In recent times, there has been a keen interest in the art of Leonora Carrington (1917 - 2011), an interesting Surrealist painter who passed away in 2011, at the age of ninety-four: just think of the exhibition that the Tate Liverpool dedicated to her earlier this year, as part of the Mexico-United Kingdom 2015 event celebrations (the artist was in fact English and spent most of her life in Mexico). And what fascinates admirers of Leonora Carrington, in addition to her art, is her tumultuous biographical story, which has been recounted in books, essays, and articles in a variety of newspapers and magazines.

It is especially her love affair with another great Surrealist painter, Max Ernst (1891 - 1976), that is considered worthy of a novel. It was an almost dazzling encounter, which took place in the summer of 1937: for Leonora, the somewhat rebellious daughter of a wealthy industrialist family and a dreamy girl with a great passion for art, the opportunity to visit the exhibition of the Surrealists, which was being held that very year in London, could not be wasted. “I fell in love with Max’s paintings before I fell in love with him,” Leonora would later say: and indeed she met the German artist shortly after visiting the exhibition, at a party. They were divided by their age (Max Ernst was a good twenty-six years older), by their origins, and also by their romantic situation, because Max was married: however, all these differences did not prevent the two artists from falling in love immediately.

|

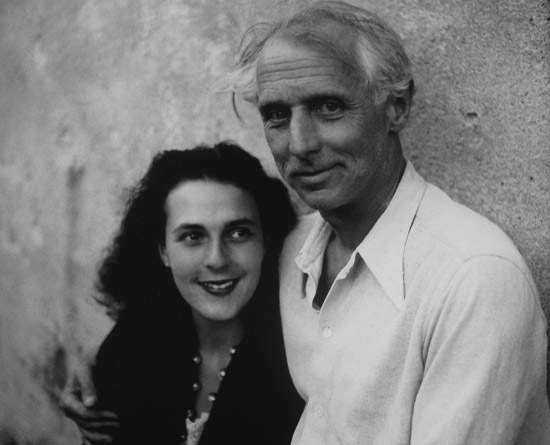

| Lee Miller, Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst (1939; Miller Archive) |

The two moved to Paris, mainly to find a greater sense of freedom and a more fervent cultural climate than in London. And Paris could give them what they were looking for: Leonora and Max began to associate with the likes of André Breton, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, and Man Ray. But soon even the atmosphere of the big city began to be unsuitable for the couple: Leonora and Max began to long for absolute tranquility, serenity, and distance from hectic city life. So they moved south to Saint-Martin d’Ardèche, where they bought a country house: Max decorated it with frescoes and sculptures, while Leonora delighted in her beloved painting. The days passed between walks, visits from friends in London and Paris, conversations about art and literature.Leonora would tell an interview with the Guardian in 2007 (and conducted, moreover, by her distant relative, journalist Joanna Moorhead) that everything she learned, she learned from Max. And this was despite the fact that Leonora had been trained to a high standard, in the best academies, and with even a sojourn in Florence: Max, besides being her lover, was also her beacon, her main artistic and cultural reference point.

|

| Leonora Carrington, Portrait of Max Ernst (1939; private collection) |

But just a few months later, in May 1940, Max was again captured on suspicion, without foundation, of being in communication with the enemies: he was still imprisoned, and Leonora’s mental stability began to be affected by the events the couple was undergoing. Max managed to leave the camp, but when he returned home, he did not find the girl: in fact, together with some friends, she had traveled to Spain, hoping to obtain a visa that would allow the couple to live without problems. However, in Spain, as her states of anxiety increased, Leonora was locked up in a psychiatric clinic in Santander, run by pro-Nazi doctor Luis Morales: in the clinic, the young woman underwent heavy treatment with cardiazol, a drug that, when administered in large doses, causes tremendous convulsions. The experience would scar Leonora quite a bit. However, she managed to get out thanks to the intercession of her father, who, however, wanted to send her to a clinic in South Africa. But when Leonora arrived in Lisbon, where she was supposed to embark, she managed to take refuge in the Mexican embassy: the Mexican diplomat Renato Leduc (1897 - 1976), who worked there, was in fact a friend of hers from her days in Paris, and managed to help her.

In the meantime, Max Ernst repaired to Marseille where he found some painter friends who introduced him to the American collector Peggy Guggenheim (1898 - 1979), who had the idea of getting Max to flee to the United States to get him to safety: the two of them also went to Lisbon and then left for the Americas. And Peggy fell in love with Max. The German painter became her companion, but he did not love her-Peggy knew this, so much so that she would always say that “Leonora was the only woman Max ever loved.” In Lisbon, Max and Leonora met again, but the flame of passion was now extinguished: too distant their goals and too different the paths their existences had taken. Leonora, in fact, in order to escape her oppressive family and in order not to take any more risks in Europe, planned to agree to a marriage of convenience with Leduc in order to obtain Mexican citizenship. Peggy Guggenheim would relate that Max did not want her to marry, because he wanted him and Leonora to get back together, but the girl had already decided to start a new life.

The two new couples thus embarked, in 1941, for New York, where Max and Leonora continued dating for some time, remaining friends. But Leonora, a few months after arriving in the United States, in the summer of 1942 to be exact, separated from Leduc, ending her marriage, and moved to Mexico, where she remained for the rest of her life.Max, who at the same time was married to Peggy Guggenheim (he would later divorce her in 1943, for another of his very short marriages), never saw her again. What remains, however, is what is probably the highest testimony to his love for Leonora: the painting Leonora in the Morning Light, made shortly after Max first managed to get out of the prison camp, during the last days of peace in Saint-Martin d’Ardèche. In a lush, dreamlike-looking jungle, with these very strange winding plants that envelope everything, the beloved Leonora appears, with her thick black hair, making her way through the vegetation, wearing a dress that seems made of the same foliage as the forest. It is an almost mythological apparition, seeming to witness the epiphany of a woodland nymph, a mother nature, or an earth goddess. A creature, in short, more divine than human. Thus, probably, Max was to see the only woman he had ever loved: his Leonora.

|

| Max Ernst, Leonora in the Morning Light (1940; private collection) |

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.