Until January 21, you can visit an important exhibition on Francesco Hayez, organized in parallel with the major exhibition at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan. It is Hayez at Brera. The workshop of a painter, set up at the Sala Napoleonica of theBrera Academy, also in Milan. The exhibition, whose itinerary is divided into three sections, aims to investigate the artist’s method, thanks to several drawings (there are about eighty on display), three notebooks, paintings, prints and books. There is no shortage of comparisons with direct students, and there is also a reconstruction of the artist’s atelier. An interesting project, the result of long and serious research work, still in the making. To learn more about the exhibition, we interviewed the curator, art historian Francesca Valli.

|

| Hayez at Brera. A painter’s workshop |

Let’s try to frame the exhibition Hayez at Brera. A Painter’s Workshop: for Francesca Valli, curator of the exhibition, a premise is necessary...

A fundamental premise for me. This is not exactly an art-historical survey exhibition or not only. For the first time Brera is showcasing part of the legacy of an artist who, between exhibitions and school, spent 60 years of his life within the walls of the palazzo and to whose presence he owes much of his historical identity. So the problem (the responsibility also) was to evoke a physical presence through places (the reconstruction of Hayez’s studio in the Academy) and his system of work that was at the same time his method of teaching. Something similar, with differences, of course, has recently been done in Paris for the Picasso Museum where with the current exhibition a working set-up has also been reconstructed.

The point of the red damask drape that kicks off the exhibition at the Accademia is to evoke Hayez’s finest self-portrait, “Italian of Venice” in signature, that he kept in his Brera studio. And also a tribute of his second Milanese homeland to his Venetian-ness, if that fabric is the same as that of Doge Pesaro in Titian ’s altarpiece of the same name (a beloved painting). Nineteenth-century symbologies and metaphors that it was intended to indulge, as much as possible.

|

| Francesco Hayez, Study for Self-Portrait |

|

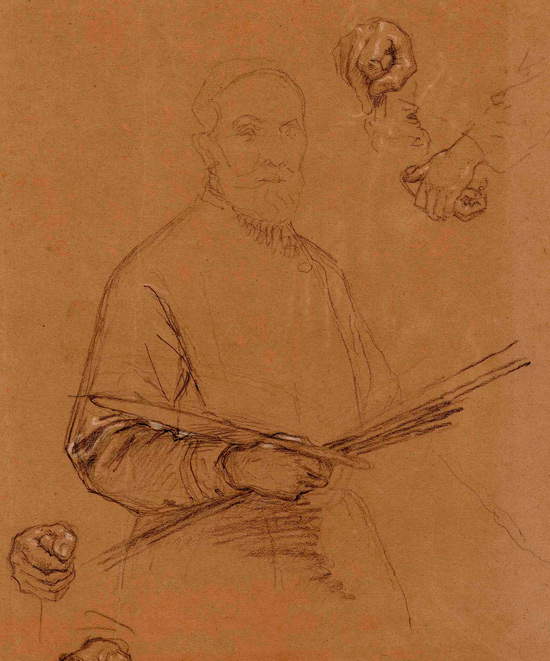

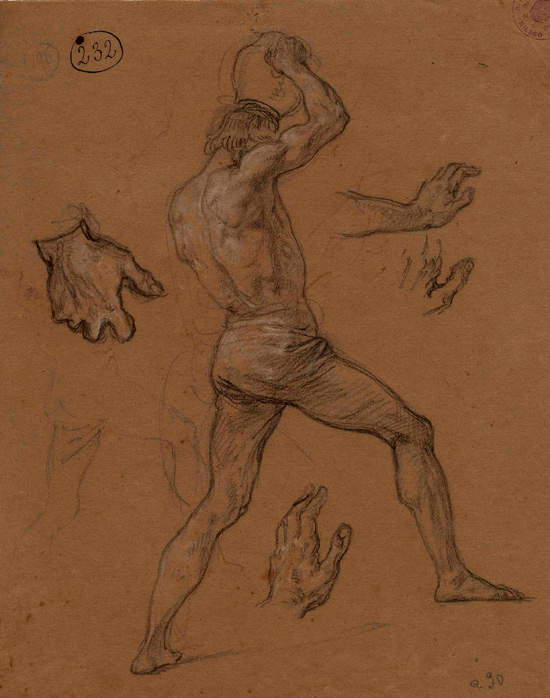

| Study for figure of Samson |

|

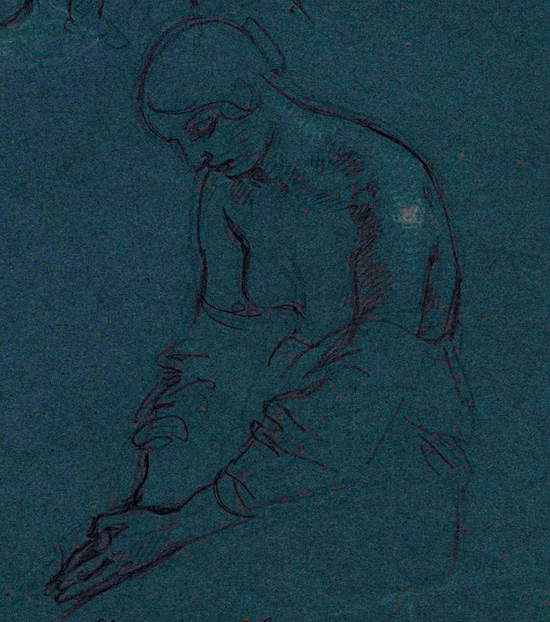

| Study for figure of Mary Stuart |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Canova’s La Maddalena |

|

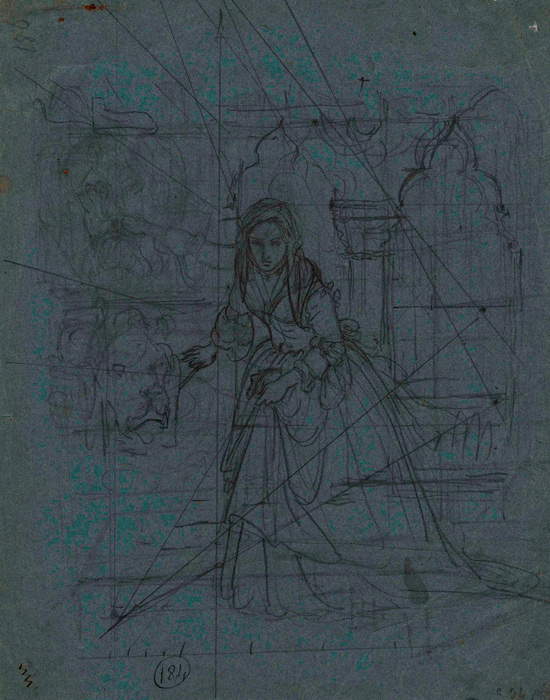

| Study for theSecret Accusation |

What are some of the most significant examples we can admire in the exhibition?

The Samson cycle, for the figure, which starts from the clenched fist gesture of Antonio Canova’s statue. The Thirst of the Crusaders cycle, for the Stories, some of the 80 preparatory drawings. But also the entire uninterrupted work on Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, a veritable primer on gestures. For the expressions, of which the Bolognese were famous, the connection with Guercino ’s painting Abraham Repudiates Agar, in the Pinacoteca di Brera, is interesting: relative toAlberico da Romano and the dismissed Foscari. Very beautiful are the working notebooks of Hayez’s youth, especially the red one, all dedicated to Mary Stuart. Interesting are the tools Hayez used to make portraits in death or at a distance: the one of Cavour, made with a funeral mask, the more famous one of Rossini with a carte de visite. Even the elder Hayez, suspicious of the genre, was convinced to use photography.

|

| Left, Study for character of Francesco Foscari destituito; right, Francesco Hayez, Detail from the painting Francesco Foscari destituito (1842-1844; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Study for the Silks of the Crusaders |

|

| Study for the Crusaders’ Thirst |

Unlike the major exhibition held at the Gallerie d’Italia, at the Brera Academy we also have the opportunity to see paintings by other artists, particularly Hayez’s pupils: how important was Hayez’s influence on painters in the Milanese (and non-Milanese) sphere? And which artists can we find in the exhibition?

We can find graphic translations of works by contemporary artists who were appreciated by Hayez: leading the way is Delaroche. Or by engravers, illustrators like Déveria. Or the famous etching by Luigi Sabatelli, who had preceded him to the chair of Painting, of the Plague of Florence. These works are all owned by the Academy, and we know through documents that Hayez himself had them bought, after his appointment as teacher, and that he kept them hanging in the classroom. On display are only the paintings of his official students, that is, starting more or less from his appointment to Painting in 1850, which are not very famous. In fact, the best-known names belong to an earlier phase, when after his arrival in Milan in 1822 he had taught on several occasions as assistant and substitute to Luigi Sabatelli. They are the Induno brothers, Eleuterio Pagliano, Giuseppe Bertini, Cherubino Cornienti and others not directly pupils, but attracted by the great success obtained by Hayez at the Expositions, over a period of time from the 1830s to the 1860s, when Hayez himself, in 1867, already an old man, decided to close with history painting, a genre that had become unfashionable.

The exhibition also features several engravings, which represent an important strand of Hayez’s production: just think of the fact that thanks to some of the engravings we are able to know about lost or untraceable paintings. How does the exhibition intend to enhance the printing techniques in Hayez’s production?

They are a sign of modernity, of the possibilities of dissemination of a new technique, lithography, which literally exploded, and of great quality, in Milan in the late 1920s, along with Italian translations of great European literature, from Walter Scott to Schiller. A great source of inspiration for masked balls, pantomimes, melodrama and, in our case, new subjects to paint. Hayez’s (he should have done those of The Betrothed, too) are beautiful. And so much did he believe in them that when he exhibited Mary Stuart being led to the torture in 1827, he placed his lithographic translation next to them.

|

| D’après Francesco Hayez, Alberico da Romano gives himself and his family as prisoners to the Marquis d’Este, watercolor |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.