What would happen if today, as they did in ancient Greece with sculptures placed in shrines and public spaces, suddenly and for different reasons works were removed because they hindered movement and circulation? Imagine if, as they did then, the authorities in charge intervened with periodic thinning and precise regulations on the use of public space. Who knows how many monuments would disappear. And on what outlandish, probably anti-historical grounds. It is not surprising then that even a civilization as attentive to beauty and decorum as that of the Roman Empire had in use the practice of damnatio memoriae; after all, an always topical subject this, as we see also in Italy something similar is happening with the so-called cancel culture: the reception of images has always created oppositions between adoring worship and the will to destruction.

In Calabria, on the other hand, there is the case of a sculptor whose works, for causes very distant from those of ancient Greece and the Roman Empire and far from the idea of the culture of removal, nevertheless “disappeared.” These works, truly extraordinary and numerous, remained guarded but little accessible in the house-workshop after the artist’s death in 2012. And concentrated, to tell the truth, in a small space and moreover private, therefore practically almost invisible. On the occasion of the centenary of his birth, several hypotheses are being put forward: for example, moving the sculptures elsewhere, to a public space, so that they can have more visibility and be rediscovered by the community. Could this be a supportable and even viable idea? And how to succeed in resurrecting this forgotten sculptor and his works without betraying their place of origin? Before answering, though, let us take a step back. Who are we talking about? Who is this sculptor? Here is his story.

Not many years ago, there lived in Calabria a skilled “craftsman” who knew how to “force” his skilled hands between clay and hard stones, bronze and marble, to give form and substance to sculptural material. His name was Joseph Correale and he sculpted time with his hands, shaping it to his liking. He was an artist extraordinarily capable of synthesizing the essence of sculpture in different configurations, from busts to crucifixes and motherhoods, from dancers to variations of forms in space, with results that were surprising to say the least but never recognized enough.

Critics of the temperament of Achille Bonito Oliva and Marcello Venturoli and Calabrian scholars such as Sharo Gambino, Luigi Vento, Carlo Pascale and Salvatore Santagata have related his works to the “superstars” of Italian sculpture such as Michelangelo, Pollaiolo and Manzù, but without neglecting his master Annigoni in drawing, and have even compared them to those of some foreign greats: Degas, Giacometti, Rodin and his follower Maillol, Brancusi, Arp, Moore. All the more reason, then, for this year’s centennial, it would be necessary to make Correale and the sophistication of his excellent work known. And to do so means not only to acknowledge once and for all that he was an unrepeatable sculptor, especially in relation to the effort it took him to persevere and overcome every obstacle, but also to ask a series of questions as to why despite his talent, consideration of his worth has not remained intact over time and why it is only now that we are thinking of highlighting it. How did we forget Correale?

Let’s start at the beginning, going to learn more about this master of the second half of the twentieth century, briefly tracing his biography, first asking what kind of path he went through to build his sculptures. Where did he gather ideas? What was his creative proceeding? What world did he see to then create his own, in spite of the adversities of his place of origin, Calabria, and moreover of the era in which he happened to live? Let us try to focus more closely on Correale’s story in order to get inside the work of a master who absolutely must be reevaluated.

Joseph Correale (Siderno, 1925 - 2012) is barely a boy when, living in a reality divided between cultural backwardness and skepticism toward artistic professions, he takes his first steps in perhaps the most complex discipline, sculpture. He is deaf to other reasons, his hands flitting between drawing sheets and molds, putti... that he makes from simple clay. The first works he looks at with interest are mainly religious (the plaster casts by his will are collected in the Diocesan Museum of Gerace), still preserved in those churches in the area near Siderno that from Canolo to San Luca to Polsi and Siderno Superiore would later be embellished by his own crucifixes, statues of saints and Madonnas with Child.

The youthful years in which he lived in Siderno were very difficult: hunger, war, the fascist regime. In spite of this, the need to invent matter, to “give birth to the world” began to arise in him, elaborating a plastic and conceptual research that at first sprang from the scraps of clay recovered from the nearby kiln in his small town. Over time, his working method and his rather erratic research advance, especially from the moment he joins a carpenter’s workshop where funeral caskets are also carved.

In addition to the objective difficulties, there is that of the family, which is of humble origins. His father Francesco, a coachman, does not stand in his way; his mother Vittoria Gozzi, an embroiderer, on the other hand, is perplexed (“contrite but resigned,” argued scholar Meduri, “like the Virgin carved in bas-relief in the Via Crucis of Polsi”) by what she glimpses making its way. Adolescence passes in a flash and we are already at the turn of World War II, in 1943, when among the ruins of a razed building, barely 17 years old, he retrieves a wooden board. It is the beginning of something, the spark of a shining future. The result he makes from the scraps of that bombed-out house is astonishing; out of it comes a bas-relief depicting the Trinity, a work that will be so admired that it will be requested to be displayed in the window of a jewelry store. Along with this, in the same years he made a fine wooden statue (in poplar) the so-called Madonna of Peace, in Baroque style, named after the signing of the Armistice in 1943. It is still kept in the church of Santa Maria dell’Arco in Siderno and has a very important value for the community, because it was paid for by the women of Siderno with a subscription amounting to 16 thousand liras (about 6 thousand euros today). Before long, things would begin to change quickly, because a Florentine clergyman, Isnardo Bologni, visiting the city, noticed his artistic talents, prompting the boy to move to Florence. Then, from 1949, moved by his curiosity, he will go to America, pursuing a dream that will be possible to realize only thanks to the hospitality given by an uncle.

It must be said that if Correale’s sculptures are the product of a miraculous weave made of talent and stubbornness, gifts that the young man did not lack, over time he has been able to “guard” them with care especially since he decided to “repair” in silent recollection in his homeland. His work is extraordinary first and foremost because it has been distinguished by a resolute obstinacy not to give in to the compromises of the market, even when the demands for gallery exhibitions came from the main art venues. This was the only way it could happen that those who entered the kaleidoscopic universe of his workshop, as many did, began to get lost among the “words” of those marble or terracotta faces, wandering among patches offresh clay, surrounded everywhere by chisels, gradine, subbie... Correale is in the dust of marble or stone that he preferred to sink his hands, to feel with touch every impalpable texture.

In fact, the sculptor will soon return to Calabria. He returns there, as we said, after several years spent between Florence, which for his artistic training was the first great teacher, where he attended the Free School of Nude with great artists such as the painter Pietro Annigoni and the sculptor Corrado Vigni. Here he tried his hand deepening his use of clay to make his first real terracotta works. He would later fly to New York, in 1949 (a stay soon interrupted because he would be reported for illegal immigration and then repatriated), then in 1953 and 1969, periods when America exploded with Abstract Expressionism and later with Pop Art. In the U.S. land he made several design sculptures for city storefronts, and this was a determining factor because it enabled him to continue his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts and then to broaden his skills at the Art Students League in Manhattan even with the opportunity to work with models.

When, as if to come full circle, he returned home in 1971, the place where it all began, with his wife Mary Josephine Proto (whom he married in 1963 and by whom he would have three children who cared for and cherished the delicate legacy), the artist was just under fifty years old. It is not an easy return; Calabria is a land that “burns” in “slow time,” “stagnates” in a dimension of indolent slowness, an element, however, that favors the sculptor’s plastic meditation. Nevertheless, taking root again in the South is a hard-fought choice, because detaching himself from the most vibrant artistic circles in the world puts him in crisis. From a certain moment on, however, to prevail, over that of the market, is an option of pure poetic research. New York will thus be the metropolis he will leave without delay, just when he realizes that for too long his activity, however prolific and remunerative, had been “dangerously” veering toward a more commercial than purely artistic aspect, and this was not acceptable, not akin to his way of conceiving sculpture and life itself. In this regard, Correale, who was a generous man and artist who often donated many of his works, knew the value of things: more than once - his son Francesco tells us - when faced with unexpected offers for some of his sculptures that were not for sale, he “resisted,” he did not allow money to dictate, he did not allow it to buy his ethics and the poetic delicacy of his work.

His silent and tireless sculptural research never follows the same direction: it is as if the artist was traversed by a thousand intuitions and wanted to continually experiment, to always reach perfection, to try to penetrate the secrets by which a material takes shape; in fact, he meditated on making a way of sculpting that was devoted to Michelangelo but also discovered the mysteries of the human heart, “to sing them, to make them spatial forms.” a personal poetics of sculpture that from the exaltation of the human figure, to the religious afflatus, would in time become, as in fact it did, also an instance of heated social scrutiny.

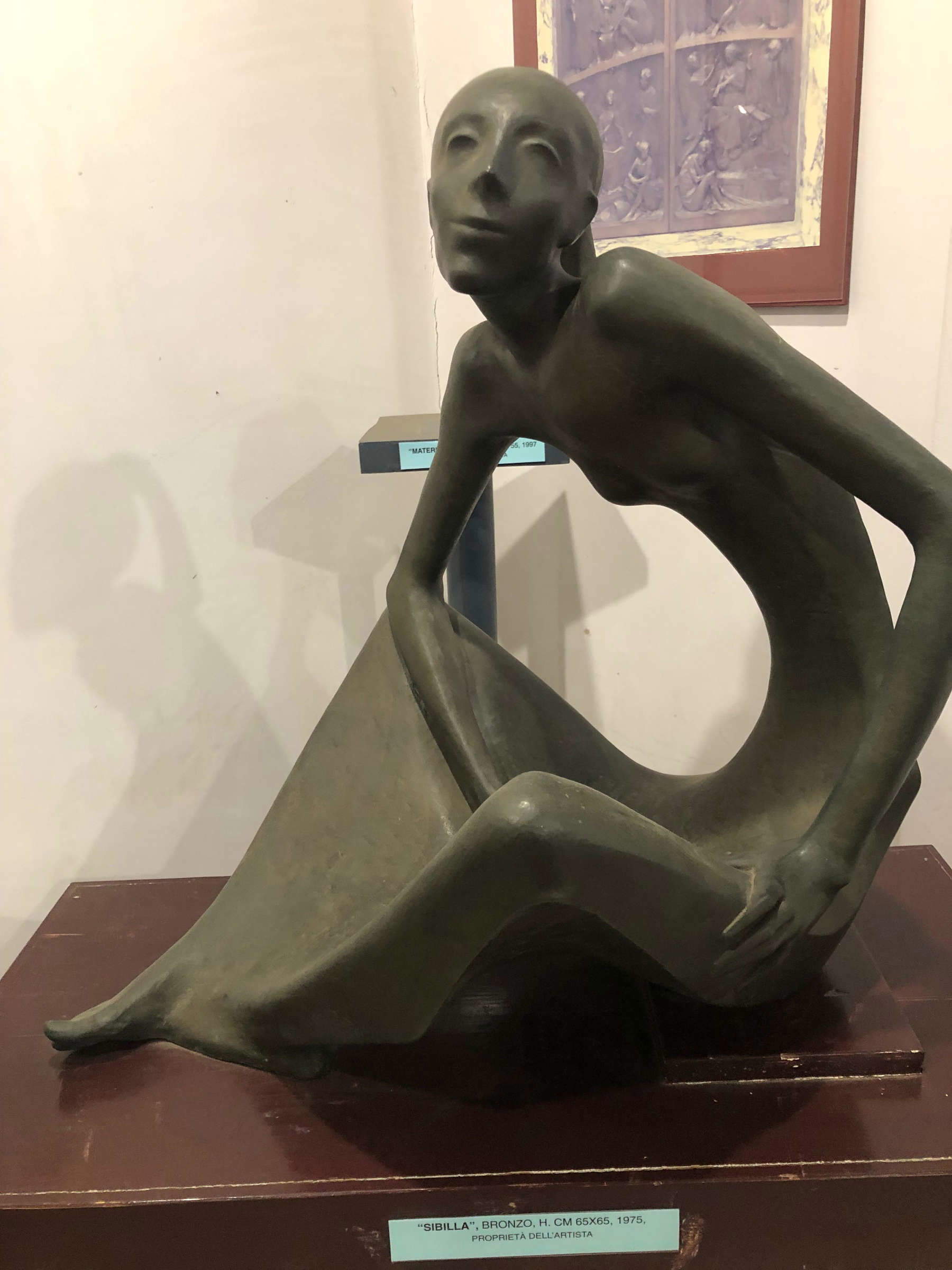

We were talking about how over the years his work was paralleled with that of Manzù or Moore, Giacometti and Jean Arp, but there would be other comparisons to be made as well, for example with Schiele in the way he understood the thinness of the bas-reliefs of the Via Crucis, and, again with the Sanctuary of Polsi in mind, one can even compare him with medieval wooden sculpture, particularly German sculpture with its dry, angular and nonetheless dramatic lines. On other sides, for example, for the figuration of the Deposition, Niccolò dell’Arca’s Lamentation of the Dead Christ also comes to mind. But looking at these juxtapositions more closely, Joseph Correale’s sculptures could also be framed thematically, not just by periods or seasons, and in this way the approaches to Alberto Giacometti, to his fascination with Etruscan forms, for example, would be more stringent and actually more evident. Let us observe, to get an idea, how Correale’s sculptural lines taper off when he constructs the threadlike bronzes of the Deposition or the Outcasts, or those of theAcrobat and the Contortion. Many are the emaciated faces in Giacometti as in Correale. Reduced to an almost larval state as a trove of images of the dramatic consequences of war.

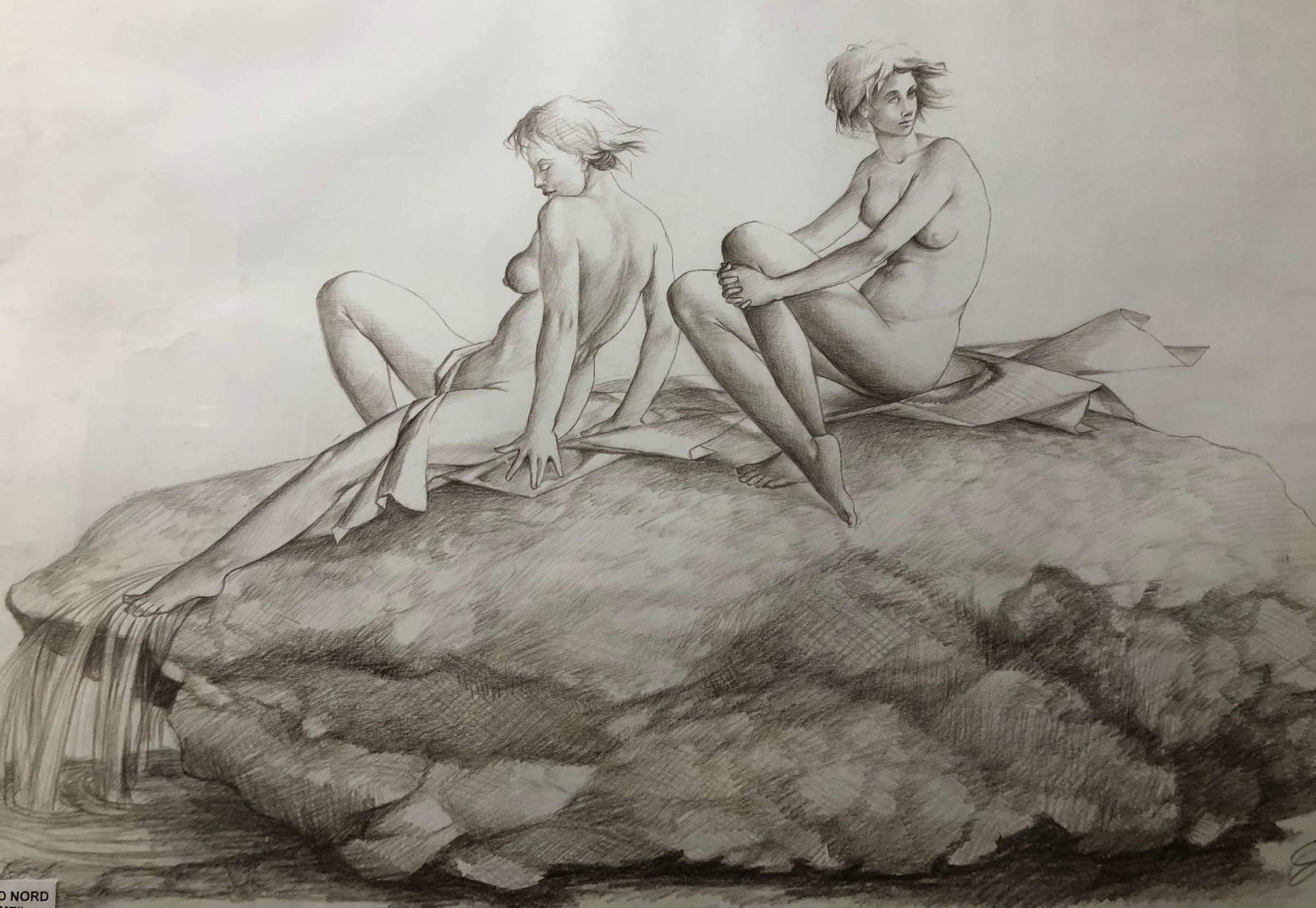

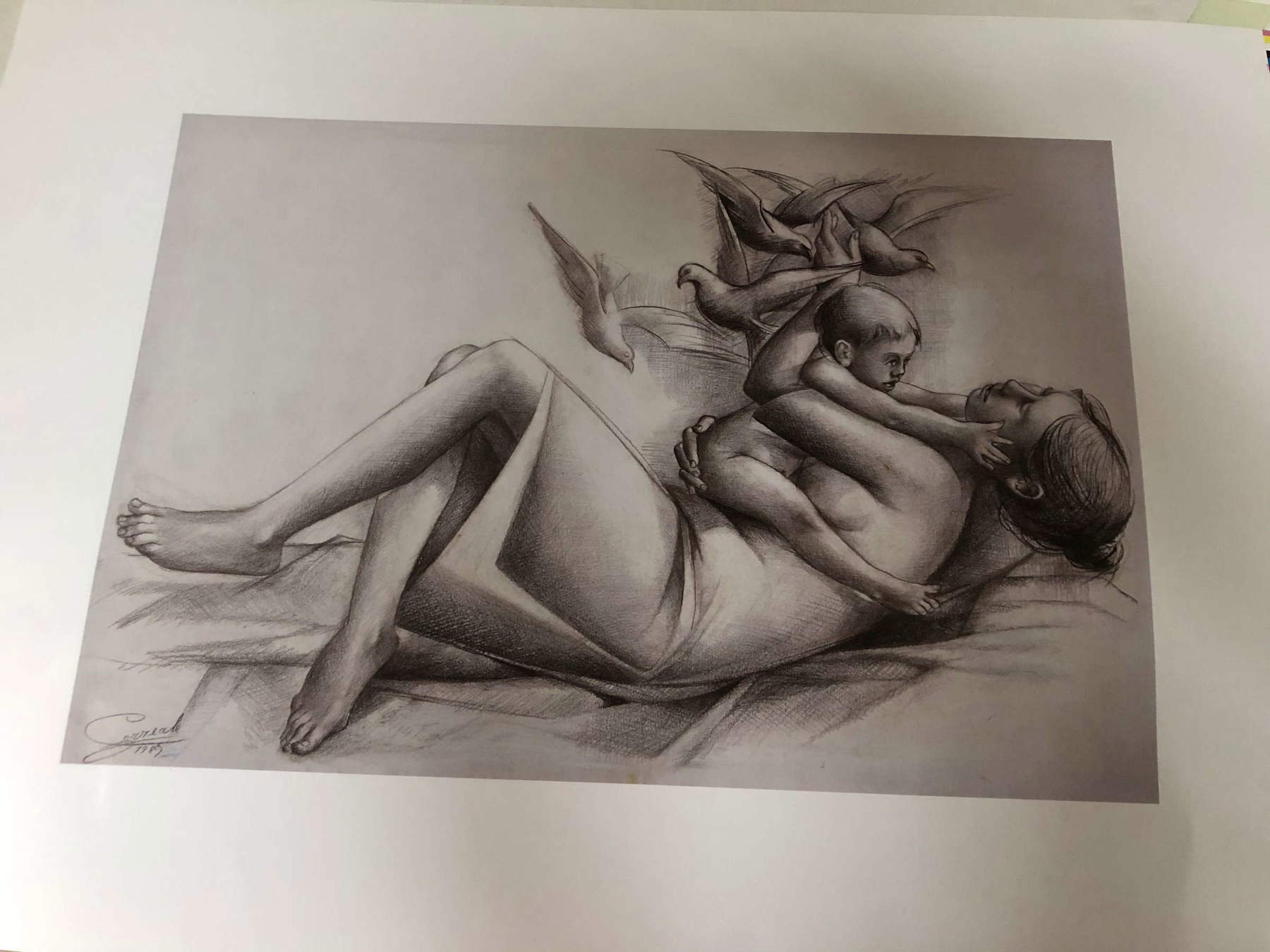

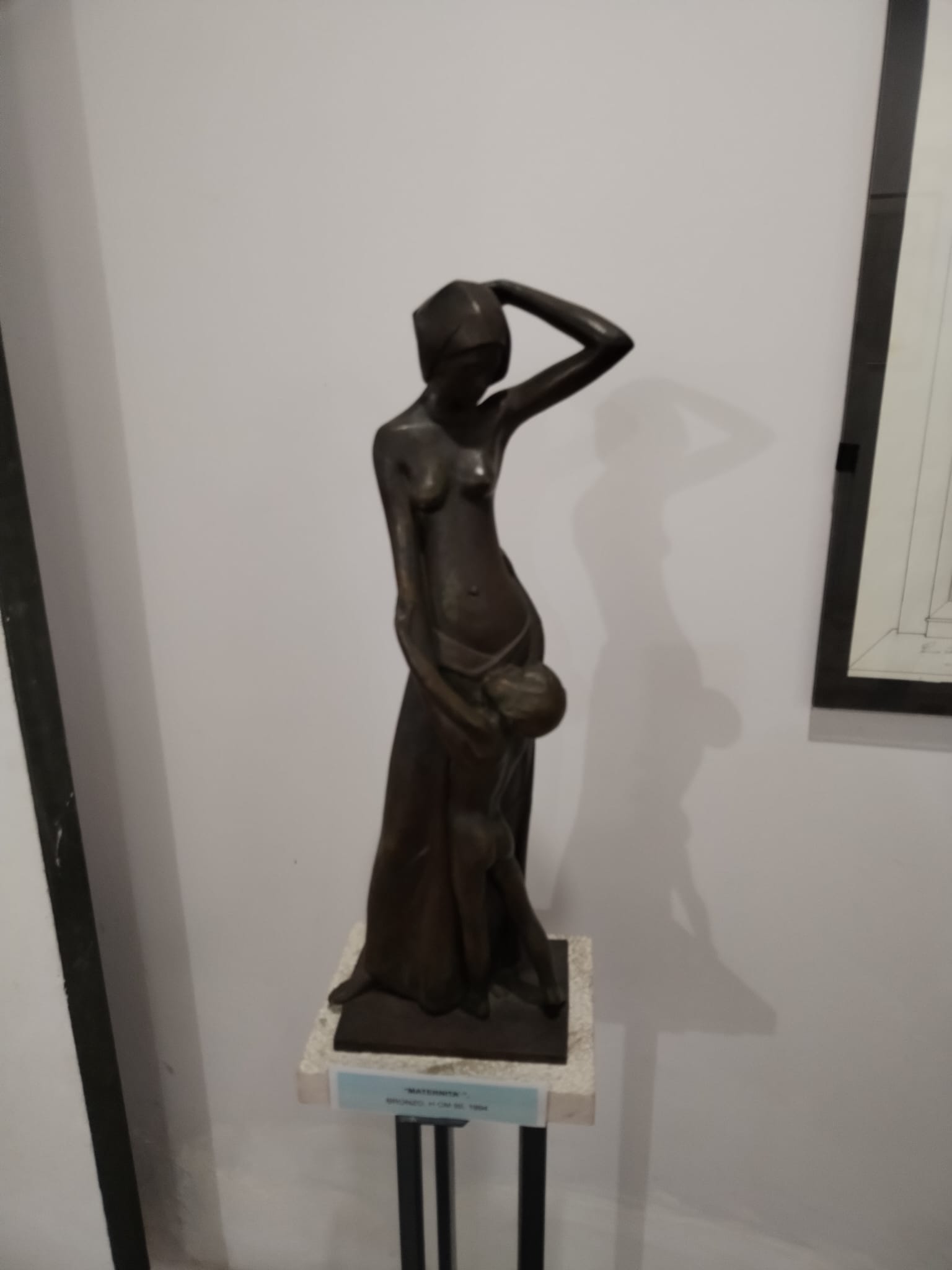

The sculptor’s language, however, remains that of “his time, his people, his places and his history” (Caterina Meduri, Joseph Correale. The Forms of a Faith, Iiriti, 2024). A mother tongue that in the sculptural rendering of the forms it expresses becomes more and more human. Let us always put in question the Polsi panels where, from station to station, the faces from thin and angular become softer and softer, ending in the ephebic and almost androgynous bronze of the Risen Christ. But there are many forms on which Correale’s attentive gaze has fallen: there are the modules of the Ballerinas, airy fluttering forms of travertine or bronze; there are the many Maternities, with ever-changing lines that sometimes even turn into symbols of Japanese culture, real “ideograms” of stone (M. Venturoli, Il giornale di Siderno e della Locride, 1999). They are not always docile Mothers who welcome their children into their wombs: Correale’s are strict women who accustom their children to the complexity of life. And it is exactly in this choice - according to Sharo Gambino - that the popular character of Correale’s sculpture and soul is revealed. The writer and scholar from Serra San Bruno recounts this in an article written in 1978 where he recalls the amazement he felt on his first visit to the Sidernese studio.

Eclectic in style, in the sense that “he can treat stone as easily as plaster, wood as well as marble and bronze” (Luigi Vento, Joseph Correale Scultore, 2008), but popular in taste, Correale prefers to sculpt the most fragile creatures, the “vanquished,” such as the stricken Boxer; his is a realist sculpture especially in that of portraits. But beyond all that, his sculptures transport away from the factual datum thanks to a sublimity that makes the poses aerial and sulfurous, the forms elongated, expressive, and essential, all sculptural acrobatics that, despite the weight of the material, hymn to lightness, the ephemeral, and hold the stone back from the reality of finiteness: there is more emptiness than fullness, in many works the concave and convex dimensions often converge, as does the unfinished, which far from being crude in workmanship, is expressed in a deliberately gestural, faster outcome.

The studies that should be undertaken to understand Joseph Correale’s work more fully are many, and this contribution is only a stone thrown into the pond whose effects, its concentric circles, we would like to see propagated producing significant changes for a greater sensitivity of the Locridean territory on one of its most brilliant sons. One inquiry to be made, for example, is about the materials he used; Correale always selected them differently. Sometimes preferring rare materials such as pink and cloudy marble from Portugal, other times choosing stones he found along the rivers, then there is verdite, granite or travertine but also extra-sculptural materials.

Another study that should be done (and which we have only hypothesized here) is that of the social and intellectual humus of the area. The sojourns in Florence and America were fundamental to his path as an artist, but in addition to a study to document those years, the circumstances under which the artist found himself working in Calabria should also be studied, what language his city “spoke” in those years, who were, if any, the artists contemporary to him: it would be important to understand what works he may have seen or known. Who did he frequent? We know that near his workshop was the “famous” Gentile bookstore where many intellectuals of the time gathered. My “well-rounded” investigation of Joseph Correale is also meant to document the atmosphere, which many people say was rarefied, that one could breathe in that place, the air that was in the air, who one could meet upon entering it.

The idea behind this article, and which I believe can be the foundation of any future initiative, is to rethink Correale as a fundamental sculptor of Italian art, to imagine him occupying the place he deserves in the Italian artistic repertoire, both because the’occasion of the centenary, which reminds us of the scope of his immense work, is not wasted, and also so that his works, the sculptural groups, can finally be seen within a museum created ad hoc, the “Correale Museum,” or better yet, set up in a “House of Correale Sculpture.” We think that a worthy location such as a museum could be the result of a careful work of critical reconnaissance of his work and a reconstruction and cataloguing of his works, but also a propulsive meeting place for scholars and sculpture enthusiasts, as well as a peculiar exhibition venue. A place, in short, that can house a significant part of the sculptures, that between exteriors and interiors, as does, for example, the museum of Marguerite and Jean Arp in the Ticino, can offer an adequate, more usable tour. A space halfway between public and private, where the heirs can always keep taut the thread that binds them to their father and through which, at the same time, together with the incunabulum place in Via Romeo, they can more easily make him known and allow his value to finally “deflagrate” in the Italian and international artistic galaxy. It should be an operation, this, capable of not betraying the feeling of intimacy that was proper to the workshop where many works were born, like a miracle. Not a forced displacement then but a gift to the territory, to the whole community. Because, in fact, one wonders if among the most plausible reasons why Correale’s sculptures today are “removed” from memory, completely forgotten, there is precisely the current exhibition space that, although cared for and made available by his sons, may, in part, have had a considerable weight in this. A place of the soul where those same sculptures have remained forever “nailed” in the eyes of those who have seen them: the mute workshop of Joseph Correale, the place where even he, tireless creator of beauty, was forced into immobility in recent years.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.