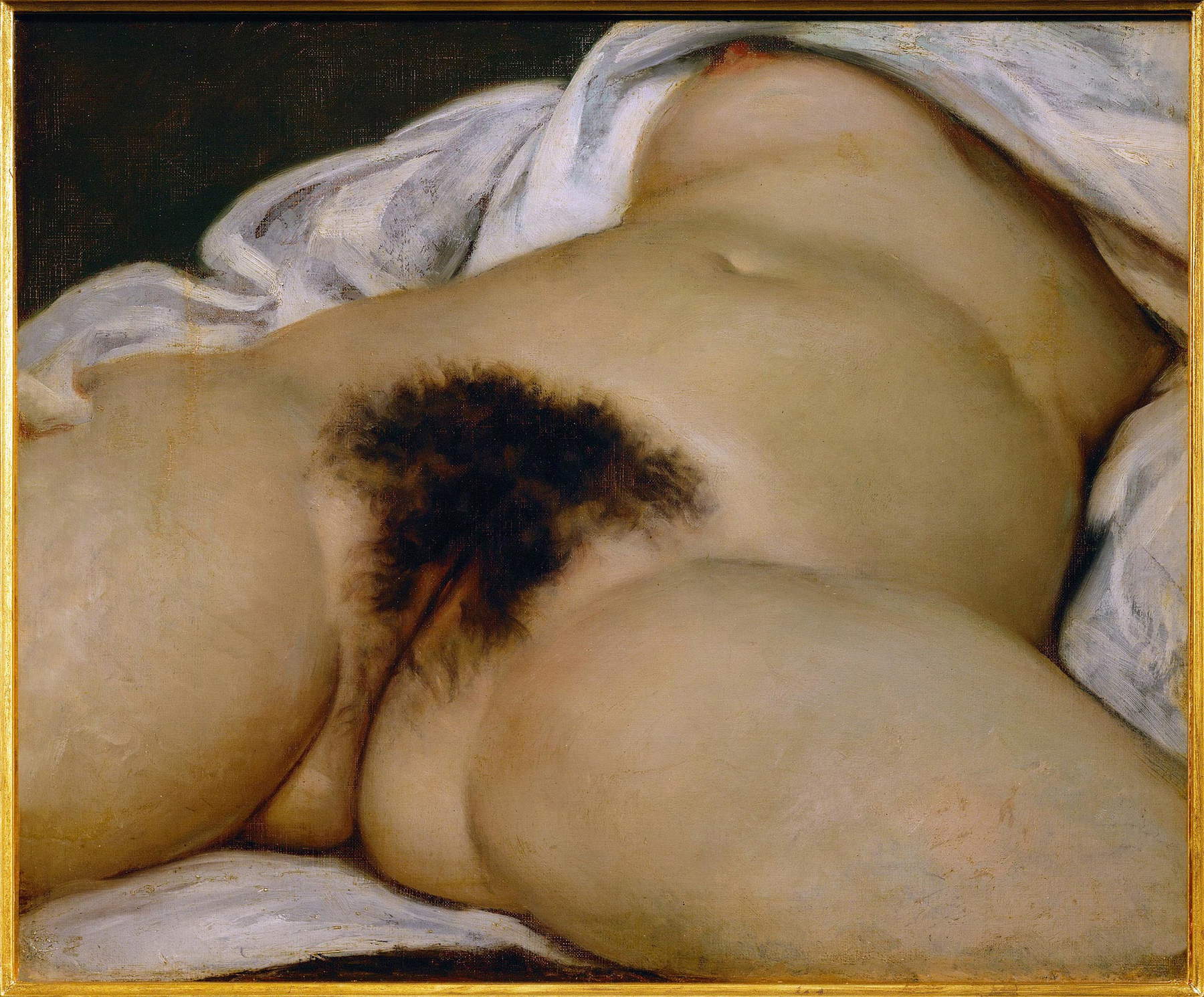

Among the works representing female bodies, bearers of more or less erotic messages, L’Origine du Monde by Gustave Courbet (Ornans, 1819 - La-Tour-de-Peilz, 1877) is the one that more than any other engages with fierce realism: it is a work that helps us understand how, throughout history, aesthetic canons and the values conveyed by the body have undergone abrupt shifts and reversals, culminating in a society that for centuries chose to relegate the explicit representation of sexuality in art to the mere realm of pornography.

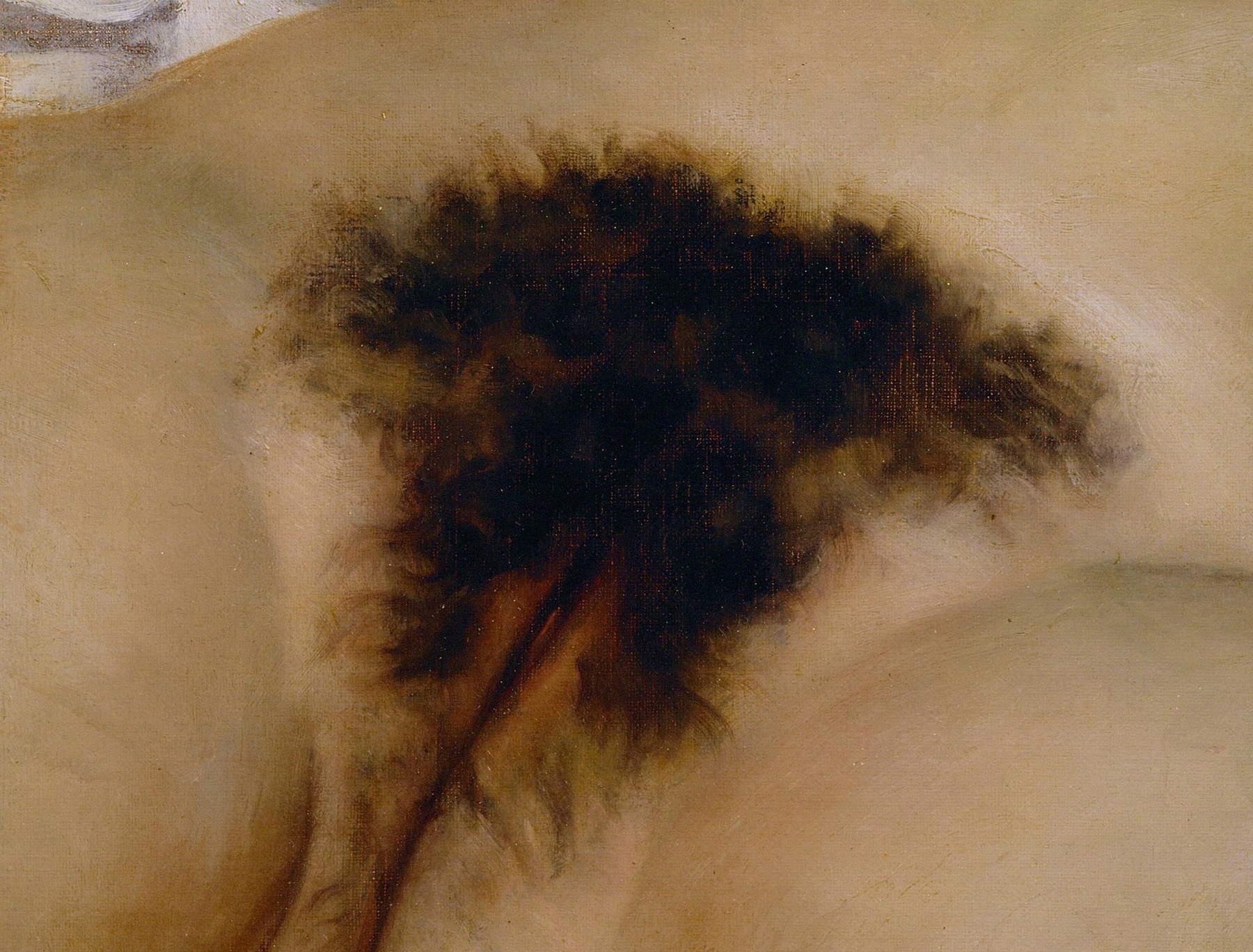

BeforeOrigine du Monde, no one had ever placed the relative so dangerously close to the female sex. The point of observation is placed between the woman’s thighs where her right leg follows a diagonal along with her prone body, whose realistic fleshiness slowly leads the gaze to the exposed genital area without any veil or inhibition, while the rest of the figure recedes, eluding curiosity. Courbet does not merely hint, as Francisco de Goya did a few years earlier with the scandalous Maja desnuda or Édouard Manet with the controversial Olympia, at a shy hairiness. Here the hirsutism of the woman is key to the extremely brazen eroticism of the canvas.

The painter from Ornans was by this time accustomed to being fingered as a scandalous artist, for his realism began to destroy the academic tradition already by bringing into the foreground the faces and postures, often hunched and far removed from the manners of the powerful, the common people and the poor. Indeed, it might seem almost endless the artist’s transgressive works, and among them it would be impossible not to mention Un enterrement à Ornans of 1849, which is shocking for its rude depiction of the burial of a stranger surrounded by now weeping, now indifferent figures, but also the canvas representing a group of drunken clergymen walking aimlessly, Le retour de la conférence of 1863, which was bought by a fervent Catholic only to be destroyed. The following year, in 1864, was the turn of Vénus et Psyché, a work rejected by the Salon for indecency. And again, almost as a joke, in 1870 the artist refused the appointment as a knight of the Legion of Honor, and in his June 23 open letter addressed to the Minister of Fine Arts Maurice Richard, Courbet wrote: “Honor is neither in a title nor in a ribbon; it is in deeds and in the motive of deeds. Respect for oneself and one’s ideas is the fundamental part of it. I am fifty years old and have always lived free; let me close my existence free; when I am dead it must be said of me: here is one who has belonged to no school, no church, no institution, no academy.” He refused the honors, but by many he was described as a bumptious and excessively full of himself as, for example, by Ludovic Halévy, who in his Trois dîner avec Gambetta reports that on May 28, 1882, during a dinner Léon Gambetta, in front of theOrigine du monde Courbet exclaimed, “You find it beautiful and you are right. Yes, it is beautiful indeed beautiful. And think, Titian, Veronese, their Raphael, myself, we have never done anything more beautiful.”

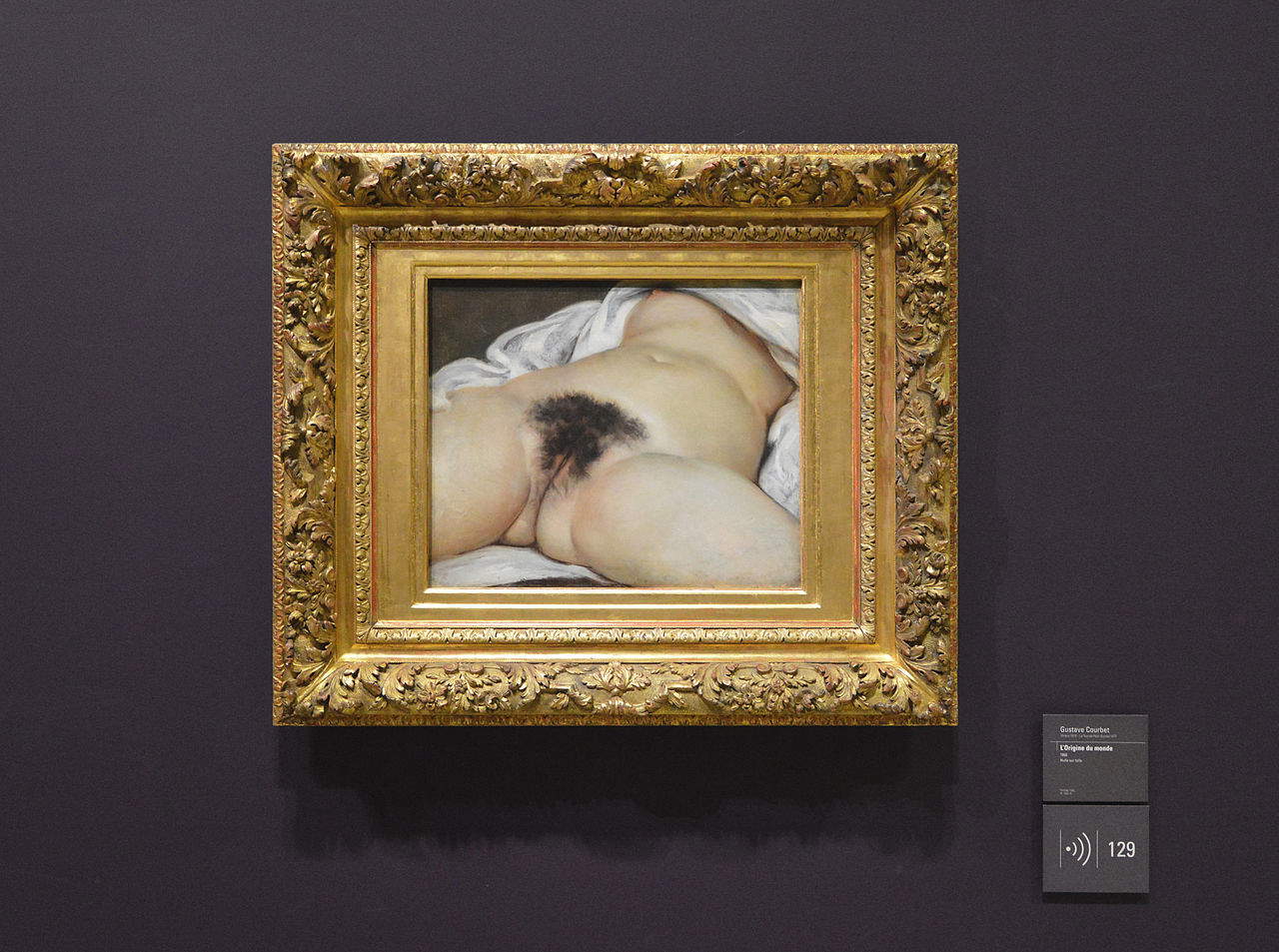

L’Origine du Monde was commissioned from him, in 1866, by the Turkish-Egyptian diplomat Khalil Bey, who owned a large collection of erotic works, including Ingres’ Turkish Bath and Courbet’s Sleepers, also by Courbet. Very little information, however, comes to us about the painting’s subsequent owners, but we do know that before making its tentative entry into the Musée d’Orsay collections in 1995, the painting was counted in the collection of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

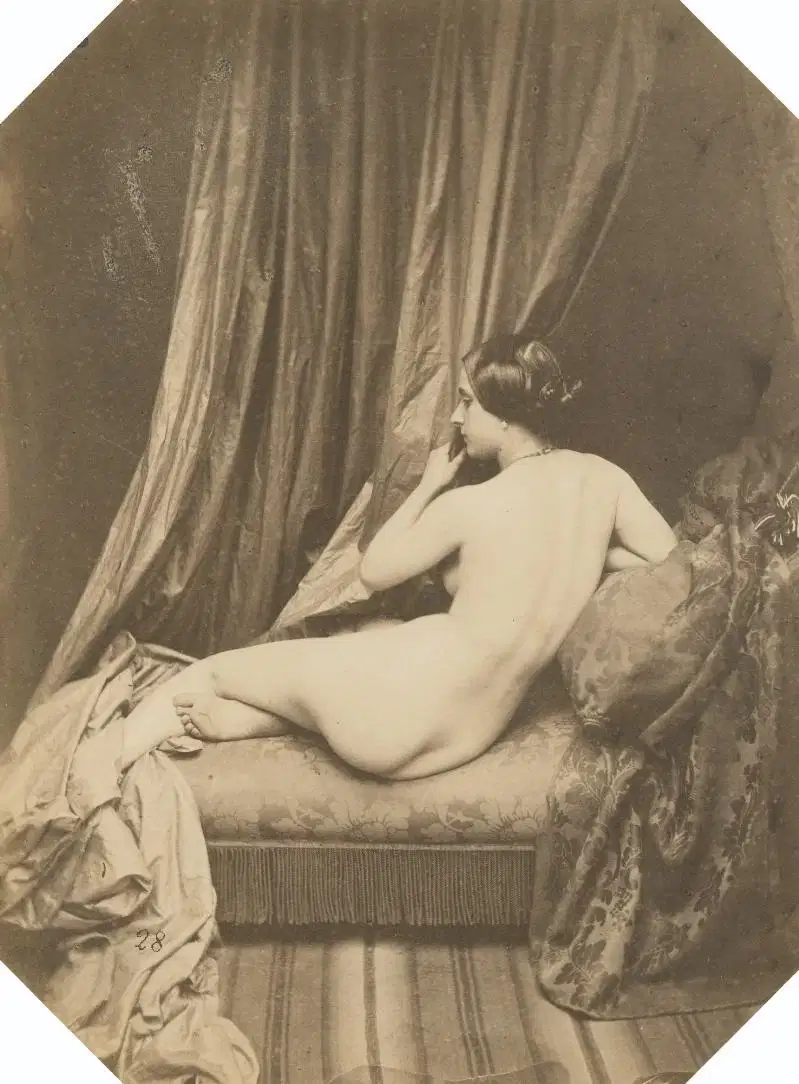

InOrigine du monde, the artist completely abandons his brush to a never-before-seen boldness that gives the work a strange, but extremely fascinating, seductive power. In the center of a canvas measuring approximately 40 by 50 centimeters, Courbet depicts the female genital organ, creating not only a scandalous work, but also enormously revolutionary in composition and realism, so much so that it is considered a symbol of political unrest and obscenity, representing the most extreme point of realist achievement. Courbet, through a few brushstrokes that effectively position the orientation of the folds and the overlapping of the fabric, whose rapid and vibrant treatment contrasts with the delicacy of the complexion, abducts the viewer’s gaze by forcing it violently. We also know, and now with absolute certainty, that for his works he did not only use the more classical copy from life, but preferred to help himself with images sold under the table by famous photographers such as Auguste Belloc.

There were many photographs depicting only organs of female genitalia, and it is not difficult to imagine what the inspiration might have been for his origin of the world, but unfortunately this was a practice viewed almost as a social scourge, so much so that in 1855 the Paris Police Prefecture searched Auguste Belloc’s studio and found about 4,000 shots and compiled a report on the production of pornographic photographs.

The hypothesis of the artist’s use of photographs was formulated by the general curator of the Musée du Louvre, Dominique de Font-Réaulx, and is confirmed by the studies carried out on the very firm drawing and the almost total absence of repentance on the painting. In spite of this research, however, it would not be true to say that as soon as we find ourselves before the small but unwieldy canvas, the almost morbid need to discover the entity of the model so that we can give her back a face, perhaps in a mere attempt to humanize her or simply associate her with someone distant from us, does not make room in our minds.

Initially, experts on Courbet’s work speculated that the belly belonged to one of the patron Khalil Bey’s mistresses precisely because of his reputation as a great seducer, while historian Gérard Desanges, in 2011, advanced the idea that it might be a woman known for her literary salon in Paris, a certain Jeanne de Tourbey. Today, however, the vast majority of historians, including Courbet expert Jean-Jacques Fernier, agree on the identity of Joanna “Jo” Hiffernan, wife of painter James Whistler and later of Courbet. The Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France team had the opportunity to study Courbet’s scandalous painting twice, and beginning in February 2007, its researchers carried out a comprehensive examination of the work that uncovered secrets and also debunked various assumptions.

Initially it was thought that L’Origine du monde was nothing more than a canvas fragment of a larger composition. This idea was presented to the public on Feb. 7, 2013, by the weekly Paris-Match, which devoted a very long article to the subject entitled “Le secret de la femme caché” (“The secret of the hidden woman”), where it recounted how an art enthusiast found, from a junk dealer, a woman’s head painted on a canvas bearing the stamp of a merchant of the time, where in the laboratory they proved that it was a fragment of a composition whose elements strongly matched the origin of the world. According to this theory, Courbet painted a large female nude that was later cut into two pieces by the same artist, resulting in two separate works. Examinations in 2013, however, showed that the painting always retained its original format and was never cut.

An iconoclastic and brilliant painter, Courbet was accustomed to and strongly loved to provoke, disrupt and above all destabilize, which is why he very often changed the format of his compositions as he worked, amusing himself by reducing or even enlarging them. A significant example of this is theSelf-Portrait at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Besançon, which comes from a larger composition, while it would seem that the genesis and particularity of L’Origine du Monde would have nothing to do with the simple, and almost predictable, mutilation of a large-format painting. It would have been all too simple, and fortunately Courbet turns out to be a subtle and daring painter who manages to sublimate the most difficult themes by elevating nothing more than the depiction of sex to the subject of the painting, creating a masterpiece where many other artists would have created nothing but banality.

The studies cited earlier have shown how the composition was conceived in exactly the format we see today without ever having been cut later, but simply the artist obtained from a merchant a canvas already stretched on a frame, prepared and applied while the canvas was still on the roll. This was the reason why it overflowed slightly and that is why it was thought to have been cut.

A photograph of Auguste Belloc

A photograph of Auguste Belloc

Gustave

GustaveThe X-ray also showed how the subject matter was very light and impalpable, discovering that the painter worked gently and unhurriedly in small areas, avoiding flat drafts and patiently punctuating the surface with small luminous touches that aimed to suggest all those subtle imperfections of the skin giving, thus, body, thickness and life to the flesh, making it so real that one could almost feel it by touch. Another infrared photograph in false colors then highlighted some minor mishaps, such as a vertical line located above the right thigh that takes on a pink hue and indicates an old tear, while another tear is located below the left breast. The work, unlike almost all of Courbet’s others, is not signed, but its attribution is undoubtedly to be given to the Frenchman precisely because the technique used could only have been his and especially because the work was mentioned several times by biographers of the time and appeared, moreover, covered by a vine leaf, on one of the caricatures of the painter.

It is impossible for us to know for sure the reason for the anonymity in the canvas that Courbet himself described as more beautiful than the works of Titian and Raphael, but what we do know is that the artist would never stop revisiting and studying the female nude, which under his very precise brushstrokes never turns out to be pornographic or lecherous, but simply a vehicle for a raw and bold realism. L’Origine du Monde is an almost anatomical description of a female genital organ that is anything but sweetened, screaming at the top of its lungs to be looked at without malice or voyeurism as, despite its bluntness, it draws violently from tradition looking to Titian, Veronese, Correggio, and carnal and lyrical painting.

This shocking work has seen shame and embarrassment in the eyes of observers, has known censorship, even recent censorship, but most of all unimaginable fame. Everyone knew it, although very few had the privilege of seeing it in the artist’s time. Courbet, with this highly restrained canvas, reminds the viewer that there is nothing more subversive and rebellious than pure reality, creating a dangerous short circuit between present and past.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.