Leonor Fini (Eleonora Elena Maria Fini in Buenos Aires; Buenos Aires, 1907 - Paris in 1996) is recognized as one of the most original and independent personalities of the 20th-century art scene and is best known for her pictorial work, but in fact she also left a graphic corpus of considerable importance, and a relevant core of this corpus is preserved at the Villa Bassi Rathgeb Museum in Abano Terme (Padua), where it entered in 2025 following the donation of Ambassador Ugo Gabriele de Mohr (Brussels, 1940), which will be discussed in more detail a little later, and which provided the occasion for the exhibition Leonor Fini and the Bassi Rathgeb Graphic Collection. Signs and Inventions from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century (Abano Terme, Museo Villa Bassi Rathgeb, November 22, 2025 to March 15, 2026, curated by Giovanni Bianchi, Raffaele Campion, Barbara Maria Savy, and Federica Stevanin).

An artist of European caliber, Leonor Fini spent her childhood and adolescence in Trieste, in a family climate that was not easy and yet was important for the development of her deep sense of independence and her capacity for transformation, elements central to her artistic production. The Central European environment in Trieste also nurtured her visual and literary culture, leading her to develop early passions for art and experimentation, although she described herself as self-taught.

After a brief period in Milan in the 1920s, where she held her first solo exhibition in 1929 and came into contact with the Novecento group, the decisive turning point came with her move to Paris in 1931. Here, although in dialogue and relationship with the main movements and protagonists of his time, including Surrealists such as André Breton, Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí, Fini always claimed his own stylistic and conceptual autonomy, refusing to formally join the group.

His painting draws inspiration from diverse and influential sources, including Italian Mannerism, Flemish masters and German Romanticism. The dreamlike and erotic vision that characterizes his works focuses on the archetype of woman understood as a powerful figure, sovereign of her own sexuality, often depicted as a sorceress, sphinx, priestess or queen, departing from the male vision prevalent in canonical Surrealism.

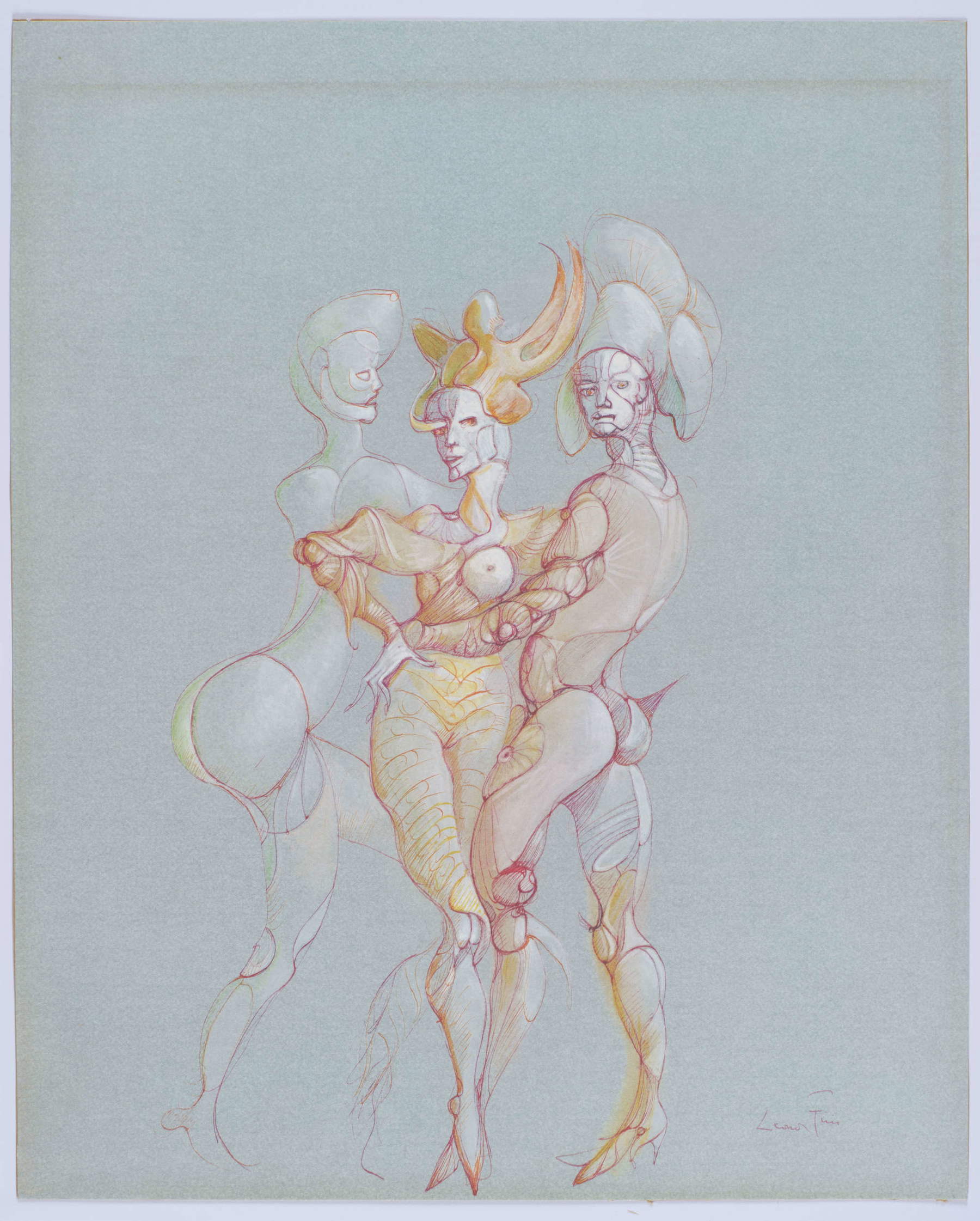

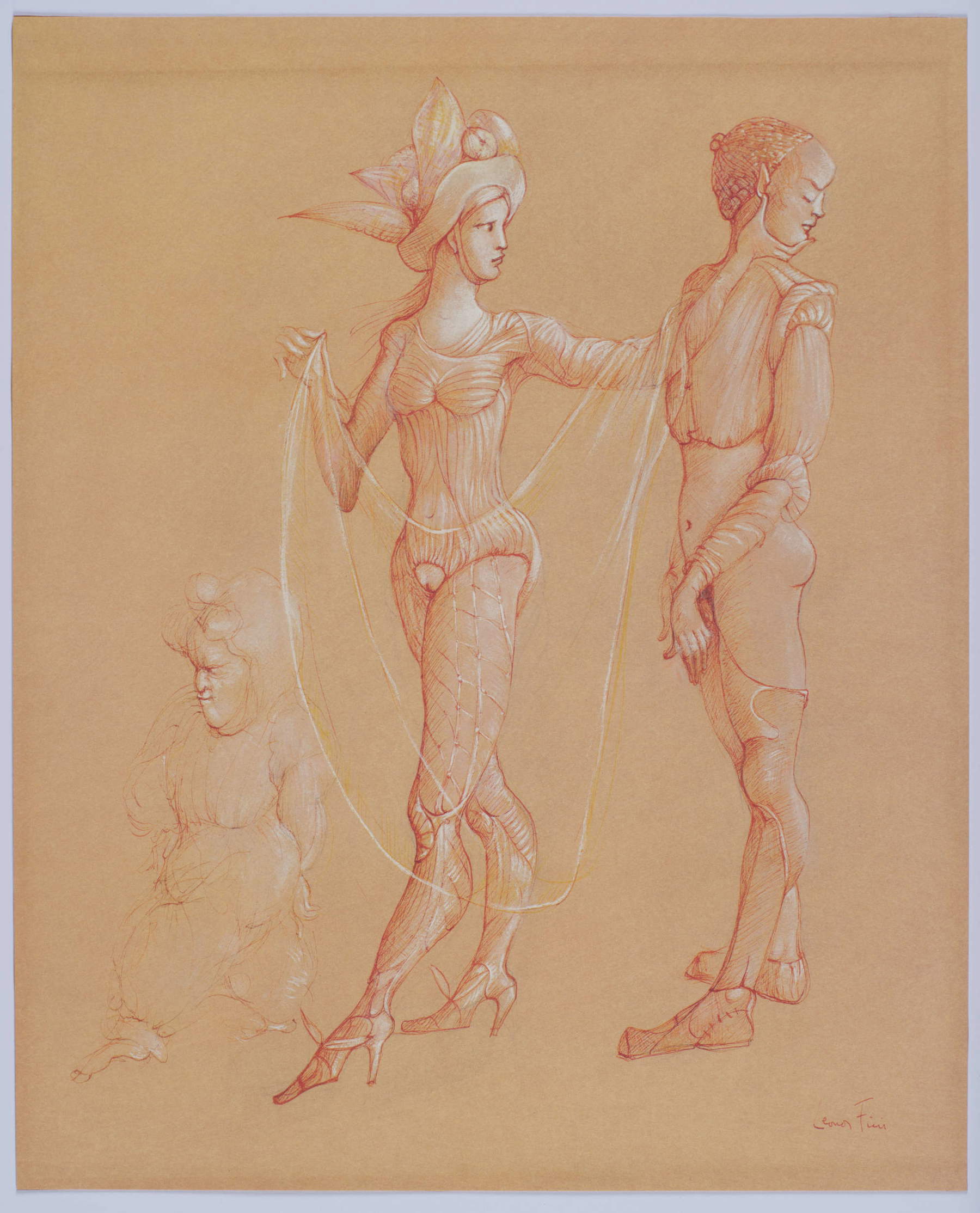

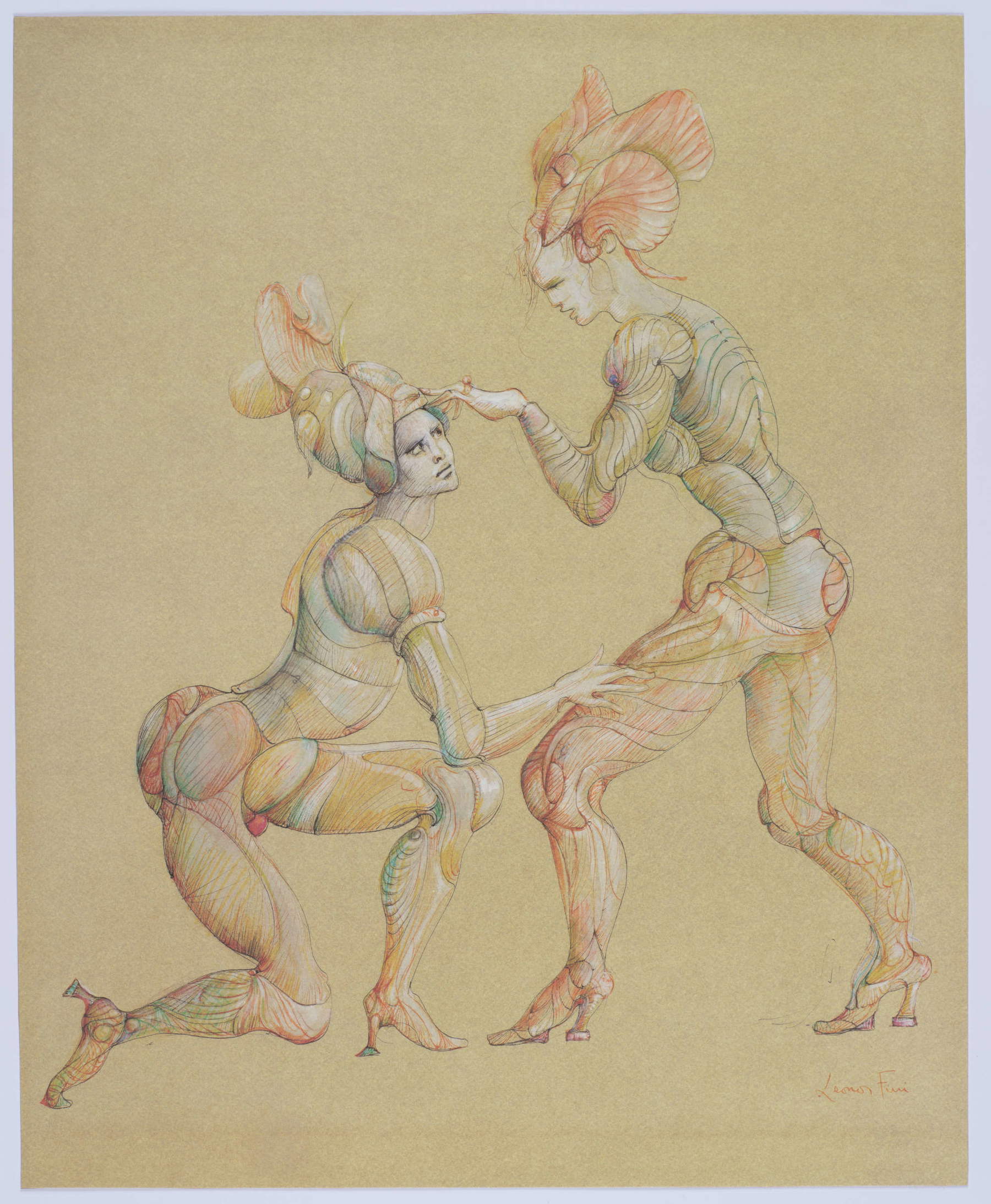

The donation of Ambassador Ugo Gabriele de Mohr (Brussels, 1940), which represents one of the most significant acquisitions ever received by the Villa Bassi Rathgeb Museum, includes a nucleus of 24 graphic works by Leonor Fini, created during the 20th century. This addition has greatly enriched the permanent collections of the Abano museum, opening the institution to artistic directions that exceed those traditionally established. Leonor Fini’s constant practice of drawing has enabled her to give rise to a considerable output of printed works, used for the illustration of poems or stories (her own or those of others) and for the creation of albums and artist portfolios. The graphic compositions in the donation, including photolithographs and etchings, outline the poetics of an international artist of the 20th century who always remained free of rigid definitions and patterns. Fini herself considered drawing, writes Federica Stevanin, as an “instrument of creative trespassing capable of absorbing and transforming suggestions from the different artistic fields she frequented such as literature, poetry, theater, as well as, of course, painting.” Her achievements on paper were described by Leonor Fini herself as a “kind of linear dream,” an “authentic fantasy” that allowed her to shape “an intimate macabre theater” in which beauty, ambiguity and cruelty coexisted. The graphic images, often enigmatic, create a mysterious and dense atmosphere, where characters seem to sleepwalk in a lucid hypnosis, performing inexplicable acts.

The graphic works included in the de Mohr donation can be traced to two main categories of Leonor Fini’s printed production: artist albums and portfolios, and books illustrated by her. A large part (thirteen works) consists of photolithographs from the limited edition volume Fruits de la passion. Trente-deux variations sur un thème de Leonor Fini, published in 1980. In this series, the artist stages, almost in a cinematic sequence, a parade of characters, mostly couples, who embody the many facets of amorous passion. Through these variations, Fini explores his favorite theme of the double, understood as otherness, instability and suffering. Tenderness, seduction, and gallant courtship are juxtaposed with violence, cruelty, and suffering in a relentless struggle between the sexes. The compositions are distinguished by the accurate and carnal depiction of the body, at times evoking figures of “skinned men,” an interest the artist had cultivated since his youth with visits to the Trieste morgue and the study of anatomy treatises. The characters, with their sophisticated accessories and clothing (masks, corsets, heeled shoes), act on a paper stage with “18th-century grace” and choreographed movements.

Other graphic works in the donation come from important collections, including Livre d’images (1971), Les Leçons (1976) and Fêtes secrètes (1978). The three present lithographs related to Livre d’images re-propose recurring subjects in Fini’s poetics, such as nude, sensual and languid female figures who exist in a liminal reality and show themselves in total self-possession. The theme of the sphinx, which Fini considered a kind of alter ego, appears combined with the theme of the double in one of these prints. For Fini, the sphinx, a half-animal, half-human hybrid being, represents the ideal condition, capable of calmly dominating humans but also being dangerous.

The silkscreen print La Leçon de braise / La Peine Capitale, included in the portfolio Les Leçons, outlines a scene of complex interpretation, which scholar Pierre Borgue has read as a representation of the “castration of the male as a symbol of the fertility of the virgin,” but it could also be a female claim for independence, including sexual independence, against male supremacy. The drawings in Fêtes secrètes, of which there are two photolithographs, also illustrate the struggle between eros and thanatos, that is, between love and death, with dancing skeletons and hanging figures. These scenes of seduction and macabre dance, characterized by linear extenuations and formal sophistication, have been juxtaposed with the description of a feast in Vasari, but reinterpreted with Fini’s attention to physicality and theatricality. The artist uses a sign that alternates between lightness and nervousness, sometimes leaving the figures without defined contours, accentuating their phantasmal aspect.

The graphic corpus also includes examples of her prolific activity as an illustrator for others’ works, such as Les Petites Filles Modèles (1973) and Carmilla (1983). In the illustrations for the tale of the Countess of Ségur, Fini subverts the didactic tone of the original by focusing on the transgressive and flirtatious aspects of the young protagonists, who are often portrayed without panties, in order to expose their feigned innocence. As for Carmilla, the novel by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the donation includes two lithographs of imaginary heads. These effigies, floating in the emptiness of the paper, are in dialogue with the artist’s Visages imaginaires and recall ancient funerary art, particularly the portraits of El Fayyum. Finally, two lithographs referable to unpublished studies for the 1964 illustrated edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal are also on display.

The artist also distinguished herself as a multifaceted set and costume designer for the theater. In 1951, Fini participated in the Venice Biennale’s International Festival of Contemporary Music, signing set and costume design for Roberto Lupi’s one-act choreographic opera Orfeo. The work was successfully received and the set design was described as “metaphysical and mortuary,” dominated by a dark and mysterious forest where an enormous bucranium (ox skull) emerged reflected on the still water. An original set sketch for the play is on display in the exhibition, thanks to a collaboration with the Biennale’s Historical Archives of Contemporary Arts. The costumes were marked by simplicity and refinement, with recurring elements such as pheasant feathers attached to Orpheus’ ankles, which gave the dancing figure an appearance of extreme lightness.

This engagement in Venice in 1951 reinforced his international status, combining exhibition activity (the solo show at the Ala Napoleonica) with the creation of an enigmatic public image, culminating in his appearance at Don Carlos de Beistegui’s famous “Ball of the Century” dressed as a “Black Angel.” Her art, which knew no boundaries or categorization, continues to be celebrated for its magnetic force and its ability to explore the human enigma

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.