It is sculpture, despite the fact that it is a video that conveys it, the language that characterizes Adrian Paci’s new, extensive project. No man is an island, the exhibition that marks the second installment of the series conceived by Cristiana Perrella for Jubilee 2025, has its visual, physical and semantic center in the large bell protagonist of The bell tolls upon the waves, a video/sound installation from 2024 that has never been presented in Italy and is now on stage until Sept. 21 in the monumental complex of Santo Spirito in Sassia. In addition, an actual sculpture dominates, a few dozen meters from the Sistine wards of the former hospital on the Lungotevere, the window gallery space on Via della Conciliazione in the Vatican. The work in this case is the body of the artist himself, reproduced through a cast, engaged in Home to go in 2001: it is the work that launched Paci-with his epic of wandering peoples, history and the present-on the international contemporary art scene.

After China’s Yan Pei-Ming, whose gaze on the prison population opened the Conciliazione 5 series, the project commissioned by the Vatican’s dicastery for Culture and Education for the current Holy Year proceeds with Adrian Paci. The artist born in Shkodra in 1969 now tackles the world of migration in his own way, before other authors, during 2025, will have to grapple with the terms “environment” and “poverty,” again under the critical guidance of the newly appointed director of the capital’s Macro Museum, Cristiana Perrella. The Roman art historian just ten years ago had brought the Albanian artist, permanently active in Milan since 1995, to the Maxxi in Rome with a powerful video installation, signed with compatriot Roland Sejko: A quattro mani was dedicated to the discovery of the letters of Italians in Albania, sent home between 1945 and 1946, but never reached their destination. Voices, stories and dramas pass from one side to the other of the Adriatic Sea, the sea that the 20,000 damned of the Vlora, with the communist regime in Tirana in agony, crossed in 2021 to disembark in the port of Bari and that Adrian Paci, on the other hand, flew over in 2022, the year of the election victory of Sali Berisha’s Democratic Party, with a scholarship in art and liturgy in his pocket at the Beato Angelico Institute in Milan.

However, it is independently of these youthful studies in religious art that Paci - performer, video maker, painter and sculptor, all-around intellectual, author of the engaging video about the Syrian woman Rasha, selected by Anna Mattirolo in 2017 for the group show at the Quirinale titled From Me to Us, the City Without Borders - was chosen for the Conciliazione 5 series. Rather, the decision would seem to be due to the free, we would say secular, way in which the artist has dealt over the years with the stories of migrants, a multitude dear to Pope Francis, making their ordeal a universal drama. “I don’t give myself a social task. For me the risk is to construct categories, within which the personal dimension is lost, which for me remains fundamental, both in the conception of the work and in its construction,” the author once said of Centro di permanenza temporanea (2007), with that handful of refugees waiting on the staircase of a plane that will never arrive.

A stranger to the fake and sly commitment of so much “artivism,” according to the felicitous neologism coined by Vincenzo Trione for his book on so-called engagé art , the Shkodra-based artist on June 11 inaugurated No man is an island at the Vatican. And on that occasion he told of his own baptism received in great secrecy and at the hands of his grandmother in the Albania that forbade religion. He also dwelt, Paci, on his own knowledge of the Bible and the Gospels thanks to paintings “by Titian, Piero della Francesca or Gruenewald that were found, as paintings, in my father’s books” (Ferdinand, also a painter, who died young when his son was a child). Then Paci stressed about his art that “the work never starts from a theme, but from encounters. The image is not a theme, but an experience.” Such was the case with the birth of that sort of via Crucis in the course of which the artist carried on his own shoulders the roof of a house, like Atlas holding up the world or the refugee Aeneas the father Anchises: with Home to go, Paci started a journey, his own and that of the subject he interpreted, which we now admire in the solid form of a plaster sculpture through a cast reminiscent of the timeless figures of the American George Segal. The 2001 work can be seen, 24 hours a day, until Sept. 21, on the road leading pilgrims and tourists to St. Peter’s: it’s just a pity we can’t enter the exhibition space in Conciliazione 5, without thus being able to walk around the figure of this poor Christ crushed by the weight of a roof made of tiles that nevertheless overshadows the shape of a pair of wings.

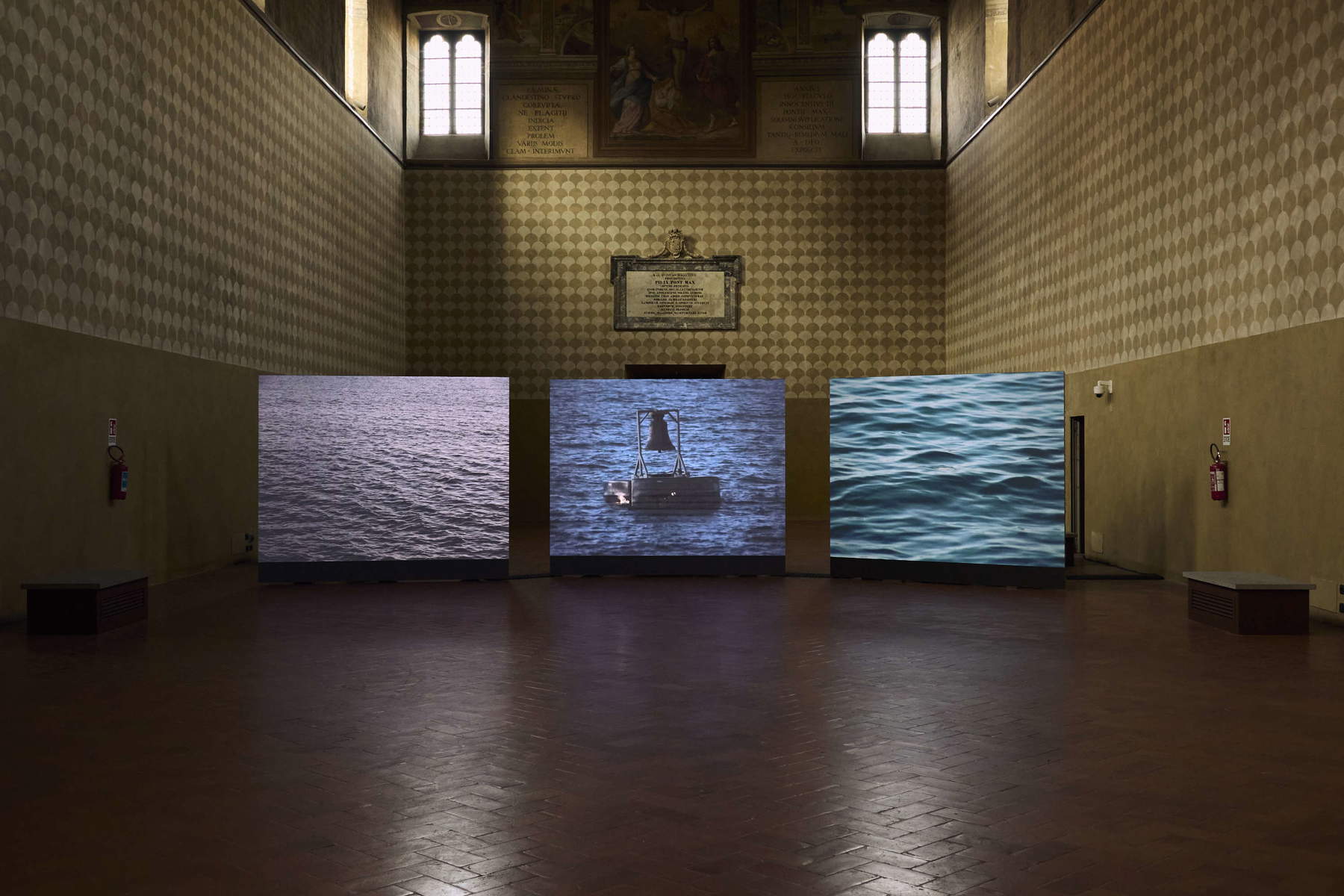

Sinking into history, also of art, is the other installation, the video installation of The bell tolls upon the waves - a quotation from John Donne’s Meditation XVII - proposed in Santo Spirito in Sassia (visit June 27 and 30 and on other pre-arranged days, from 3 to 7 p.m., until Sept. 21: the list on Conciliazione 5’s website and social channels). Produced by the Giorgio Pace Foundation and created a few dozen meters from the seashore in Termoli, the work consists of three screens, a triptych with the two side elements converging, like theatrical wings, toward the central one. The middle panel is itself in axis with, on the counterfacade, Jacopo Zucchi’s Mannerist fresco of the Crucifixion of Christ in the left aisle of the papal hospital, now run by the Asl Roma 1 and - strong of Bernini’s portal and, above all, Andrea Palladio’s ciborium - a museum of itself, open for several years to contemporary art (in 2024, for example, it hosted Piero Pizzi Cannella’s pictorial installation Le migranti). A new challenge, that of sixteenth-century religious architecture, for an author who has often confronted spaces of the sacred: from the church of Sant’Eustorgio in Milan in 2017 to the cloister of Sant’Agostino with the performance Chords last June 6.

In the approximately twenty minutes of footage in The bell, with the horizon line not always lining up on the three screens, we see a day at the seaside flow by: from sunrise to sunset to moonlit night. The center of the action where no living soul ever appears, but where humanity is continually evoked, is the bell hoisted on a buoy in the stretch of sea - legend has it - where in the sixteenth century the Turkish ship whose crew had stolen St. Catherine’s bell sank, causing the infidels’ hull to sink. The time of the church, as opposed to that of the merchant, lives again in Adrian Paci’s video in which it is the waves of the rough sea that shake the clapper and make the chimes ring. A powerful image, that of the Termoli bell-in Agnone Molise, the town known for the production of these instruments.

And if bells are found, as ready-made, in more than one of Jannis Kounellis’s installations, as well as in Luigi Mainolfi’s sculptural work, in Adrian Paci’s story constructed in moving images, the bronze giant marks among the waves the passing of the hours (sometimes even leaving the field to the framing of only the clouds in the sky), but also of the weather meteorologically understood. Above all, as Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonça pointed out, the work “is a warning and a warning sign about our loss of empathy and humanity towards migrants.” This is who (and why) Adrian Paci’s bell tolls for. His poignant, poetic, at times “painterly” view of the Adriatic is in fact also a political sculpture. Ready, without rhetoric, to be controversial.

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

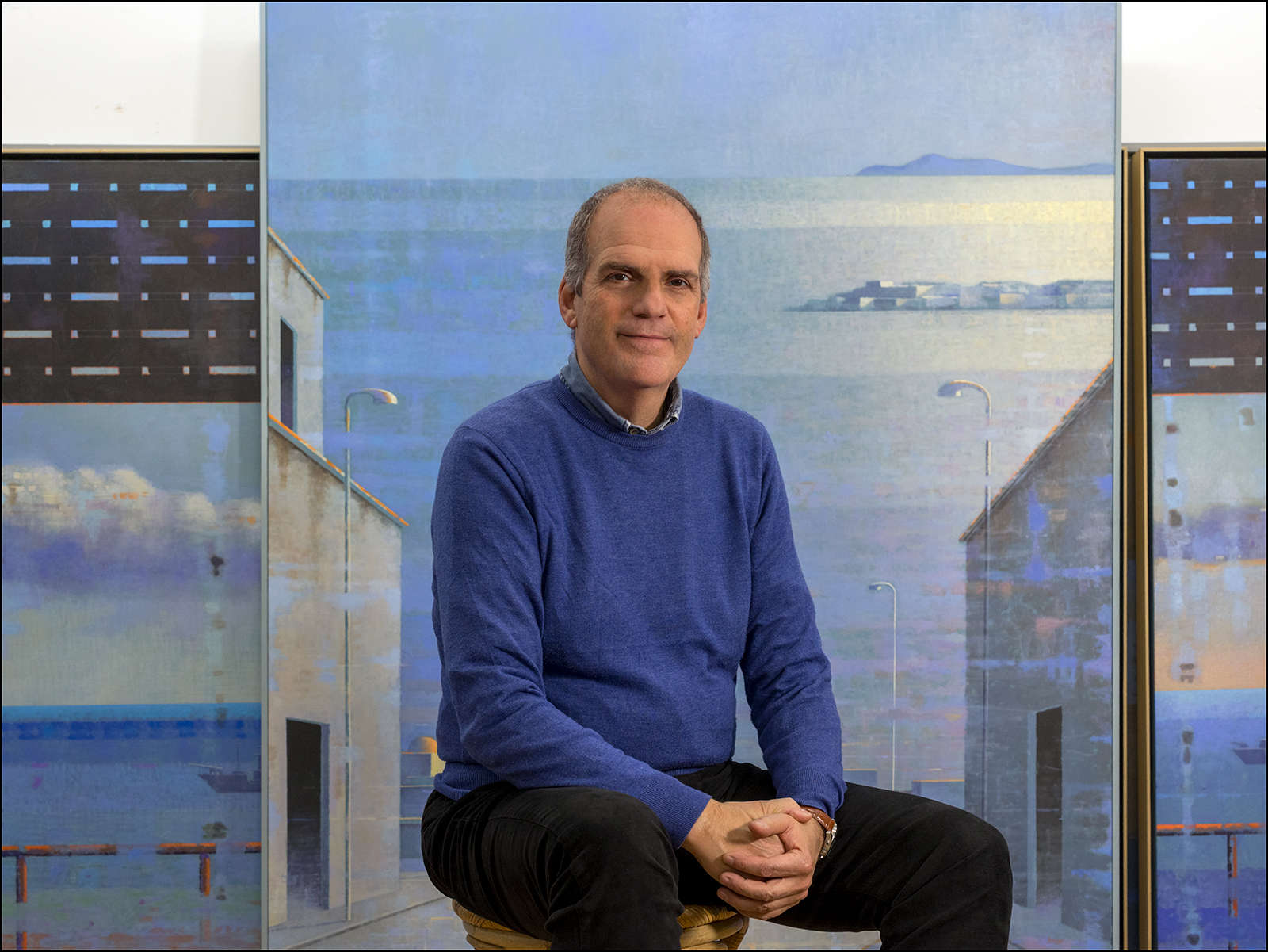

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.