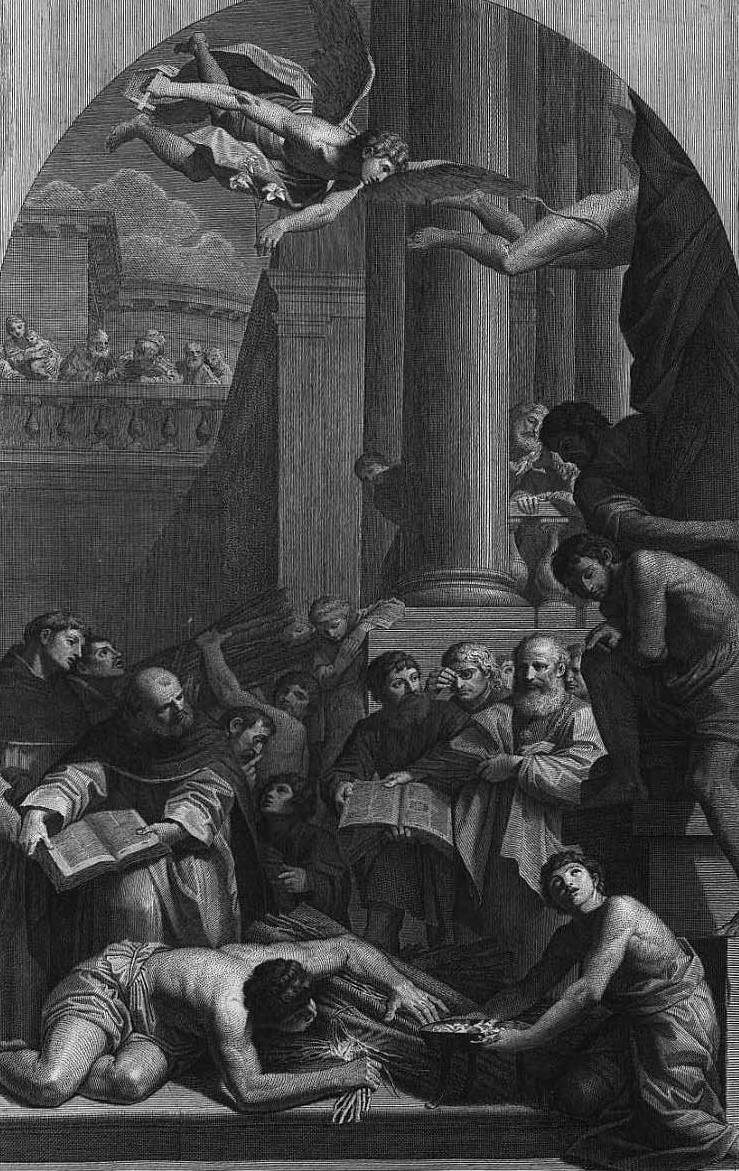

In Western religious painting, the theme of evil has also experienced a constant stylistic and iconographic evolution. It is not the purpose of this paper to reconstruct its evolution and fortune (a work already exhaustively accomplished in Luther Link’s The Devil inArt1), as much as to highlight a limiting case that carries with it interesting implications about the possibilities and limits of the representation of evil within a religious context. The painting that will be examined is Lionello Spada’s Miracle of the Book, 1613-15, in the church of San Domenico in Bologna [fig. 1].

The painted scene shows the moment just before the miracle of the trial by fire. This event is reported to us by Giordano of Saxony, a fervent Dominican. In this miracle, which sees a dispute between the Catholic and Albigensian faiths, the holy books of each creed are thrown by their followers into the flames. The book that will contain the truth of the faith (in the dispute between Catholic or Albigensian faith), will not be burned in the flames2. Thus on one side we will have St. Dominic with his retinue, while on the other side we will have the Spanish Albigensians. There are not many versions painted on this theme, and Lionello’s large canvas immediately stands out for one particularity, namely, having painted the moment just before the trial by fire. That is, the canvas is a depiction of the waiting for the moment of the truth-test (confirmed by the fact that, in the foreground, a man with Michelangelo’s anatomy is still intent on fanning the focherello).

Other antecedent works of this theme are Beato Angelico’s predella in the Louvre [Fig. 2], Pedro Berruguete’s similar setting now in the Prado, or Beccafumi’s work of the same name. The major difference with Lionello’s work is that in these examples the trial by fire is already accomplished and, more importantly, the dispute takes place on an earthly, “human” level, without the involvement of other heavenly spheres such as those of the angels. Lionello Spada’s work under consideration here, in fact, unfolds on two parallel axes that narrate, in the earthly as well as in the otherworldly sphere, in the human as well as in the divine/supernatural world, the contrast and struggle between good and evil, between true faith and falsehood. In addition to the human story we see, in the upper register, an angel with a cross in his hand chasing after another. That the one fleeing is the devil, or at any rate a fallen angel, is ascertained for us solely by the detail, namely the dragon (or bat?) wing glimpsed to the left of the column.

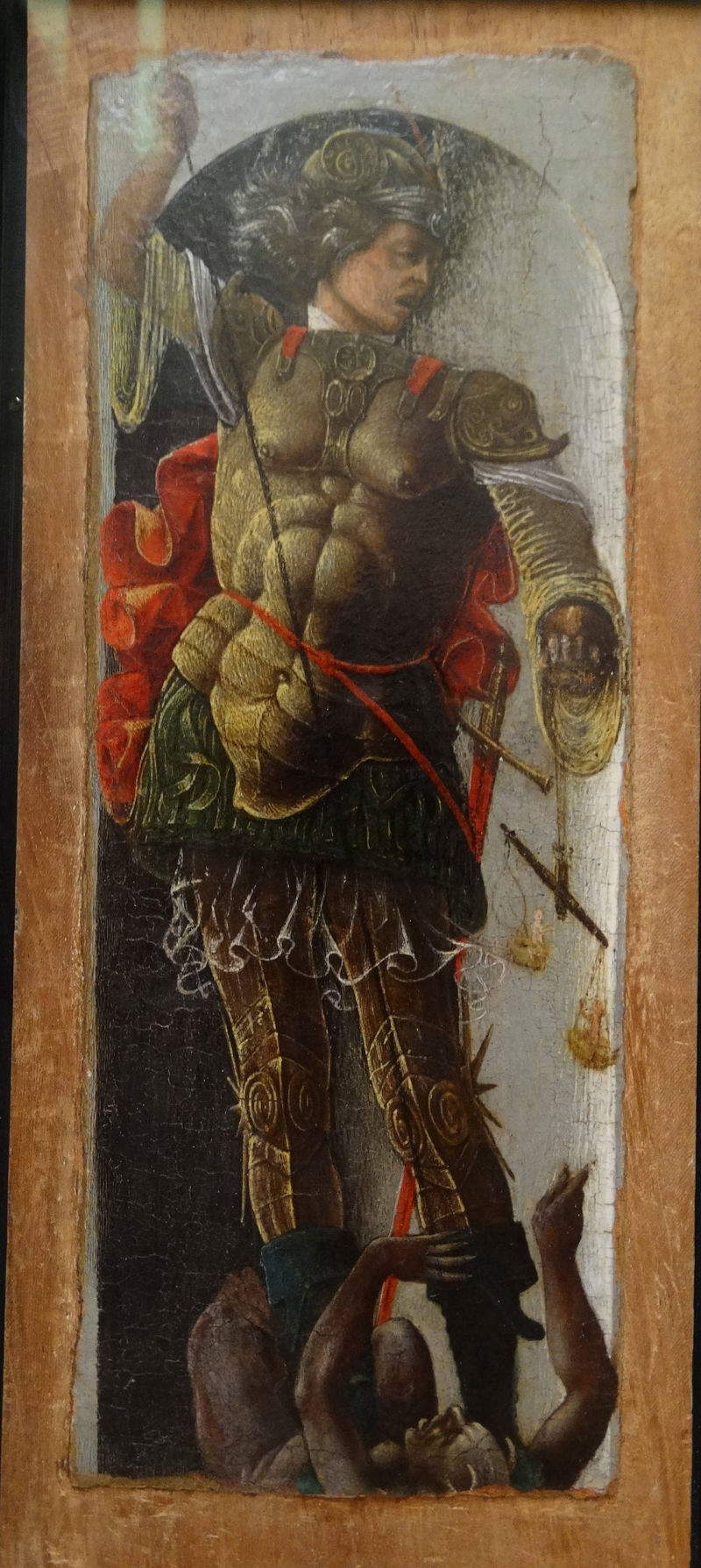

That the devil has this type of wings (different from the feathered of angels) and an anthropomorphic form is an iconographic tradition that was already present and was consolidated with Raphael, in the St. Michael defeating Satan of 15183 [Fig.3]. It is quite possible that Lionello, who had visited Rome in 1607, could have seen this work. Certainly, Raphael’s example was instrumental in consolidating the iconography of the devil, depicting him as human and with dragon or bat wings, without, however, a certain confusion or indeterminacy remaining in the representation of the evil one (still oscillating between dragon, monster, or anthropomorphic form). While the representation itself of the evil one thus oscillates between dragon and anthropomorphic body, the power relations governing the coexistence of good and evil in the same representation are less subject to variation. As a general rule, and all the more so when the demon or evil possesses an anthropomorphic form, the composition always follows a vertical axis, based on values such as superior and inferior, dominance and subjugation, victory and defeat (see the examples of Raphael’s St. Michael, that of Ercole de’ Roberti [fig. 4] or Luca Signorelli [fig. 5], or more generally representations of this theme). We shall see that this clear assignment of roles is lacking in Lionello’s work, while in Lotto’s St. Michael [fig. 6] we already see some variation from the usual representation.

In this work, it is no longer a vertical axis that regulates the relationship between the two opposing forces, but rather two oblique lines parallel to each other. Not only that, Lotto pushes the implications even further by painting the fallen angel as a mirror-like, similar figure whose face is distinctly similar to that of St. Michael. The axis of vertical dominance is attenuated into a diagonal, and the clearly and unequivocally antithetical relationships of the canvas (darkness and light, earth and sky, high and low, rising and falling4) are in this case exacerbated by a clear resemblance of the faces, as if to suggest a relationship of complementarity5. If in Lotto we already have an initial interpretation that departs, in part, from the earlier iconographic tradition, Lionello’s work in turn interprets the clash of opposing forces according to a narrative that poses several problems, both figurative and moral.

Let us return to the Bolognese painter’s canvas [fig. 1 or fig. 7]. We have said that we are in a moment of waiting. Both sides will throw books into the fire as soon as the large figure in the foreground finishes fanning it. The scene is not a triumph, so much as a waiting for triumph, a moment, that is, that precedes the miraculous manifestation of truth. In this waiting on the earthly level, it does, we might say, almost echo the chasing of the angels. Their relationship, in fact, is presented and deployed on a practically horizontal axis, which is quite extraordinary, as seen, for the more or less canonized iconographic tradition. The relationship of dominance on the vertical line, that is, the custom of the triumph of good, is, in this expectation preceding the miracle, eluded, lost. The angels, like the men beneath them, in waiting for the revelation of the true, coexist in a relationship of precarious equality. The angel has not yet cast out the devil, who has not yet fallen, so much as still intent on soaring, as the flame is not yet powerful enough to reveal that which does not burn. The extraordinariness, then, of Lionello’s painting, in this antecedence, is to represent the complementarity and co-presence of good and evil while at the same time avoiding grounding it in a normally canonically stark register of dominance, triumph, and subjugation (i.e., circumventing the symbolic power of the vertical axis by virtue of horizontality).

Such a choice, as far as the narrative moment is concerned, easily leads to scandalous outcomes. To the remedy of a not so clear-cut victory of good, the painter may have represented its triumph through another route, which is that of representation and nonrepresentation. If the coexistence, precarious, momentary, of good and evil is impossible, the only way to avoid it will be the forclusion of evil. Indeed, only a small part of a wing (of a dragon, of a bat) allows us to recognize that we are dealing here with Satan, or one of his followers. Then again, such a relationship between good and evil, between believers and heretics, can appear scandalous, especially if the painting is placed in a church. The only way to deal with evil, in this case, and starting with the choice of this narrative moment (prior to the miracle), seems to be only to erase it, to hide it. Lionello’s process is reminiscent of the psychic process of removal. Something unacceptable to the “psychic” balance of the painting is erased, removed, censored. Erasure, removal, censorship, which also affects, through black drapery, the column, whose relief and plasticity are practically reduced to zero6. From this point of view, the column is the target of an absolutely dark chromaticism, such that it becomes, in short, a stain: the drapery that falls on the column is not treated here as it is normally used in painting, that is, as exaltation and testimony of the modeling, with all the possibilities of plastic representation that such an element allows. Rather, in this case, the black drapery is what allows the zeroing out of all modeling. This negative flattening of form stands out even more when comparing Lionello’s work with its engraved reproduction by Traballesi, where in the latter one can discern a certain “invention” of folds that is not at all consistent with Leonello’s work.

In this sense, the reasoning goes as far as the paradox of a presentification of negation through negation itself: the body of Lucifer (or his servant) and what occludes him (the column) appear in the canvas as areas where painting has ceased to represent, where the brush has ceased to define. In this sense, the painting here offers two stasis to that vocation of painting that descended from the Renaissance: the resetting to zero of what offers the best solution of modeling (the drapery), and the occlusion of a character who in this way does not adhere to the vocation of the istoria (a poetic, Albertian one, still well present in Leonello’s historical moment), that is, of representing the event through the legibility of the face, of movement, of the body7. If in Albertian instoria the movement of the soul becomes knowable by the movement of the body, here emerges the essential enigmatic nature of this concealment: the fallen angel becomes an absence present in the painting, a syntagma of illegibility within the figuration.

Leonello’s canvas thus ushers us into a game of presence and absence, delivers to the canvas a remainder, a zone of shadow brought into the light, a fold with respect to the generosity with which representation usually offers itself to visibility. Rather, it is here the concealed that becomes visible. This ambivalence between representation and nonrepresentation (“making oneself glimpsed, that is, hiding in order to be sought ”8), actualizes in this work a simultaneity that undermines a purely symbolic legibility of the painting, bringing out an eccentric moment that leads it back to a moment of pure visibility: present to the view and yet, like the disappearance of the fallen angel and the column, absent to language.

1L. Link, The Devil in Art, Bruno Mondadori, 2001, especially pp. 191-226

2Jordanof Saxony, Origins of the Order of Preachers, Ch. XV: “finding St. Dominic at Fanjraux in Languedoc, disputing with the heretical Albigensians and failing to convince them of their error, he resorted, in agreement with his adversaries, to the trial by fire by throwing into the flames the books containing the professed doctrine of the two sides; the saint’s books were spared.” .

3“After Raphael, the theme of Michael against Lucifer in human form appears, with minimal variations, in an unknown number of paintings,” in L. Link, The Devil in Art, cit., p. 205

4“Michael on high, in flight, clothed, armed and Lucifer naked and upside down, unarmed: nudity and upside down position serve to qualify as opposites the two angels, otherwise identical,” in San Michele caccia Lucifero, F. Coltrinari in Lotto nelle Marche, Silvana Editoriale, Rome, Scuderie del Quirinale, 2011, p. 241

5“Usually, Michael was depicted standing over fallen Lucifer. Or Lucifer is falling into hell. But Michael is always standing: the message lies precisely in the contrast between the two positions. The stability of Michael’s posture indicates the stability of his power. Lotto changed this arrangement by drawing the longitudinal axes of Lucifer and Michael diagonally and parallel to each other. This structural parallelism reflects the artist’s mystical interpretation. Michael and Lucifer are identical; they have the same body and face. It is as if we see the two gametes of a single zygote. Michael and the other face of Lucifer,” in L. Link, The Devil in Art, cit., p. 201

6Thecolumn “dressed” by a tarpaulin was already depicted by Lionello in the Martyrdom of St. Cecilia in San Michele in Bosco. Several scholars have pointed out a solidarity of figurative solutions among the group led by Ludovico Carracci. The same element would be repainted on a few occasions by Pietro Faccini and literally by Francesco Brizio in the Idolatry of Solomon. It is possible that the identical repainting of the motif is done by Brizio around 1517, that is, while he was intent on painting the Judgment of Solomon for the Florentine Galleries (Chronology of the “Judgment of Solomon” stated in The School of the Carracci. Dall’accademia alla bottega di Ludovico, edited by E. Negro and M. Pirondini, Artioli editore di Modena, 1994, p. 69). In this element, beyond artistic paternity, one can nevertheless discern that degree of mixing of styles that took place in the workshop of San Michele il Bosco (cf. M. S. Campanini, Il chiostro dei Carracci a S. Michele in Bosco. Rapporti, Nuova alfa Editore, 1994, pp. 4-6). As for a possible symbolic meaning, nothing has been found in iconology nor, at this time, in the discipline of architecture. The motif could simply be a “variety” of Mannerism or nascent Baroque.

7L.B. Alberti, De Pictura: I,2: “I sign here appeal whatever stands to the surface so that the eye may see it”; II, 41 Then will the istoria move the soul when the men therein painted much will pose its own movement of mind. It intervenes from nature, which nothing more than she finds herself rapacious of things similar to herself, that we weep with those who weep, and laugh with those who laugh, and grieve with those who grieve. But these movements of the soul are known by the movements of the body.“ II, 42: ”So therefore it behoves painters to be most familiar with all the movements of the body, which well they will learn from nature, well that it is a difficult thing to imitate the many movements of the soul.“ II 44: ”so to each one with dignity let his movements of the body be to express what you want movement of the soul; and of the very great perturbations of the soul, likewise let very great movements of the limbs be. And let this reason of common movements be observed in all animants."

8E. Castelli, The Demonic in Art, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin, 2007 (first edition 1952), p. 21

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.