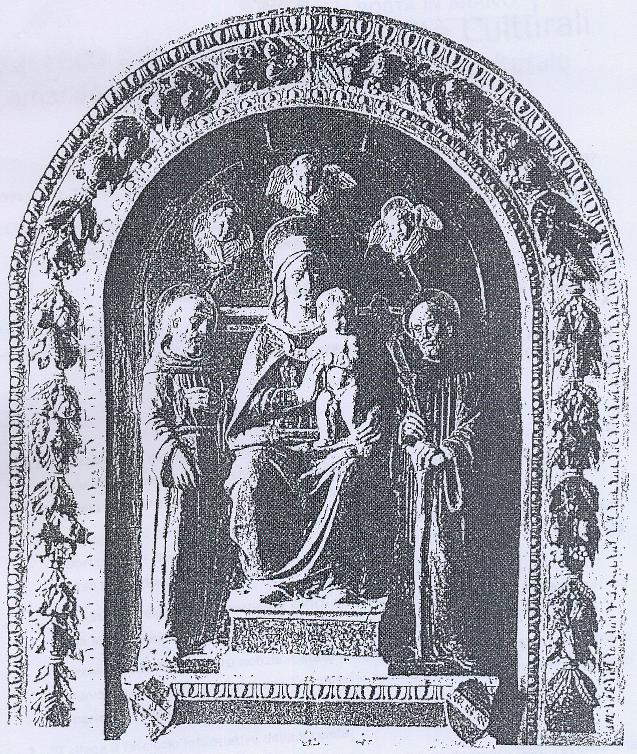

The case of the Madonna and Child with Saints by Benedetto Buglioni (Florence, 1461 - 1521) from the Cleveland Museum of Art is being discussed again, after a group of parliamentarians brought the matter to Parliament in the summer of 2020 ( we had reported on it in a dedicated article). It is a beautiful glazed terracotta that, at least as early as 1749, decorated a tabernacle in Ponte agli Stolli, a placid village nestled in the Valdarno woods, along the road connecting Figline Valdarno (of which it is a hamlet) to Greve in Chianti. Then, in 1905, it was stolen: the alleged perpetrators of the theft were put on trial in 1906, but traces of the work were lost.

However, in 1921 an American financier and philanthropist, Jeptha Homer Wade II, donated it to the Cleveland Museum of Art after purchasing it that very same year from the Galerie George Petit in Paris through the intermediary P.W. French & Co. Previously, the work had belonged to German antiquarian Raoul Heilbronner, from whom the French government, during World War I, had confiscated it. Now, however, the work by Benedetto Buglioni turns out to be included, with code 87709[1], in the database of illegally stolen cultural property of the Carabinieri’s Cultural Heritage Protection Unit: the glazed terracotta is listed with an old black-and-white photo, where, however, it is clearly recognizable.

The case became topical again after statements by Senator Margherita Corrado (now in the Mixed Group), who in 2020 had addressed, with eight other colleagues, the parliamentary question to Culture Minister Dario Franceschini. The process of the question still appears to be open, but no response has come from the minister. “The July 2020 question, now almost two years ago, has remained unanswered,” Corrado said, “but the case, however ’cold,’ is not closed, and much could still be done to illuminate an affair (the May 11, 1905 theft) that has remained well in the consciousness of the local community. Pieces of History and memory snatched from the living body of the country that the justly vaunted Italian cultural diplomacy does not claim with the necessary determination. Fortunately, the local press (Valdarnopost.it) does not forget.... ”.

This time, however, many are also talking about the affair in the US. Cleveland-based News 5, part of the ABC network, devoted a report to the case. “It was taken away illegally, you cannot deny it,” Italian art historian Victor Veronesi told News 5. “It is impossible not to say that this work is the one from Ponte agli Stolli. It was the heart of Ponte agli Stolli.” The newspaper, however, denies that the Cleveland work is the same as the one featured in the Carabinieri photograph: “a closer look at the two works shows that they are very similar, but they are not the same. For example, the Madonna’s face looks at the Child in the sculpture exhibited [in Cleveland], while she looks much farther away in the historical photos.” Of course, the mere comparison of the photographs is not a sufficient condition to rule out the possibility that it is the same work, given the very poor quality of the historical image, which is very grainy and has strong contrasts that give the perception that the Virgin’s gaze is looking away. In addition, it is not excluded that the work was altered later, as speculated by Veronesi, who concludes by saying that the theft of the work “is and still is a great loss for the population of Ponte agli Stolli.”

Senator Corrado now calls for work to get the work back: a push could come from the Valdarno community, which would see the return of an important work from the area. Meanwhile, no comments are coming from the Cleveland Museum of Art, as is the practice when there are no official requests and when there are ongoing discussions. In the event, however, that it is confirmed that the Cleveland work is the one stolen in 1905 and a request for its return is made to the museum, there would be cooperation from the institution: in fact, this would not be the Cleveland Museum of Art’s first return to Italy. Already in 2008, in fact, the institute had returned 14 pieces stolen between 1975 and 1996, while in 2017 it rendered to Italy a marble portrait from the Roman era stolen in the Naples area.

|

| Spotlight shines on the case of the 16th century terracotta stolen in Valdarno in 1905 and now in the U.S. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.