What sense does it make today to talk about art criticism in a world where anyone can express an opinion but real debate is increasingly rare? In the age of the infosphere, social media and supposed cultural democratization, judgment seems to have taken the place of critical thinking, while the audience has turned into a large but often passive audience. In this scenario, can the role of the critic and curator still be that of the authority that imposes a canon or dictates a direction, or must it, if anything, become a space for mediation, listening, and shared construction of meaning? How has the figure of the critic changed in the era of the rise of the curator as interpreter of the present, with the crisis of cultural institutions and the impact of digital technologies on the perception of time and art? In this interview with Gabriele Landi, critic and curator Lorenzo Bruni, director of The Others Art Fair, discusses this in a conversation in which Bruni radically rethinks the functions of contemporary criticism. What emerges is a vision in which curating becomes situated practice, art an instrument of awareness and empathy a critical lever to inhabit, with responsibility, the complexity of the present.

GL. Lorenzo, what do you think is the role of the art critic today?

LB. This is a trap question, a kind of mystery box. To answer it one should first ask what we mean by “criticism” in the time of the hypothetical democratization of information. The question to be asked is: should the critic pass judgment on the work or propose a method of reading it? Question that carries with it: who has the right/duty to exercise this role? The question itself implies a value system that belongs to the last century, while today we live in a context in which cultural hierarchies, fortunately, have been dismantled-at least on the surface-by the horizontal access to information enabled by social and the digitization of the real. But this democratization, fueled (but not created) by new technologies, has produced a paradox: more opinions, less debate, more judgments. The moment everyone is an expert and everyone exercises intuitive criticism, no one listens anymore and everything becomes relative. So it is that in the absence of “shared” critical thinking, it is the market (instead of being a reflection of a system) that dictates what “works.”

... Are you talking about the crisis of criticism?

No, I am talking about the crisis of the role of the active audience. In fact, the “crisis of criticism” is a mantra that has been trotted out with every decade since World War II, often to avoid really redefining the role of the critic in relation to the changing needs of society and art itself. At best it has only polarized the issue between those who wanted a debate between specialists and experts and those who aimed, instead, at a popularization that would invest more layers of the civilian population. In fact, the figure of the critic - which evolved from Clement Greenberg to Harald Szeemann and Germano Celant, from Filippo Menna to Achille Bonito Oliva - gradually gave way in the 1990s to the curator. From Hans Ulrich Obrist to Francesco Bonami, from Hou Hanru to Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the curator became in that decade the privileged interpreter of new artistic urgencies in a global, hyper-communicative and post-ideological world. Her tool is no longer the text or the book but rather the thematic exhibition whose model, since 1992, seems to be embodied in the international case of Post-human (curated by gallerist and dealer Jeffrey Deitch) and then since 1997 in that of Cities on the Move (curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanru). That is, an exhibition that no longer has to present a single vision of art and for that reason allows artists who differ in nationality, cultural backgrounds, aesthetic ideologies and even generational backgrounds, but also in their use of different techniques, to coexist. The curator, after the early 2000s, is no longer a figure who has to gain acceptance, but rather is recognized as an indispensable cog in an international system precisely because audiences are expanding. This is how so many event opportunities arise in a short time: from new biennials in Asia and the Global South along with new museums. It is important to note that this variety of offerings has not been matched by real audience participation. However, an aspect of which we are only now becoming aware, and perhaps the cause was the excess of performativity in which the curator and the museum engaged in order to fulfill the market’s need to attract more and more audiences. Audiences that consequently had to be passive in order to turn into record numbers to wave around like a trophy with which to attract new funding.

Today do you think the figure of the curator is still influential?

Starting in 2012, in the new context of the sharing economy and internet 2.0, the figure of the curator/director must have appeared to the new generations to be too passive and now integrated into institutions and the market leading, slowly but surely, to the emergence of new figures such as content creators (not just influencers) who on social could reach everyone. In this context, the idea of re-founding the figure of the art critic appeared perhaps grotesque, just as it appeared impossible to re-think the figure of the journalist who was previously the one who dispensed information. The new generations of professionals in the world of journalism have responded to all this by founding new ways of investigating and with which to think about the mechanisms of how to read information so as not to suffer it passively given that, in the digital context, it is capillary and live. Thus, realities such as Will, Il Post, professionals such as Cecilia Sala, Francesco Costa or Daniele Raineri are born, andafter experiments such as Rivista studio and Lucy and other projects designed to take the reader away from the dictatorship of the algorithm. Similarly, the challenge facing the art critic now is not to invent and impose a canon, but also not to return to the chair, but rather to prepare a space that opens a real debate-not only at the level of fresh communication with which to attract the public-with which to create an antidote even, in the context of the infosphere, to informational apathy and the relativization of judgment.

In what direction are you moving?

In a definitely nonlinear direction, perhaps in a circle, looking for practices and people capable of activating alternative strategies, capable of generating shared systems of action from below, rather than theories imposed or to be imposed from above. I have always tried to adopt the role of an interpreter who does not judge from the outside, but from the inside. That is, working in direct contact with the artists themselves, a path already practiced in its time by Szeemann, Lucy Lippard, Celant, Pier Luigi Tazzi and many others. This is the spirit that has also guided me in these last five years at the artistic direction of The Others Art Fair in Turin.

Tell me about your experience as director of The Others.

The one with The Others is an experience that led me to confront the complex - and inevitably ambiguous - territory of the art market, trying not to suffer its logics, but to critically interrogate them. The starting point was to pose a simple but radical question to exhibitors who wanted to take part: what does it mean to be independent today? In a global system where everything is connected, where opinions multiply through social media, algorithms and increasingly horizontal channels, it is no longer enough to call oneself “other” to be truly alternative. Not least because the system - like it or not - we all inhabit it. That’s why The Others, since 2019 - the first year in which I am directing it - , has not only turned into a satellite or alternative fair, but into a platform of comparison, where historical galleries and emerging spaces, artist-run spaces, home galleries and nonprofit realities coexist without hierarchies, because there are no sections that differentiate them. What the public finds in the exhibition itinerary is a dialogue between similar themes and reflections, because what is presented is not the pedigree of the gallery but rather its coherent way of working by means of that project and those works conceived for the occasion. An aspect, the latter, enabled by the nomadic nature of the fair that always changing location and reactivating normally inaccessible spaces invites site-specific dialogue. Over the past few years, we have questioned ourselves a great deal with this modality with the various curators and curators on the Board to reflect on the role of cultural mediation in the time of the language of influencers and generalized opinionism.

How does this vision of yours of practicing participatory curating with both the galleries and the artists involved apply when you have to curate exhibitions?

By always trying to practice a purposeful exchange between bringing out the artist’s intention and its contextualization of meaning in a new critical system. It is by this mode that I intend and have always intended my role as curator-critic: builder of connections and contexts in which interpretation can emerge as a collective process. It is still a constant in my exhibitions today, which, however, distinguishes from the very beginning the first projects-from the Albania exhibition with Adrian Paci and Sislej Xhafa in 2001 at the Lanfranco Baldi Foundation (chaired by Pier Luigi Tazzi) to the collaboration begun in 2000 with the collective of the nonprofit space Base / Progetti per l’Arte in Florence-with which I tried to activate practices capable of questioning the authority of the curator and the very role of the exhibition. Consequently, the latter for me has never been a point of arrival to affirm a vision of art, but rather a point of departure. Therefore, my exhibitions, in addition to presenting the most interesting research at the time, have always focused on bringing out a possible new system of interpretation with which not only to predict future trends, but also to rediscover previously unseen aspects of past artists.

Can you bring me some examples?

The quest to make the role of the curator (to propose the interesting artist at that specific moment) coexist with that of the critic (to insert the work of an artist in a broader discourse that has to do with the history of art) must necessarily not be theorized but only practiced. This is what immediately jumps out if we look at the series of exhibitions I conceived and curated from 2005 to 2010 at the space of Via Nuova Arte Contemporanea in Florence involving artists of international standing from Martin Creed to Nedko Solakov, from Roman Ondak to Mai Thu-Perret, from Carsten Nicolai to Mark Manders, from Rossella Biscotti to Ian Kiaer, from Paolo Parisi to Dmitry Gutov, from Christian Jankowski to Koo Jeong-A. The individual collectives allowed for the emergence of different tensions related to the present (from the rapidly changing concept of landscape to that of the hero, from that of abstraction to the concept of the loss of collective memory) but framing it all within a broader common reflection, and that was to reflect on how to manage and how to deal with the sense of the legacy of modernism. Indeed, those were the years when the new digital archives and the long wave of post-ideolgic globalization led artists to reflect no longer on history with a capital S, but on the contribution made by the reactivation of memory. That memory to be rediscovered that could finally give substance to unprecedented perspectives with which to observe facts, but also give voice to those who until then had not had it because they had been absorbed in that of official channels. It is in this balance between immersion and distance, between complicity and analysis, between curatorship and theory that my research develops. It is a method that I have extended to more institutional projects as well, as was the case with the 2013 exhibition at the Klaipeda Art Center on the theme of travel or in the cycle of solo shows I have curated since 2018 at the Museo Novecento in Florence, under the direction of Sergio Risaliti, which led me to involve artists such as Ulla von Brandenburg, Jose Davila, Wang Yuyang and Mcarthur Binion .

So with your exhibitions and projects you have aimed to bring together a historical perspective with attention to the present. Is that the case?

Yes. I have tried to develop a curatorial approach that is both analytical and situated, capable of moving between structural observation and contextual intervention. This has led my work to decline on different planes: between local and global, between archive and chronicle, between institution and independence: in and out of museums, in festivals, in self-managed spaces, in educational contexts and on digital platforms. But what was most important to me was to try to move beyond the heroic idea of the curator as sole author, and instead take on a role of stitching together generations, languages, and submerged memories.

Would you define this need of yours to make new trends dialogue with history as a stylistic feature of yours?

The idea of reading the present also in a new and unprecedented historical key, I did not feel it to be my reading alone, otherwise it would not have been a critical tool. At that moment in history - the mid-2000s - there were already clear signs of an ongoing transformation: a shared demand from the public and artists for a new approach and a different way of understanding the relationship between art, society and history. The idea of history as we had known it in the twentieth century had been exhausted - the thesis elaborated in 1989 by the U.S. political scientist Francis Fukuyama found its most concrete declination in those very years - and it became necessary to identify new perspectives and practices capable of critically reinterpreting it. Such a situation became evident to everyone starting with Daniel Birnbaum’s Biennale in Venice in 2009. Thus it is that since the 2010s the reflection on modernism, memory and invisible genealogies has progressively redefined the curatorial field, to the point of transforming memory into a tool and medium of research rather than a theme. The problem came in later years as everyone started opening drawers regardless of the reason and making the activation of memory almost an aesthetic category rather than an ethical urgency. At the same time, a new trend emerged - starting in 2012 with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s documenta(13) - marked by an “archaeological” approach: no longer focused on the past, but able to auscultate the present in its layered complexity. On the other hand, it was as early as 2005 that art biennials were no longer only proposing themselves as places that must propose the trends of the present but try to re-present a new reading of the recent past, almost as if they had to impersonate an ideal contemporary museum. All the way to the extreme cases of Massimiliano Gioni’s Biennales, which included outsider artists, Christine Macel’s, which wanted to propose artists outside the market, or Cecilia Alemani’s, which valorized women artists who had long remained on the margins. In common they have the desire to question the canons of the dominant narrative while also proposing a reading that righted the wrongs of twentieth-century history. In parallel, other modes have focused on rethinking the role of the thematic exhibition, as was also the case with the 2016 Berlin Biennale on the post-internet and Manifesta in Zurich on the concept of work. Both events curated by artists, the former by the DIS art collective and the latter by Christian Jankowski. There would be many examples, however, and they all remind us that curating can no longer be an exercise of imposing authority. It must make itself a space of alliances, of confrontation, of questions. It must inhabit the interstices between artists, audiences, formats and languages.

What should a curator focus on today?

I think he should focus-as the new generations are actually feeling the need-to write good texts and to help the artist not only to create the conditions to best realize his work, but also to be able to freely express his thoughts about this rapidly changing world. It is a way that obviously leads to updating the concept of site-specific, central to the 1990s, with that of time-specific. It is the only possible reaction to the fact that we live in a time marked by algorithms and constant perceptual acceleration, what Claire Bishop has called the “presentism syndrome.” In this context it will become increasingly essential to think about exhibition formats that take into account not only place, but time: the time of process, of fruition, of exhibition, of context. It is a perspective that allows us to escape from the logic of the work as an isolated, self-referential gesture.

Time-specific works? Can you elaborate on that?

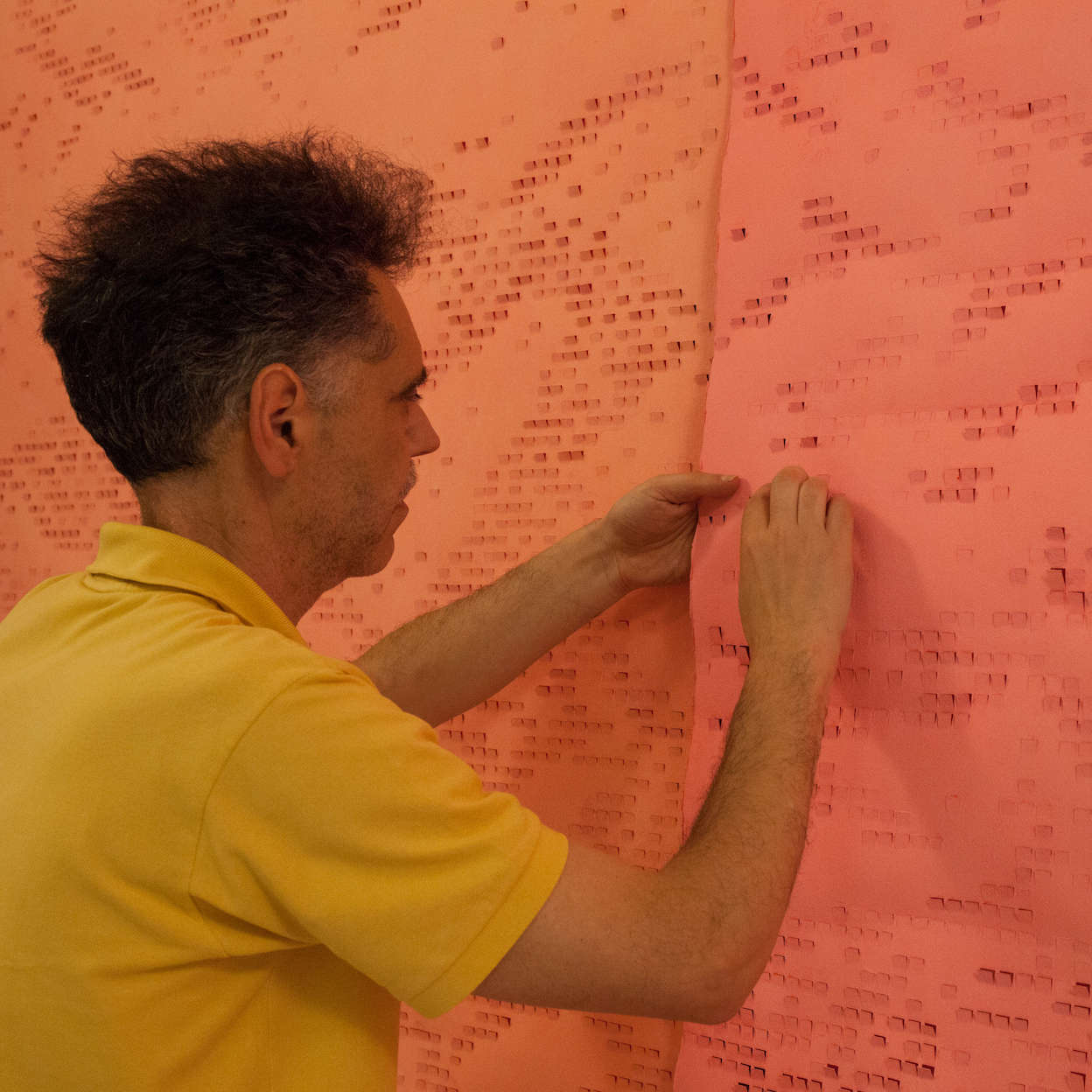

It’s about creating an approach that takes into account the time we are in and the time of fruition and not just how the works fit into the physical space. This is what I tried to accomplish in 2018 at the Gemellaro Museum in Palermo for the Manifesta collateral event in which I made exhibits belonging to different geological times dialogue with works by Marinus Boezem, Maurizio Nannucci, Antonio Muntadas, Paolo Parisi, Domenico Mangano, Salvatore Arancio, and Gianni Melotti. Works/interventions-from techniques as disparate as neon, drawings, ceramics, paintings, videos, sculptures-that made us reflect on the parameters by which we reflect on the passage of time, its perception, but also on the time of the process of the work to exist in dialogue with that employed by the viewer to relate to it. An aspect that led me to explore, for an exhibition also in 2018 at Galleria Poggiali in Florence, how artists famous for their work on video such as Grazia Toderi, Park Chang-Kyong and Slater Bradley understood the perception of time when they use other mediums than video: a medium that by its very nature develops over time and is made of time. It is an attitude of course that has to take into account the new social changes and the various debates on the subject that have since become more and more numerous. Thus, since 2020, I have found myself questioning time specificity by means of conversations with various curators such as Giacinto di Pietrantonio, Angela Vettese, Stefano Chiodi, Giorgio Verzotti, Andrea Cortellessa, Adelina von Fürstenberg, Jens Hoffmann and Charles Esche. Conversations published in catalogs produced by Frediano Farsetti Gallery on the occasion of a cycle of three exhibitions that investigated different themes. The last exhibition, the one with Gerwald Rochenshaub, Riccardo Guarneri, and Jose Guerrero, for example, by putting into dialogue three different generations, but also three different modes of work-such as abstract/analytic painting, the modernist object, and photography-we investigated the use of abstract codes as a way of reacting to the flow of digital images that we ourselves help to produce. This theme was actually also central to Paolo Parisi’s solo exhibition that I curated at Building in Milan in 2021, which allowed us to reread his works from different years such as pixelated abstract paintings from 2015 with works from the 1990s, but also with works designed for the occasion.

To your activities as a fair director and curator of exhibitions in alternative spaces, but also in institutional museums however we must also add your role as a professor.

Yes, we do. In recent years I have extended my practice of trying to combine field investigation with a theoretician’s vision also to my practice of teaching digital cultures within various Italian academies and polytechnics. The choice was easy given that precisely in the field of digital cultures, graphic design in the time of digital, the aesthetics of “gaming,” and video in the time of the algorithm, there are no reference manuals being stories that we are still writing. For this reason, all my courses are not traversed by an aprioristic reading of the phenomena of the present with which to reread the past but rather by a question with which to open a debate: what is today, and what will be, the role of imagination and creativity in the age of ChatGPT, of digital archives and censorship obtained not through the removal of information but by their excess? This is a question we must find the answer to together with the new generations precisely to avoid teaching to use theoretical tools that are now obsolete.

In the current artistic “landscape” in 2025/2026, what attracts you most?

At this moment in history, I am interested in a new generation of artists who will and are working on empathy, but not in a sentimental sense, but rather as the ability to make us “step into each other’s shoes.” An art capable of unhinging the current contemporary solipsism, developed perhaps also as a reaction to the widespread hyper-connectedness and apparent total accessibility guaranteed by social. I am referring to practices that address the cognitive shift introduced by immersive technologies, which rather than fostering connection, often simulate involvement, leaving us passive spectators. Today, all we do is fill our mouths that we are in the age of the interactive subject, but this is not the case, or at least it is only for commercial purposes. In recent years we have seen glimpses of this being criticized, and I am thinking of Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence, presented at the 2017 Whitney Biennial: an experience usable from a VR viewer in which the viewer helplessly witnesses-as when he or she enjoys other images online on his or her electronic devices-a brutal street assault carried out by the artist himself, transformed into an animatronic doll, with the mumbling of a Jewish prayer in the background amplifying the estrangement. Or I’m also thinking of Jon Rafman’s In View of Pariser Platz, in which the visitor to the 2016 Berlin Biennale (again through a VR visor) went from being immersed in an enhanced, glittering version of the panorama seen from the terrace overlooking the Brandenburg Gate only to see himself or herself fall because the pavement, in the images gave way, as the sculptures came alive: a dog swallowing a lion; an iguana devouring a sloth. In both cases, the goal of these artists is not simply to experiment with a new technology, but to induce the viewer to reflect on his or her own relationship with immersive devices, which generate an illusion of participation but, in reality, reset all forms of critical control over the real. The resulting experience is a psychophysical vertigo, a perceptual excitement that proves deeply disturbing. Here empathy is not reassuring, but a critical tool that lays bare our inadequacy to act. At a time when the language of gaming was being increasingly normalized and adopted in visual culture, these works denounce the loss of historical perspective: they show us a reality devoid of temporal depth, where it is no longer possible to imagine the collective consequences of our actions. That is why I am attracted to the new generations that are taking up this challenge and entering this kind of research.

The artists you talk about that you might be interested in in the coming years is because ...

... because they could help us re-learn how to look in an involved way at a world saturated with images. Today we are immersed in an excess of self-representation -- selfies, stories, Zoom fatigue -- that fuels an illusory sense of presence, but in reality generates an exposure to emptiness. This visual vertigo is an increasingly urgent issue, especially with the normalization of digital archives to which we entrust any kind of our memory, but also with the arrival of new computational systems capable of processing such massive masses of data in real time. This is the reason for the spread in such a short time of ChatGPT that we are using it as a more creative and intuitive search engine. Here again we are helped by works from the recent past such as the two videos that took on and critiqued the tutorial aesthetic and that were Grosse Fatigue from 2013 by Camille Henrot - with which she won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale that year - and Being Invisible Can Be Deadly (also from 2013) by Hito Steyerl. In the first case we were faced with the history of mankind told in 13 minutes through a frenetic montage of images moving across a desktop full of overlapping windows from various digital archives including that of the Smithsonian Museum. While in the second, the artist constructs a layered and disturbing montage, mixing archival video, simulated reconstructions and voice-overs to reflect on the relationship between being visible and being watched. Art, in these cases, no longer seeks to make the invisible visible, but to dismantle the very logic of the visible. The empathy that emerges is neither linear nor reassuring, but perturbing. These are the challenges I am interested in observing in new generations of artists. It is the same challenge that led Rebecca Moccia in 2024 to represent Italy with the project Ministries of Loneliness - the multichannel installation and tactile thermographs of Cold as You Are - at the 15th Gwangju Biennale. Or Elena Mazzi, who back in 2015 at the 14th Istanbul Biennial created a site-specific project with which she anticipated many of the contemporary urgencies related to ecological memory and the mobility of knowledge. As well as Kamilia Kard and Caterina Biocca, although in different ways, investigate the implications of an emotional interaction between human and digital. So do Irene Fenara or Ambra Castagnetti make us reflect on the impact of new technologies has changed the way we feel looked at. All these artists just mentioned do not simply use new media, but question the capacity of art, culture, and creativity to transform the way we inhabit time, memory, and collective space.

So your interest is not related to their use of new technologies?

No, it is not the use of technologies per se that attracts me. That was a typical key to the transition between the 1990s and 2000s, inherited from the early video experiments of the 1960s, from Nam June Paik onward, and related to the tension that emerged in the transition between analog and digital. Today, however, what should interest us is “how” some artists-even of the new generation-critically reflect on the cognitive and cultural impact of technologies in everyday life. Their works do not represent the digital, just as they do not merely present it, but immerse us in it as in a new existential condition. That is, they go beyond simply giving body and substance to what Luciano Floridi referred to in 2016 as the "infosphere": an environment in which facts coexist with traces of them on the web, kneading the present with the past into a single condition and making the concept of truth replace that of plausibility. It is this new reading of reality that should help us realize that paradigms of judgment about the world and art have changed. For example, we all fell into the same hasty judgment when, after the pandemic, there was an international preponderant return of figurative painting attributing it only to market needs to create a swing in demand. Instead, taking a closer look at the paintings of Sasha Gordon, Wang Yuyang, Kerstin Brätsch, Jadé Fadojutimi, Moka Lee, Flora Yukhnovich, Remus Grecu, Dhewadi Hadjab, Alioune Diagne, and even Farah Atassi, Anna Weyant, Richard Colman, Burna Boy, and Louis Fratino are all united- even in their aesthetic, technical, and activist statement differences - by an analytical veiling, hospital and cold approach produced by the influence of digital images in general in which these artists were born. In particular they were influenced by a new and widespread gaming aesthetic in the perception of time and the duration of images in general. The only one who talked about this new paradigm, without fear of being misunderstood, was Hans Ulrich Obrist who has discussed, since 2021, extensively the influence of video games on contemporary art in various contexts as well as leading him to curate the exhibition Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age (2022-2023), ala Julia Stoschek Collection in Berlin. Having said that, I am more interested in those artists who seek and will seek to work on an eliminating the distance between art and life (in the time of the infosphere) in order to make us reflect not on how we represent but rather practice our digital everyday. In this sense, I see a profound continuity with the relational and post-production practices of the 1990s, but which must necessarily be reread today in light of the immersive, fragmentary and hypermedia logics of the present.

Can you explain more about this reference to the past and the relational art of the 1990s that you call into question in order to better understand the current artistic landscape?

This is where the role of the critic, which is different from that of the curator, comes into play in reading the present. The relational aesthetics of the 1990s and 2000s (with artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Thomas Hirschhorn, Mario Airò, Maurizio Cattelan, Cai Guo-Qiang, Surasi Kusolwong, and later Wolfgang Tillmans, Pawel Althamer, Elisabetta Benassi, Koo Jeong A, Tino Sehgal, and others) anticipated society’s need to become active and engaged protagonists. But from 2012 onward, with the spread of the sharing economy and social media, this participation took on new coordinates. These digital tools seemed to democratize interaction, but in reality they fueled a new phase of capitalism based on the dematerialization of products by turning them into services and bringing us to the threshold of a new attention economy. Artists active in this period show us that mere participation is no longer enough: responsibility is needed. Their work lays bare the ambiguities of continuous immersion in data flows, many of which we produce ourselves. It is these practices that make us reread with new eyes even the works of thirty years ago, and the broader meaning of artistic engagement. Today art can no longer be just a critical mirror, but an experiential device capable of generating awareness, crossings and alliances. This is where the real space of empathy is played out and will be the terrain on which the next artistic generation will be measured.

The 1990s are the years in which you started to deal with contemporary art: can you tell how it happened?

Yes, I started dealing with art in the first person very early, perhaps too early because I was a senior in high school when in 1996 I participated in the organization of the first edition of Tuscia Electa, curated by Fabio Cavallucci. It was a very ambitious project since it consisted in inviting international artists residing in Tuscany, from Jannis Kounellis to Joseph Kosuth, from Jim Dine to Betty Woodman, from Luigi Mainolfi to Gio Pomodoro, to make site-specific interventions in public places in Chianti, such as Romanesque parish churches, villages, squares or Renaissance villas. It was the same year that he debuted, with the same strategy, in the Chianti area of Siena Arte all’Arte promoted by Galleria Continua. It was the time when we were leaving the deputed places of art to dialogue with everyday life and broaden the public debate. It was my job to follow the artists in the design and installation phase, and to make the works accessible to a non-specialist audience, I also invented a system of self-taught guides. It was there that I realized how art could be a tool to activate a real dialogue with people and places, without barriers or filters. In the following years I continued to collaborate with Tuscia Electa, which expanded to other municipalities besides Greve in Chianti, and in 2000 my collaboration with Pier Luigi Tazzi began. In parallel, I was studying at the University of Siena with Enrico Crispolti and began working with the Base / Progetti per l’arte collective in Florence, which opened in 1998 in front of the City Lights bookstore. Base’s activities, even today, are not signed by a single author but, by agreement, by the whole collective, which is made up - this is its peculiarity compared to other spaces of this kind - of artists of different generations and who use different expressive languages, but who find a point of contact in the practical action of inviting other artists to exhibit in the city and broaden the themes of the debate on the role of art. What I learned from Base-and what I gave back to the project by trying to coordinate it as best I could over these twenty years-is the idea of “collective curating.” I was able to develop such reflections at a time when curating, at the turn of the 2000s, was changing roles fast. In fact, the idea of the thematic exhibition had become established as a means of overcoming the limitations associated with traditional artistic languages and techniques, offering art the possibility of confronting the new liquid modernity and a global and interconnected reality, now made concrete by the spread of the Internet. The artist at that time increasingly seeks - in response to the spread of self-produced images by everyone - to produce minimal and anti-photogenic events that manage to raise the public’s level of attention in its practice of its everyday life. This is the mode adopted by these artists to create a new kind of political, or rather engaged, art committed to changing the Western-centric, colonialist and patriarchal parameters of the previous century. The 2001 Venice Biennale, curated by Harald Szeemann and titled open, and the 2002 Documenta 11, directed by Okwui Enwezor, witnessed and legitimized at the institutional level this new post-colonialist and inclusive trajectory.

What has been your reaction to this?

Trying to initiate projects that would help highlight this change. In the following years, new generations, rethought this kind of activism by not just wanting to improve the world, but by focusing on rethinking how to build a new sense of belonging and collective identity. It was during this period that a strong reflection on the reactivation of collective memory developed. It was a way of working on traditional monuments-those that were on pedestals-but intangible and not impositional. Artists I worked with in those years such as Anri Sala, Stefania Galegati, Jonathan Monk, Rossella Biscotti, Diego Perrone, Marinella Senatore, Joanna Billing, Elisabetta Benassi, Roman Ondák, Matteo Rubbi were acting on this from the point of view of content. From the formal point of view, all these artists had in common that they used any material and technique because they chose it according to the site-specific project they had to realize. Taking into account, on their part, the context in which the work was born and which it was going to inhabit was a way of reacting to globalization and the loss of physical references. The world at the time of Google Maps was starting to become extremely large, but also extremely small. Toward the end of the 1910s we then saw another change on the part of these artists or rather a bringing out more clearly what they were interested in. That is, work on the perception of time. It was not just site specific, but increasingly a time specific approach, linked to time and the cultural and political condition of the moment. Today that dimension has transformed again. We find ourselves, as I mentioned in previous answers, in a digital ecosystem that shapes our perception of the present. I believe that precisely this attention to the here and now, to the everyday experience and responsibility of the viewer and the acter, is the thread that connects all the artistic practices that have always interested me, from those of the 1990s to those of the current generation, which is confronted with the fragmentary, relational and hypermedia logics of the contemporary infosphere.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.