If one steps outside the Chagallian interpretive scheme that interweaves Chassidic Judaism and a certain ethnic-religious idea of fairy-tale reality that finds in the flying sweethearts and in certain upside-down world situations typical of the fairy-tale vision with animals that sometimes seem, as already in the classical context, to personify themselves into beings that perceive nature as sentient reality; lo and behold, stepping outside the vision that recurs perhaps even more in the interpretation of Chagall’s work than in his own idea of art and the world, one would moreover risk discovering that this is a “good,” or rather goodist, vision of Chagall, because it is sentimental, where the link with the archaic Israelite, biblical and tribal tradition as it were, is diluted. To deny this is like wanting to ignore that Chagall’s best-known painting, which we might call a magical realism tinged with romanticism, had been preceded by a panic and lyrical dimension, and nonetheless open to the shattering of the world brought by the avant-gardes, futurism and cubism first and foremost, but also the varied pursuit of abstract languages. From this point of view, the Chagall most faithful to his own Russian soul, the peasant one that he would never forget, is manifested in the 1910s, when his ethnic, or so to speak popular, loyalty is measured by the qualitative leap that drives him in 1907 to leave Vitebsk, the “native village”, bound for St. Petersburg, where on the one hand he will forge relations with the institution of Fine Arts, with the classical form in short, but on the other hand, the meeting with Léon Bakst and then the landing in Paris in 1911 through the discovery of modern and avant-garde art, initiate a consensual transformation of his talent. The crossing of the frontier to Paris also occurred by changing his own name from Moishe Segal or Šagal to Chagall (adapting it to the French pronunciation, a very clear sign of his decision to become a Western painter).

It was the beginning of that expressive maturation from the earthy root that the very young Marc had manifested in drawing even before any schooling: he knew how to grasp to the utmost truth of sign and form the inner nature of reality, an intuition of the essence of things, typical of visionaries, according to Henri Focillon, who argued that these were not men endowed with an imaginative or primitive vision of reality, but capable of seeing things from theinside, in the genetic heritage if you will, moving inside reality itself and bringing to light from the deepest depths, like a diver, what the sea has swallowed and hidden. Chagall belonged to this species of underwater artists capable of seeing and tracing to immense depths that substance of things which procures, when shown to us, dizzying emotions. It was a kind of rootedness to the land, as in the pastoral and peasant world, which preceded the socialist model of the prolet and the kolkhozes. The model of the soviets imposed a new sovereign, the state demanding to put together labor, tools and purposes toward it oriented in a collectivist way, which took the place occupied for centuries by the czars.

Chagall was a wild, primitive, even light-hearted soul, capable of dreaming with that dreamlike force that, even before it generated his painting known today, insufflated in the forms that came out of his eyes and hands this spirit of freedom that belongs to man as the image of the creator; man as farmer and rancher, bound to his field and village, reveals himself as the custodian of creation, certainly, but he is even first himself a fruit of that likeness to God, and as a man who sinks his roots by remaining firmly with his feet in the earth on which he is on his way, always nomadic, this wandering of his becomes a means of knowledge and revelation of his own “diversity,” which as an artist will take him as far as America. Chagall little more than a child draws chickens, barnyard animals, dogs and pigs, but also men and women who seem to spring with great naturalness and truth from his hand, like a spontaneous fruit of the earth, thus participating in its essence in the secret of life that belongs to the arboreal and animal world.

The unity of the living returns in Chagall until the last day of his existence, and serving as a backdrop to the painted scenes is either the facades of the village houses or a bouquet of roses that seems to have the same function as certain garlands in the religious paintings that the Jesuits had promoted by spreading a Baroque iconography where the language and colors of the flowers could also constitute a secret cipher of the theological truths in which the faithful were reflected. What emerges in Chagal’s paintings of the mature age, that is, after the last war, is a form of primordiality that, excluding brutalism, communicates to us that truth that prehistoric rock forms sometimes have. Chagall has within him, even as a boy, the demon of lightness that drives him to dream, to see in the loss of gravity the very way to make bearable an existence where everyone must try to preserve his own good, a form of mild irony that does not want to ignore the tragedies that accompany existence. Oneiric Chagal, an almost gypsy lover who in the violin and dance finds a counterpart in his own biblical way, thinks that the scents of Paris, its fabrics and the feminine that make it the capital of pleasure and luxury, with its thousand turn-of-the-century lights, is a place altogether like a funfair, in essence something as unreal as paradise.

He had begun to hear about it in his early twenties when he decided to go and live in St. Petersburg, soon ending up under the malleolence of the Ballets Russes set designer Léon Bakst, who brought him into contact with the first signs of the European avant-garde. From 1911 Chagall in Paris knew and frequented poets, artists such as Modigliani, the world of cabarets, musicians and singers; it was the time of the Belle Époque, but Expressionism and Cubism had already fired their cartridges and Paris was becoming the theater of the new art whose reflections were affecting other European cities. After a few years, on the eve of the Great War, he returned to Vitebsk via Berlin, but the outbreak of the conflict would later prevent him from returning to Paris. Devoting himself to developing what he had learned in the French capital, as the October Revolution came to fruition he would receive a few assignments as government commissioner for Fine Arts; soon, however, he would fall into disagreement with equally gifted artists, for example Malevič, who in strenuous opposition to the figurative advocated a radical abstractionism to which he would give the name Suprematism (but having overcome this phase, which somewhat simplistically one is wont to call abstract - is there not also a form of abstraction in the figuration of icons to which Malevič looks to as the prototype of his idea of painting? - -, even for the creator of “white on white” is opening a phase of figuration-abstraction that definitively interprets in the architectural value of color and plastic forms that idea that the icon had sublimated within the mysticism of Orthodox Christianity).

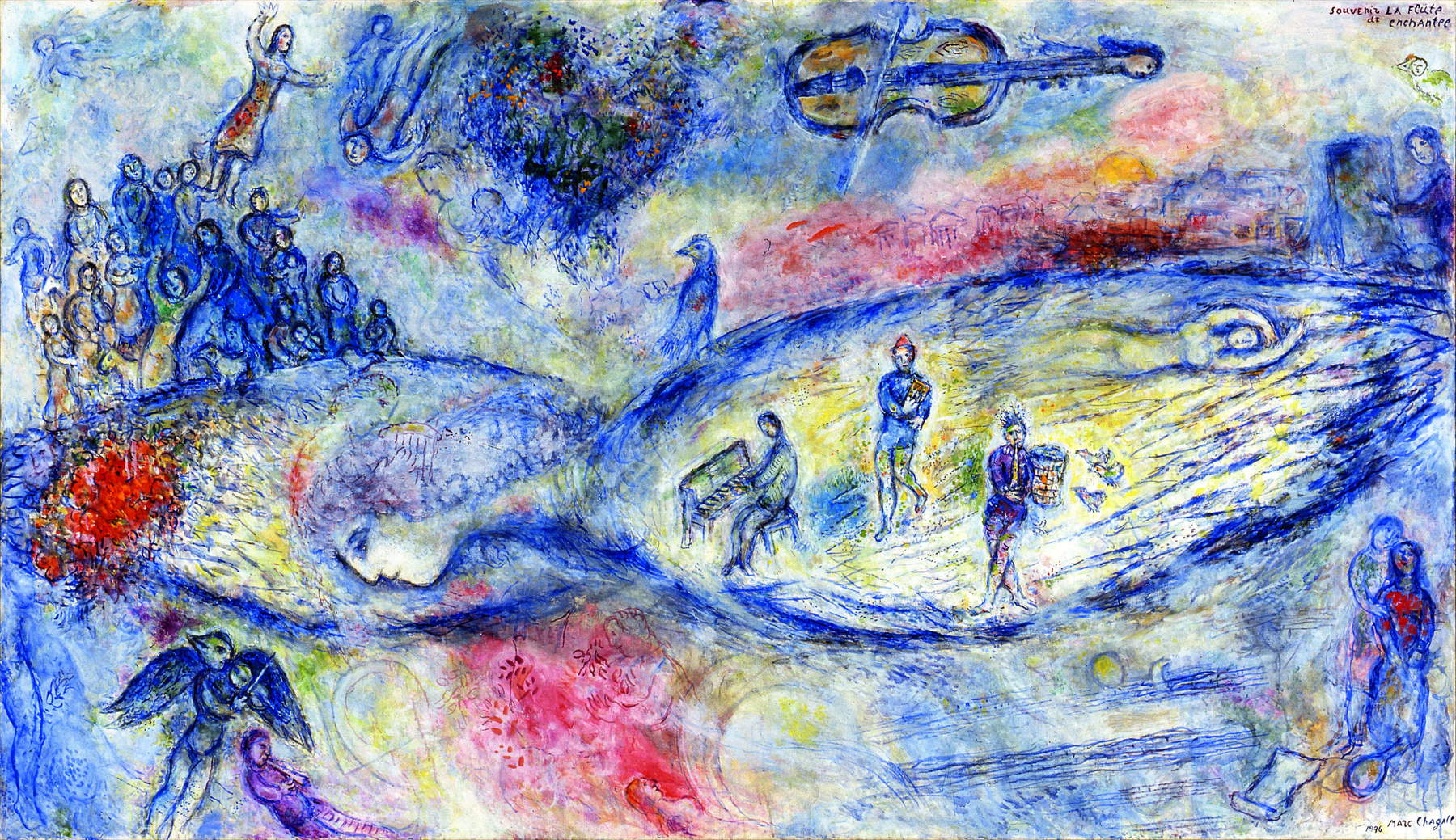

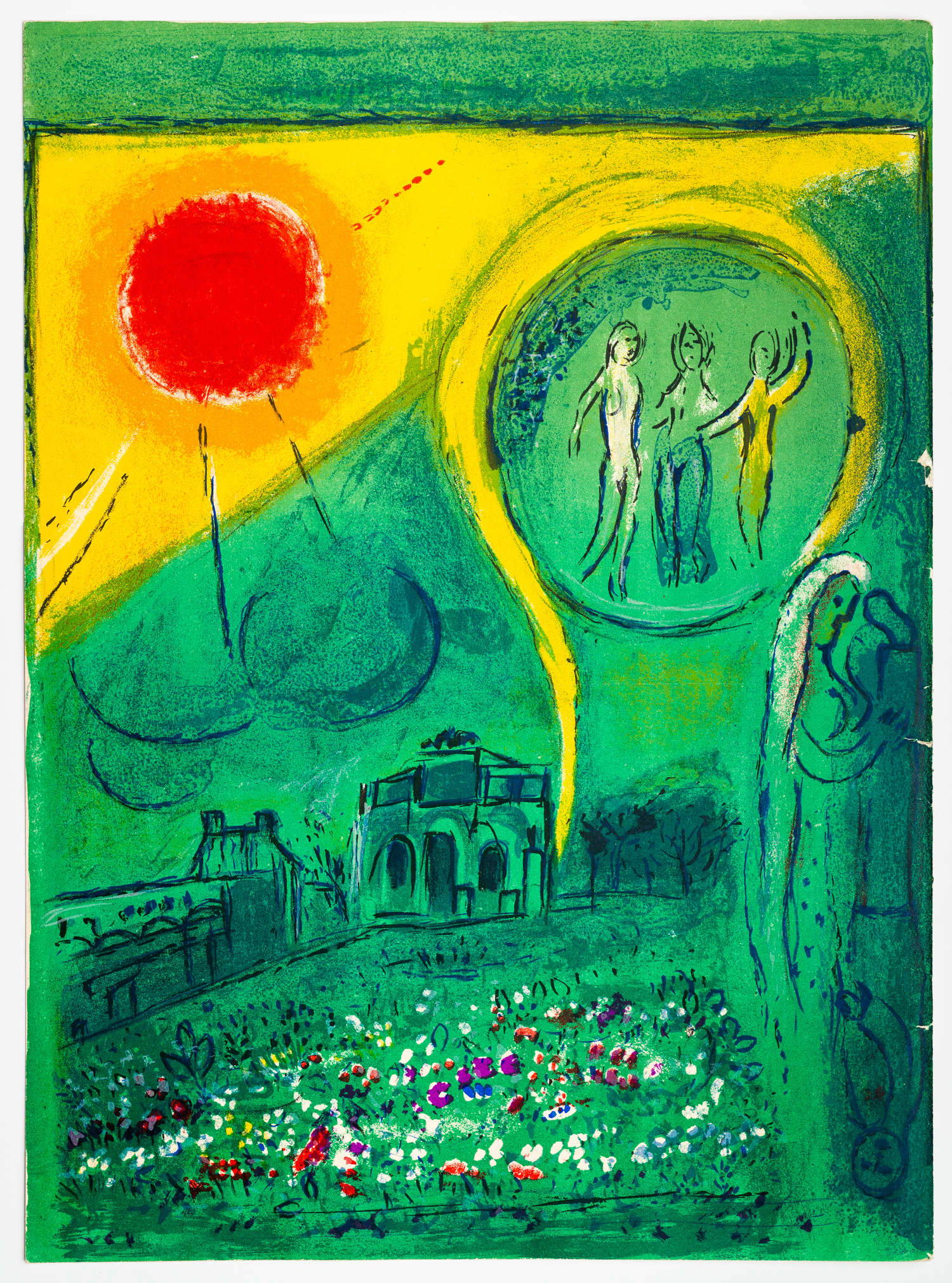

Chagall is not an ascetic temperament or even a political interpreter of the function that art should play in society; he believes only in his own ability to see forms come alive in chromatic matter and light. Thus the developments paving the way for Sovietism prompted him to distance himself from all institutional assignments, leave the public scene and close himself in creative silence (for example, in Moscow, as a set designer for the Jewish Theater), determined by now to return to Europe, to Paris, where ’modern art enjoys a freedom that in Russia is instead sacrificed to the imposition on the horizon of a “realism” that sacrifices individuals to the primacy of state and government and certifies ideological falsehood. Chagall’s iconography thus evolves more and more in a direction where pictorial elegance, reality sublimated within an Edenic vision in which he wants to mirror himself as if by now only a world sweetened and saved from its tragedies could represent thelast mission (in the second half of the twentieth century, now far from Russia and increasingly rooted in his second homeland, France, scenes with roses, trees, shapes rising to the sky and tinged with blues and greens are repeated, as in the twelve lithographs dedicated to Nice and the French Riviera in 1967). The inner context is where for Chagall life and communion take shape between individuals on whom a transfigured sharing of religious faith in the God who is yes the Jewish one, with all the typical Israelite symbolism, but within a West that identifies more than ever with Christianity at the time. But speaking of the use of Jewish symbols, for example, the Menorah, the seven-armed candelabra, or the tallèd, the ritual shawl worn by males during festivals and in morning prayer, we see him girding Jesus on the cross in the White Crucifixion, a key work of 1938, of such expressive density as few other works by Chagall, which reinterprets a much-studied theme today, that of the Jewish Jesus. The fidelity to Judaism of an artist who now also felt himself part of the Christian West is witnessed by presenting the bill to be paid to a society that was staining itself with the most terrible of crimes by transforming the Jewish Jesus into the sacrificial symbol of its people: at the foot of the cross we see precisely the Jewish candelabra and on the crucifix the tallèd.

The exhibition that has been running for several weeks at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, curated by Francesca Villanti (through Feb. 8) is on the horizon that made Chagall a “witness of his time.” Indeed, Chagall’s strong and romantic character, in a sense, allowed him, as Vittorio Sgarbi writes in the brief opening note, to resist ideological and political temptations. When we think of the tragedies and crimes that totalitarianisms have produced in Europe in half a century of action (but it must be said that it is perhaps even more disgusting to see the misdeeds committed by democracies today), it is not surprising that Chagall kept his distance from politics while not disdaining, when ’occassionally, its flattery and commissions, and this I believe was also due to his convinced adherence to the Israelite religion as a bulwark in the confrontation with the Christianity that is measured against that Christianity that has formed the West for two millennia. And when he declares, as if about to pass through customs, the cultural baggage of his origins, Chagall cannot help but remember what he brought with him from Vitebsk: animals, figures and houses of his homeland, to which, he adds, that on that personal heritage Paris has since laid over the light; in saying this, he claims the truth, but it is precisely this truth that, on the one hand, earns him theadmiration as a painter, and on the other makes him the failed stenographer of the soul he began to become as a boy in his “primitive” drawings, which a few decades ago, a rare occasion, were exhibited in another Italian anthology. The vibrant dryness of those graphic signs had the power of an electric wire where glowing tungsten ignites the life of forms. Sgarbi again writes that as an exile - Chagall was at least twice, fleeing the tragedies of the 20th century and finding acceptance even in America - “he did not see, he remembered”; but we know that remembering is the first divine admonition addressed to the Jews: “Remember Israel.” Chagall made of it an additive of memory that holds together the materials of his painting and the forms he was able to centrifuge from the avant-gardes he knew by extracting from them a new irregular geometry and a clot of free forms anchored in the history of twentieth-century art and reread within an open confrontation with “modern” ideas that have sometimes been antagonistic to each other. Here, this synthesis in a new imagery, properly his own, is also a form of that pacification that Chagall invoked for man and human communities.

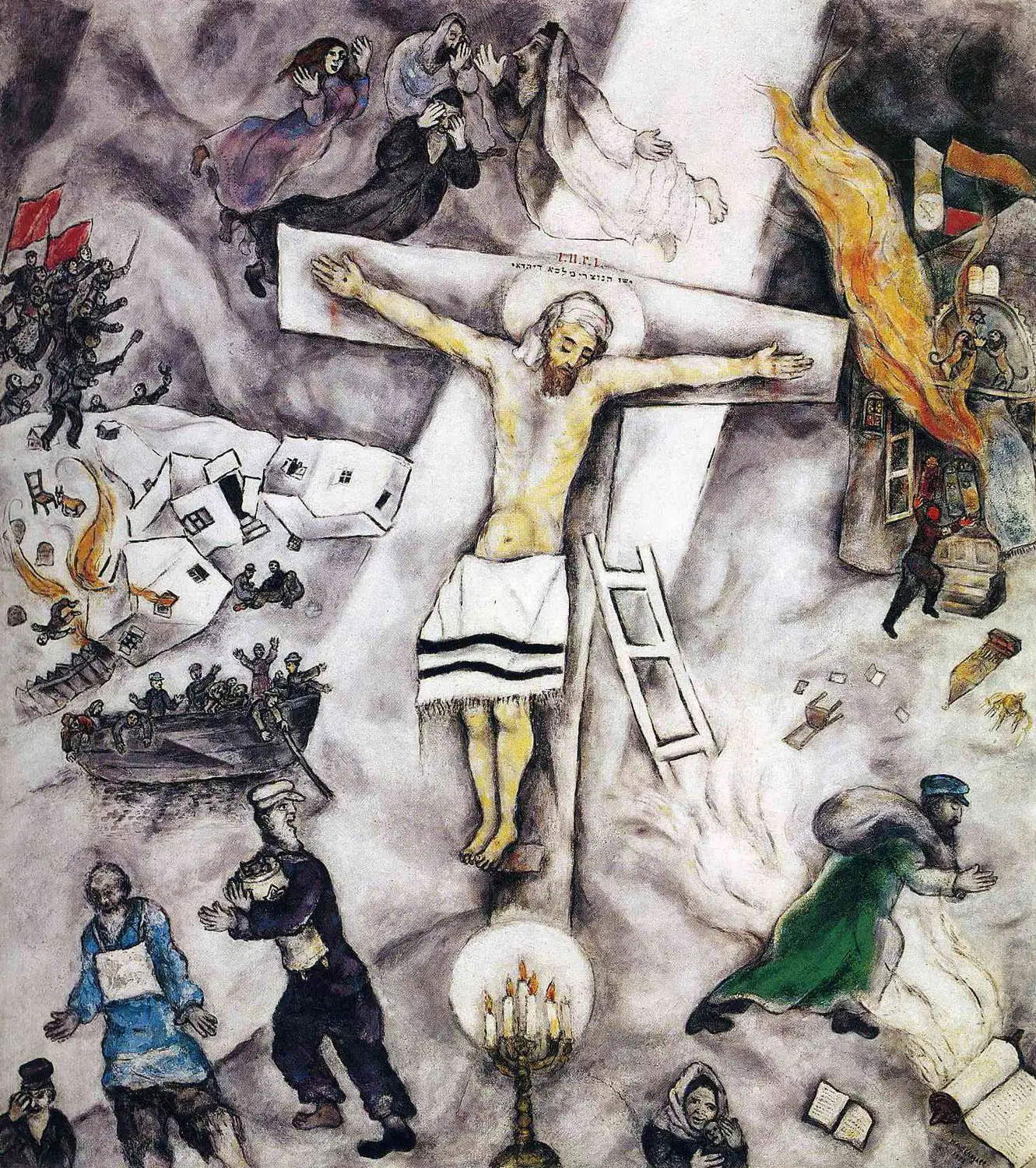

The Ferrara exhibition, much publicized far beyond its actual aesthetic qualities, which are quite questionable despite the more than two hundred works on display, offers no great jolt of tension within itself. Two-thirds of the works are etchings and lithographs, and the oil works are mostly dated from the mid to late twentieth century onward.Overall, the materials on display are all from private collections, which could mean that there is also an intention on the part of the owners to sell some of the works on display. But we can say without mistake that none reaches the rank of such an epoch-making work as The White Crucifixion. Paradoxically, playing a bit with “synonyms,” we could say that the exhibition does not have all the trappings of a retrospective, at most it can be called an anthology with materials of a very very heterogeneous collected with uneven criteria, or at any rate affected by an iconographic monotony that does not procure true élan vital (in some respects, the exhibition Chagall in mosaic that closes in a few days, on January 18, at the Mar in Ravenna, is more coherent and interesting: in the mid-1950s, Chagall had the revelation of this art while visiting the Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna, and began to produce works, one of which is precisely preserved in the city of Romagna).

The series, this one really beautiful and moreover also much seen, of etchings devoted to La Fontaine ’s Fables, achieves a painterly strength, so to speak, thanks to the very refined technique that sums etching and drypoint, testifying to the achievement in Chagall of a very French style. What would have really taken us aback, however, would have been to see exhibited the sketches that Chagall executed at the very beginning of the twentieth century, which we mentioned at the beginning, where the young artist portrays, as if etching on his own skin, the rural world of Vitebsk. Such a powerful rendering of reality that it prompts us to say that perhaps the whole chalcographic world that Chagall left us afterwards descends at various layers from the psychology contained in those early drawings that tell even then where the pure soul of the painter is hidden; one may wonder if the very young Moishe training in the fine arts, still far from turning into Chagall, had not heard of the idea of folk art that Tolstoy was addressing at the time intime in a specific small volume, famous and widely read pages even outside Russia, which the great writer published in 1897; and if he had not combined with those ideas the knowledge of a certain type of popular Russian folk prints widely spread among the people (some were even used to wrap fish and meat in them) called Lubok, which told very well-known fables and myths of the Russian tradition, now rediscovered and studied. Faced with this possibility, one should therefore study the extent to which Tolstoy’s ideas and folk prints affected the artistic growth of a painter at that time little more than a teenager.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.