It may sound strange, but it has been thirty years since Nicolas Bourriaud, it was 1996, began to establish the contours of his very successful “relational art” formula, and until today no one, before the exhibition that invades the second floor of the MAXXI in Rome until March 1(1+1. Relational Art), had ever devoted a review to relational art that took into account the entire path taken by the practices identified by Bourriaud and made by him to fall under the admittedly rather broad definition of an art “that takes as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the affirmation of an independent and private symbolic space” (so in his 1998 book Relational Aesthetics ). Of course, one could argue against Bourriaud (as has been done, for that matter) that art has always been relational, in the sense that a work of art, except in very rare, and in any case irrelevant, cases, always presupposes at least a relationship between the producer and the observer (but even imagining an artist producing for himself, the work of art cannot disregard a relationship with a context): however, this is not the point, since Bourriaud himself is aware of this and since his battle cry is actually more circumscribed than one might think, and concerns those works that elevate the relationship and theencounter between viewer and image to the core of their meaning, those works that deliberately intend to bring out, and sometimes even orient and condition, a space of encounter between its recipients, or those works that, on the contrary, arise or develop from a relationship between human beings, or between human beings and the object. Wanting to follow the filtration of the apparatuses that accompany the public along the halls of MAXXI, relational artists have begun to consider the object as the single element of something larger, and the creation as a moment that goes beyond the workshop process and continues when the object is put in front of an audience.

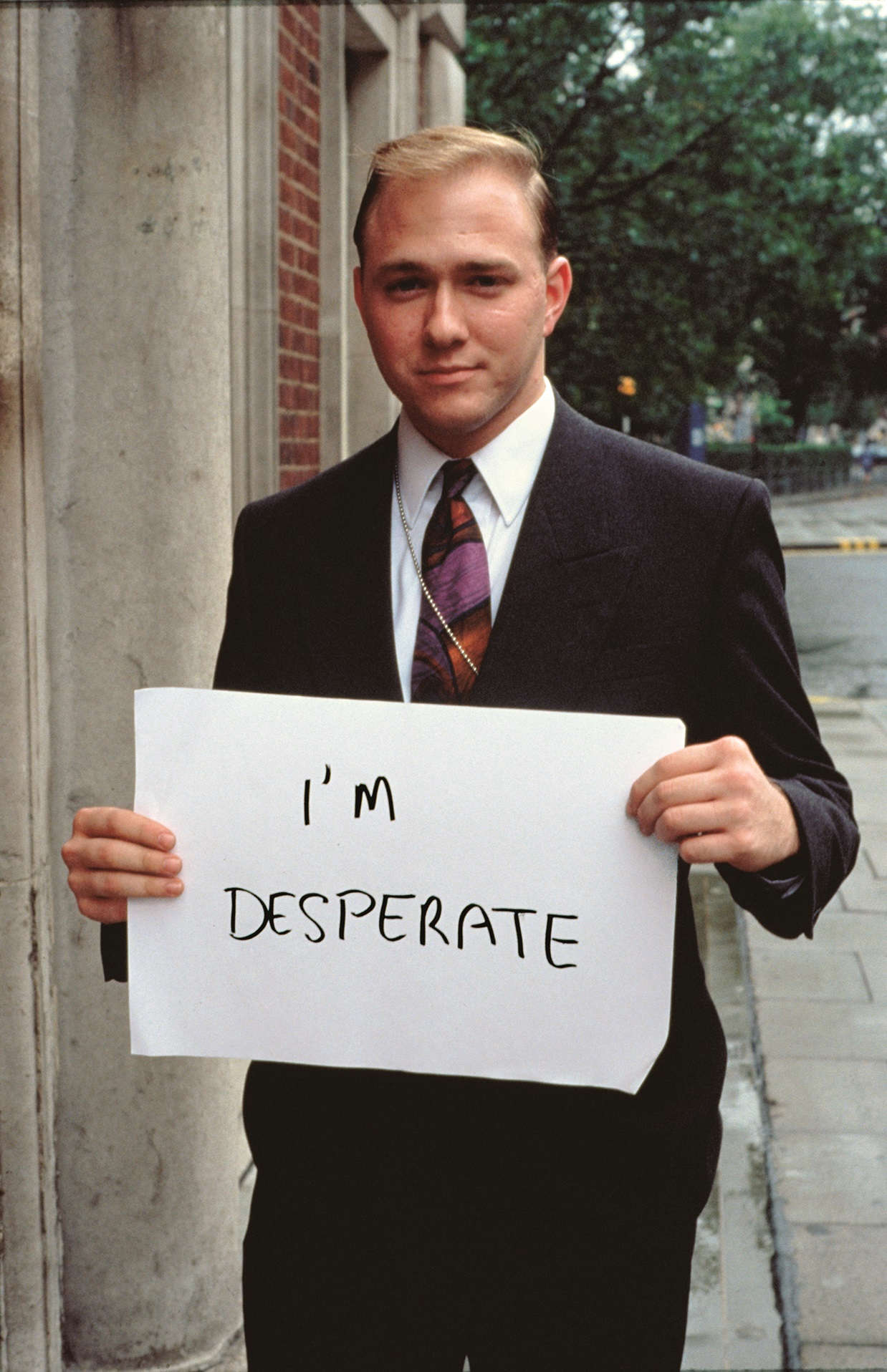

There are, in the exhibition, all the examples of the three rudimentary cases just mentioned. In the first case we are still on the level of the viewer-object relationship, but the relationship presupposes the presence of an active participant who becomes the very material of the work, since without the relationship the object would remain merely inert matter: this is the case with Carsten Höller’s Love Drug , a small bottle that is held between two fingers but activates one of the most intense physical experiences one can have inside a museum and probably even outside, and which will accompany the visitor throughout the exhibition and beyond. The bottle contains a chemical compound based on phenylethylamine, often associated with states of euphoria and happiness (they call it “the molecule of love”), and Höller invites visitors to smell it (the smell is extremely pungent, and it lingers) to shift the relationship with the object from the aesthetic to the physiological plane. And perhaps even to enjoy seeing the effect it causes on other visitors. For the second case, one can summon Gillian Wearing with her project Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say, a long and yet effectively self-explanatory title: the British artist, between 1992 and 1993, photographed hundreds of people who were asked to hold up a sign with their own thoughts written on it. The result was a gallery of images that were at times lighthearted and cheerful, just as often poignant, troubling, disturbing: the work, one might say, arises from an encounter between artist and subjects and develops in the further encounter between subjects and recipient. Finally, to find an example of a work that arises from a relationship between human beings and objects, one could not help but think of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s celebrated Candy works ( A corner of Baci is on display in the exhibition) without the action of the public who, by taking away a candy or a chocolate, loads the work with its meaning.

Perhaps Bourriaud’s happiest insight was to have assigned, moreover arriving at it empirically, an unprecedented weight to relationship, which could even be considered a dimension of the work of art: if the Futurists had conquered a fourth dimension (movement) and the Spatialists the fifth (time), then it might not be far-fetched to think that relational artists had arrived at the sixth (relation, precisely). Bourriaud understood that, having arrived at a given moment in the history of art, the object no longer enjoyed a condition of self-sufficiency: if a painting exists without the viewer, the works of relational artists do not happen unless an interaction is given. Cattelan’s works (on display, for example, is a photograph of the 1999 action Untitled , in which the artist attached his gallerist Massimo De Carlo to a wall) would not make sense if deprived of the audience’s reaction, which is an integral part of the creative process. Without the estrangement it causes on the audience, Philippe Parreno’s Christmas tree would be just a decoration. Without its surprising interior space, the Opavivará grove, one of the works created for this exhibition, would be just a pile of plants out of context. It is natural, at this point, to note that since the time of the Dadaists there have existed artistic practices based on relationship as an element of the work: the happenings, the Situationist International, everything that falls under the umbrella of performance. Bourriaud intended to place his relational art at the end of the line that unites all these experiences, identifying the artists active at the turn of the century as a “group of people who, for the first time since the appearance of conceptual art in the mid-1960s drew no nourishment from any reinterpretation of this or that aesthetic movement of the past”, and understanding intersubjectivity and interaction not as a “fashionable theoretical gadget” or even as an “additive (alibi) to a traditional art practice,” but as “the main informants” of the activity of artists who can be identified as relational. That is, artists who move in the “space of interaction” and produce “relational spatio-temporal elements, interhuman experiences that seek to free themselves (in a sense) from the straitjacket of the ideology of mass communications, from the places where alternative forms of sociality, critical models, and moments of constructed conviviality are elaborated” (so in Relational Aesthetics). In short: the idea is that if in earlier art practices there was still a clear boundary between the artist and the audience, in Relational Aesthetics the artist becomes a kind of facilitator (on the modes of production, Bourriaud would later return with another of his successful titles, Postproduction: here it will suffice to simply recall that for the French critic, art, from this point of view, is an “assembly bench of reality”). Bourriaud, in essence, has conceived an art that poses itself as a producer of new social ties, a creator of spaces of conviviality, of micro-utopias (although the goal is not to imagine alternative worlds, but to propose, if anything, models of action for what Bourriaud calls the existing real in order to learn how to better inhabit it). In this sense, the work of art is for him therefore to be understood as a “social interstice,” where the term “interstice” is taken from Marx who used it to refer to commercial communities capable of escaping the capitalist economic context (barter, autarkic forms of production, and so on): similarly, for Bourriaud the relational work is a space in human relations that fits “more or less harmoniously and openly into the overall system, but suggests possibilities of exchange other than those actually taking place within it”, with the aim of “creating free areas and intervals of time in which the rhythm contrasts with those that structure daily life, and encourages interhuman commerce other than the ’communication zones’ that are imposed on us.” A few more examples from the exhibition: the famous action Untitled 1990 by Rirkrit Tiravanija, who in a New York art gallery prepared and served visitors a typical dish from Thailand, his home country. Another action, My Audience, by Christian Jankowski, who since 2003 has still not stopped photographing the audience attending his lectures with the intention of probing, and somehow reversing, the dynamics created between the speaker and the audience during such occasions. Or Alicia Framis’ transparent Confessionarium : a confessional where the admission of sins takes place before anyone walking through the exhibition and becomes, the panel in the room informs us, a metaphor for the need for truth and for overcoming the hypocrisies of religious power.

This is not the place to measure the scope, coherence, felicity, and originality of Bourriaud’s ideas, which although widely popular today have also generated debate and have inevitably received some important critical responses. However, it is worth mentioning some of them: Claire Bishop, for example, questioned to what extent the “structure” of a relational work can be detached from the apparent object of the work or how permeable it can be to its context, and how measurable the relationship produced by a work of art can be (“the quality of relationships in relational aesthetics”, he wrote, “is never examined or questioned,” because dialogue and exchange are assumed to be inherently good when in fact, according to Bishop, antagonism should be the key to rethinking our relationship with the world and with others, since without conflict and dissent the work would risk being superficial or complacent). Grant Kester, on the other hand, accused Bourriaud of confusing the aesthetic dimension of art with the political dimension, since, in his view, the most problematic aspect of relational art’s discourse is its substantial resignation, evident when therelational artists’ experiences remain disconnected from concrete change or actual political praxis (“the result,” Kester wrote, “is a crippling quietism that decisively separates this prefigurative-generative knowledge from any connection to praxis here and now”). The work would thus continue to act on the aesthetic, or at most the symbolic, level without translating into concrete action, into structural challenge. One could then disagree with the idea of a relational art that does not reinterpret movements of the past, when it is difficult not to perceive it as the child of all that preceded it. One might dispute the interchangeability of the term “relational” (some have spoken of “interactive” or “participatory” art to describe essentially the same experiences, a criticism moreover disputed by Bourriaud himself in the catalog: for him, participation is one of the tools of the relationship, but it is not the subject of relational art). However, this is not, it was said, the place to test the validity of Bourriaud’s assumptions: however, one could limit oneself to at least one aspect that is also useful for evaluating the exhibition. That is, one could contest, on the one hand, the self-referentiality of much relational art and, on the other hand, above all, the fact that much relational art is born and developed within an official system that is itself self-referential, closed, detached from the world, to come to the conclusion that relational art does not have all this potential for change that could be attributed to it in the abstract (or, if it does, perhaps it is a mediated potential). The universality of the content clashing with the elitism of the container.

No one, of course, forbids imagining the museum as a laboratory, nor is it intelligent to think that all of humanity must pass through a museum or gallery in which a relational performance is consummated: the potential of a participatory work is above all the indirect one, lies in its ability to filter outward through more or less broad forms of mediation (architecture, activism, cinema, urbanism, politics itself). Matteo Innocenti provided an extremely fitting example in his review of the exhibition published on the Antinomies blog: Kimsooja’s work A Needle Woman , which the public finds at the MAXXI opening (the Korean artist, between 1999 and 2001, traveled to Tokyo, Delhi, Cairo, and Lagos and began to be filmed standing motionless in the midst of the crowds passing by her) is paralleled with the actions of a young Turkish choreographer, Erdem Gündüz, whose standing man protest between 2013 and 2014 became a symbol of dissent against Erdoğan’s government. Nor is it disputed that an opera or exhibition can change the world in a small way, perhaps by only two people: the goal is not to ensure mass conversions for the public, but to provide tools. However, neither can we underestimate the risk of having in our hands objects that speak only to those who are already well-informed, and the MAXXI exhibition in some ways does not seem to disregard this direction, at least in its basic construction, its structure. Meanwhile, 1+1. Relational Art is presented as a “retrospective,” another problematic term that is often used to classify everything. In the introduction to the catalog, however, Francesco Stocchi presents it as an exhibition that “proposes a comprehensive investigation of the origin, development and evolution of relational art by interweaving works from the 1990s with research from a later generation, extending the field of inquiry beyond the Eurocentric horizon that had characterized its first theoretical formulations.” However, it lacks an appropriate historical slant: if for those who have some knowledge of the subject it is easy to identify an even minimal structure within the path imagined by Bourriaud, although the linearity of the construction is often sacrificed, also because of a space that does not leave much room for maneuver (here then come all the “founding fathers,” let’s call them that, then the projects in fieri and their precursors, then again all the artists who anticipated relational art, including Maria Lai with her Legarsi alla montagna, here and there the most recent works and those created for the occasion: The Piombino Group is missing, though it is given space in the catalog), the public who does not know what has happened in the last thirty years of contemporary art risks being left to their own devices. To guide the visitors, some questions have been put in the captions (for example, under Cattelan’s Hollywood : “If you could choose a place to install a famous and iconic inscription with the same provocative spirit as the artist, which inscription and which place would you choose?”, or again, under Vanessa Beecroft’s VB74 : “In the contemporary world laden with high-definition, often edited images, has the way we relate to flesh-and-blood bodies changed?”). A tool that arouses sympathy, but which on the one hand is also very middle school textbook-like, with all the attendant consequences (one above all: the intent to make the captions of the works relational as well is totally understandable, but neither do we feel like excluding the possibility that even a more adult approach would have allowed for equally and perhaps even more in-depth), and on the other it almost seems to replicate the interaction modes of generative artificial intelligences such as ChatGPT and Gemini that, having finished explaining a concept to you, pepper you with questions: the difference is that there is no one at the show willing to replicate you with the same loquacity as the machine (could this be the cue for a relational artwork?). Today we ask too many questions, but we remain without answers, without references, without fixed points in a world that is increasingly fluid and difficult to understand: here, perhaps an artist today should fill precisely this void.

In any case, one gets the perception of visiting an exhibition designed and built mainly for insiders, a sort of best of, an anthology of what has happened in thirty years of relational art, although there is enough material among MAXXI’s open rooms to reconstruct a structured chronology (a task that, however, is still entrusted to the catalog). One could divide the history of Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics into at least three moments: the first one of theoretical elaboration, which roughly corresponds to the second half of the 1990s and lasts at least until the mid-2000s or a little more. Then, a second moment of global diffusion, and finally a moment of “crisis of the human measure,” to use the curator’s own expression, that is, a moment in which the human being begins to lose its centrality in the network of relationships in which artists think of themselves and the recipients of their works. It is a period that begins quite early on (especially with Pierre Huyghe) and lasts until the present time, a time when artists have found themselves thinking about an “environment composed of subjectivities (human, animal, plant... ), an ecosystem in which there are only subjects [...], made up of infinite relationships” (the turning point, in Linda Motto’s very detailed chronology in the catalog, is attributed to Carsten Höller’s Soma , a 2010 work with which the German artist constructed a scenario of connections between humans, animals, chemical and biological substances). If, however, the first and second moments are well documented in the exhibition, since they represent the bulk of the material assembled by Bourriaud, the documentation of more recent developments is more lacking: it must be said, however, that given the space available, and also given the difficulty of the MAXXI’s environments, which lend themselves poorly to a review constructed with traditional tools, methods and paths, it is also very difficult to imagine an exhibition organized differently. Not least because the world has changed at a speed perhaps greater than how relational art has changed. Nevertheless, the exhibition remains a useful anthology, summing up many of the most interesting moments of the “movement” defined by Bourriaud and offering the public a historical perspective of certain interest.

There would also be no shortage of opportunities to reason about the present of relational art (there are many artists who continue to produce within the furrow traced by Bourriaud: he himself, in an interview granted to Finestre sull’Arte, stated that his ideas are still alive and there are several young artists who recognize themselves in these ideas) and, above all, about the impact that relational art has managed to exert. It would be worthwhile to dwell on at least a couple of unquestionable effects of the relational movement by reasoning about a couple of cues in the catalog. The first is offered by Bassam El Baromi, when he says that relational aesthetics has been able to enhance “the social, human and networked relationships that works are able to produce as horizons of possibility, rather than relegating art to the traditional object-subject correlation.” This does not mean that in the 21st century the work of art no longer has to be a painting or a sculpture, but it does mean that art can also be understood as a dynamic process that involves communitieseven if only for a short time, and so much of contemporary art has, moreover, turned toward processes that encourage participation, the invasion of public space, and the transformation of art venues themselves into laboratories.

The second cue comes from Sara Arrenhuis’ essay, “One aspect of the practice of relational aesthetics in contemporary art that stands out in retrospect today is that it prefigures and anticipates the commodification of social interaction that dominates our current culture.” It is a topic of extreme topicality, even if in the course of the exhibition it remains almost glossed over, or at least does not emerge as prominently. Many relational artists seem almost to have foreseen the arrival of a time that has turned every relationship into a product, measurable and subject to profit logic: the most fitting and clearest example is that of social networks, which are shaping in an increasingly invasive way the way we observe reality, and make a profit not only on our social interactions, but also on our superficiality, our anxieties, our fears, and the content we consume through the platforms. Not only that, relational artists understood well in advance that value would shift from things to relationships, from objects to contacts. The problem is that all those actors who hold and exercise the potential to turn interactions between human beings into products to be traded, with the results we see today, also understood this. Tiravanija’s designed sociability of inviting strangers to dinner in a museum in the 1990s was a path-breaking gesture; today it is the basic mechanism of so many platforms that stand on the commodification of relationships. And if thirty years ago artists were trying to invade the interstices, today the space for those interstices has drastically reduced. The challenge of an art, relational or otherwise, that induces us to think about the quality of our interactions, that expresses dissent, that offers forms of resistance is much more difficult than those that relational artists faced thirty years ago.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.