The monumental Selva-Lazzari salons of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, dedicated to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting, were inaugurated today in the presence of Minister of Culture Dario Franceschini, President of the Veneto Region Luca Zaia, Venice City Councilor for Tourism Simone Venturini, Museums General Director Mic Massimo Osanna, and Galleries Director Giulio Manieri Elia.

The unprecedented itinerary on the first floor presents a selection of sixty-three works, some of which have never been exhibited or admired after restoration work carried out for the occasion. Among the restored masterpieces are Tiepolo’s The Chastisement of the Serpents, a canvas more than 13 meters long from the Venetian Church of Saints Cosmas and Damian; the Deposition of Christ from the Cross by the Neapolitan artist Luca Giordano, exhibited for the first time within the permanent collection; the scene of Erminia and Vafrino discovering the wounded Tancredi by Gianantonio Guardi, the only canvas in a cycle inspired by Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, returned to Italy after a complex collecting process; Padovanino’s Parable of the Wise Virgins and the Foolish Virgins, presented for the first time ever to the public and remounted on the ceiling as it was originally; and the Venetian painter Giulia Lama’s Judith and Holofernes. The new itinerary presents particularly significant themes and protagonists of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting production, completing the first floor museum display, which spans a time span from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century.

“With this initiative,” declares director Giulio Manieri Elia, who curated the project together with deputy director Roberta Battaglia and with the collaboration of Michele Nicolaci, “the Galleries become the privileged place, on the world stage, to learn about an important and still little-known piece of art history, in particular painting in Venice and the Veneto region in the seventeenth century, which for the first time is represented in the museum with a space entirely dedicated to it. Also an absolute novelty is the layout of the 18th-century hall, which, next to previously unseen masterpieces, will present a sort of ’museum within a museum,’ reserved for one of the art geniuses of all time, Giambattista Tiepolo.”

Room 5 houses large-scale works from 17th-century Venice mostly from churches and religious buildings in the city, including monumental altarpieces by Luca Giordano, such as the Deposition of Christ from the Cross, and Pietro da Cortona’s restored Daniel in the Lion’s Den. Alongside these masterpieces, there are also important examples by Bernardo Strozzi, Nicolas Régnier, and Sebastiano Mazzoni, whose unpublished Strage degli Innocenti, just purchased by the state, is on display.

A number of thematic focuses have been conceived within the room, such as the one dedicated to the decoration of the Venetian church of the Ospedale degli Incurabili, which was destroyed in 1831, of which Padovanino’s Parable of the Wise Virgins and the Foolish Virgins is now presented for the first time ever. Also visible in the same room is the large fragment of Bernardo Strozzi’s Parable of the Wedding Banquet, also part of the Incurabili’s decoration, acquired by the state in 2016.

Room 6, on the other hand, offers an overview of the varied Venetian pictorial production of the 18th century, with some thematic subsections. Opening the room is Gianantonio Guardi’s Erminia and Vafrino scene, which is now presented to the public after restoration. The long south wall of the hall is dedicated to Tiepolo, whose monumental Chastisement of the Serpents is on display, while two other sections are edicated to landscape and interior painting with Pietro Longhi’s famous scenes. Among the various protagonists is the Venetian painter Giulia Lama with Judith and Holofernes.

In both halls, great attention is proposed to the recovery of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century decoration of the School of Charity, now incorporated into the museum itinerary on the second floor. In particular, from the Sala del Capitolo, now Room I of the museum, come Gregorio Lazzarini’s Circumcision and Gianantonio Fumiani’s Dispute of Christ with the Doctors, while from the Sala della Nuova Cancelleria comes the cycle of canvases inspired by stories from the Old Testament, in which several personalities from the Venetian Academy of Fine Arts took part, including Giandomenico Tiepolo, son of Giambattista.

The inauguration of the new salons was supported by Venetian Heritage, with funding of 584,764.34 euros for the entire set-up and restorations. Other restorations were funded by the Ministry of Culture (Padovanino, Parable of the Wise Virgins and the Foolish Virgins), Intesa Sanpaolo as part of the Restitutions project (Pietro da Cortona, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, Nicolas Régnier, Annunciation) and by private companies as part of the Italian Stock Exchange’s Rivelazioni project (Giulia Lama, Judith and Holofernes and Francesco Ruschi, Saint Ursula).

The completely renovated LED technology lighting system of the new rooms is due to iGuzzini illuminazione, which has always specialized in museum and cultural heritage lighting.

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari rooms. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari rooms. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari rooms. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari halls. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari halls. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

|

| The new layout of the Selva-Lazzari halls. Photo by Matteo De Fina |

“The works of the seventeenth century exhibited in Hall 5,” explains Roberta Battaglia, deputy director of the Gallerie dell’Accademia, “stand in close continuity with the seventeenth-century paintings of small and medium format, destined for private collecting, presented in Room 3, while those of the eighteenth century exhibited in Hall 6 find completion in those of Room 8 of the Palladian wing, exemplifying the international success enjoyed by many artists working in Venice in the eighteenth century (Sebastiano Ricci, Jacopo Amigoni, Canaletto, Bellotto). Thus comes to a conclusion, some years after the challenging restoration of the monumental complex directed by Tobia Scarpa and Renata Codello, the arrangement of the permanent collection, with regard to the sections of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in the rooms around the Palladian courtyard. Hall 5 is dedicated to large-format seventeenth-century paintings, mostly of ecclesiastical destination, which came to the museum following nineteenth-century demanializations. Venice, a city that has always been open to the presence of ’foreign’ artists, was marked during that century by fundamental grafts of foreign painters, the only ones able to bring a breath of fresh air within a local artistic tradition that tended to be conservative and little inclined to change, dominated in the first two decades by the heirs of the great workshops of the second half of the sixteenth century.”

The itinerary opens with two paintings from the ceiling decoration of the Church of the Incurabili: the large oval with the Parable of the Wise Virgins and the Foolish Virgins by Padovanino, restored for the occasion and on public display for the first time, anchored five meters high thanks to a complex mechanical system, and the fragment with the Parable of the Wedding Banquet by Bernardo Strozzi, which entered the museum following a recent purchase by the state. Of the portraiture conducted by Strozzi in Venice for important state and church offices, the Portrait of Giovanni Grimani offers a testimony, recalling the great full-length portraits by Pieter Paul Rubens and Antoon van Dyck, admired by the artist in his native Genoa. The portrait introduces Strozzi’s most important work in the Galleries, namely Supper in the House of Simon, an original recreation of the traditional suppers of Venetian painting, dating from the artist’s Genoese period.

Another painter who came to the lagoon from other parts of Italy is the Florentine Sebastiano Mazzoni, who arrived in Venice in the 1740s. His originality and unruliness are documented by three works on display in this room: the unorthodox Annunciation, the St. Catherine Refusing to Worship Idols, set with a bold foreshortening from below emphasized by the presences of painted architecture, and the Massacre of the Innocents, a masterpiece recently resurfaced on the market and purchased by the museum just two months ago. Continuing on, one encounters Nicolas Régnier and Pietro Vecchia, while among the greatest surprises that the layout of this room holds is the entry into the museum’s permanent collection of two important altarpieces, Pietro da Cortona’s Daniel in the Lion ’s Den, and Luca Giordano’s Deposition of Christ from the Cross, both dating from the 1760s: they constitute two highly advanced examples of European art of the century, destined in different ways to dialogue with developments in Venetian painting in the second half of the seventeenth century. Next to Luca Giordano’s altarpiece are two canvases with a biblical theme by Francesco Solimena, in which the lessons of Giordano and Mattia Preti are combined with the Roman classicism of Carlo Maratti: coming from an important Venetian collection, that of the Baglioni family, they bear witness to the special preference accorded to the Campanian painter by Venetian collectors in the late seventeenth century. Their placement at the close of the seventeenth-century salon is intended to create a link with the education of Piazzetta and Tiepolo, whose works are exhibited in the neighboring room, Room 6.

Hall 6 is thus entirely devoted to eighteenth-century Venetian painting. The itinerary begins with Erminia and Vafrino discover Gianantonio Guardi’s Wounded Tancredi, arranged at the opening because it is highly representative of the mildly frivolous and elegant intonation of Venetian Rococo, so as to mark a clear break from the high-drama painting of the previous century. As the tour continued, the paintings were organized into coherent groupings (by theme, genre or artist) by taking advantage of the scanning of the space into three naves, determined by the arrangement of octagonal pillars aligned longitudinally. In the right aisle, then, here is the great history painting interpreted by Giambattista Tiepolo: the Tiepolo works are preceded by a Judith and Holofernes by Giulia Lama, an expression of a singular, nonconformist personality plagued by dark anxieties that also find expression in the poetry he has long frequented. The sequence of Tiepolo’s works, arranged in chronological order, begins with the four refined youthful mythologies, executed in the early 1920s, which testify to the great curiosity, imagination and wit with which the painter approached the Ovidian text: the Rape of Europa; Diana and Actaeon; Diana and Callisto; and the Judgment of Midas. This is followed by the Chastisement of the Serpents, a canvas more than 13 meters long, dating from the first half of the 1930s whose pictorial felicity can now be fully enjoyed thanks to a restoration that eliminated the visual interference given by the many gaps that furrowed its surface. Concluding the sequence are three Tiepolesque altarpieces, not large in size, which testify to the artist’s religious production, reevaluated by critics in relatively recent times.

In the left aisle there is a long string of landscapes testifying to the commercial success of the pictorial genre in 18th-century Venice thanks to the activity of artists, mostly “outsiders,” who interpreted the theme with different sensibilities and modes. The section is opened by a large painting by the Genoese Alessandro Magnasco, made in collaboration with Lanconetan Antonio Francesco Peruzzini, who dealt with the landscape by portraying the lush forest. The series continues with a pair of landscapes by Marco Ricci from Belluno, nephew of the famous Sebastiano Ricci, who knew how to draw from the landscape tradition of sixteenth-century painting, especially Titian, of whom he was a great admirer, a marked ability to observe natural environments, captured at a particular time of day, season, as well as weather conditions. Following on the same wall are two canvases by Francesco Zuccarelli, kept in the Villa Pisani in Strà at the end of the 18th century: the Rape of Europe and the Bacchanal. Zuccarelli, who landed in Venice in 1732 after other experiences conducted in Tuscany, his homeland, and in Rome, benefited from the recent death of Marco Ricci and the close relations with English clients already maintained by his colleague, inheriting the many market demands. Completing the wall are a number of canvases by Giuseppe Zais, a native of Agordino, who pursued a more secluded career in Venice than Ricci and Zuccarelli, from whom he nonetheless drew inspiration.

The central space is devoted to genre painting and portraits, beginning with Pietro Longhi’s six sketches that depict with irony but without moralizing intent the aristocratic society of the time, carefully observed as it goes about its usual activities indoors in palaces, within rooms devoid of windows, light and air. Moving a few steps into the central space here is the Portrait of Almorò III Alvise Pisani and his family by Alessandro Longhi, son of Pietro, a committed essay of the painter’s youth marked by his father’s manners and inspired by the Anglo-Saxon scheme of conversation pieces. Completing the survey of 18th-century portraiture is the Portrait of Count Giovanni Battista Vailetti by Fra’ Galgario, an artist from Bergamo who also stayed at various times in Venice. Also in the central space, on panels arranged longitudinally face each other two genre scenes resolved in tones of rural idyll: on one side the famous Indovina by Piazzetta, to which a recent restoration has greatly benefited, and on the other the Solletico by Giuseppe Angeli, a composition of strict Piazzetta observance. Piazzetta portrays a young and sensual commoner in the act of holding under her arm a lively little dog that tries to slip away perhaps attracted by the woman’s gesture from behind, while two young men in the background confabulate with each other. Giuseppe Angeli’s descent from Piazzetta, whose pupil he was as well as the main heir at the master’s death, is also evident in the large canvas with the Madonna and Child between Saints Rocco and John the Evangelist, relating to a later period of his production. The painting, destined for the Scuola della Carità, whose coat of arms is depicted at the base of the throne, is displayed in a central position on the back wall of the room, accompanied on either side by two canvases by Giandomenico Tiepolo and Giambettino Cignaroli, also from the Scuola della Carità and belonging to the decorative cycle of the New Chancery room. The two paintings, which are almost coeval, aim to testify to the coexistence of two different eighteenth-century souls and offer two different looks at the stories of the Old Testament: in Giandomenico Tiepolo we witness the fresh observation of reality and human behavior, not without notes of playful amusement, as in the depiction of the sudden astonishment of Sarah, depicted as a simple peasant woman who has just set a rustic table under the foliage of the tree, surprised by the appearance of angels and no less; on the other hand, the scene of Rachel’s death interpreted as a solemn mourning with great emphasis placed on the rhetoric of gestures and looks. On the one hand a brisk and lively comedy, acted with the pictorial freshness and darting vitality of Tiepolo’s sign; on the other, the staging of a family drama centered on the rhetoric of affections, expressed through studied poses, in a classicist style that already heralds a sensibility of neoclassical taste.

|

| Pietro da Cortona, Daniel in the Lion’s Den (1663-1664). © G.A.VE Photographic Archives, photo by Marco Ambrosi, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Luca Giordano, Deposition of Christ from the Cross (ca. 1665) © G.A.VEPhotographic archive, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - allerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Gianantonio Guardi, Erminia and Vafrino discover wounded Tancredi (c. 1750-1755) © G.A.VE Photographic archive, photos by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Giulia Lama, Judith and Holofernes (c. 1725-1730) © G.A.VE Photographic archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Padovanino, Parable of the Wise Virgins and the Foolish Virgins (1636-1637) © G.A.VE Photographic archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Bernardo Strozzi, Parable of the Wedding Banquet, fragment (ca. 1636) © G.A.VE Photo archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Rape of Europa (ca. 1720-1721) © G.A.VE Photographic archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Chastisement of the Serpents (c. 1732-1734) © G.A.VE Photographic archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

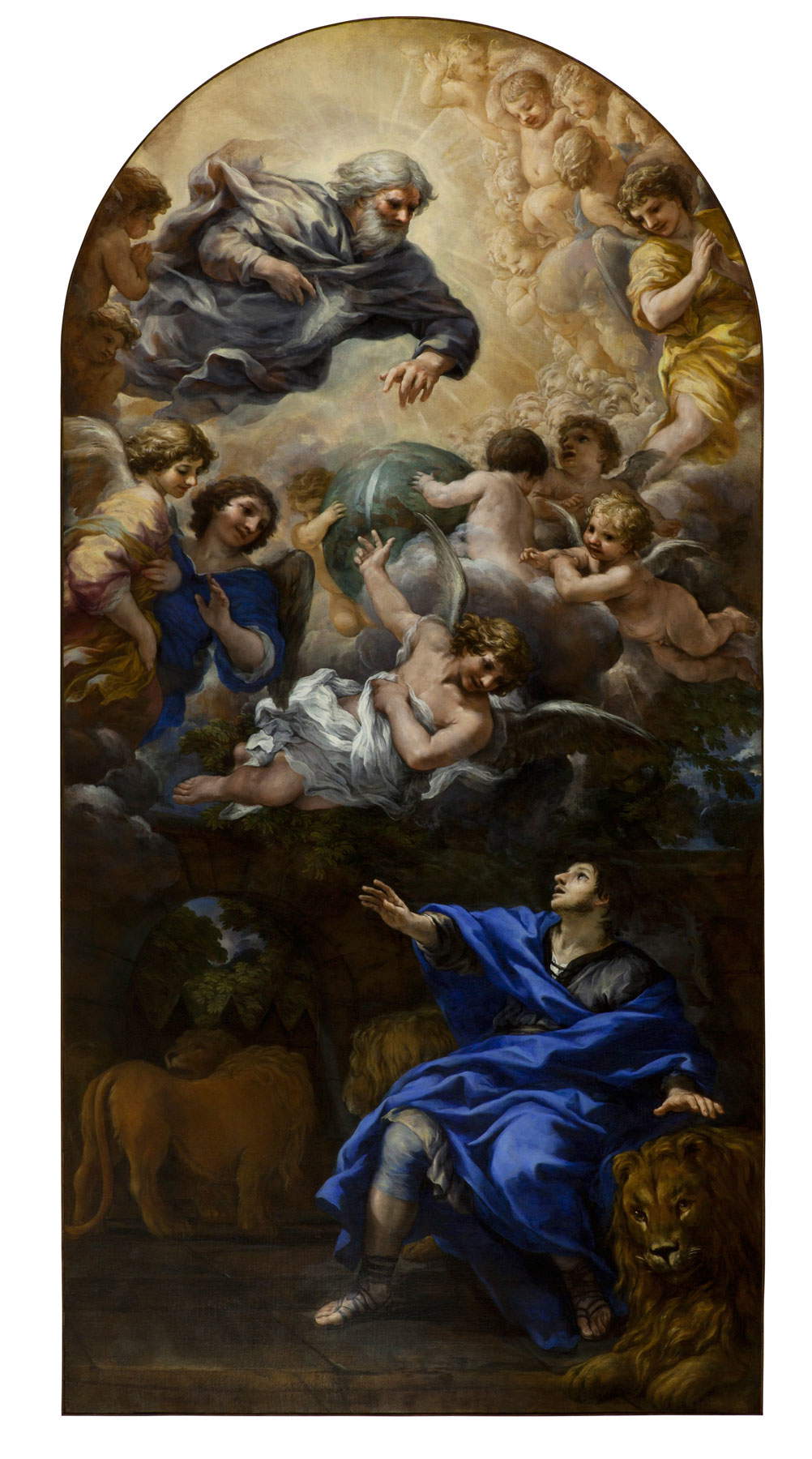

| Giandomenico Tiepolo, Apparition of the Three Angels to Abraham (1773) © G.A.VE Photographic archives, photo by Matteo De Fina, by permission of the Ministry of Culture - Gallerie dellAccademia di Venezia |

|

| New rooms of the 17th and 18th centuries opened at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.