Two exhibitions pay tribute to Mario Giacomelli on the centenary of his birth. In Milan, Mario Giacomelli. The Photographer and the Poet is staged at Palazzo Reale, promoted by the City of Milan - Culture and produced by Palazzo Reale and Archivio Mario Giacomelli, in collaboration with Rjma progetti culturali and Silvana Editoriale. In Rome, Mario Giacomelli. The Photographer and the Artist finds its home at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, promoted by the Department of Culture of Roma Capitale and Azienda Speciale Palaexpo, produced and organized by Azienda Speciale Palaexpo in collaboration with Archivio Giacomelli. Both exhibitions, curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and Katiuscia Biondi Giacomelli, complete a long journey undertaken by the Mario Giacomelli Archive to re-examine and explore works and materials in depth, in the awareness that constant work of protection and interpretation is necessary, conducted with philological rigor and critical passion.

Thus were born two exhibitions that offer visitors not only the original and vintage prints - an appreciable rarity in the contemporary photographic exhibition scene - but also unpublished materials such as writings, comparison specimens and testimonies that reveal the full originality of the photographer’s creative process. Two distinct narrative paths that together restore the complexity and interpretive richness of Giacomelli’s images. We can say that the photographer who stated, "Here from the moment the viewer observes the image, sees another, another and another and begins to wonder ’But what did he mean? What did this photographer mean?’ Here from that moment the dead image begins to breathe comes out of its muteness. At least that’s what I think’ (quotes are from the Rai program The Pomegranate. The Good Earth by Stefano Viaggio from 1994, which can be viewed on RaiPlay).

His relationship with poetry is explored in the Milan exhibition. It is perhaps the most obvious influence in Giacomelli’s images in which that same elevation toward lyricism and abstraction that make poetry a language that transcends patterns is visible.

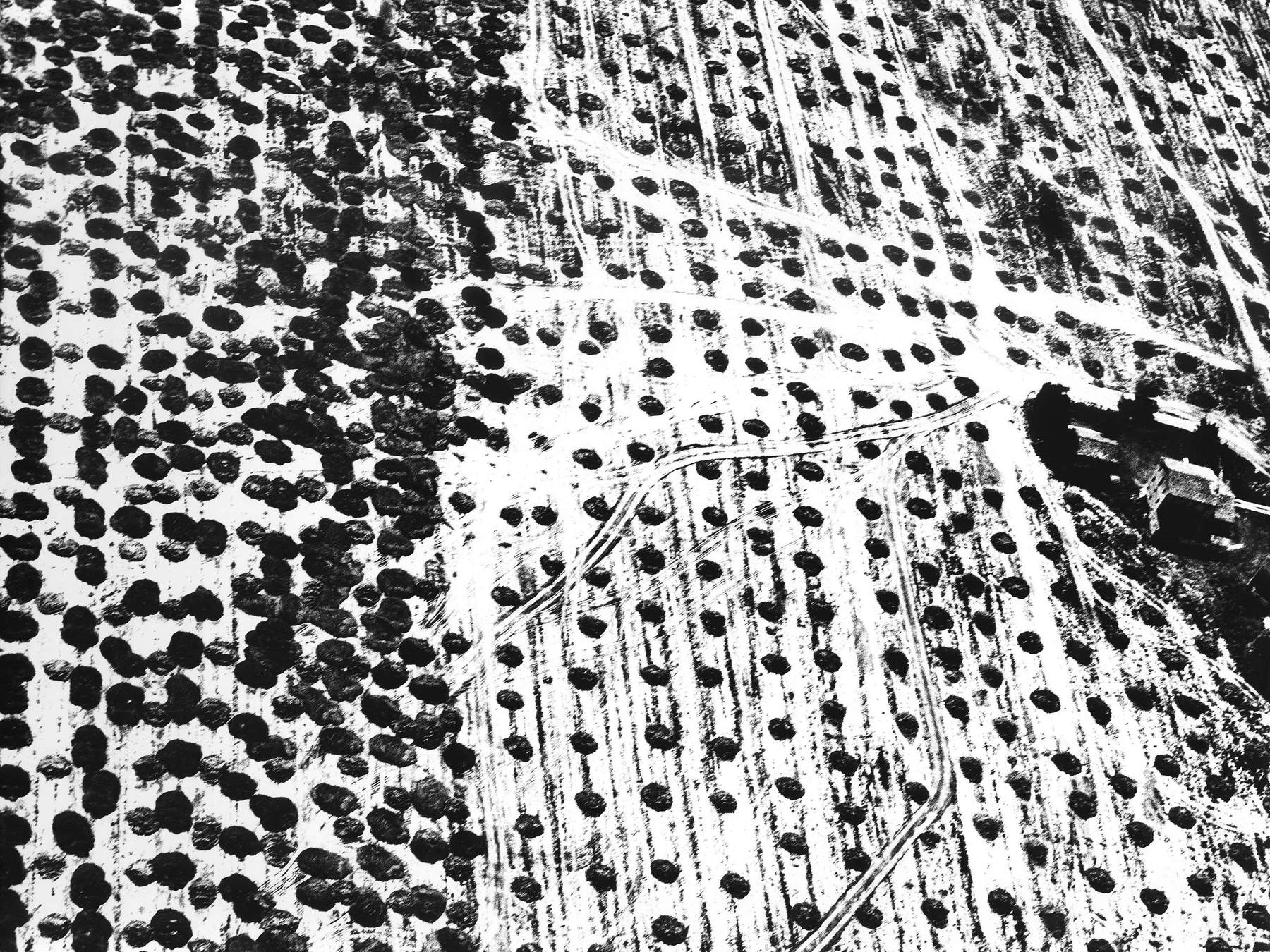

Even in the projects, the relationship is easily readable; the photographs are never a mere illustration of the text, as in the series Caroline Branson from Spoon River (1967-73), inspired by the text by Edgar Lee Masters, where Giacomelli stages the passion of two lovers that transforms the world around them and who, enraptured by love, merge with nature, losing themselves in it. Then, in the evolution of his artistic journey, the poetry gradually sublimates into the images, and becomes no longer just inspiration but an integral part of the language. Such as in the series L’infinito (1986 -1990), which stems from Giacomo Leopardi’s poem of the same name. The choice of a photographer can only fall on a poem that speaks of a gaze, a gaze that clashes against an element that limits it and pushes the imagination to expand towards a boundless space and time.

Mario Giacomelli is undoubtedly the Italian photographer who more than any other pushed research on photographic language into uncharted territories, relentlessly experimenting with the expressive possibilities of the medium. His work bears witness to a relentless investigation into the limits and potential of photography, taking technique to extremes and extending language. It was he who elevated Italian photography from the documentary to the artistic plane, creating a revolutionary visual code that opened up new avenues of expression and profoundly influenced the evolution of contemporary photography in our country.

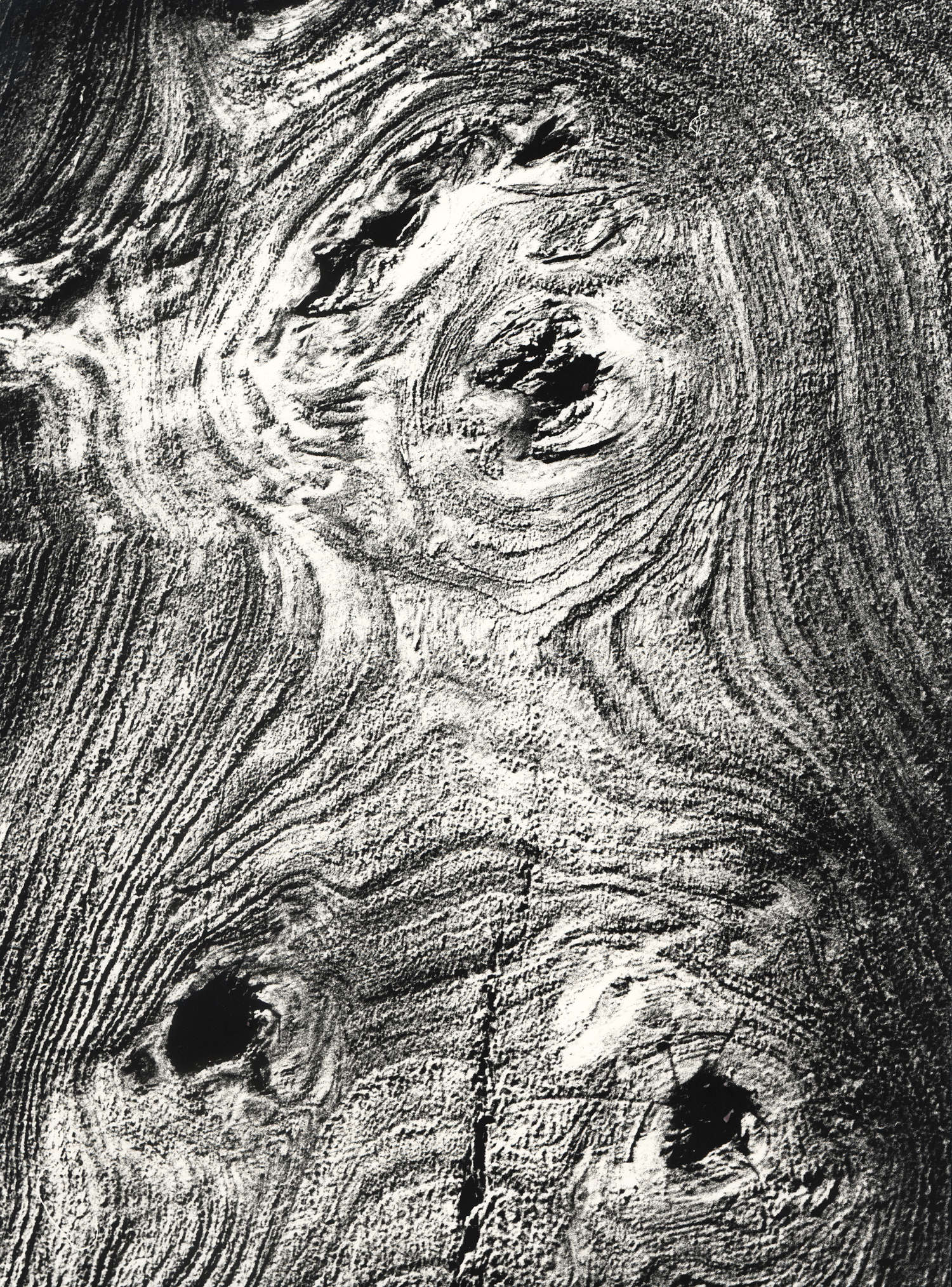

The Rome exhibition explores the relationship of Giacomelli’s works with those of contemporary art. Giacomelli’s admiration for Alberto Burri, shown in the exhibition alongside La buona terra (1964-1966), was well known. Here an affinity of research is evident: where Burri physically excavated the earth of his Cretti, Giacomelli excavates the black on the white of his photographs. He not only resumes, but extremes the contrast, to the point of reducing the scale of nuance to the minimum necessary. After all, this represents the highest point of Giacomelli’s research: black and white, in no uncertain terms. He, who has investigated photography in all possible directions at the end of the path arrives at the starting point: at blinding white, at the starkest black. Giacomelli is the end and the beginning. An origin that photography itself never really had, since even the earliest experiments, while extremely less defined than today’s technology, already allowed a variety of nuances to be reproduced and preserved. Thus Giacomelli’s work invents a linguistic principle, a first sign, a binary system from which ideally everything is born.

A black and white fully expressed in Io non ho mani che mi accarezzano il volto (1961-1963), named after a verse by David Maria Turoldo, and constituting Giacomelli’s most famous series, the one that made him world famous. A series that unites the two exhibitions.

Here the “pretini,” as these photographs are commonly known, depict students at the Bishop’s Seminary in Senigallia, where Giacomelli had gone inspired by Turoldo’s verses. They are verses that speak of loneliness, of detachment from the world’s emotions, just as in the collective imagination young seminarians do as they devote themselves to a life of dedication and prayer. However, after more than a year of setting and contact with their own, which was necessary to work out ideas and to accustom these young men to photographic shooting, Giacomelli had discovered a reality different from what he had imagined: in moments of recreation, the young priests played and experienced moments of leisure just like ordinary boys. “In the first pictures the image came out of the seedbed, of these priests you just think they are praying. And then little by little I almost felt some compassion for these people who were playing, but they were playing like children who would never grow up,” Giacomelli says.

These are joyful, festive photographs of them dancing, making a roundabout and playing ball. With his extreme and primitive black and white, of black figures on a white limbo with no reference of space, Giacomelli expresses the purest of emotions: the unconditional joy and serenity of seminarians far from the world playing, with the simplicity of those who have left worldly things behind. “I did not understand what the strength of these people was, whether there is something great or whether they really always remain children without the problems that men have in life.”

This is the only series not associated with another artist because it is itself conceived as an installation that restores the circularity represented by the images. A detail, this one, that will drive the collectors chasing the “pretenders” crazy in the auctions where Giacomelli is increasingly present. Who knows, maybe there will be an unobtainable pretino from the collection, a rare, a super rare, as in the best collections of figurines.

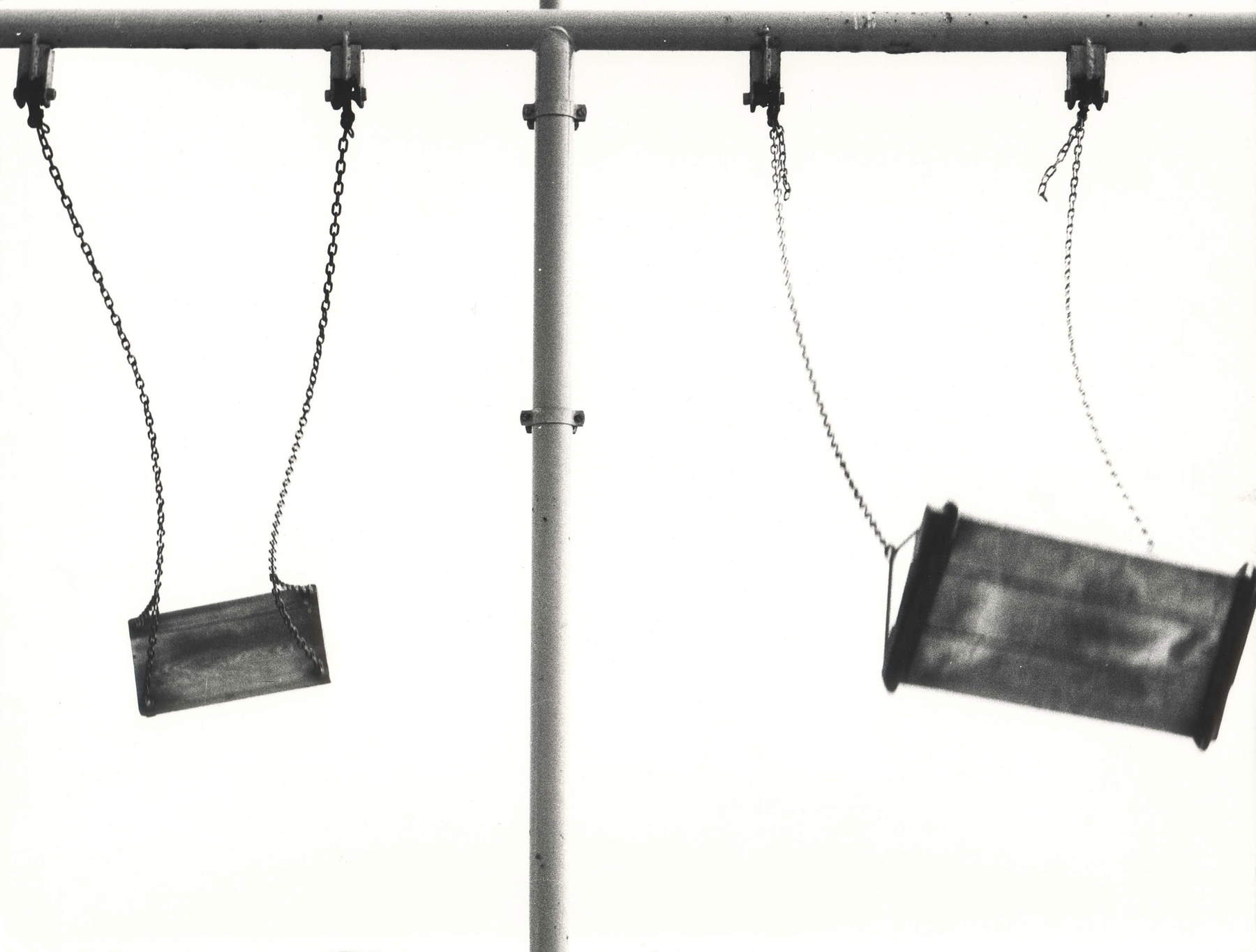

All the other series in the exhibition are compared with contemporary artists, including by associations after the works were made, the result of the curators’ reflection. And so Jannis Kounellis is placed side by side with the series Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi, E io ti vidi fanciulla, Lourdes, and Mattatoio, where a painful reality-illness, pain, popular piety, death-is the starting point. Although investigated by many Giacomelli certainly elevates language to where no contemporary has gone before. Thus, according to the curators, in Kounellis real matter is sublimated to a spiritual and symbolic dimension. Similarly, further on, the landscapes of Presa di coscienza sulla natura (Giacomelli’s famous series), Metamorphosis on Earth, and others are placed side by side with Burri’s work Tettoetto for a dialogue on the relationship between matter and dream, typical of many artistic pursuits.

One wonders whether these associations are accessible to a non-specialized audience. In fact, an element of greater understanding of the choice is missing: as is the case with Burri, with the other artists, a note would be needed to make comprehensible not so much the contemporary art-about whose comprehensibility irony abounds-as the association with Giacomelli’s works.

Is this an accessible exhibition? How magical that word is: it is not only what is translated into relief panels or audio-described that is accessible, because the limitations are often cultural and educational. And so is this exhibition accessible? Is it understandable to those who do not know who Kounellis is, to those who do not know him? Or does it perhaps teach them through simple, plain-language texts? Perhaps not, but it is also true that it is not required to be. Besides, as Giacomelli said, “I marvel at those people who have understood everything. You see today people who have understood everything about everything and are still so young. To me it seems like I’m not so young anymore and I haven’t understood anything.”

The author of this article: Silvia De Felice

Da venti anni si occupa di produzione di contenuti televisivi per Rai in ambito culturale e ha ideato Art Night, programma di documentari d'arte di Rai 5. L'arte e la cultura in tutte le sue forme la appassionano, ma tra le pagine di Finestre sull'Arte può confessare il suo debole per la fotografia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.