The upcoming appointment with the 2026 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games in Milan and Cortina transforms the Trentino region into a stage where competitive competition is intertwined with a reflection on mountain culture. This is the context for the exhibition project entitled Winter in Art. Landscapes, Allegories and Everyday Life, an exhibition curated by conservators Dario De Cristofaro, Mirco Longhi and Roberto Pancheri hosted from Dec. 5, 2025 to March 15, 2026 by the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trento. The exhibition not only celebrates the sporting event, but also investigates its historical and social premises, analyzing how the confrontation with a hostile climate pushed humanity to devise technical solutions and forms of recreation that, over the centuries, have been codified in modern winter disciplines. Through a diachronic journey through the Middle Ages to the threshold of the nineteenth century, the exhibition highlights a selection of fifty works ranging from painting to sculpture, including graphics, porcelain and ceremonial sleds.

To understand the scope of the exhibition, one must look to the roots of European culture, where for centuries cold, snow, and ice have been interpreted exclusively through a negative and deadly lens. In classical and medieval literature, northern regions were described as remote boundaries of life, territories where winter’s stasis paralyzed all productive or war efforts. Virgil in the Georgics evoked a frost capable of imprisoning nature in a lifeless suspension, while Dante Alighieri placed the bottom of Hell in the Cocytus, a frozen lake understood as the point of maximum distance from the warmth and light of divinity. This anthropocentric view inextricably linked the seasonal cycle to the ages of man, identifying winter with old age, the final phase of existence marked by fragility and sterility.

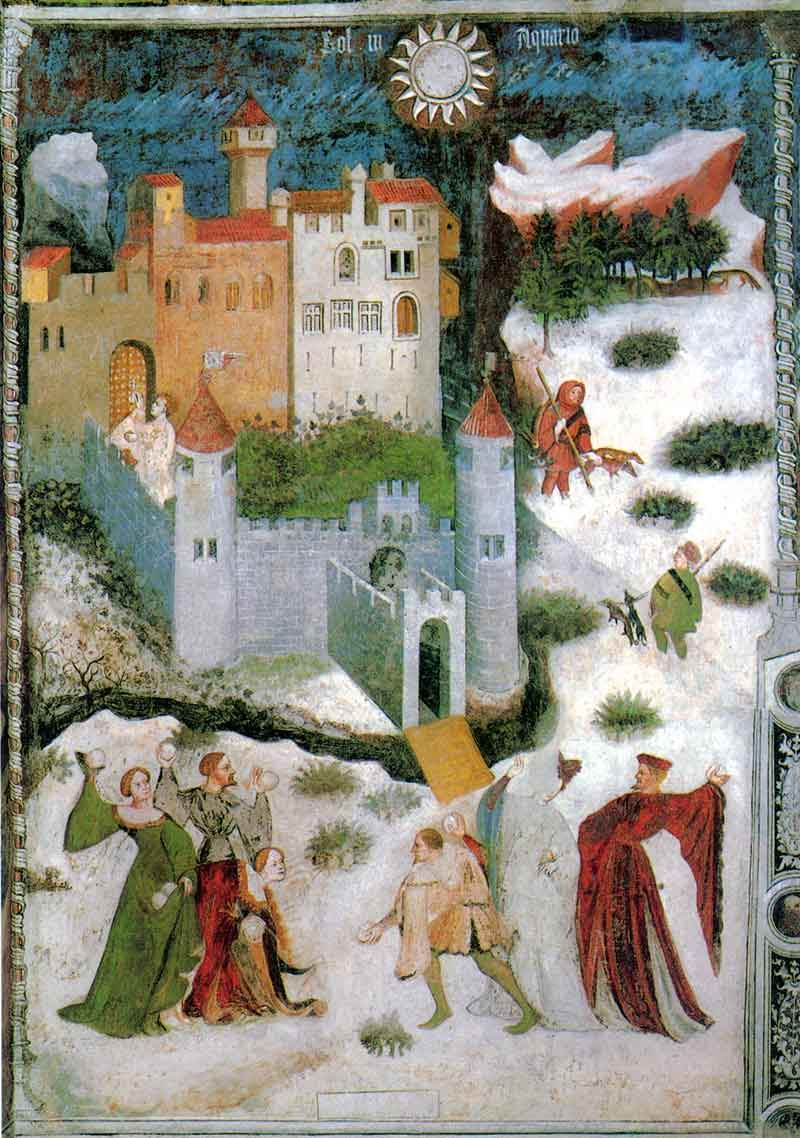

The shift in this symbolic paradigm finds one of its earliest and most glorious testimonies precisely in Trento, in the frescoes of Torre Aquila attributed to Master Wenceslas. The Month of January stands out as the earliest depiction of a verisimilitude snowy landscape in the entire history of European art. Here, the weather element is no longer just a threat, but becomes the scene of an unprecedented playful interaction: the famous snowball fight engaged in by a brigade of ladies and knights. Although the documentary accuracy of the manor house in the background, identified with Stenico Castle, contrasts with the players’ theatrical and ill-fitting attire for the cold temperatures, the work marks a fundamental shift toward a representation of winter that includes play and fun alongside the struggle for survival.

The investigation continues by analyzing the evolution of calendar cycles, tools that in the Middle Ages served not only to mark time but to inscribe human labor in a cosmic order guaranteed by divine will. If the earliest accounts, such as the Chronograph of 354, were limited to schematic personifications, over time the artists’ gaze widened to include material activities such as slaughtering pigs or gathering wood. Such labors, reinterpreted from a Christian perspective, ennobled peasant labor by transforming it into an instrument of redemption after the fall of Adam. Masters such as Jacopo Bassano and his industrious workshop took this genre to its highest expression, inserting into rural scenes religious and liturgical messages related to penance and advent, where the carrying of heavy bundles of branches became a symbolic reminder of the sacrifice of the cross.

In the 16th century, Flemish painting further revolutionized the perception of the frosty season, transforming the snowy landscape into an autonomous and modern subject. Pieter Bruegel the Younger’sAdoration of the Magi in the Snow, a special loan from the Correr Museum in Venice, shows humanity so immersed in the daily hardships of the climate that it appears almost distracted from the sacred event. In this context, the frozen surfaces of rivers are no longer obstacles to navigation, but are transformed into public spaces of sociability where skating and sledding are practiced. Artists such as Hendrick and Barent Avercamp or Jan Wildens succeed in capturing the crystalline atmospheres and twilight lights of the Dutch canals, offering a choral vision in which bourgeois, nobles and commoners share the same frozen scenery, helping to define the visual identity of a nation in the making.

Winter in art, however, is also a scene of ostentation and prestige for the European aristocracy, as documented by the section devoted to parade sleighs. These vehicles, authentic status symbols decorated with extraordinary technical mastery, served to demonstrate the rank of families during masked parades or gala pageants. The sleighs on display, which range from Dutch to Venetian and Tyrolean manufacture, feature cases carved in symbolic or mythological forms, often gilded and painted with noble coats of arms. A particularly fascinating example is the Venetian sleigh that recalls the lines of a gondola, decorated with the figure of a Moorish servant and the characteristic bow iron, probably used for celebrations at Carnival time. The spread of these luxury craft was favored by the climate of the “Little Ice Age,” which between the 15th and 19th centuries made the use of skates easier and more common than it is today.

The exhibition also touches on the more intimate dimension of heat preservation, analyzing the fundamental role of olla stoves in Alpine residences. Thanks to the recovery work led by the museum’s first director, Giuseppe Gerola, Castello del Buonconsiglio boasts an exceptional collection of these artifacts, which were able to transform a functional piece of furniture into an artistic surface covered with historiated majolica. Among the most valuable pieces are 18th-century turrets decorated with figures of emperors on horseback or allegories of the Virtues, such as the one from Sclemo in Banale, whose decorations derive from engravings by Antonio Tempesta. Also significant is the core of stoves from renowned craft centers such as Sfruz, in Val di Non, characterized by a more popular decoration that includes motifs of pomegranates and flowering saplings.

During the 18th century, the depiction of winter took on more lighthearted and gallant tones, influenced by French Rococo culture. Painters such as Watteau, Lancret, and Boucher transformed the cold weather into the sentimental romance of a couple courting during a sleigh ride or a lady letting her skates lace up in a snowy park. This evolution toward hedonism is also reflected in the applied arts, as in Meissen’s porcelain figurines depicting children engaged in snowball fights, images in which realism is combined with subtle allegorical meaning. In Italy, artists such as Marco Ricci and Francesco Fidanza specialized in snowy landscape painting, overcoming the rigidity of Baroque schemes to embrace an atmospheric sensibility capable of evoking ghostly lights and muffled silences.

In contrast, the Lombard school, represented by masters of the caliber of Pietro Bellotti, Antonio Cifrondi and Giacomo Ceruti, offers a more stark and direct vision of the cold season, linked to the reality of the lower classes and the fragility of the human condition. In these canvases, the line between the traditional allegory of the cold old man and the portrait of a poor commoner seeking warmth at a warmer becomes extremely thin. The emotional realism of these works allows us to perceive the harshness of a time when winter was not just an occasion for recreation, but a daily challenge for survival, charging the depiction with a deep existential afflatus that anticipates modern sensibilities.

The exhibition also focuses on eccentric and cultured figures such as Olao Magno, archbishop of Uppsala exiled to Italy, who through his Carta Marina and his publications illustrated for the first time to the Mediterranean public the customs and traditions of the northern peoples. Thanks to his presses installed in Rome, Magno disseminated images of warriors and hunters moving with agility on long wooden boards, skis, or crossing mountain passes using snowshoes similar to modern snowshoes. These depictions struck the imagination of artists such as Cesare Vecellio, who included the clothing of Nordic peoples in his repertories on world fashions, describing footwear capable of plowing through ice with incredible speed.

Winter in Art is thus a visual chronicle of a civilization that was able to converse with frost, transforming it from an insurmountable limit to an opportunity for creativity and technical ingenuity. The exhibition, complemented by a rich scholarly catalog and a program of in-depth talks with the curators, lectures and workshops for schools, is proposed as a key part of the Cultural Olympiad. Each work, from the monumental painting to the delicate porcelain cup, contributes to the narrative of that warm resilience of mountain peoples confidently awaiting the return of spring. Through the gaze of masters far away in time, winter is revealed no longer as the end of a life cycle, but as the candid and necessary precondition for any future rebirth.

The exhibition will remain open to the public at the Castello del Buonconsiglio until March 15, 2026, offering visitors the opportunity to rediscover the meaning of a season that has given European art some of its most poetic and original moments. Man’s challenge with the immaculate white of snowy peaks thus becomes a collective story of surpassing and beauty, capable of uniting past and present in the sign of universal Olympic values. In this journey between reality and imagination, winter ceases to be an enemy and becomes a cultural resource of inestimable value, a faithful mirror of the history and identity of the Alpine territory.

|

| Winter in art from the Middle Ages to Neoclassicism at the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trento, Italy |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.