The dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, struck on August 6 and 9, 1945 in the first and only nuclear strikes in history, brought unprecedented devastation to the two cities, marking one of the darkest and most decisive pages in modern history. To fully understand the causes and consequences of the tragedy, we must first trace the historical context that generated it. In 1940, Japan launched a military campaign in southern Indochina, then under French control, with the intention of consolidating a network of Asian nations freed from European influence and united under its leadership. The Japanese occupation initiative of Southeast Asia was idealized under the expression Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The occupation of Indochina triggered an immediate reaction from the United States and European powers, concerned about their own interests in the region. Harsh economic sanctions followed (including an oil embargo that cut direct supplies to Tokyo by 90 percent), putting Japan in an increasingly critical position.

Pressure from trade blocs contributed to the Japanese government’s decision to strike the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, an attack that came on December 7, 1941. Indeed, the goal was to cripple the U.S. Pacific Fleet so as to prevent its intervention in Japanese expansion plans toward Anglo-French-Dutch colonial territories in Southeast Asia. At this point, the attack marked a turning point: on December 8, after years of neutrality, the United States officially entered the war against Japan. Over the next four years, U.S. forces faced a long and wearisome conflict against the Japanese Empire, fighting between China and the Pacific archipelago.

Despite a balanced first phase, the fall of Nazi Germany changed the balance. Decisive, however, was the secret development of the nuclear weapon under the Manhattan Project, led by the United States with the cooperation of the United Kingdom and Canada. Scientific minds such as Robert Oppenheimer, Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi worked on the development of the atomic bomb, culminating in the Trinity test in the New Mexico desert.

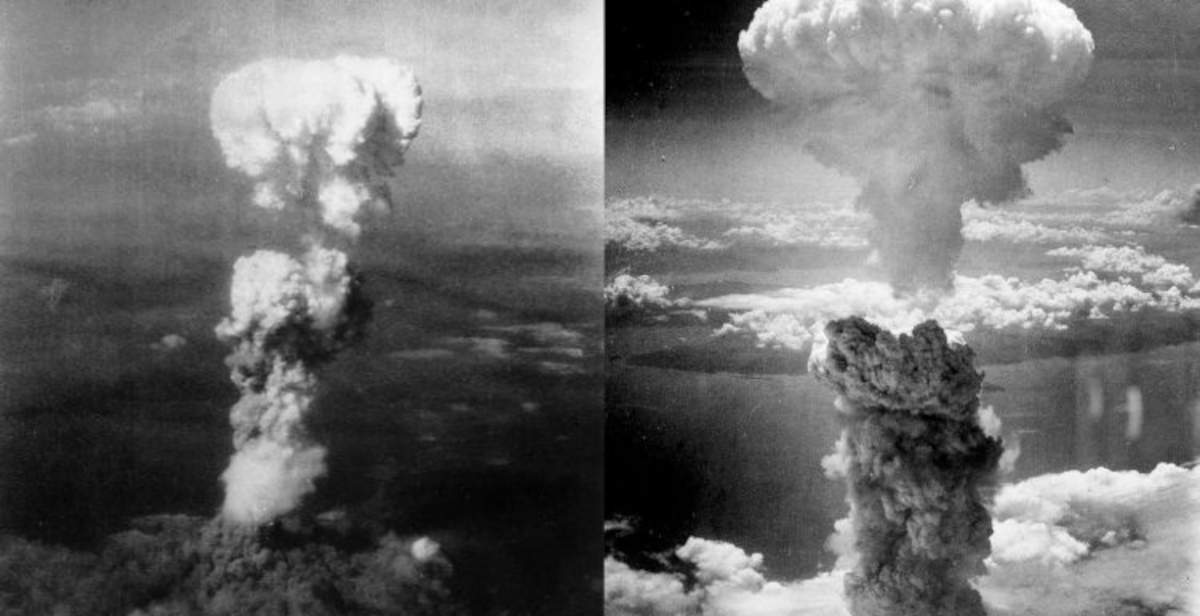

Thus, three weeks after the first test, at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, a U.S. bomber dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in a conflict on the city of Hiroshima. The explosion caused by the bomb, called Little Boy, caused instant devastation: the city was leveled and some 80,000 people died instantly. Three days later, on August 9, a second nuclear device, called Fat Man, struck Nagasaki. The two missions together caused an estimated 150,000 to 220,000 direct casualties, and Japan’s surrender (although it did not become official until September 2 of that year) was announced six days after the second bomb was dropped, on August 15.

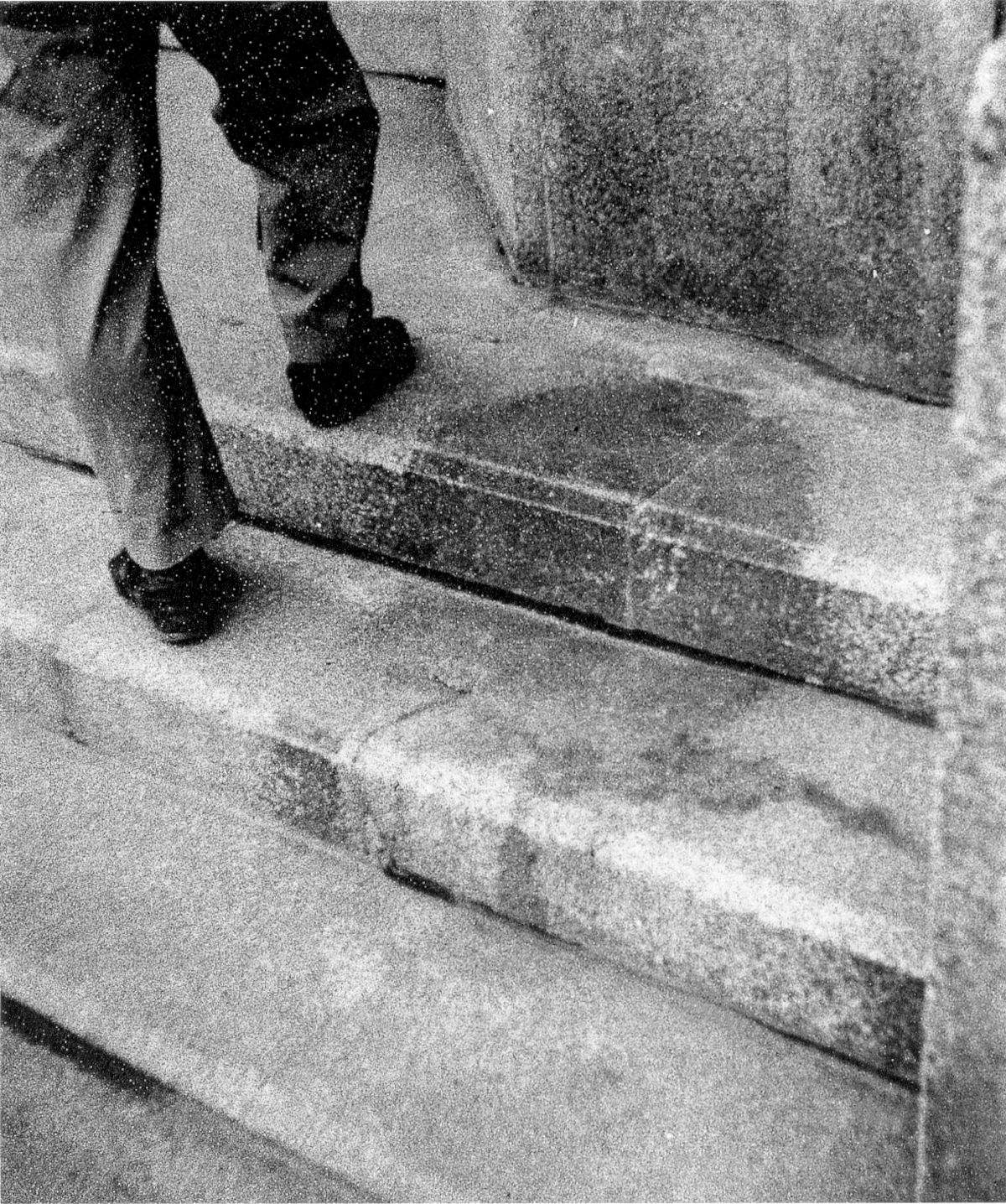

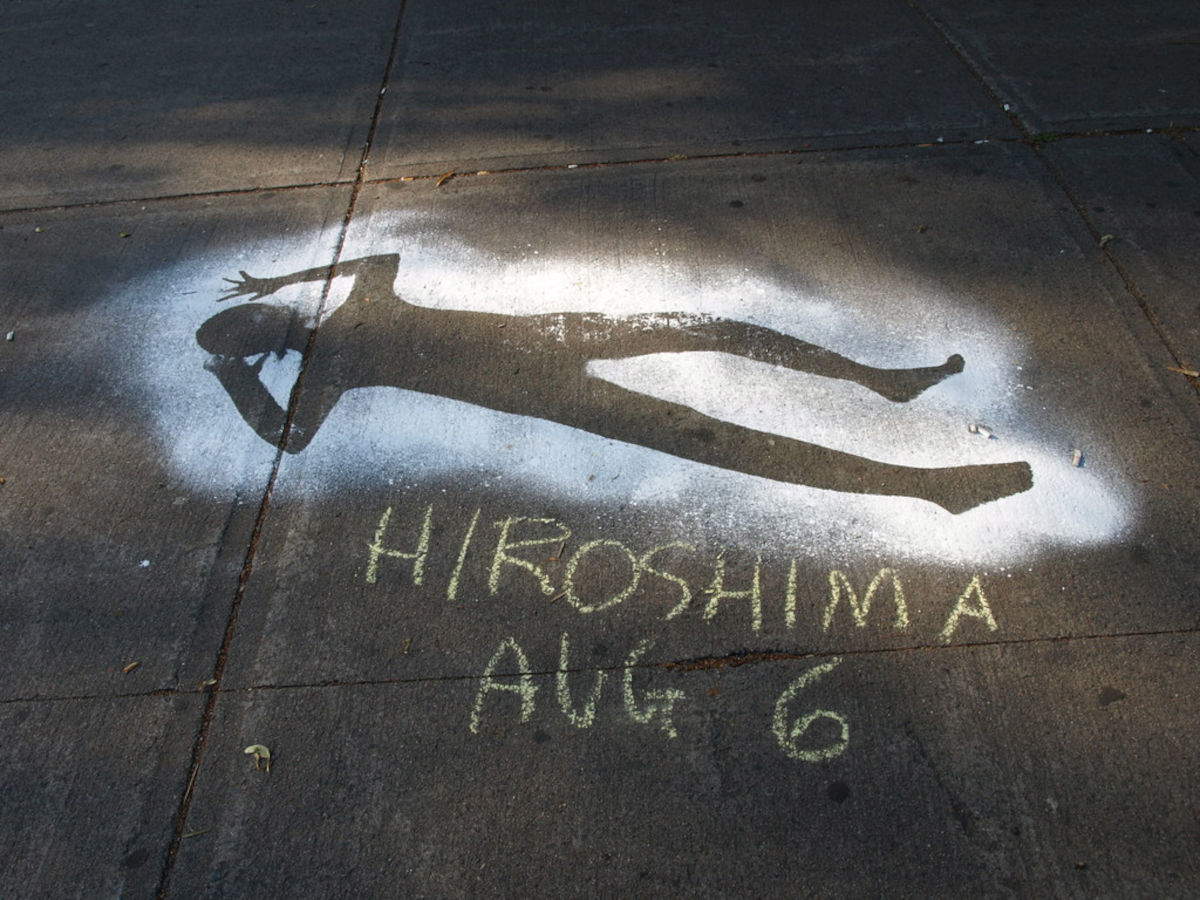

Among the accounts of the catastrophe are details that are still striking in their symbolic force today. In front of the entrance to the Sumitomo Bank branch in Hiroshima, stone steps preserve the human trace left by a body exposed to the extreme heat of the detonation. The surrounding surface, completely bleached by the heat intensity, makes the shadow stand out as the imprint of inescapable death. The figure is believed to have belonged to a person waiting for the bank to open, caught in the explosion a few meters from the epicenter. Over the years, several families have hoped to recognize in that silhouette a missing loved one. Inside the Hiroshima Peace Museum, the trace has thus become a powerful universal symbol. In fact, the shadow imprinted at the entrance to the bank is not the only one. Several other, equally dramatic traces have been found on stairways, walls and urban surfaces in the city, where human bodies were instantly vaporized by the power of the nuclear blast.

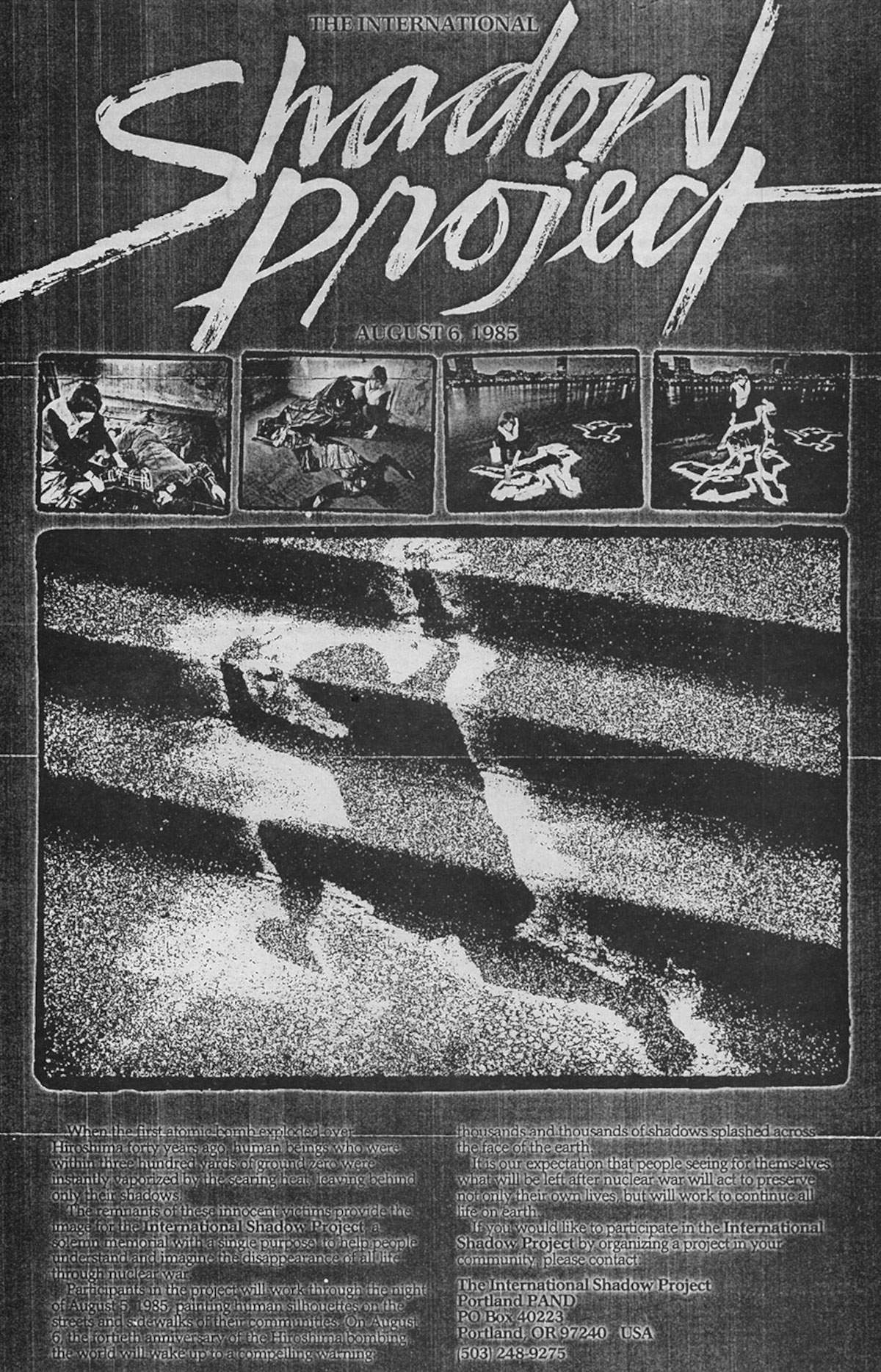

Out of that awareness was born, theInternational Shadow Project, perhaps the largest anti-nuclear art initiative ever. Sponsored by the Performers and Artists for Nuclear Disarmament (PAND), with co-directors Alan Gussow and Donna Grund Slepack and coordinator Andy Robinson, the project was inspired by the shadows fixed on the walls and ground by vaporized human beings in Hiroshima, some 33 meters from the point of impact.

In the first moments after the blinding flash caused by the bomb on Hiroshima, people within three hundred meters of the hypocenter were literally vaporized, leaving only their shadow outlines imprinted on the steps. The remains of the victims provided the central image and theme for Shadow Project, a solemn memorial with one goal: to help understand the loss of life in the abyss of a nuclear war through a widespread, participatory work of art. In the hours before dawn on August 6, 1982, certain areas of Manhattan were symbolically designated as the virtual hypocenter of a nuclear explosion. In those locations, artists and activists traced life-size silhouettes on streets and sidewalks. They were anonymous, human figures, portrayed in everyday acts: people walking, sitting, loving, playing, working, talking. Scenes of ordinary existence suddenly frozen in ghostly images scattered across the still-living city.

“Dear friends,” wrote two members of the group Performers and Artists for Nuclear Disarmament (PAND) in an announcement that began circulating on the Mail Art Network circuit in 1985, “August 6, 1985 will mark the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. [...] As a way to commemorate the first nuclear holocaust, we are organizing a worldwide event, the INTERNATIONAL SHADOW PROJECT, which will help people to see the consequences of the nuclear catastrophe and affirm its human dimensions. When the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima in 1945, human beings who were 33 meters from the zero point were immediately vaporized by the heat of the blast, leaving behind only their ’shadow’. [...] Before dawn on Hiroshima Day, August 6, 1985, we will paint silhouettes of human beings engaged in various activities. These nonpermanent shadows will be found on public streets and sidewalks in various communities around the world. The silent witness of these anonymous human silhouettes will dramatize what would be left after the nuclear war.”

Those who woke up that morning were confronted with an altered urban landscape populated by absent presences. Indeed, the silhouettes appeared as evidence of a life that could have been erased without witnesses. What, then, was the intent of the project? To point the living to a concrete vision of atomic destruction, impossible to observe in real time: a scene that no one could ever see, if it really happened. The project therefore represented an ethical and imaginative challenge: to make annihilation visible, inviting everyone to confront the real possibility of human extinction. Thus, by painting shadows on the streets of the world, art became an act of memory and hope. The hope was that, in front of those images, people could awaken the common consciousness, understand the magnitude of the threat and act to protect life.

On the 40th anniversary of the bombing, August 6, 1985, the project then expanded to numerous cities. In Italy, the initiative saw the participation of important artists such as Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Ruggero Maggi, Giacinto Formentini, Katia Camozzi, and Enrico Baj, whose installation at Villa di Serio, on the occasion of the Biennale d’Arte, became one of the most important moments of the commemoration. Baj made four large canvases displayed on a tall pylon in the courtyard of the middle school, while at various points in the village, in front of the church, town hall, and schools, silhouettes, shadows, and evanescent figures were drawn and torn, recalling the victims of the atomic bomb. The event, coordinated by Maggi and Formentini, attracted Italian and international artists, along with the Villa di Serio School of Art. After the installation, some participants lay on the ground, physically evoking the annihilation of Hiroshima, while an anomalous sun illuminated and warmed the collective simulation.

At the same time, similar installations were set up in 35 U.S. states, 7 Canadian provinces, and nations such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, and Monaco. The message was global: remember and raise awareness. Not coincidentally, among the Italian promoters was Enrico Baj, founder along with Sergio Dangelo and Gianni Bertini of the Nuclear Movement, born in Milan in 1951 (their first manifesto was published the following year and another in 1959). The group, in open opposition to geometric-abstract art (linked, however, to informal art), in fact proposed an aesthetic linked to theatomic age, using automatic techniques and materials such asheavy water (a term Baj assigned to the enamel paint and distilled water emulsion he used) to evoke the devastated landscapes and threats of the present time. Indeed, in his works, Baj alternated denunciation and sarcasm, as in the series of deformed military officers, most notably Fuoco! Fuoco! of 1963-64. In any case, the Nuclear Movement came to an end in the early 1960s.

In artist John Held Jr. ’s papers devoted to Mail Art between 1947 and 2018, titled Shadow Project: a collaboration between the Mail Art Network and peace activists in the contemplation of an uncertain era, the artist recounts how instead Shadow Project also inspired numerous art exhibitions. Prominent among them was an initiative sponsored by Harry Polkinhom, who invited Ruggero Maggi to participate in an event held at San Diego State University’s Imperial Valley campus. The works already exhibited in Japan during the 1988 edition were presented for the occasion, as well as new works specially conceived for the California event. In the introductory text to the exhibition, Polkinhom observed, "It is important to note that many of the works related to Shadow Project combine visual and verbal elements, as if to overcome the communicative barriers imposed by cultural, linguistic and media differences. Yet despite these complexities, the message that emerges is direct: survival comes through the ability to accommodate and tolerate differences."

Even Karl Young, curator of the 1990 exhibition at the Woodland Pattern Gallery in Milwaukee (in the state of Wisconsin, U.S.), noted how many participating artists expanded the discourse to other urgencies, such as domestic violence, censorship, AIDS and colonialism, without focusing solely on the nuclear threat. In any case, two impressive works by Clemente Padin, a Uruguayan poet and artist, made in Montevideo (Uruguay’s capital city), traced the silhouettes of missing people in his country-a second thematic layer that invited the audience not to confine the discourse on nuclear weapons to too narrow a view.

In a review of the performance that John Held Jr. presented in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1989, critic Karlen Ruby wrote "One wonders whether these performances and related activities will leave a lasting mark. But have not the tens of thousands of victims of Hiroshima in 1945 already left an indelible mark? For those born after that event, the meaning is unequivocal: this must never happen again. Held’s Shadow Project, as simple a gesture as it may seem, raises deep emotions and draws attention to such fundamental issues as humanity’s survival, nuclear disarmament, and peace. An invitation to reflect, now more than ever, in a time shot through with uncertainty."

In what, therefore, is the legacy of the events that led to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki reflected? Certainly in historical trauma, but also in the memory of humanity. A memory that, through time, has tried to remember, understand, process, and only then tried to act. The International Shadow Project’s art and memorial project sought to transform that memory into a universal warning, and made visible the human cost of nuclear war. The goal? To call for moral responsibility toward disarmament and peace. Shadow Project thus wanted to give substance to what nuclear power has violently obliterated.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.