The austere space of the former Campo Boario in Rome, the industrial archeology of Pavilion B of the Testaccio Slaughterhouse regenerated years ago into a space for contemporary art exhibitions, acquires -again- a dramatic symbolic value by hosting now, and until October 12, Spaces of Resistance. Curated by Benedetta Carpi de Resmini, the exhibition takes the form of a single, large, coherent installation on the memory of the war in Bosnia. And, in the darkness of that distant memory, it sheds light on current conflicts: from the massacres of civilians perpetrated by the Russians in Ukraine to the massacre of the Palestinian population in Gaza by Israel’s army. In Spaces of Resistance, the visual projects of Simona Barzaghi, Gea Casolaro, Romina De Novellis, Šejla Kamerić, Smirna Kulenović and Mila Panić find points of contact and continuous cross-references, according to the exhibition plan devised by the curator, around the history, landscape and people of Bosnia, exactly thirty years after the end of that fratricidal war in the heart of Europe but also exactly thirty years after the genocide in Srebrenica: July 11, 1995. And so it is that the old slaughterhouse in Rome underscores with its mighty, black cast-iron columns the mournful memory of the former Potočari factory, then a UN soldiers’ camp, then transformed by Serbian torturers into a lager for the Muslim population of Srebrenica.

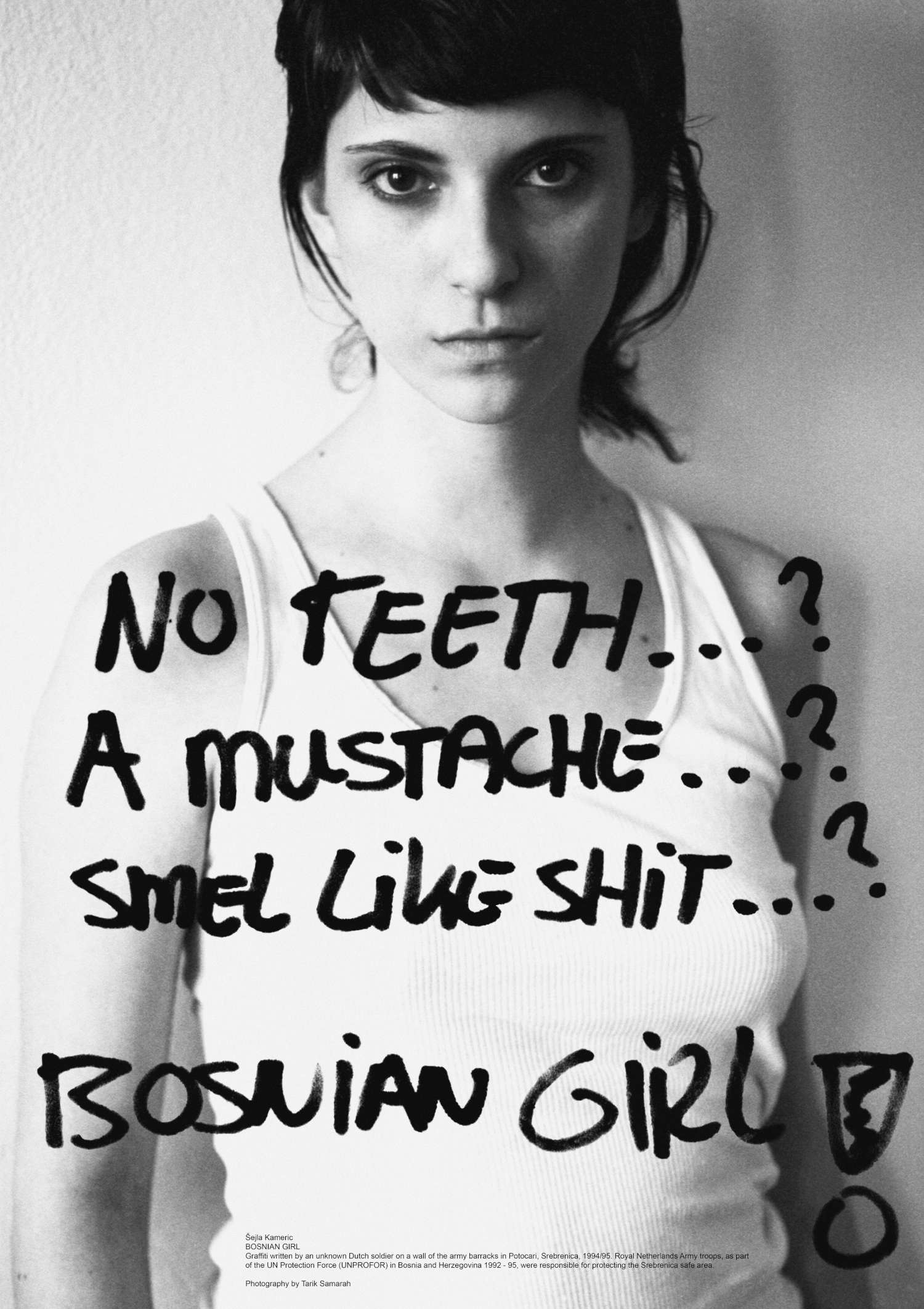

On the walls of that building, when it was U.N. barracks, a Dutch soldier-the military corps that did nothing to stop the genocide of thousands of Muslims by the Serbs-wrote, moreover, obscene, sexist and racist words against Bosnian women. And these are the words that Šejla Kamerić, a survivor of the massacres in Sarajevo, where she was born in 1976, used for her 2003 self-portrait Bosnian Girl. That is, by printing them, like scratches, on her face: “Her direct gaze,” the curator writes in the catalog (Kappabit editions), “denounces the complicity of the male gaze and transforms the offended body into a symbol of resistance and collective memory.” The photo installation is provided by Tanja Wagner Gallery in Berlin. It was in the German capital that in 2004 Šejla Kamerić (featured in the exhibition with five interventions in all) carried out the action/provocation of Frei: printing the word frei (free) on the hands of those leaving clubs. Of that gesture - which replaced the nightclub logo with the word used by the Nazis on the gates of the death camps (“work makes free”) - brass stamps, among other things, have remained. Which, encased in a transparent display case, as if they were jewels, now welcome the viewer who has entered the Spaces of Resistance.

At the opposite apex of the door to Pavilion B of the Slaughterhouse, a cultural space managed by the Azienda Speciale Palaexpo of the City of Rome, stands the mountain of earth that constitutes the site-specific work of Smirna Kulenović, who was born in Sarajevo at the height of the conflict in 1994. Down to Heart invites visitors to stick their heads into one of the three holes in the sort of burial mound that resembles an igloo. With the head in the hole in the earth, but also by staying out of the sound pits, it is possible to hear songs and dirges of old Bosnian women. And these are the voices that have been removed from the video placed there in front, A Seed for a Song (2025), in which the ritual of women’s dance is accompanied by eerie multicolored masks.

Smirna Kulenović’s installation proposal is preceded by two mirrored rooms, to the right and left of the Pavilion, where her papers and stones from Silence of the Land (2024) are placed. These are cellulose sheets and colors made from the plants (such as nettle or rose hips) grown on the earth of the mass graves. No images appear in the monochromes, but knowing that the subject matter of the work is the earth that housed the bodies of so many blameless victims charges this tribute to those who are gone with religious silence. And the quotation in the title of Jonathan Demme’s film-masterpiece(The Silence of the Lambs) only underscores the compassion for the sacrifice of so many innocents, thirty years ago and today.

Land, understood as place of origin but also as matter and material, dominates the exhibition’s palimpsest. Evidence of this is the fact that the third Bosnian chosen by the curator to structure the thematic and political journey of Spaces of Resistance, the young Mila Panic (Brčko, 1991), participates in the project with the 2017 video Burning Field. In the hundred minutes and more of fixed-camera footage, a man appears in the distance, setting fire to the stubble of his field (the only sound commentary, the crackling of the flame carried by the wind). It is the Panic family’s farmland being burned to regenerate crops. And this ancient and common practice is mirrored in the exhibition, through a video of disarming simplicity, at the flower garden of the mass grave evoked in the works of Smirna Kulenović who, author in 2021 of Our Family Garden, writes in the catalog, “We are sitting on a carpet, eating Bosnian pita in a field of dazzling yellow flowers. I say to my grandmother, ’The flowers - they are too strong. I see ghosts in the ground.’ She smiles, shaking off my childhood fear. ’The war is over, dear,’ she whispers. A few years later, I will be asked to identify my uncle’s body, forgotten, buried under our field of yellow flowers. ’A mass grave? It can’t be here. It’s where we come for picnics’.”

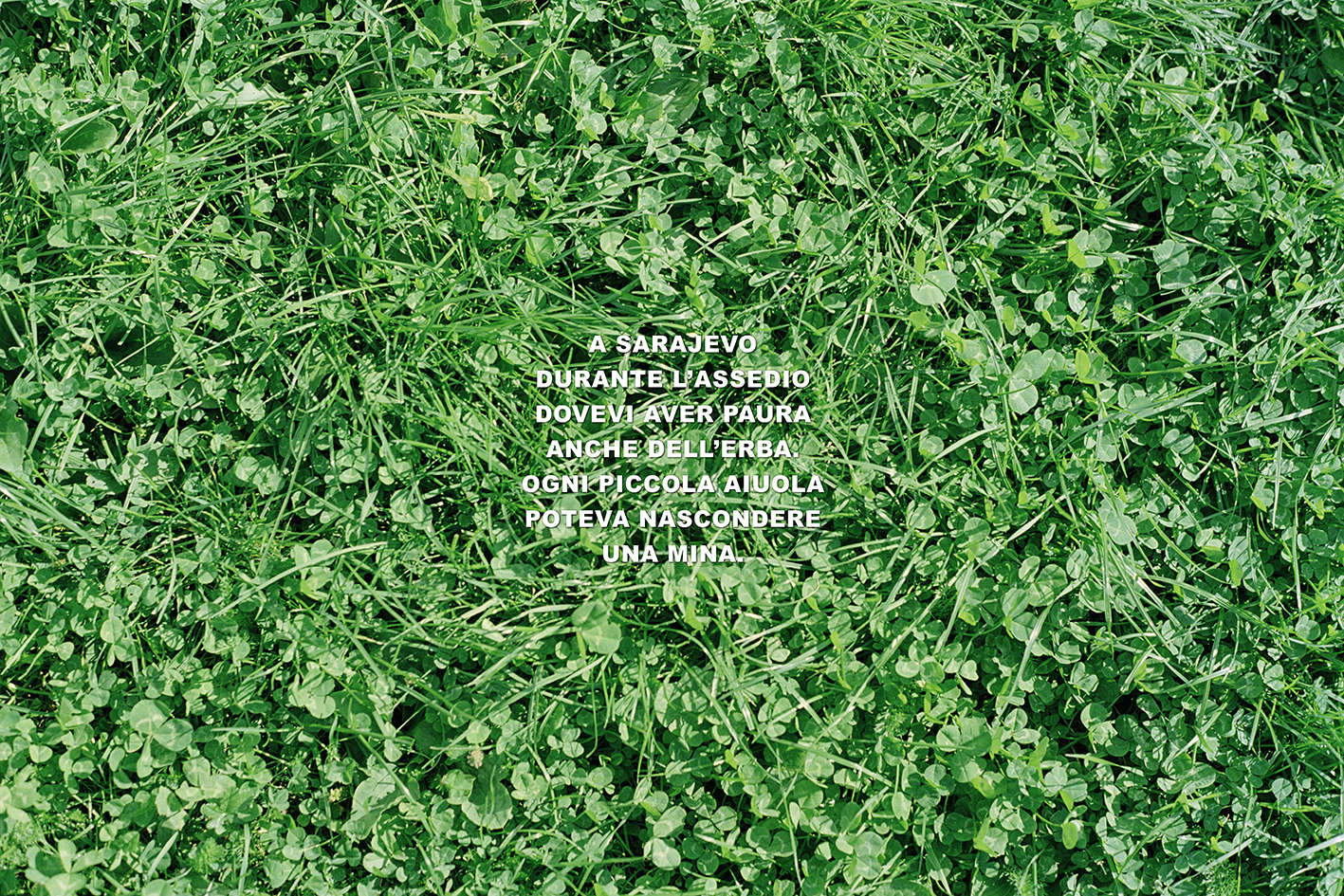

The burnt dry grass in Mila Panic’s video placed at the end of the exhibition is contrasted with the green, urban grass photographed by Gea Casolaro. Having arrived in Bosnia in 1998 to participate in the Biennial of Young Artists of Europe and the Mediterranean, Casolaro, from Rome, born in 1965, created among other things L’erba di Sarajevo#2: 60 sheets of paper all the same that, on two walls of the Slaughterhouse, now repeat the phrase heard by survivors of the extermination and transcribed on a computer: “In Sarajevo during the siege you had to be afraid even of grass. Every little flowerbed could hide a mine.” The repurposing of that work, dated 1998-2025, seems to stand for the fact that that warning is still valid, the deadly danger still lurking, decades but also a few thousand kilometers away.

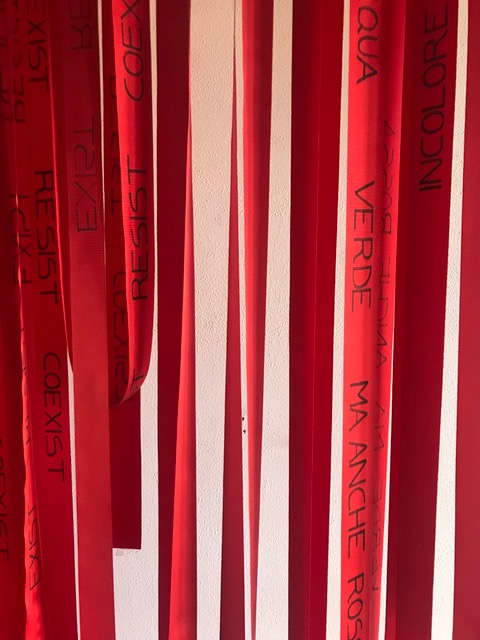

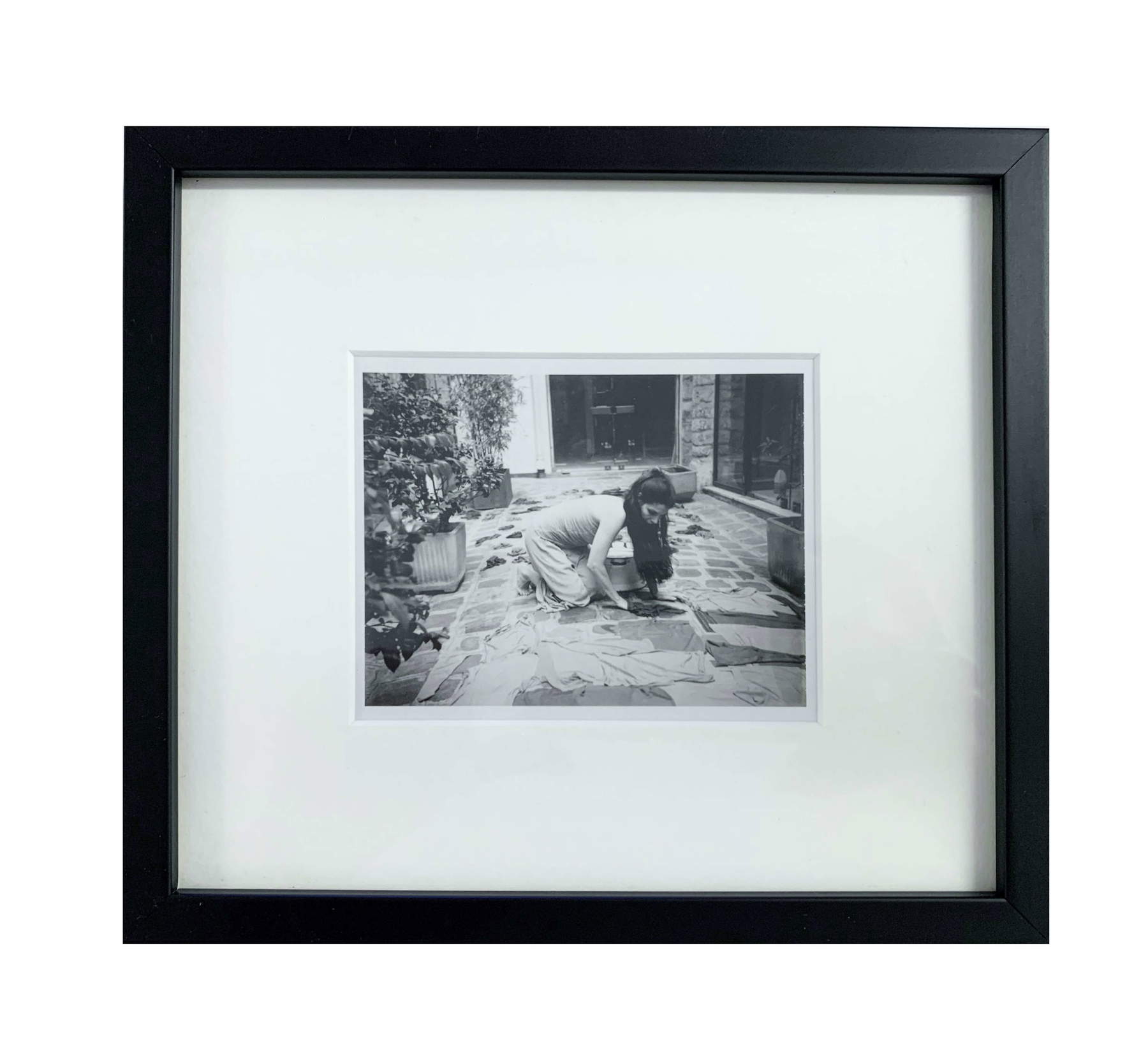

Casolaro is not the only Italian who has worked in and for Bosnia. Simona Barzaghi, born in Milan in 1960, and author of a long journey along the Drina, the river that divides Bosnia-Herzegovina from Serbia, did and does as well. For Barzaghi, who “is involved in participatory practices in Bosnia-Republika Srpska, with the aim of carrying out artistic-cultural and intercultural projects with museums, schools, associations, refugee camps and social groups in fragility” (we read in her biography), that river line that she traveled on a boat taking water samples in transparent jerry cans, actually unites many things: nature first of all, people and ideas. This experience of hers has been formalized into a giant map to be traveled with the eyes and the senses, following the lines and observing videos and photos that see the author committed to engaging locals in a shared, non-divisive project. Waterline ’s red-dominant 2024, with the coeval contribution of the shots taken by Claudio Cristini and printed in black and white in a richly evocative report, is a hymn to joy in a context, that of the exhibition, dominated by problematic images, terrible memories and gloomy predictions about the present time.

Fronting Barzaghi’s human and river geography are two large installations by the third Italian, 53-year-old Neapolitan Romina De Novellis. “An anthropologist and visual artist active in Paris since 2008,” De Novellis is present at the Slaughterhouse with a performance, performed on site and documented now by a video, titled Na Cl O (2015-25), the chemical formula of sodium hypochlorite, the active ingredient in bleach, which “recalls the modern desire to disinfect, whiten, erase all traces.” And the performer washed the floor with pieces of cloth in the colors of the flag of Bosnia. While in the video-installation Si tu m’aimes, protège-moi the Neapolitan anthropologist and former dancer appears engaged in covering the ears of a hen, after having similarly lined her own, according to the ancient popular belief that loud noises, such as gunshots or bangs, make one sterile. “A minimal, delicate, seemingly anachronistic gesture,” writes Benedetta Carpi De Resmini about De Novellis’ project. “But it is precisely in this ancestral tenderness that a radically political action manifests itself.”

In times of “smart” bombs, deadly missiles, and explosive drones, "protecting her fertility (of the hive, nda) thus becomes an act of care and survival, a way of resisting the normalization of violence," suggests the curator. De Novellis’ video, moreover, is placed inside an enclosure composed of hay bales, mimicking a farm, where a real fountain in action appears-and we are in front of the Drina of the Waterline installation. The water gushes not from just any sculpture but, as in the classical sarcophagi turned into fountains, from the structure where chickens are usually killed. Thus the quintessential symbol of life and regeneration takes shape and movement.

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.