Empoli, summer of 1925: a small room located at the end of a vegetable garden on Via Tripoli becomes the center of gravity for a new generation of creative artists and returns to us today the image not of a motionless and silent province, like the one that perhaps a traveler in the 1930s might have glimpsed from the window of a stationary train, but of a city capable of nurturing a generation of artists capable of elaborating an autonomous figurative language, in constant dialogue with the centers of national culture. This path, defined by Alessandro Parronchi as “a diffuse breath of figurative civilization,” has its roots in a physical and symbolic place: the little room in Via Tripoli.

This space, granted by his mason father to the young Mario Maestrelli (Empoli, 1911 - 1944), quickly became a place of experimentation where talent was refined through direct confrontation and constant practice. Together with Virgilio Carmignani (Empoli, 1909 - 1992), Maestrelli started a partnership that would mark the local figurative tradition for decades to come. The “stanzina” was not just a storehouse of tools and building materials, but an intellectual refuge where young artists discussed technique and new forms of representing reality. The original group was soon joined by other young people from the area, attracted by a climate of cultural fervor that sought to overcome the perception of Empoli as a quiet, immobile provincial town. Telling this story for the first time in an organic way is an exhibition, Provincia Novecento. Art in Empoli 1925-1960 (Nov. 8, 2025 to Feb. 15, 2026 in Empoli, Antico Ospedale San Giuseppe, curated by Belinda Bitossi, Marco Campigli, Cristina Gelli and David Parri).

The training of these artists did not remain confined within the city walls, but was nourished by the constant commuting to Florence. Train S.G. 4917 became the symbol of this openness to the world: students bound for the Porta Romana Art Institute took it every day, and in that school, which can be considered almost a kind of workshop, the young Empolians learned their craft under the guidance of masters such as Libero Andreotti and Giuseppe Lunardi, living a didactic experience that aimed to reduce the distance between the applied arts and the major arts. The Florentine environment offered them the opportunity to immerse themselves in the theoretical discussions that animated the tables of historic cafes and the pages of the art magazines of the time. Guys like Cafiero Tuti, Ghino Baragatti, Loris Fucini and Amleto Rossi learned not only the technical craft, but also the urgency of a poetic quest that overcame academicism: the cultural atmosphere of the time was dominated by the attempt to break out of the perimeter of Crocian idealism, and they sought a new expressive naturalness that would find legitimacy in the avant-garde magazines of the period. “The cultural atmosphere, lively for practical examples, theoretical reflections and those exhibition occasions favored by the regime in order to shape a national figurative koiné,” scholar David Parri has written, “would be insufficient, however, to explain the particular artistic flowering of the time in the city if one did not take into account the fundamental alumnuship that many Empolese boys carried out at Porta Romana. And let us add at once, holding firmly to the logical thread we are following, that in the Florentine school, too, positions rather critical of the Crocian aristocratism were spreading. If the professionalizing orientation that characterized it can explain this aspect, that same course of training did not inhibit the professors from bringing into the classrooms, with the technical skills of their own discipline, also the ideas and concepts fermented in conversations born between the tables of the Giubbe rosse and the Paszkowski, giving rise to an intellectually fertile environment in which the theoretical discussions that found space in some periodicals of the time also fell.”

The figurative culture of Tuscany in those years oscillated between the recovery of the great tradition of the 15th century and the suggestions of a return to order. Artists such as Ardengo Soffici (Rignano sull’Arno, 1879 - Forte dei Marmi, 1964) represented an inescapable point of reference, especially for their ability to combine the lyricism of nature with the solidity of simple forms. One of the group’s artists, Sineo Gemignani (Livorno, 1917 - Empoli, 1973), recalled how, during Sundays spent together, the young Empolians recited entire passages from Soffici’s essays, absorbing his lessons on expressive sincerity. But there was room for other points of reference as well: alongside the learned models, an eccentric figure like Dante Vincelle (Florence, 1884 - 1951), a self-taught painter from the world of glassworks, known for his primitivist style and use of vivid colors, operated in Empoli. Nello Alessandrini (Empoli, 1885 - 1951), too, with his academic training and interest in the rural everyday, offered younger people an example of dedication to teaching and en plein air painting. The aesthetics of the stanzina group, moreover, were not isolated from Florentine intellectual currents. Many of the artists frequented literary cafes, where theoretical discussions fueled their daily practice. Magazines such as Mino Maccari’s Il Selvaggio and Solaria offered a ground for discussion of such themes as autobiography and the rediscovery of natural reality. Cafiero Tuti (Empoli, 1907 - 1958), in particular, was among the first to collaborate actively with Maccari, bringing to his woodcuts a Tuscan spirit balanced between Giotto’s lesson and contemporary anxieties. Ghino Baragatti (Empoli, 1910 - Milan, 1991), nicknamed the painter-mechanic, also frequented Soffici’s house in Poggio a Caiano, and developed a style that combined the severity of peasant atmospheres with a pulsating, spiritual pictorial material.

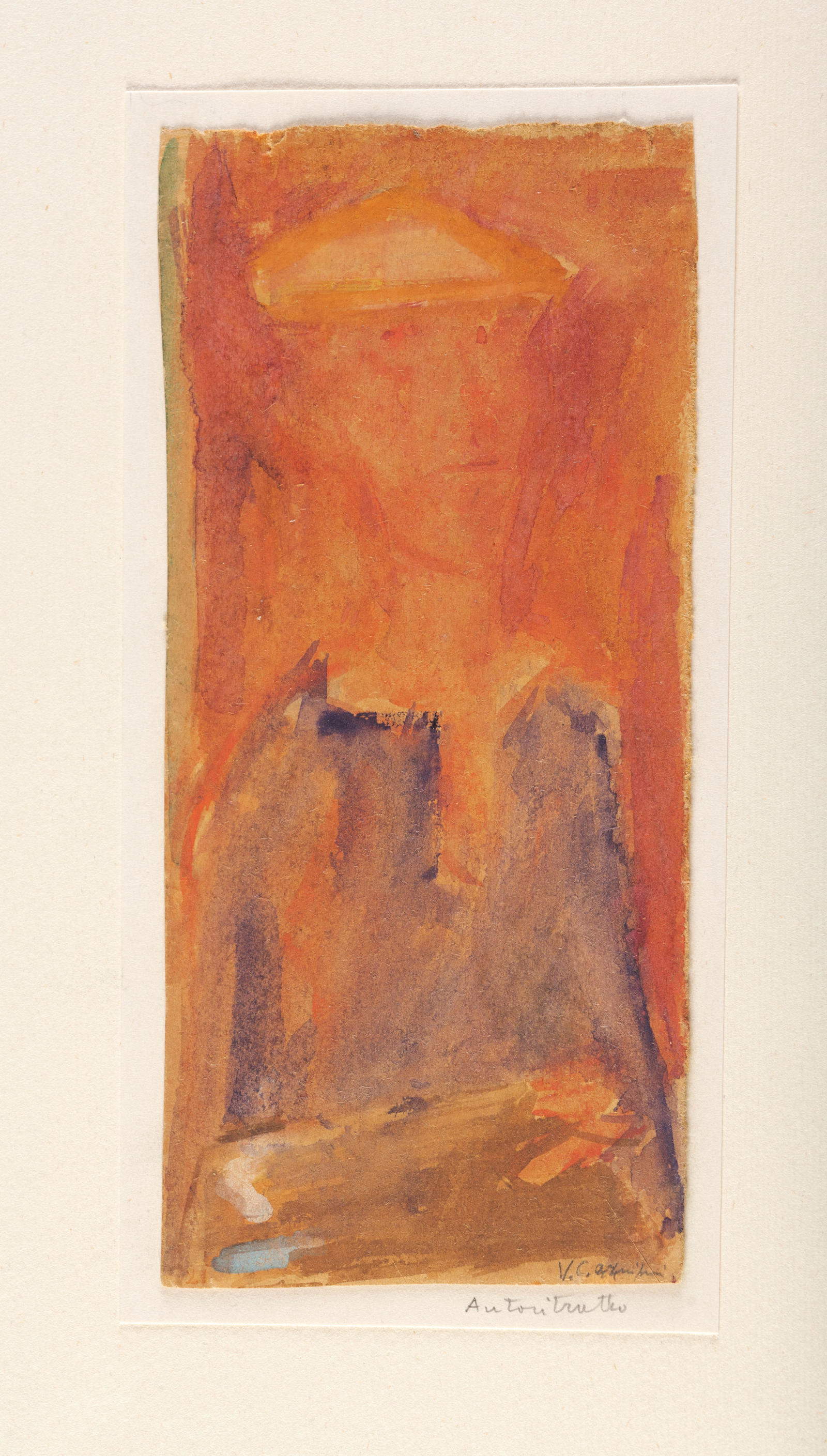

In the 1930s, the stanzina group would reach full maturity, beginning to be noticed in exhibition contexts of national importance. The circondarial exhibitions organized in Empoli became occasions to measure the progress of authors such as Cafiero Tuti, Amleto Rossi (Empoli, 1911 - 1969) and Ghino Baragatti. In this period, thefresco technique assumed a central role, perceived as the most suitable language for expressing a new monumentality. Sineo Gemignani, in particular, one of the youngest of the group, emerged as a precocious talent, obtaining prestigious commissions such as the decoration of the G.I.L. House in Florence. However, despite their successes, many of these artists continued to experience painting as a strenuous vocation, often alongside menial professions orteaching in technical schools. The search for artistic identity passed through the psychological introspection of self-portraits and the depiction of a sorrowful and silent humanity.

The outbreak of World War II marked a dramatic rupture in the lives and careers of all the protagonists. The forced diaspora took many of them far from Empoli, to the combat fronts or prison camps. Virgilio Carmignani lived the experience of military internees in Germany and Poland, where drawing became a tool of psychological survival. Using makeshift materials such as cigarette papers and brick dust, Carmignani documented the suffocated suffering of the barracks, preserving his own human integrity through the act of creation. In Italy, other artists chose the path of active participation in the liberation struggle. Enzo Faraoni (Santo Stefano Magra, 1920 - Impruneta, 2017) and Gino Terreni (Empoli, 1925 - 2015) joined the partisan brigades, experiencing firsthand the trauma of the civil war. Faraoni was among the protagonists of the bombing of the train loaded with explosives at Poggio alla Malva, a sabotage action that cost him serious injuries and the loss of dear friends. Even in hiding, art was never entirely abandoned, although he changed his register to more rugged and expressionist forms. Ottone Rosai, while maintaining an ambiguous public façade, offered refuge and protection to many young artists involved in the Resistance, profoundly influencing their ethical vision of painting-making. Mario Maestrelli, in an attempt to avoid enlistment, chose the path of isolation and simulated mental disorders, continuing to paint in secret until his tragic death in July 1944, when he was killed in a field just outside Empoli, most likely by a sniper. His body was recognized only after several days thanks to a set of keys. Before he died, on a break from his work as a mason, Maestrelli, Belinda Bitossi recounts in the exhibition catalog Provincia Novecento. Art in Empoli 1925-1960, had left a message traced in charcoal on a wall of the church of Santo Stefano degli Agostiniani: “art will have to resurrect in Empoli.” This wish became the moral testament for the survivors who, in the aftermath of liberation, found themselves in a heavily damaged city.

The postwar period in Empoli was marked by the urgency of reconstruction, not only material but also cultural. In 1946, a group exhibition at the Municipal Library attempted to reconnect the threads of the interrupted discourse, paying tribute to Maestrelli’s memory and presenting the works of survivors. Artists such as Sineo Gemignani and Virgilio Carmignani were called upon to collaborate on the rebuilding of damaged buildings, as in the case of the ceiling of the Collegiate Church of Sant’Andrea. The painting of this period gradually shifted toward social realism, with a focus on the world of labor and the dignity of the working classes. Gemignani, in particular, became a leading exponent of this trend, celebrating master glassmakers and flameworkers in works that combined formal rigor and civic engagement.

At the same time, some members of the group began to seek new paths away from Tuscany. Ghino Baragatti and Loris Fucini settled in Milan, inserting themselves into the lively artistic debate of the Lombard capital. While Baragatti continued to cultivate the tradition of fresco painting with monumental works for theaters and villas, Fucini opened up to the suggestions of the international avant-garde, approaching an abstractionism based on intense color fields. In Empoli, too, new figures such as Piero Gambassi (Empoli, 1912 - 2011) and Luigi Boni (Empoli, 1904 - Castelfiorentino, 1977) began to disrupt the canons of traditional figuration. Boni, after long sojourns in Paris and Chicago, brought an informal and material language to the city, using unusual materials for his abstract compositions. Gambassi, trained in humanistic studies, became an animator of abstract research in Florence, collaborating with the circle of Fiamma Vigo. Pietro Tognetti (San Miniato, 1912 - Empoli, 2003), after a long career as a ceramic modeler, also converted to abstract forms in later life. Loris Fucini (Empoli, 1911 - 1981), who moved to Milan, gradually abandoned traditional figuration to open up to bright colors and dreamlike compositions influenced by the European avant-garde.

The postwar period also saw the emergence of Sineo Gemignani and Renzo Grazzini (Florence, 1912 - 1990) as exponents of a realism of deep civic commitment. Gemignani, influenced by the Milanese climate of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti but faithful to his Tuscan roots, developed a monumental and archaizing language. His works of the 1950s, such as the Vetraio and the Fiascaia, became icons of the celebration of the working world. His consistency led him to reject the conditioning of commercial galleries, preferring a provincial dimension that guaranteed free and authentic research. Renzo Grazzini, for his part, exalted neighborhood life and social reconstruction through a painting that placed man at the center of all truth.

The transition from the 1940s to the 1950s thus marked the definitive divergence of the artistic paths born in the little room on Via Tripoli. While fidelity to a realism based on love for man and possession of the craft persisted, instances of rupture emerged that looked to the future with universal languages. The Empolese province, far from being a closed environment, had shown itself capable of generating original responses to the tensions of the short century, oscillating between the lyricism of youth and the stark reality of history. The memory of those difficult years remained etched in the works of Gino Terreni, who never stopped recounting the epic of the Resistance through woodcuts with a dry, angular stroke.

The artistic experience in Empoli between 1925 and the postwar period represents a significant chapter in 20th-century Tuscan culture. That generation of painters, who grew up amid economic hardships and the dramas of the war, knew how to transform their existential condition into a figurative testimony of rare intensity. From the first common experiments to the solitary choices of maturity, their path reflects the contradictions and hopes of an era of profound transformations. Today, the recovery of these authors and their contexts makes it possible to reactivate a collective memory that recognizes art as a fundamental tool of historical awareness and civic education. Their legacy, which from the mud of the trenches and the dust of construction sites reached the great public commissions of the 1950s, continues to tell the story of a generation that believed in the value and ethical commitment of making art. The experience of Via Tripoli, which began as a teenage game in a vegetable garden, has thus become an indispensable chapter in the figurative civilization of twentieth-century Tuscany.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.