In a long interview in 1996, Federico Zeri carefully analyzed, one by one, the problems, related to the study (and partly to the profession) of art history in Italy. Despite its extraordinary cultural heritage, in Zeri’s eyes, in those years the Italian peninsula still continued to show significant limitations and obstacles. The picture taken by Zeri, in his interview with Bruno Zanardi in the beautiful house in Mentana, brought out an aspect that conditioned and still conditions the possibility of heterogeneous development of studies and art itself throughout Italy: many expressions, occurrences, styles and languages of art corresponding to areas of the Peninsula considered marginal, appeared completely excluded from interest, and therefore, from art historiography and criticism. This phenomenon, in Zeri’s opinion, happened not only and not so much in deference to a proven tradition of studies that saw, exclusively in central and northern Italy, the major artistic centers, but was connected above all to an attitude, in this area, that was purely and historically “mercantile,” “commercial.”

As we know, this is not how it should have been, at least, not so much that it still affects things. Historical as well as artistic analysis shows how the cultural production of the elites of the courts of Rome and Florence represented, yes, the main node of attraction and enhancement of the artistic heritage, since there the creative activities were concentrated and there was, early on, the establishment of a vigorous patronage and a highlyhighly dynamic art; on the contrary, in the southern regions, below Campania and particularly in the extreme tip of southern Italy, Zeri himself noted a dearth of interest and systematic studies, suggesting that these territories appeared to be scarcely significant in terms of artistic production, collecting and cultural appreciation. It is as if to say that there was little or nothing really relevant in those lands to know, to acquire, to appreciate. However, historical and archaeological evidence shows that this limiting tendency has partly been overcome. It has long been recognized that the territorial diversity and variety of artistic expressions peculiar to each Italian region constitute fundamental elements for understanding the historical and cultural richness of the entire country. Therefore, even the most peripheral areas have played a crucial role in defining its identity and landscape variety. Indeed, it is precisely such territorial fragmentation that has been fundamental in composing the very identity and extraordinary uniqueness of our country.

A second element that enriches our reflection, is that of another scholar, Luca Nannipieri and his essay, A cosa serve la storia dell’arte, published by Skira in 2020. Art history-as it is made clear in the book-does not “serve” only to keep museums and galleries alive, to produce exhibitions and displays, but if anything, and it is important to emphasize this, it is a means of opening up new “spaces” more or less visible, real or even imaginary where pictorial works, archaeological finds, or sculptures but also the multiple expressions of contemporary art and local craftsmanship find their place: all “objects” these that represent the different manifestations of a complex artistic reality. And it is precisely to make it more comprehensible, it is to transcend from a simple visual observation that the interaction between the human element and the artistic object is needed. There is a need for those who can give voice to it, that is what the role of the scholar is, to illuminate works and places with his “word,” with his experience, his expertise, his passion. We must also remember that art history is a discipline that is configured as dynamic and subjective; it relates to each individual differently. Art “serves” everyone: the patron, as an instrument of exchange and investment; scholars, as a means of analyzing the events that led to the creation of the works; the artists themselves, as a process of expression and innovation; and finally, the viewers, who through the aesthetic and cultural experience, experience often unrepeatable moments. In a word, in short, art activates social dynamics, involves communities and territories, and promotes a sense of belonging and collective identity. Recent studies have also shown how art can contribute to mental and physical well-being, promoting the reduction of stress and anxiety and keeping certain diseases at bay. In short, dealing with art saves us, and keeps us away from experiencing the sense of loss that is inherent in every human being. For this reason we should support anyone who deals with it, because it possesses a great power: it becomes a messenger of beauty.

Instead, what emerges is a rather dramatic fact because this “role” of art and those who work in it, has not, voluntarily or not, been fully understood yet, when not discredited and underpaid. Factors such as these further complicate matters, because in the eyes of many, those involved in the fine arts continue to have no significant impact on society, reality, territories, and the existing. The scant consideration given to it-particularly in certain parts of Italy where a market that would allow the development of these territories has never flourished-has also affected at times the inability to care for and protect much of a heritage that at this geographic height has always been very rich and was already present from ancient times. But why did we make these premises, even recalling the reflections of two well-known scholars, in order to talk about the Giuseppe Maria Pisani Gipsoteca of Serra San Bruno in Calabria?

On the one hand, to delimit the conditions that make it difficult to develop studies and the “explosion” of cultural ferment in some areas of Italy, as has often happened in Calabria as well. On the other hand, this premise is also intended to promote the actions of those dedicated to these activities and to highlight the gestures of beauty that, for example, a place like the precious Pisani Gypsoteca is trying to express, despite obstacles, ostracism and indifference. Just persevere: every “seed” planted with care will bear fruit sooner or later. It is essential to continue to cultivate patience, trust and courage, not only for the time of our lives, but also for the time of future generations. Not only for ourselves, for the spaces of beauty we have created, but also for those who will come after us. Art historian Domenico Pisani, a scholar known especially in the area, tells us about the adventure that led him to inaugurate, just over a year ago, the Gipsoteca dedicated to Father Giuseppe Maria Pisani in Serra San Bruno.

ADFS. How did you manage to open this space?

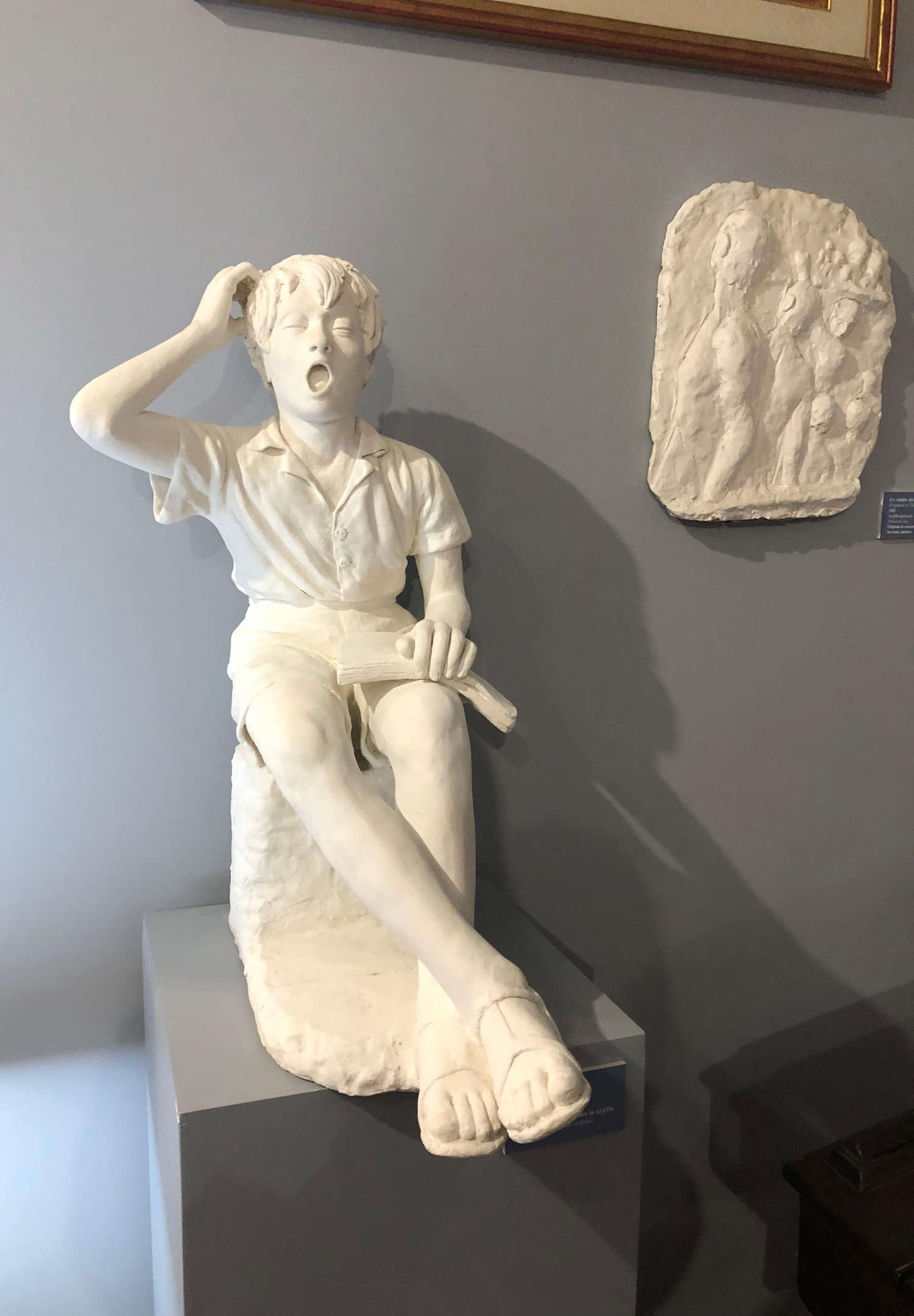

DP. A few years after my father’s death in 2016, his sculpture studio-workshop, overlooking the Ionian Sea (in Soverato to be precise) began to show signs of decay as it was no longer used. Materially, dust was beginning to cover the plaster casts of his works but, ideally, the blanket of oblivion was beginning to be seen on the artistic production of a lifetime, made since the 1940s, Overcoming an initial moment of sadness, worried by the thought of a future dispersion of all that that had been patiently preserved and collected, I cherished the idea, supported by my family, of opening a gipsoteca in Serra San Bruno, the town where my father was born and had lived until 1970. Thus more than 100 plaster casts were packed and transported, some of them large, and found space in a building that had recently been renovated and adapted as a museum space, taking into account the needs of the disabled and safety regulations. With my brother John, an architect, we devised the layout, the visitor routes and the placement of the works in the exhibition spaces. Once the bureaucratic problems were overcome, we opened the facility on September 15, 2024.

What does it collect and what is its mission?

The gipsoteca mainly collects the plaster casts of Giuseppe Maria Pisani’s sculptures, translated into marble or bronze during the second half of the twentieth century, but his pastels also find a place in the visiting paths, especially those that have as their theme the life of the Carthusian monks, who have been present in Serra San Bruno, with alternating events, since 1091. In addition, in order for those wishing to enjoy the museum spaces to understand the sculptor’s training, anatomical plaster casts, casts from life and especially reproductions of classical statues donated to him in the 1950s by his teacher Gaetano Barillari, a Divisionist painter who had studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples in the early twentieth century, were displayed. Also found a place in the reconstructed workshop in one of the rooms were sculptor’s easels made for him by Serbian carpenters, as well as pigments and artistic tools that had belonged to his grandfather, who had been a good painter of the Neapolitan school, a student of Domenico Morelli. In addition, in a large display case at the beginning of the itinerary, various accounts of the activity of the artist-craftsmen of Serra San Bruno, who had distinguished themselves mainly as cabinetmakers and stonemasons, but also as brass workers, marble workers, gunsmiths, and goldsmiths.

What kind of activities are planned?

Every museum space runs the risk, if it does not program cultural activities, of becoming a container of objects that, although aesthetically pleasing, remain far from the understanding of those who are not versed in the specific subject. To contribute to the knowledge of the area, in little more than a year of its existence, the gipsoteca produced a temporary exhibition centered on the figure of Sharo Gambino, a journalist, meridionalist but also a painter who, in the 1950s, had achieved a fair amount of success with his paintings exhibited in various Calabrian festivals. The catalog was published by the publishing house we founded for the occasion: Gipsoteca Pisani Edizioni. Another anthological exhibition dedicated to Giuseppe Calabretta, the last epigone of a long line of artists who had combined painting, photography and anthropological interests, is being prepared for next summer. There has also been no shortage of book presentations and small concerts over the past year that have attracted audiences of a diverse nature.

What are the obstacles for a museum in Calabria to have a real impact on everyone’s lives?

One must avoid self-referentiality and operate respectfully and serenely in the social fabric. The risk is “the ivory tower” or “the cathedral in the desert.” Fundamental is the contribution of the schools in the area to make young people understand how much the history of the twentieth century is still alive in everyday life and how much the artists, specifically from Serra San Bruno, have affected (not only aesthetically) many towns in Calabria, with their architectural and decorative language, in the formation of a taste that for centuries has been the heritage of the Calabrian Serre.

What are the forms of resistance to difficulties that the gypsum museum activates?

Let’s take an example: resistance to the mistaken idea of a museum not open to the outside world can be overcome by promoting the study and historical and archival research on the art and craft of Serra San Bruno, the city’s identity heritage. My father had collected a number of documents and specific publications on the subject and thus helped many university students compile their dissertations. By making this material available to the public, the Gipsoteca has activated a mechanism that can be of real help to those who intend to study or even simply inform themselves. In addition, the bookshop and museum gadgets can be considered an extension of the visit itinerary that enriches the offerings of the gipsoteca and allows one to pleasantly materialize the memory of the experience lived in its spaces.

What can we do so that in Calabria we can overcome those historical and cultural conditioning that Federico Zeri noted?

The only thing that can be done is to contribute to studies with systematicity and rigor. Calabria preserves a misunderstood artistic heritage. Remembered by most only as the homeland of Mattia Preti or as the custodian of the Riace bronzes and little else, it bears a burden of prejudice that makes it appear to be at the tail end of the list of southern regions. Yet thanks to a century of studies inaugurated by Alfonso Frangipane, the pioneer of Calabrian art history, it has been possible to learn how much in its past this region has been rich in ferments that, through important monasteries, noble families and high prelates, have contributed to an extraordinary interweaving of microhistory and macrohistory that today can be understood only by recomposing (at least ideally) the fragmentation caused by notable natural disasters, principally the 1783 earthquake. After such studies, many of them of genuine scientific value, it is reductive to speak only of picturesque aspects or phenomena of anthropological significance relating to this land. It is true that a Calabrian scholar must travel miles of often impassable roads to appropriate the land or wander among libraries and archives considerably distant from each other to complete his or her research, whereas in Naples, Rome or Florence there is ease in moving among cultural institutions. However, the charm of Calabria is just that, it activates mechanisms of serendipity.

And how to do so that this territory, where a new “space” has been bravely opened, is artistically alive and speaking as Luca Nannipieri hopes?

In addition to the promotion of exhibitions, set up not for commercial purposes but to tell the story of the territory, it is necessary to describe the artistic phenomena of Calabria with the experience of those who live it every day to make them understood by a wider audience. This is precisely one of the most interesting aspects of this “craft.” Going beyond the purely aesthetic interest of an art object to bring out its historical and artistic value fosters its interaction with human beings. In the present case, it is very important to make it clear, through the establishment of a gypsoteca in our case, that those who visit them are not just going to see a dumb aggregation of calcium sulfate in more or less dynamic forms, but are approaching a matter that pulsates, speaks, tells, lives. Highlighting then the relationships among the sculptors of the twentieth century in this region is not an easy thing to do, but it allows one to understand -- to those who want to listen -- the dynamics that led to the creation of bronze or marble monuments scattered in the squares, schools or collections of our cities in order to overcome that indifference to which they are subjected by those who do not yet have the tools to understand them.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.