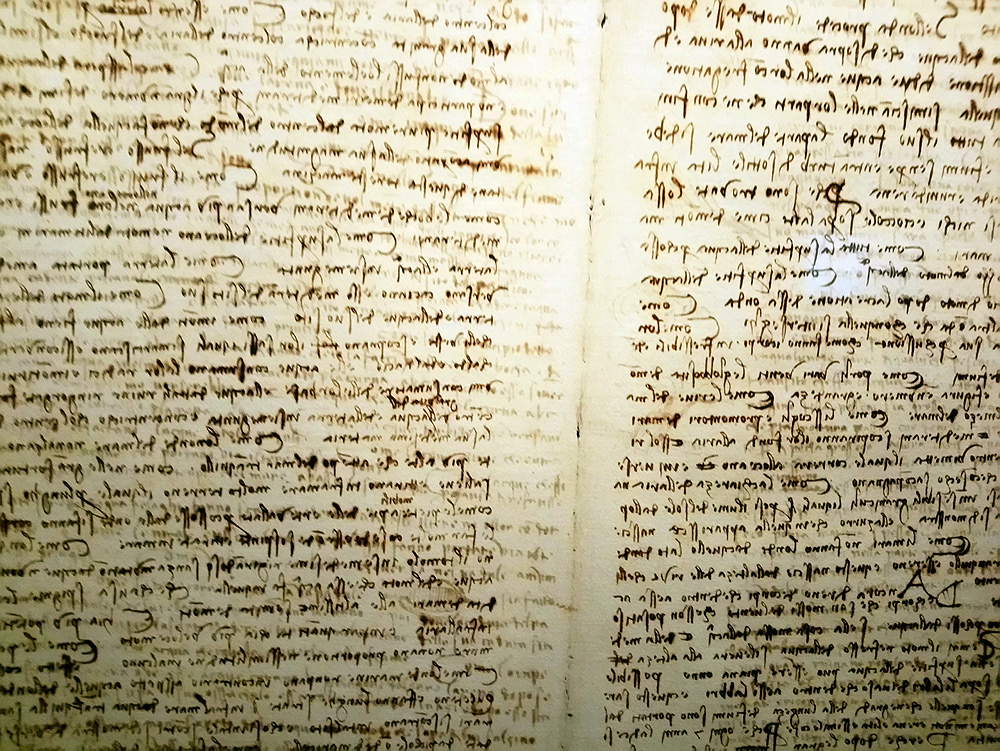

The Leicester Codex originally consisted of eighteen large sheets folded in half and inserted one inside the other to form an album of thirty-six sheets for a total number of seventy-two pages; on part of the sheets small, schematic drawings can be seen in the margins, and another peculiarity of the text is Leonardo’s handwriting, from right to left. Today the codex is sfascicolato and is shown, as in the exhibition, in loose sheets. Generally it seems that Leonardo wrote on all four sides of the sheets before inserting them one inside the other, and he usually started from what we would consider the last page to get to the first; in certain cases, however, he also proceeded in the other direction, turning over the set of sheets, which as mentioned were overlapped and folded to make a fascicle. And by this process he also produced the Leicester Codex. However, to speak of linearity with regard to the method followed by the genius is somewhat improper, since a single page could have been composed with materials added at different times or even the same page could deal with different topics or new pages could be inserted at any time. It is therefore difficult to arrive at a definitive order: the artist’s manuscripts always assumed a provisional nature. However, a new edition of the codex is currently being published in which scholars Domenico Laurenza and Martin Kemp have attempted to reconstruct the sequence of texts and drawings on each sheet. It has also been noted how some of the content of the pages has been transcribed or adapted from other manuscripts based on the presence of cross-references, or in particular there is frequent cross-reference to Book A, a text lost but reconstructed by Carlo Pedretti. In addition, the codex has the largest number, compared to the other manuscripts, of cases, i.e., questions that Leonardo asks himself, probably due to the complexity of the topics covered.

What provided considerable help in deciphering the order of the sheets were physical evidence such as ink penetration into the paper, stains, smudges, ink passed from one page to another, compass holes, and nib thickness, elements that led to the idea of compilation on separate sheets that were folded and then placed one inside the other.

Taking the entire file against the whole, a division betweeninner and outer series was considered: the former would include bifolios 8 to 18, while the latter would include bifolios 7 to 1; thematically, the two series could be said to be different: the inner one is mainly devoted to theobservation of moving water with a focus on hydraulic engineering, while the outer one is devoted to theoretical issues, such as the nature of the Earth’s body and the arrival of direct and reflected sunlight on the Earth and Moon, although, as mentioned, it is risky to generalize. Presumably, however, the inner series of eleven sheets was made uniformly in a single time period, while the outer series may be later and made piecemeal.

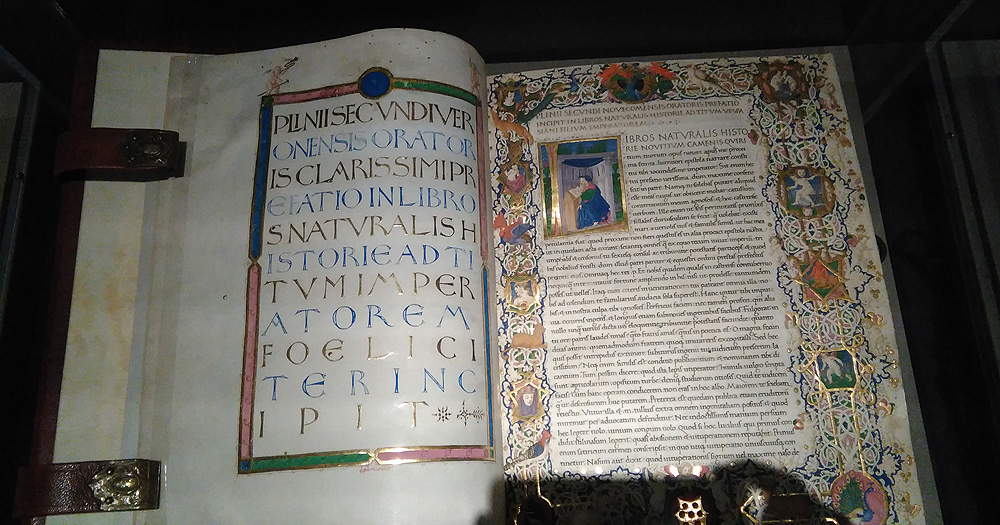

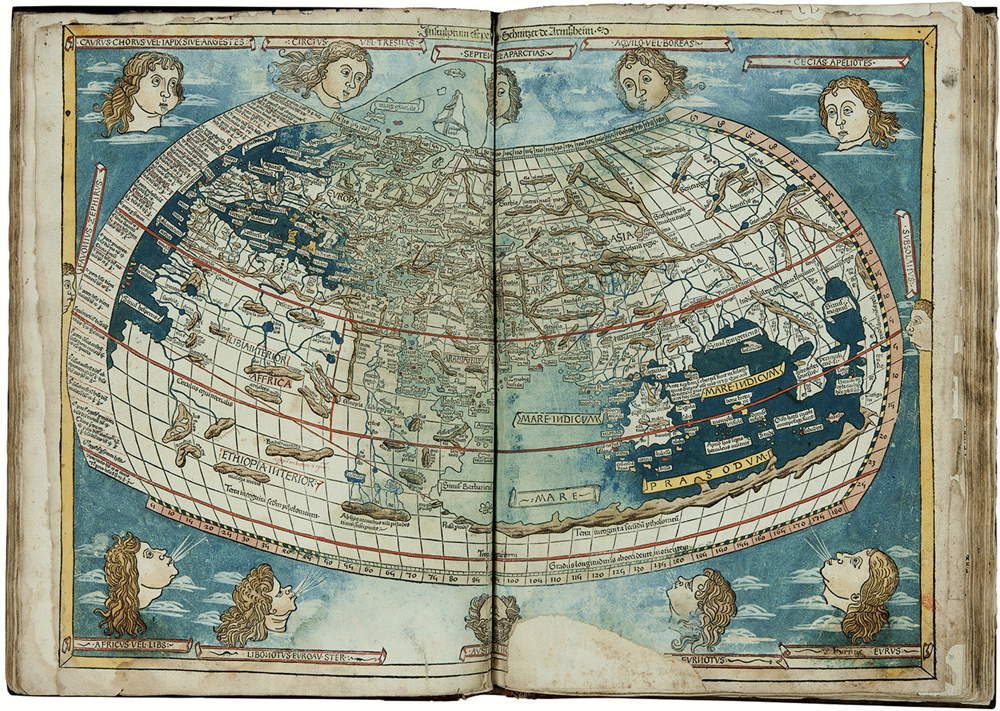

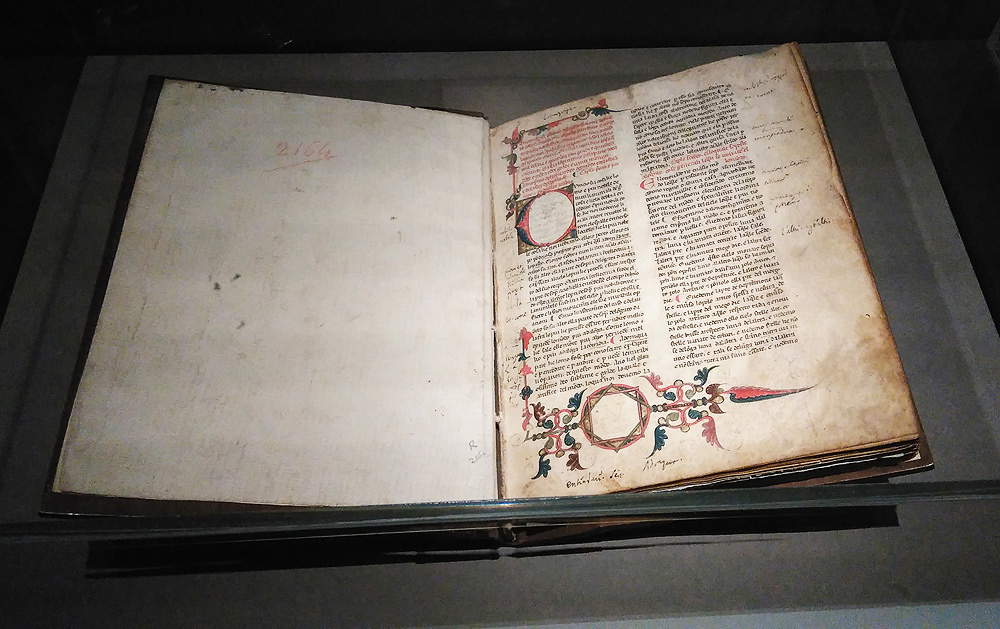

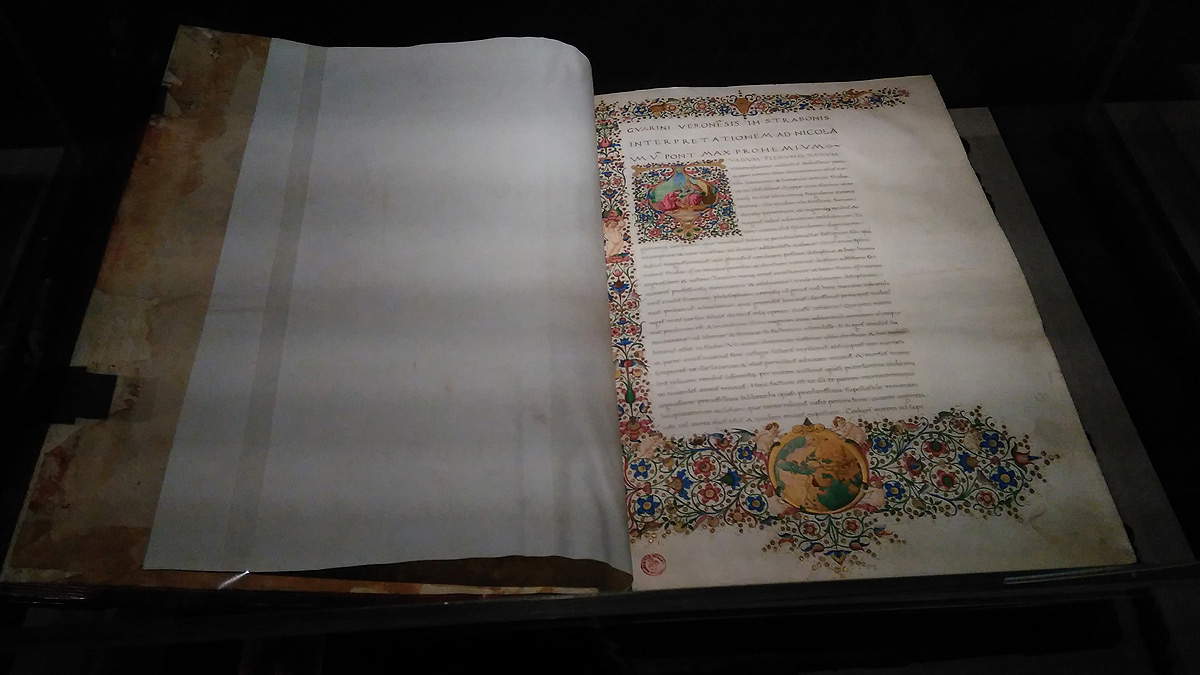

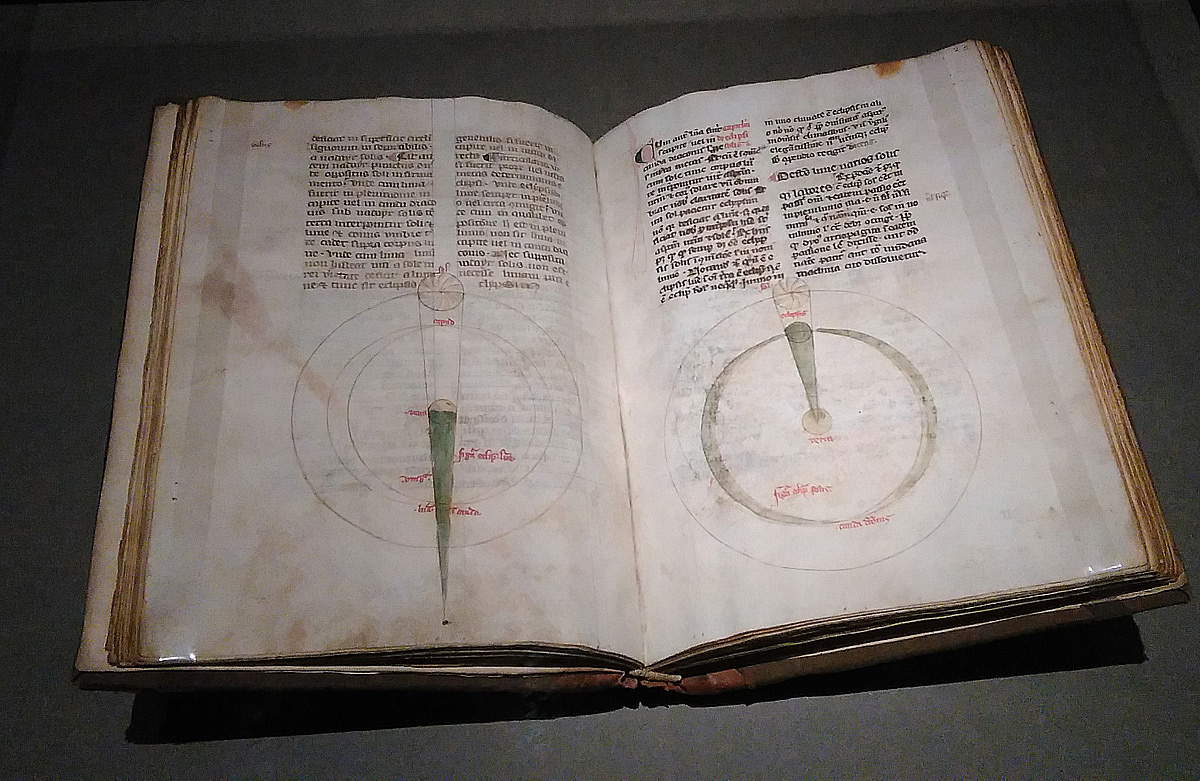

For the time in which it was produced, the Leicester Codex was highly innovative and original: no one had analyzed so painstakingly the very long-term processes responsible for the cyclical changes in the sphere of the elements, theincessant action of the elements. This is because “much more ancient are things than letters,” in the sense that the Earth’s macro-transformations take place over very long periods of time compared to the narrower timescales of written records. Therefore, the only tool for reconstructing these transformations isdirect observation of nature and subsequent interpretations based on rigorous mechanical reasoning. The Earth is in fact, according to Leonardo, a living organism undergoing cyclical transformations. However, Leonardo, in the years of making the Leicester Codex, possessed a rich personal library, so among the sources it is possible to mention Plato, Aristotle, Strabo, Archimedes, Ristoro d’Arezzo, and Dante Alighieri; in addition, he had acquired notions of natural philosophy, mechanics, optics, and cosmology in the course of his existence. The Florentine exhibition then opens with the texts that were in Leonardo’s library and that he used extensively for the Codex Leicester, including Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, Claudius Ptolemy’s Cosmographie , Jacopo Angeli ’s Latin translation of Ptolemy’s text, Strabo’s De Situ Orbis , Ristoro d’Arezzo’s The Composition of the World with its Cascions, and Giovanni Sacrobosco’s Tractatus de Sphaera . In Florence between 1505 and 1506 he had also composed the Codex on the Flight of Birds, where he had analyzed the maneuvers that birds perform to sustain themselves and move through the air by taking advantage of the wind. He had then designed man-bird wings, large articulated wings that humans could control by means of ropes, joints and pulleys so as to adapt them to weather conditions.

|

| Pliny the Elder, Ricciardo di Nanni (miniaturist), Naturalis Historia: ideal portrait of Pliny (1458; membranous manuscript, gyratory-white miniature, Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) |

|

| Claudio Tolomeo, Cosmographia: depiction of theecumene (1482; woodcut print on paper; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) |

|

| Claudio Tolomeo, Cosmographia: depiction of theecumene (1466-1468; membranous manuscript, with translation by Jacopo Angeli; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) |

|

| Ristoro dArezzo, The composition of the world with its cascions (13th century; membranous manuscript; Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana) |

|

| Strabo, De situ orbis (15th-century illuminated membranous manuscript; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) |

|

| John Sacrobosco, Tractatus de Sphaera: diagrams on Sun-Earth-Moon relations (14th century; membranous manuscript; Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana) |

|

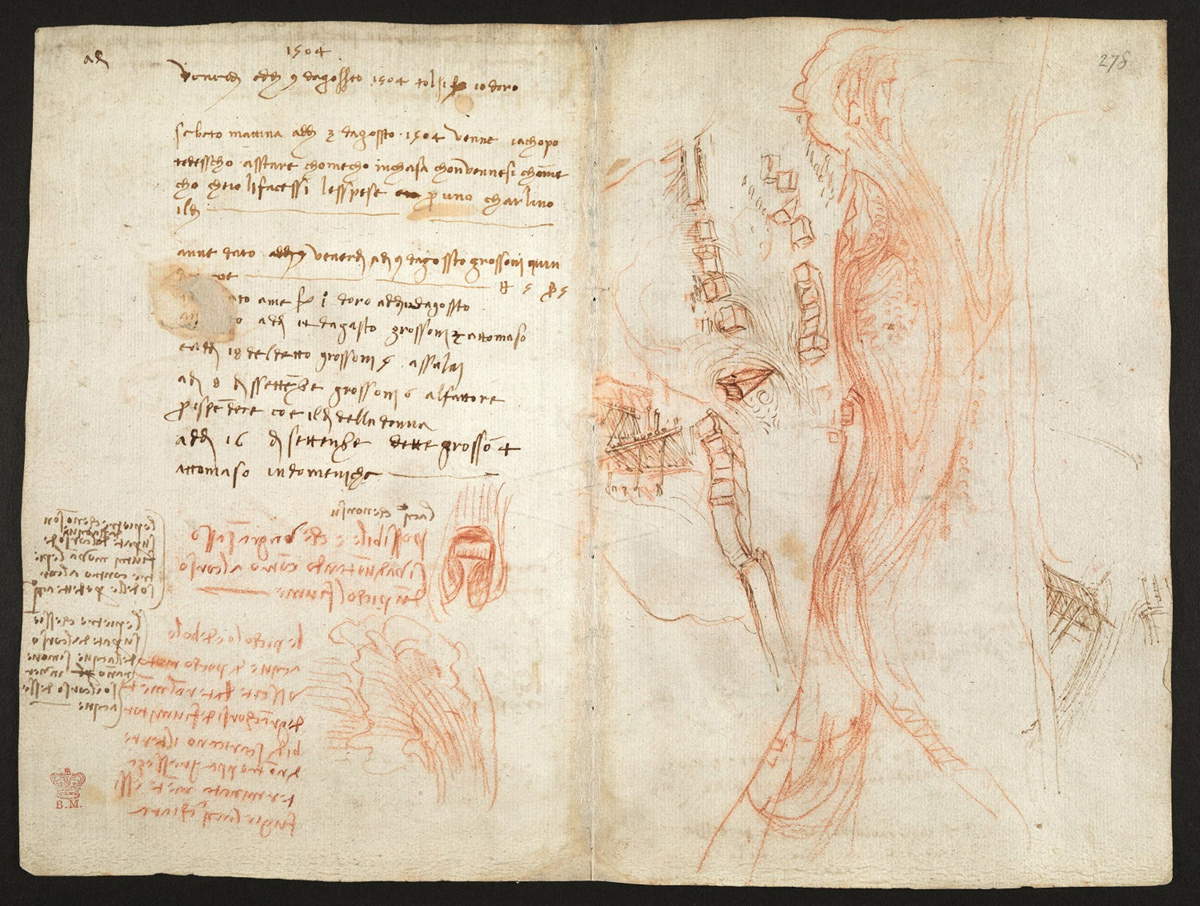

| Leonardo da Vinci, Codex on the Flight of Birds, folios 7v-8r (1505-1506; manuscript on paper; Turin, Biblioteca Reale) |

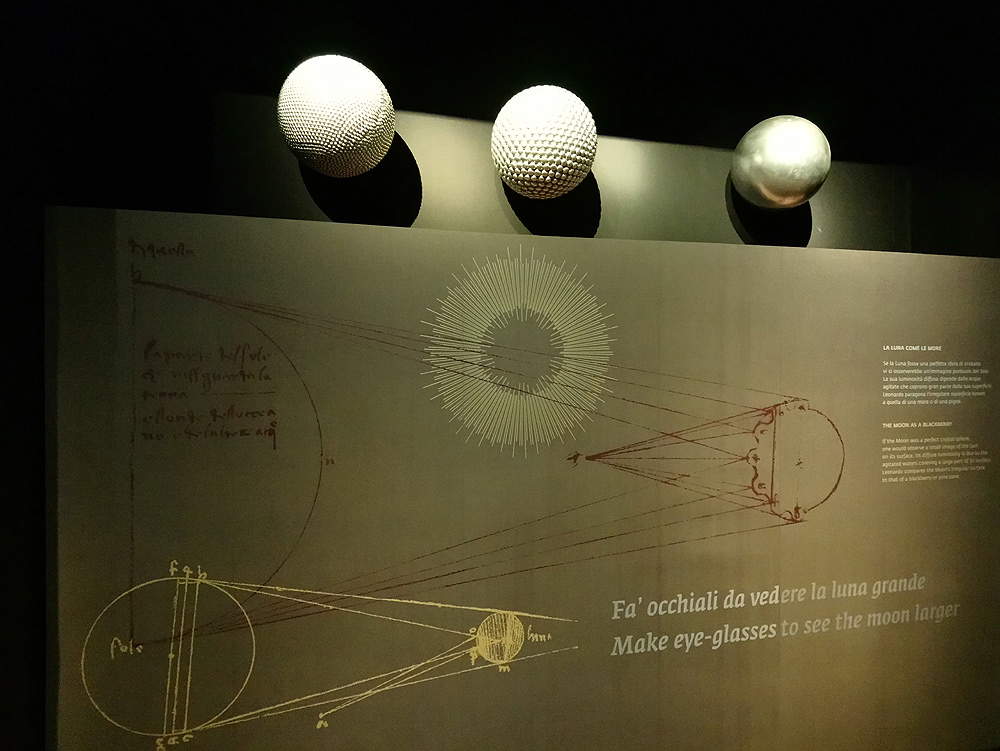

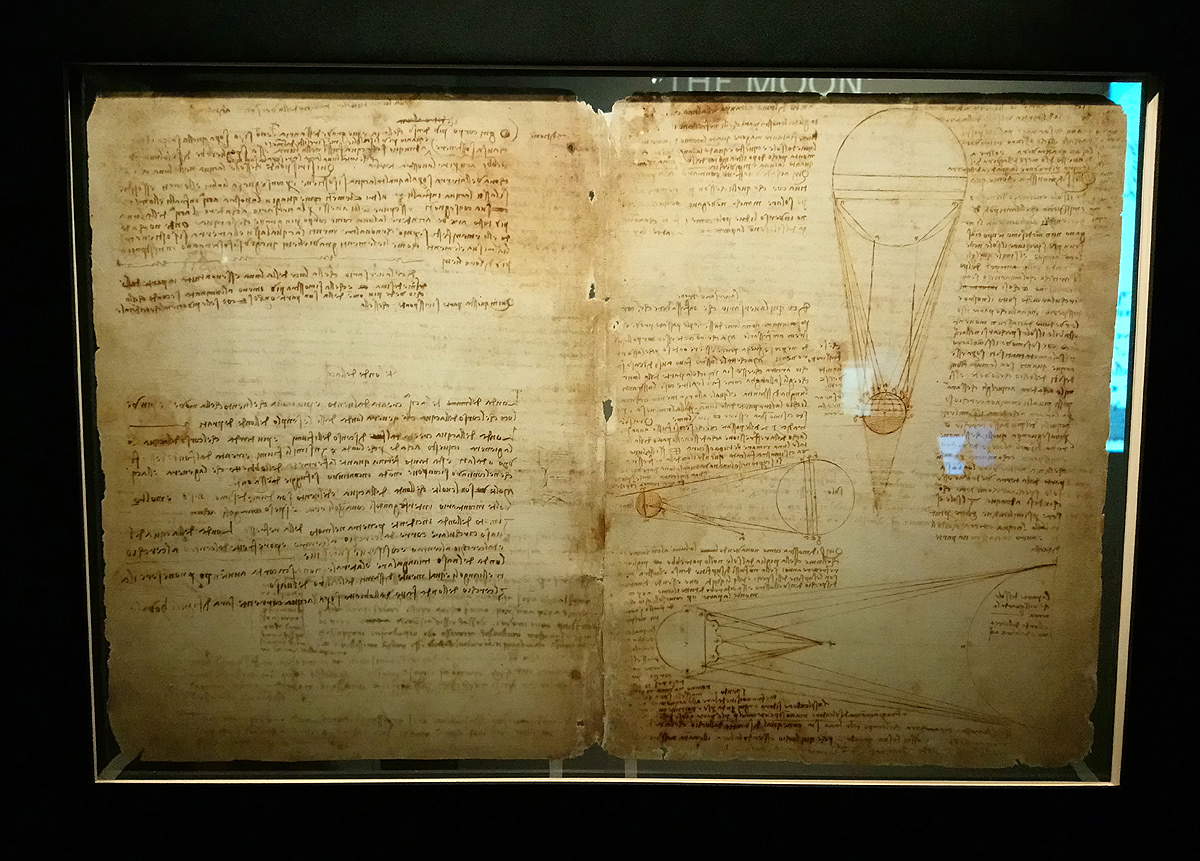

The first major theme of the Leicester Codex presented in the exhibition is the Moon as a second Earth: folio 36v, what for Leonardo must have been the first page of the codex, is devoted to the existence of seas on the Moon and waves in the water; the discussion of the Moon continues in the outer folios: in 1v he attributes the Moon’s irregular brightness to the presence of vast oceans on its surface, while in 1r he outlines relations between the Sun, Earth and Moon and studies the latter’s material composition, dwelling again on its irregular illumination caused by the rough waters on its surface, despite the fact that we now know of the nonexistence of seas on it, and compares the lunar surface to that of a blackberry or pine cone. However, it is in folio 2r that Leonardo asserts that the Moon is governed by the same laws as the Earth and provides an explanation for the phenomenon known today as ashen light. Rejecting the traditional cosmology according to which the Moon was endowed with light of its own, he states that it receives light from the Sun; its secondary light, or lumen cinereum derives from the sun’s rays reflected from the Earth’s oceans, which dimly illuminate the shadowed part of the Moon. In the back of paper 36 he discusses the great changes that the Earth has undergone over the centuries, starting with the observation of caves, and hypothesizes that subterranean collapses determined the origin of mountain formation, thus coming to explain the presence of fossils of marine animals on mountain tops.

As the title of the exhibition suggests, Leonardo was convinced that water was the key to understanding the organization and functioning of nature, in the most general sense. For this reason he began to study the motions of water, the way it affects other elements, and the changes it causes to the Earth, both externally and internally. The Leicester Code is therefore the result of his studies of everything about the water element, such as its structure, the swirling motions it generates, and the commonalities between air and water. These can be seen in practice through a whirlwind over the sea, which exhibits the same spiral motion as water: an interweaving of winds that lifts stones, sand and seaweed into the air along with vaporized water. The two elements, air and water, continually relate to each other in a reciprocal way: wind is generated by the evaporation of water, as are clouds that are a consequence of the evaporation of sea water that at high altitudes is condensed by the cold. Reciprocal changes occur mostly by heat or cold.

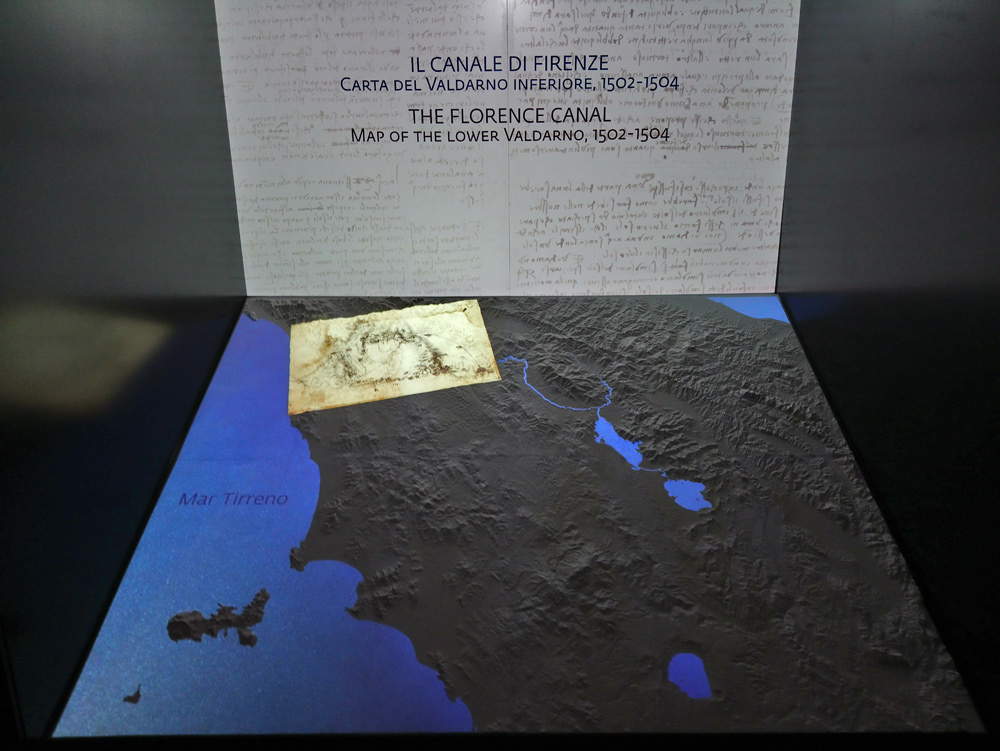

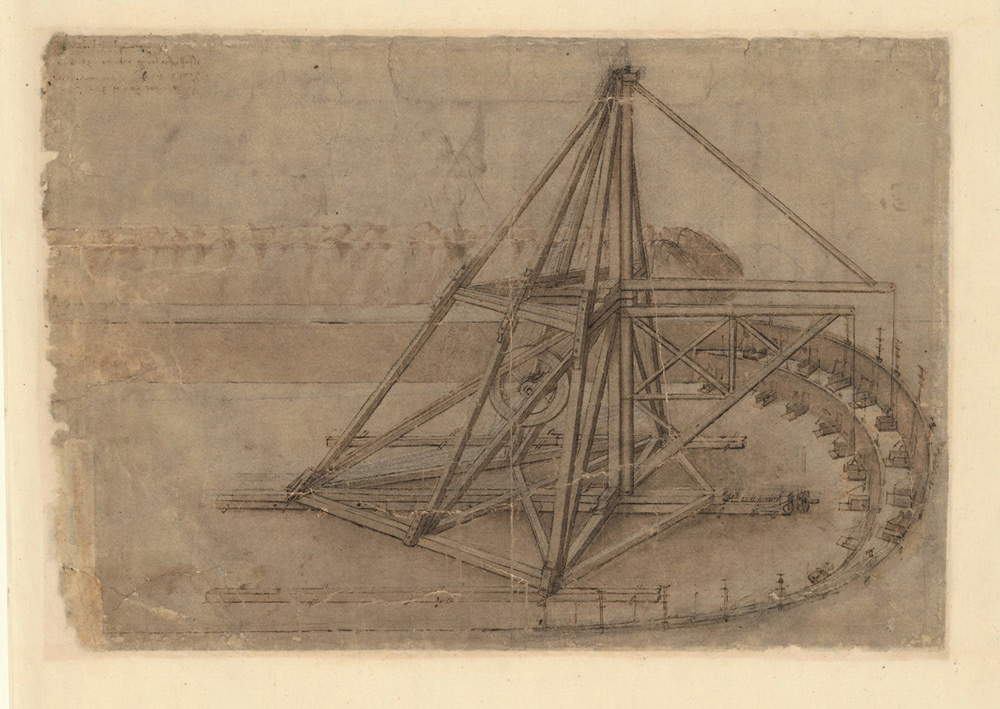

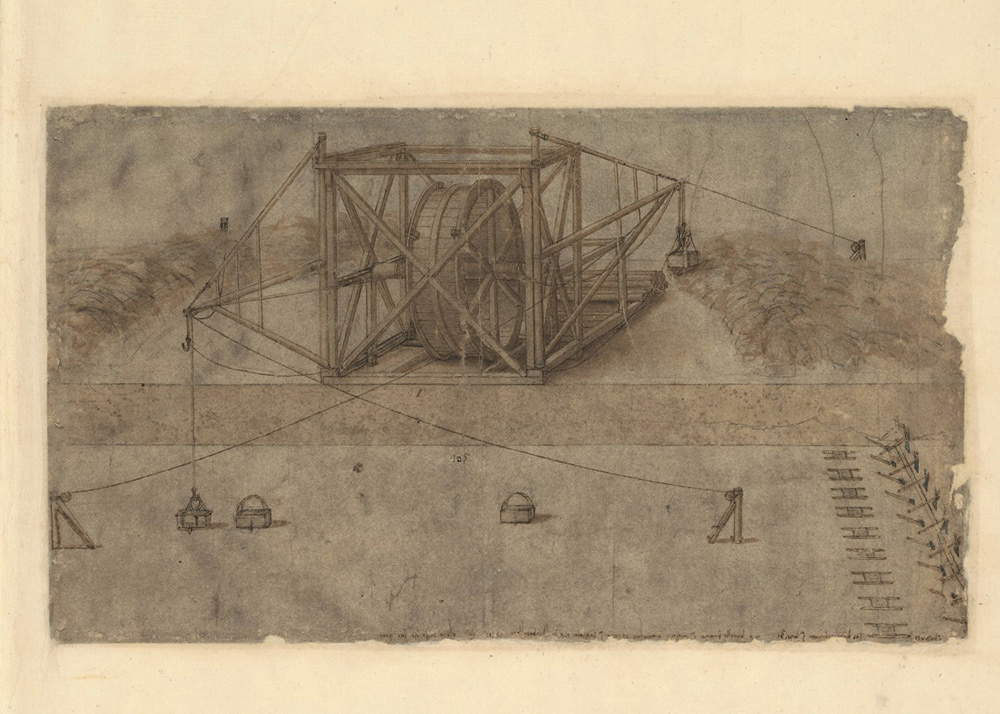

Innovative aspect for that era is the association between the swirling motions of water, air and blood flowing in the human being, expressions of the irrepressible force of nature: the idea of a symmetry between the flesh, bones, blood and the ground, rocks, waters. The body of the Earth is similar to the human body, as blood branches out in veins like water in rivers, an aspect well illustrated in the drawing in the margin of folio 3v. Sheet 17v contains themost detailed table of contents of the Treatise on Water (another table of contents is outlined on sheet 5r), which he would have liked to have completed, and among the topics analyzed he delves into the drop, that is, the elementary component of water, emphasizing its shape, cohesion with the rest of the water element, and elasticity by comparing it to the soap bubble. He also examines theorigin of springs on mountain tops, taking into account the theory that the Sun’s heat transforms water into vapor and causes it to rise until, having reached a higher altitude, it is reconverted into water by the cold; and again the formation of mountains themselves by the movement of land made by rivers from one hemisphere to the other, which causes the planet’s center of gravity to shift. Noting theerosion of water on land, he came to design dams that would resist the rushing flow of running waters and to study the effects caused by obstacles placed in the river beds: experiments with dams and pipes to put into practicehydrodynamics useful for the construction of canals and wells. According to his studiesî, it would be useful not to radically alter the course of a river, but to go along with it by gradually changing the direction. In particular, he takes into account the behavior of flowing water when it is obstructed by "obstructions,“ that is, natural or artificial barriers placed in the riverbed, which make a ”firm shield to the occurrence of the waters," as Leonardo himself reports: it makes deviations of its course, a useful process to avoid or diminish the erosion of riverbanks. According to his conclusions, as the banks widen or narrow, the speed with which the river water flows through its bed is changed, arriving at a constant flow. This principle, according to Leonardo, occurs in plant sap and blood circulation in humans. It is a study of hydrodynamics that he used to solve one of the concrete problems concerning the Earth and the course of rivers: flood prevention and flood protection. In order to dig canals, Leonardo designed semi-automatic machines and focused in particular on the channelization of the Arno upstream and downstream of Florence: there are studies and sanguine drawings and digital projections in the exhibition to make visitors understand the designs for such machines suitable for digging and removing excavated soil, already studied in the Codex Atlanticus, dating from 1502. It is mostly a kind of crane that, in addition to moving earth, moves on tracks and advances following the front of the excavation. The navigable channel of the Arno would have been fed by a system of canals to be built in the Valdichiana area, completing its reclamation. He thus began to depict the territory in cartographic drawings that take on the appearance of anatomical drawings: as previously mentioned, the waterways that descend from the mountains and reach the plains are likened to the blood flowing along the veins of the human body. The Valdichiana Map is a bird’s-eye view with elevation representations of towns, castles and mountain ranges. In order to raise awareness of Leonardo’s most significant projects to be applied to Tuscany’s main water basins, an animated model of Tuscany has been created with the waterworks planned by the genius.

|

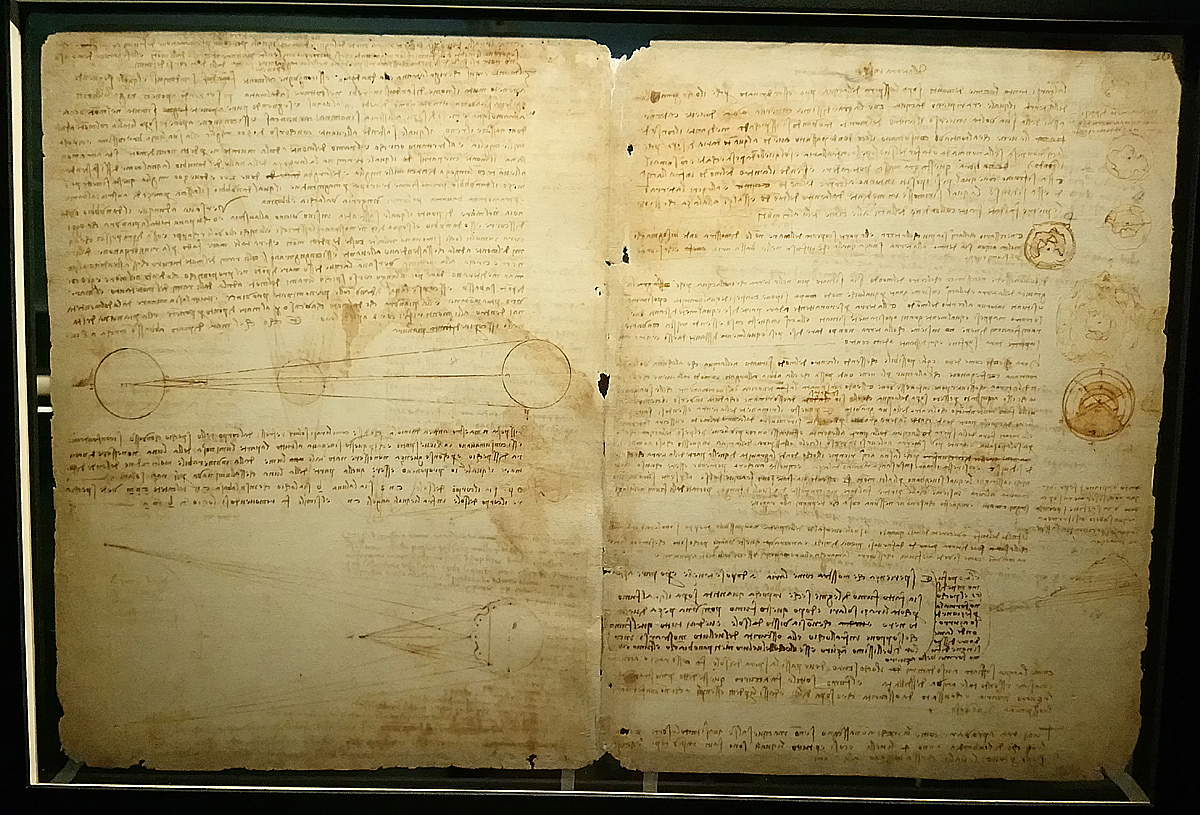

| Leonardo da Vinci, Leicester Codex, folios 1v-36r (1506-1510; manuscript on paper; Private collection). Courtesy Bill Gates |

|

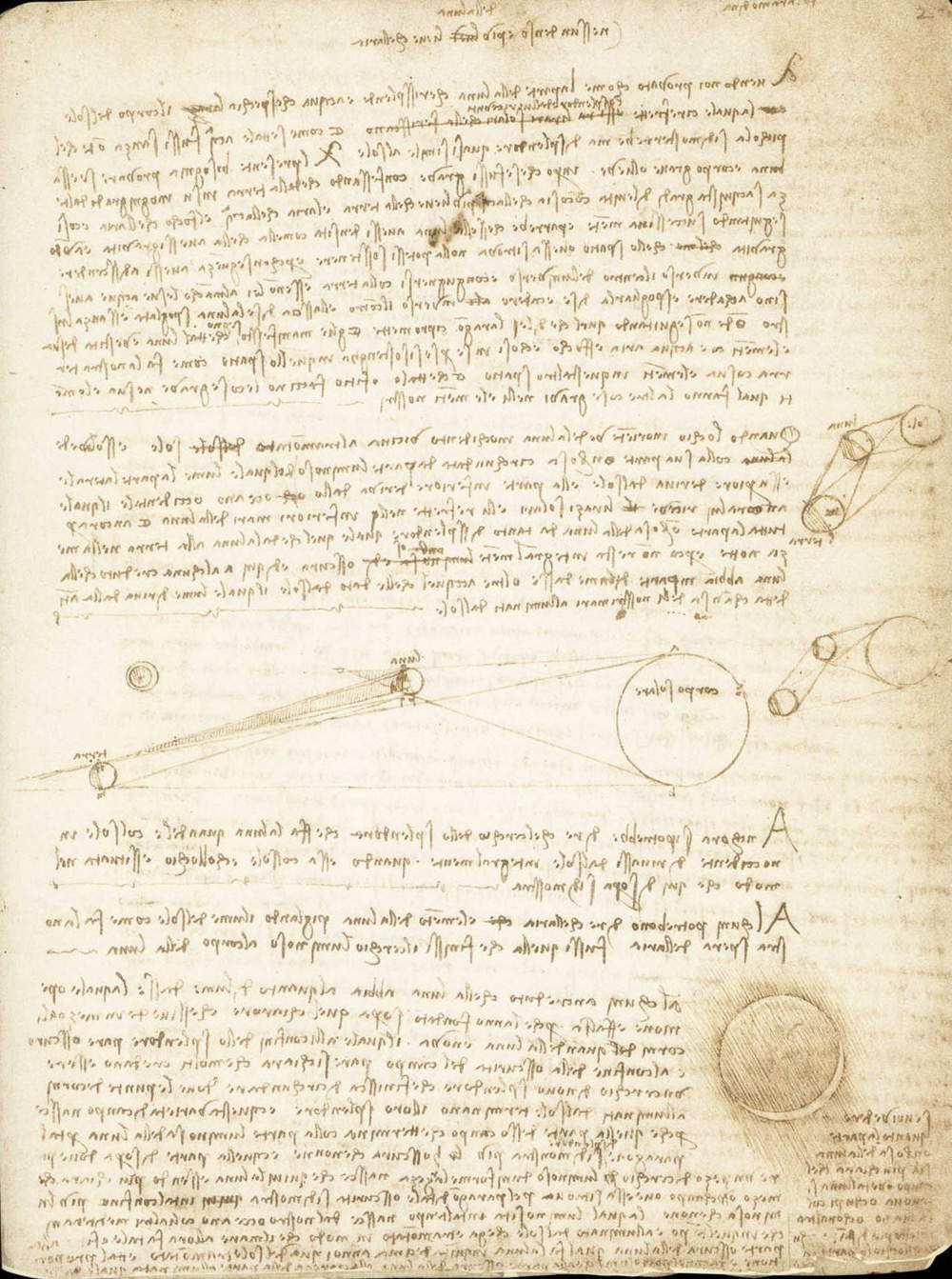

| Leonardo da Vinci, Leicester Codex, folio 2r (1506-1510; manuscript on paper; Private collection). Courtesy Bill Gates |

|

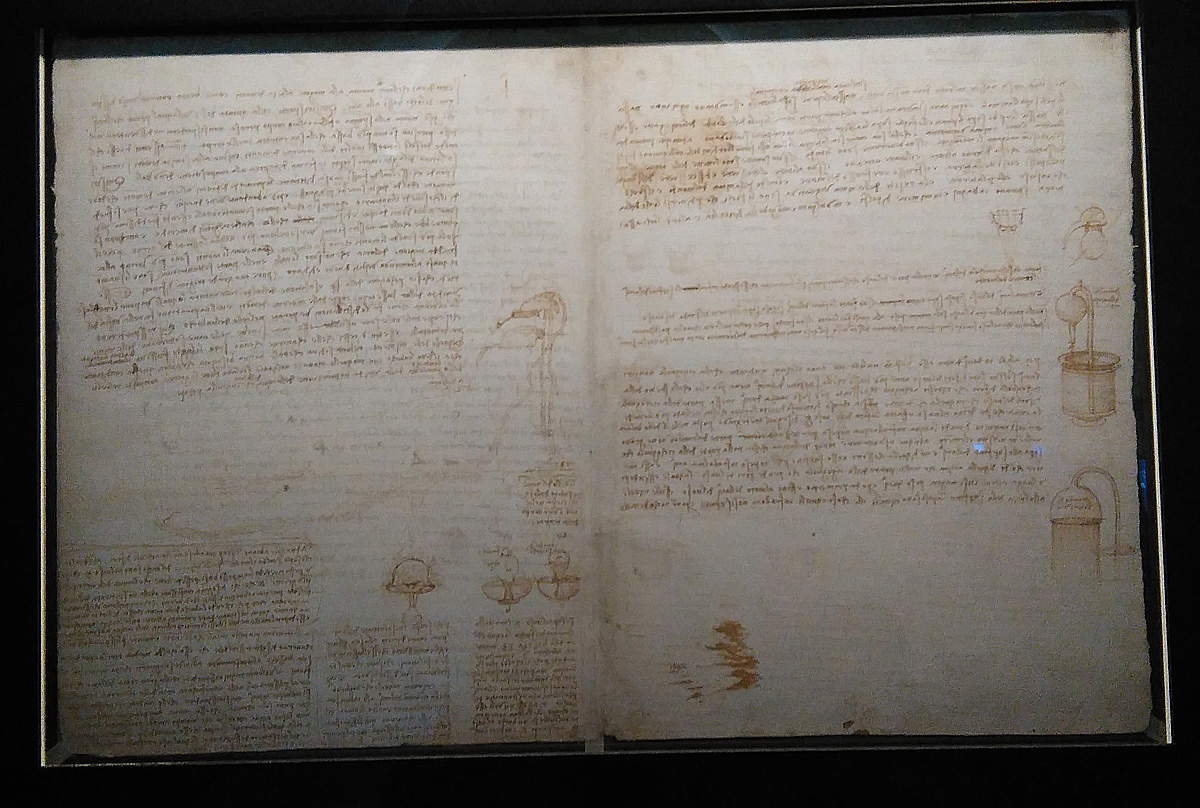

| Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Leicester, folios 3v-34r (1506-1510; manuscript on paper; Private collection). Courtesy Bill Gates |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Leicester, folios 17v-20r (1506-1510; manuscript on paper; Private collection). Courtesy Bill Gates |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Leicester, folios 36v-1r (1506-1510; manuscript on paper; Private collection). Courtesy Bill Gates |

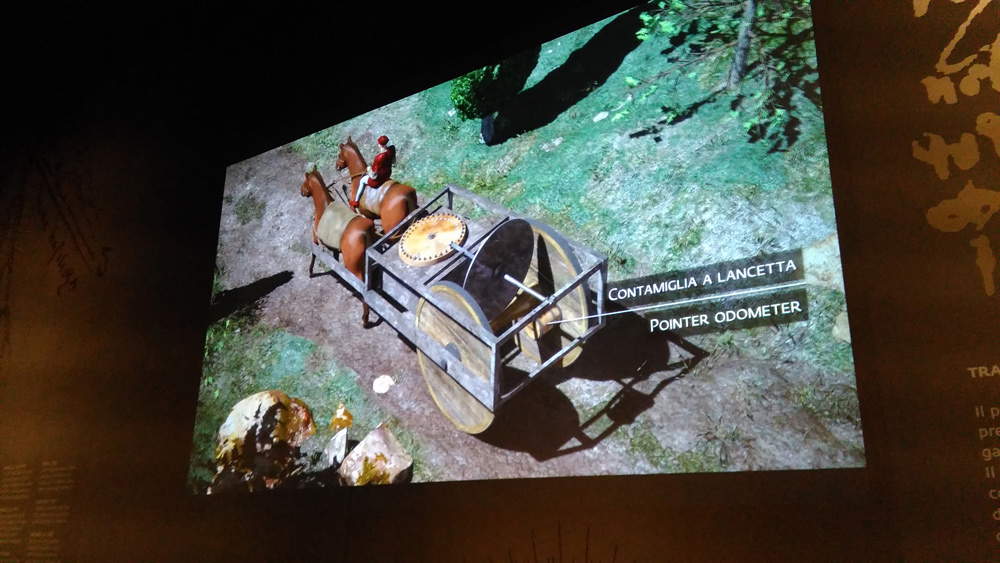

Among the most extraordinary inventions having to do with the channelization of the Arno is theodometer, forerunner of the odometer: an instrument that would have been used to measure the length of the canal. Exhibited in the exhibition is a model of such a machine: drawn by horses, it consisted of two wheels, like a wagon, which measured at each turn ten fathoms “from the ground” by driving a transverse toothed wheel with three hundred teeth; this made a complete turn every three thousand fathoms, that is, every mile. The cogwheel was in turn connected to a counter wheel that measured the distance traveled. In the codex he also proposes the first detailed description of the motion of waves and their impact on sea shores or river banks, particularly in folio 4v. He studies in detail the impact of the wave on the shore, noting how the crest collides with the next wave by splitting into two parts: one unfolds upward and then twists in on itself, the other plummets to the bottom dragging the lower part of the wave with which it collided out to sea.

Almost at the end of the exhibition, the European circulation of the Codex Leicester and its copies is outlined through a map: this was in fact the only manuscript by Leonardo to arouse great interest on the part of exponents of the natural sciences belonging to later generations. Between 1537 and 1717 the Codex Leicester was in Rome, at first in the hands of the sculptor Guglielmo della Porta and later in the hands of the painter Giuseppe Ghezzi. In 1717 the future Earl of Leicester, Thomas Coke, purchased the codex and had a copy made in Florence, from which others were made; in the second half of the eighteenth century a copy of the manuscript is attested in Naples, while according to the testimony of Giacomo Leopardi in 1813 a copy is found in Florence. Five years later, thanks to Goethe, a copy of the Leicester Codex was acquired by the Grand Ducal Library in Weimar. Also on display in the exhibition is a manuscript containing two copies of the codex, made in Florence in 1767. The original codex is acquired in 1980 by Armand Hammer, who gives it his name. It was then Bill Gates who reassigned it its first name in 1994, when he became its owner.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for Channeling the Arno, Arundel Codex, folios 271v-278r (c. 1504; red pencil, pen and ink; London, British Library) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study of Elevating Machines and Excavating Plants, Codex Atlanticus, folio 3r (1502 (?); pencil, pen and watercolor on paper; Milan, Veneranda Biblioteca e Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study of elevating machines and excavation equipment, Codex Atlanticus, folio 4r (1502 (?); pencil, pen and watercolor on paper; Milan, Veneranda Biblioteca and Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| The odometer model |

|

| Illustrative video explaining the operation of the odometer |

The review concludes by highlighting how the main themes of the Leicester Codex were presented by Leonardo himself in some of his paintings: the processes of sedimentation from which the rock formations that rise upward derive are depicted in the Virgin of the Rocks; the ashen light of the moon is made explicit in the secondary luminosity of Ginevra de’ Benci ’s face and in the St. Anne, the Virgin and Child with the Lamb. Geological theories about mountains and lakes are visible in the landscape that forms the backdrop of the Mona Lisa, while the feet of Christ in the waters of the Jordan in the Baptism of Christ by Verrocchio (Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488) and Leonardo can be compared to objects. Rattles, small whirlpools, are visible around the feet.

The exhibition is accompanied by an extensive catalog that, in the words of the curator himself, “represents the most comprehensive and authoritative resource for bringing into mature focus the analyses and highly innovative ideas proposed by Leonardo in the Codex Leicester and for reconstructing the intellectual and material context in which he conceived it. ”Indeed, it should be emphasized that the exhibition catalog stands as a very valuable, timely and rich tool for understanding the themes addressed by Leonardo in the codex folios. The essays are entrusted to leading experts who have exhaustively explored all the topics covered in Leonardo’s manuscript: from the compilation and history of it to the idea of water as the “common center of the elements,” from the objectives to the hydrographic maps of Tuscany and the excavation of canals, from the lumen cinereum of the Moon to the history of the Earth as a living being that undergoes perennial cyclical transformations. An outstanding contribution to a great return to Italy.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.