Entering a museum and being confronted with a nude no longer scandalizes anyone. On the contrary: the nude body, celebrated for centuries, is at the very heart of art history. Yet, just move a detail, make the image more explicit, more direct, closer to the language of pornography, and suddenly the wall of censorship rises. Why do we accept without blinking an unblinking eye a Renaissance Venus or a Mapplethorpe photograph, but react with annoyance or rejection in front of a performance showing real sexual acts? The question is not trivial. It concerns not only our relationship with art, but also the fine line that separates the aesthetic from the pornographic, the “noble” from the “obscene,” the acceptable from the forbidden.

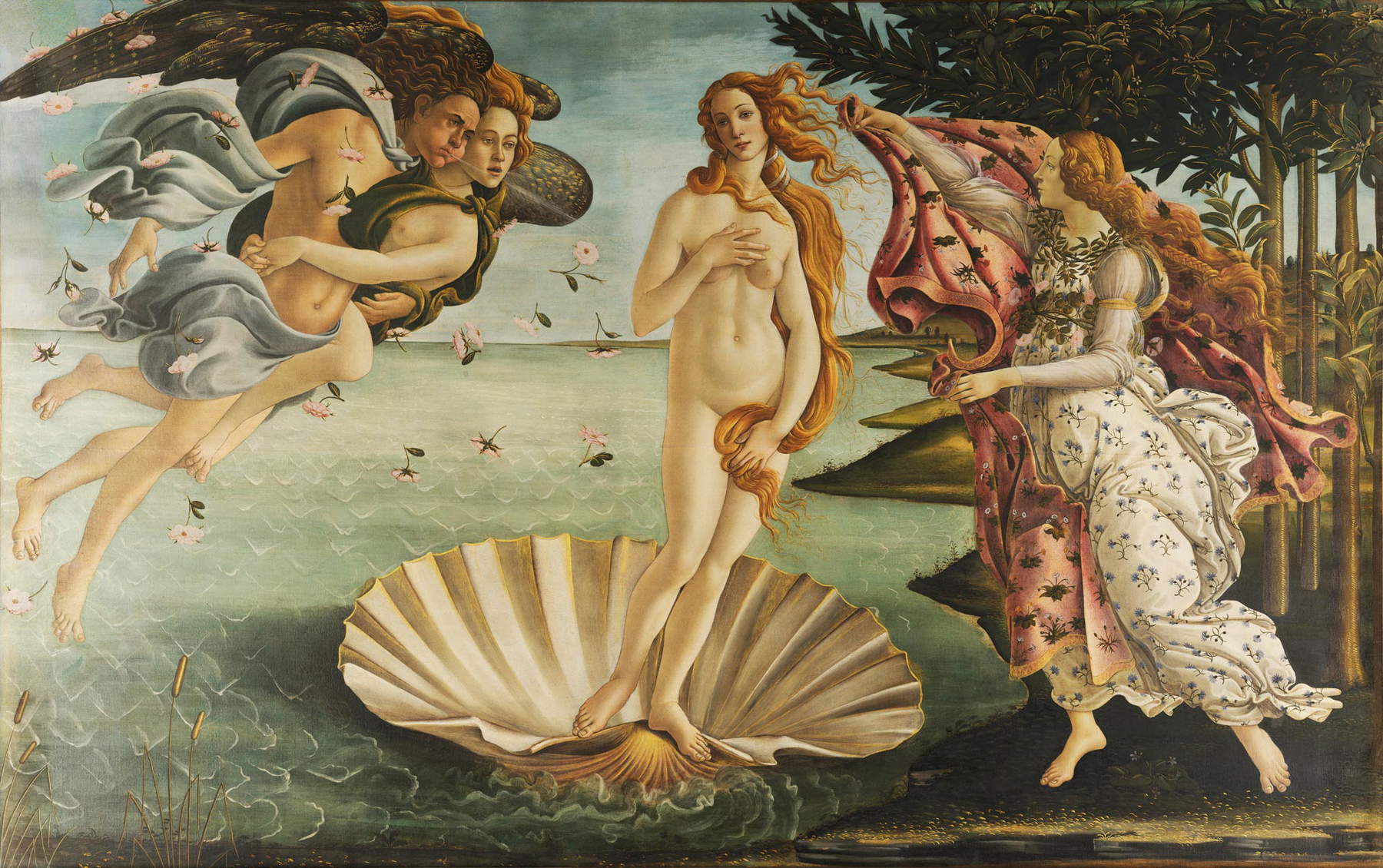

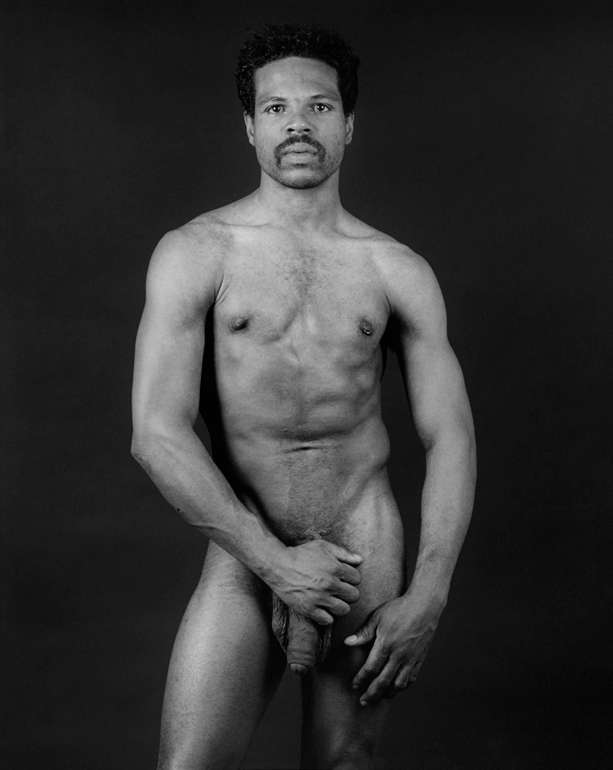

For centuries, the nude body has been exalted: from Greek marbles to Titian paintings to Egon Schiele. Yet the difference between “artistic nude” and “obscene” remains a minefield. Botticelli’s Venus can be displayed in schools; a contemporary photograph showing genitals in close-up, on the other hand, risks being blacked out on social media or banned from exhibition. And here the contradiction opens up: is it really just a matter of content? Or does the context matter? If the same image is in a museum, it is art; if it circulates online, it becomes pornography. It is not the body that changes: it is us.

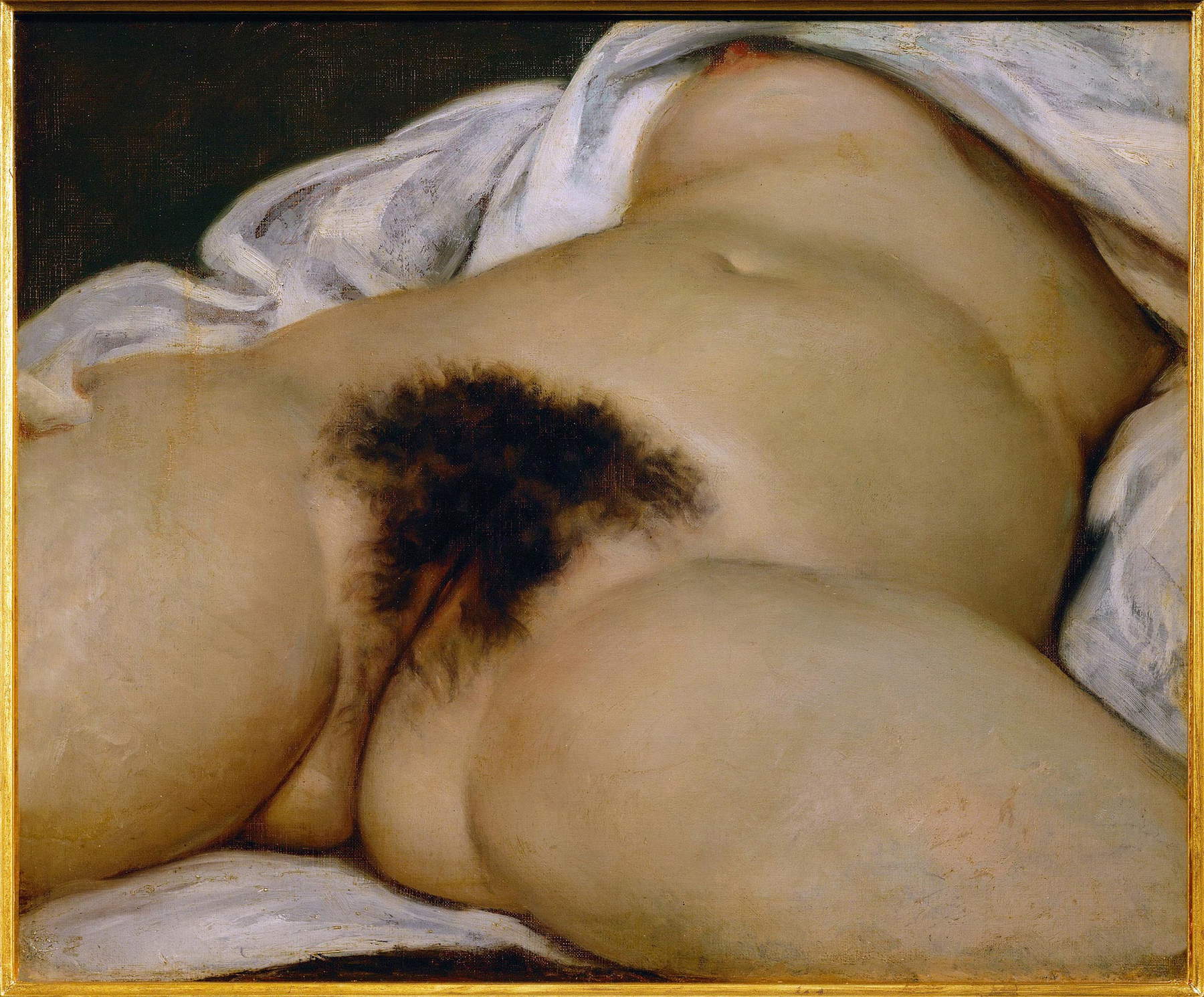

The distinction is often left to institutions, curators, ethics commissions, and even the algorithms of digital platforms. The result is that arbitrary criteria decide what deserves the space of culture and what does not. The very images we admire in museums today were, in the past, accused of indecency. We need only recall the case of Courbet and his Origine du monde: a work that in the 19th century was hidden from the eyes of the public and that even today, when it appears on social media, is automatically censored. So, the scandal is not intrinsic to the work: it is in the system that looks at it.

Many contemporary artists have decided to cross the border. Some work with pornographic actors, others stage real sexual acts, and still others play with theaesthetics of X-rated films to interrogate desire, power, commodification. In these cases, pornography is not a “theme” but a language: a way to break the barrier between what can and cannot be shown. But why then are certain works displayed in galleries, while others are rejected as “unworthy”? Could it be that the real difference lies not in the images, but in our willingness to look at them?

We live in a hypersexualized society, bombarded daily by erotic images in advertising, movies, television. Yet when sexuality enters the museum space, caution is triggered. There where marketing can play with half-naked bodies to sell perfume or cars, art still has to justify itself. It is a contradiction that smacks of hypocrisy. What’s more, censorship is never neutral: it especially affects bodies considered “uncomfortable.” The explicit female body, queer bodies, nonconforming bodies. What is disturbing is not just nudity, but its ability to challenge dominant models of desire.

If a museum exhibits an explicit work, it is not only making an aesthetic choice, but also a political one. It decides to give sex a cultural dignity, to remove it from pornographic language alone. If, on the other hand, it censors, it confirms the taboo. And then the question is no longer whether the work is art or pornography, but whether the museum has the courage to accept the challenge. It is easier to protect oneself behind the formula of “good taste” or “decorum,” but that is where it is decided whether art remains alive or merely reassures.

Social media, with their self-righteous algorithms, have brought sexual censorship back to the center: all it takes is one explicit nude photograph to trigger bans, shutdowns, flagging. In this context, museums sometimes seem timorous, almost complicit. But isn’t it art’s job to do what social media bans? To show what is removed, to give space to what embarrasses us? In the end, the question is not a technical one, but an ethical and political one: are we willing to acknowledge sex the same space we acknowledge pain, death, war? If we accept works that show bodies torn by violence, why not accept bodies that celebrate pleasure?

The answer to this question ignites a discussion that affects not only museums, but society as a whole: our relationship with the body, with desire, with freedom.

Art and pornography are not separate worlds, but languages that continually intersect. It is up to us to decide whether we welcome this contamination as an opportunity for reflection or reject it as a threat. The next time an explicit work is censored, we should ask ourselves: are we protecting the audience, or are we protecting our hypocrisy?

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.