There is good news and bad news that prepares visitors for their itinerary through the halls of Titian and the Image of Women in Sixteenth-Century Venice, the exhibition that, through works of considerable relevance (not only by Titian: there is much more), aims to reconstruct the terms of the female presence in sixteenth-century Venetian society. The bad news is that the exhibition curated by Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and organized by Skira, the second stage of a project that began a few months ago at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and has now landed in Milan, at the Palazzo Reale, lacks a rather substantial number of paintings that supported the Austrian exhibition. Some are also weighty absences: it is not possible, for example, to witness the comparison between the Young Nude Woman in the Mirror, a masterpiece by Giovanni Bellini that in the Vienna exhibition dialogued with Titian’s Woman in the Mirror and whose comparison animates some of the most beautiful and intense pages of the catalog (a publication where the list of works and the division into sections follows the order of the Vienna exhibition and not that, in part different, of the Palazzo Reale review). Drastically reduced, then, is the section on “Venetian beauties,” which nonetheless preserves some first-rate works at the Royal Palace as well. And this is just to limit ourselves to some of the shortcomings.

There is good news, however. Meanwhile, even with all the curtailments, the exhibition at the Palazzo Reale still maintains its organicity: it certainly lacks some sharp points that would have extended the discourse (the comparison between Bellini and Titian mentioned above, for example, in Vienna held a section by itself, moreover not secondary and integrated with other works: to remedy this absence there is a reference to the catalog), but the overall image of the exhibition holds and the objectives of outlining “the image of women in sixteenth-century Venice,” as per the title, are nevertheless satisfied. What’s more, there are some interesting loans in Milan that were not there in Vienna: the best is undoubtedly the Portrait of a Little Girl from the Bedetti House, a masterpiece by Giovanni Battista Moroni granted by the Accademia Carrara of Bergamo, but not secondary in the overall economy of the exhibition (and, indeed, in this case we are on a higher level than in Vienna) are, among others, Palma il Vecchio’s Venus from a private collection and Tintoretto’s The Origin of Love, for the reasons discussed below.

In order to focus on the historical, social and cultural context of the exhibition, it may be useful to start from a point that is a few decades beyond the situation the review frames: it is 1642 and Arcangela Tarabotti, a Venetian, writer and religious despite herself (monkhood was the common fate of almost all young women from upper-middle class families who had no role in their fathers’ marriage policies: Renaissance society, as is well known, was strongly patriarchal) wrote The Paternal Tyranny, probably the strongest and certainly the most famous work of denunciation, published posthumously in 1654, against the custom of forcing girls to take vows against their will. And it is also perhaps the most powerful vindication of women’s dignity published at the time: it represents, scholar Eleonora Carinci has written, “the highest moment reached by women in the early modern age who expressed their thoughts with the pen.” it might not be far-fetched to imagine that Elena Cornaro Piscopia, a Paduan, the first woman graduate in history, a teenager when Tarabotti’s books were being published, had heard the strong echo of the “protofeminist” writers, as they have often been called, and that her family had vivid memories of the debate on the condition of women a few decades earlier had shaken intellectual circles in the Veneto and beyond. Indeed, it would be difficult to imagine Arcangela Tarabotti’s works without the literary and cultural background that in the sixteenth century animated the querelle des femmes, which was particularly felt in Venice, a city much freer than others of the time, a cultured city, a city where women (not all, of course) had wider margins of independence than their peers in other cities of Italy, and therefore a city that also experienced a conspicuous literary and intellectual production by women. Around 1600, Moderata Fonte’s Il merito delle donne (The Merit of Women ) and Lucrezia Marinelli’s Le nobiltà et eccellenze delle donne et i difetti e mancamenti de gli uomini (The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Faults and Lacks of Men ) were being printed, two other protofeminist writings that intervened in the discussion of gender relations at a time when reasoning about women meant not only addressing the issue of her status and her social and cultural constraints (one of the topics of the querelle, just by way of example, was women’s access to education), but it also meant questioning secular prejudices in order to reevaluate the position of women themselves. Perhaps the highest merit of the Italian-Austrian exhibition is precisely that of emphasizing these aspects, which hardly leave the circles of insiders, in an exhibition intended for the general public that for the first time deals with such important topics.

The highly intelligent introductory room offers a symbolic start to the exhibition’s topics by emphasizing the religious implications of the querelle des femmes: Titian’s Madonna and Child and Tintoretto’s The Temptation of Adam and Eve, by introducing the audience to the two most decisive female figures of the Christian religion, namely Mary and Eve, remind us how God’s pure and chaste parent and Adam’s companion, solely responsible for the expulsion from the Earthly Paradise according to misogynistic interpretations of the book of Genesis, had informed the idea of women in Christian society. The argument of Eve’s guilt, moreover, also animated the arguments of those who, in the querelle des femmes, maintained the most intransigent positions: to see Mary and Eve in the “premise” of the exhibition is therefore also to enter the everyday cultural debate of the time. We are talking, after all, about a review of pure social history of art, although the plan becomes a little more nuanced in the first section, devoted to portraiture, a kind of exhibition within an exhibition that allows for more sinks: on the social role of the female portrait, on the evolution of female portraiture in sixteenth-century Venice (a place where the portrait genre was less widespread than elsewhere, since the dissemination of one’s image to posterity long remained a concept far removed from the mentality of the Venetian patriciate), on the cross-references between ancient and modern (a couple of busts from the Roman era are also present).

The female portraits, Charles Hope explains in the catalog, were much more unusual than the male ones and “generally dedicated to women of the highest rank [...] although not infrequently princes or other powerful people commissioned artists to paint portraits of their mistresses.” In this sense, Titian and the Image of Woman offers examples of all cases: one ranges from the celebrated portrait of Isabella d’Este to that of Elisabetta Gonzaga della Rovere, both works by Titian, to effigies of women that are difficult to identify, partly because the purpose of Venetian portraiture was not necessarily truthfulness, but rather beauty understood as the representation of an ideal canon for which physical appearance mirrored a woman’s virtue and which, in the midst of Petrarch’s revival (think of Pietro Bembo’s Asolani, which are a product of the same cultural temperament), conformed to the paradigm of feminine charm codified by the Tuscan poet, and whose elements often responded to social and allegorical reasons. Illuminating in this regard is Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo’s fine essay on the “eloquence of hair.” Eleonora Gonzaga’s close-cropped hair is the counterbalance to the armor worn by her husband Francesco Maria Della Rovere in the pendant preserved in the Uffizi and conveys the image of a woman described by Pietro Aretino in one of his sonnets (which had Titian’s painting as its subject) as, Dal Pozzolo points out, “a monument of modesty, beauty and prudence” (“Honesty in her dress dwells, / Shame her breast and crin veils and honors her, / Love afflicts her lordly gaze”). One more aspect among many will be of interest to fashion enthusiasts: admiring the portraits of the women of the time, sometimes portrayed from an early age (the portrait of Moroni mentioned at the beginning thus stands out), also means considering these elements, which are far from unimportant.

Closely linked to the section on portraits is the next one, dedicated to “Venetian beauties,” which in Milan counts on three loans (this is the portion of the exhibition that has been most reduced with respect to the Viennese itinerary), to which are added the prints by Cesare Vecellio De gli habiti antichi et moderni: they are the Young Woman in a Blue Dress and the Young Woman in a Green Dress by Palma the Elder and the seventeenth-century copy of Palma’s Bella preserved at the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid (in Vienna it was possible to see it in comparison with the original). The term “belle” denotes a genre, the curator explains, of “half-figure paintings whose unifying characteristic was erotic beauty.” Abstract paintings of women, so to speak, and therefore a different genre than that of the portrait, as well as one formulated according to a precise code (the “belle,” for example, had to turn her eyes to the viewer or, in the case where her gaze did not cross that of the viewer, she still had to make a gesture that was even only veiledly inviting). Palma the Elder, with his florid, soft-skinned women, was long considered the inventor of the genre, as “beauties” abound in his production (today, precedence is thought to go to Titian). Around the “beauties” centers one of the exhibition’s pillars: the interpretation of their role. The exhibition, in essence, questions who the beauties were, read sometimes as novice brides, sometimes as courtesans, that is, women engaged in a form of meretriciousness typical of the time for which those who practiced this trade, in addition to having a high standard of living (their services were aimed at a wealthy clientele), were able to entertain, converse, recite, declaim verses and often write them (Veronica Franco, one of the greatest poets of the 16th century, was a courtesan and began the trade of prostitution at the age of 20). And portraiture was for them a form of promotion, of asserting their image. Who then were the beauties, Ferino-Pagden wonders? The idea to which the exhibition calls the public’s attention is that, at least in some cases, we can speak of brides-to-be or novices. This might be the case, the curator suggests, with the two young women by Palma the Elder, the one in blue who is looking sideways at the viewer (in other words, she is judging him, evaluating him, weighing him), and the one in green who, like the other, has a ring on her left ring finger and lifts the lid of a box filled with laces (the famous, or infamous, “love laces”). These are two works that have long been studied by critics: Philip Rylands, for example, believed them to be portraits of two courtesans, while for years Ferino-Pagden has insisted on their identification as young brides. Perhaps, as Andrea Bayer suggested in 2008, to be read in an idealized key, as transpositions in images of Petrarch’s language, as portraits of the beloved similar to portraits in verse, “where the hair is always golden, the eyes amber and ivory, the lips coral and the teeth like pearls, the cheeks like two roses, the forehead serene, the breasts white as snow.”

The breast of the beloved is another of the key aspects in decoding these paintings: this is demonstrated by the most precious of the masterpieces on display, Giorgione’s Laura, whose exposed nipple barely poking out of her fur has almost always been read as a kind of carnal invitation. It would be, on the contrary, a declaration of love, as if to say that the woman is opening her heart. Also contributing to this reading are the very recent studies by Silvia Gazzola, who in 2018 subjected a 1616 treatise,Giovanni Bonifacio’sArte de’ cenni (The Art of Nodding), until then half-known but which proved to be a fundamental guide for having a better grasp of gestures in paintings of the time, to a thorough critical investigation. In certain works, the display of the breast, Gazzola explains, “is to be considered as virtuous and delightful, since it is inserted in the framework of a matrimonial chastity. The final destination of the nod saves the latter from the moral stigma that would mark it if it were considered in absolute, that is, outside of a context.” And the context is given by the woman’s clothing, her adornments, her attitude. On this basis, therefore, it would be necessary to read, in addition to Laura, who stands alone on a wall (and who knows whether her fur coat is to be understood in its meaning as a gift that the husband gave to his wife, or in its status as a garment that women wore in intimacy before giving themselves to their men, as the sources of the time attest: the two hypotheses would not be mutually exclusive), also the other works arranged in the same room, namely Paris Bordon’s Portrait of a Woman in a Green Dress and Bernardino Licinio’s Woman Discovering Her Breasts on loan from a private collection. The latter is one of the new additions to the exhibition: the name of the author was discovered thanks to the restoration carried out in preparation for the exhibition, and it is also, the curator explains, a canvas “of extraordinary importance because of all it has the greatest claim to be an authentic portrait of a young woman, and thus to immortalize a precise woman.” Mammaries in the air also return, comforting this hypothesis, in the relatively new Young Woman with Her Betrothed, another painting by Bernardino Licinio (the hypothesis of identifying the two young people as future husband and wife is by Anouck Samyn and is proposed for this exhibition) that enlivens, along with four other paintings, the section devoted to couple portraits: scenes of passion, exchanges of promises, arranged marriages typical of the social practices of the time (as the gift of the gold chain in Paris Bordon’s The Venetian Lovers would suggest), distant couples compose a sampler of certain interest.

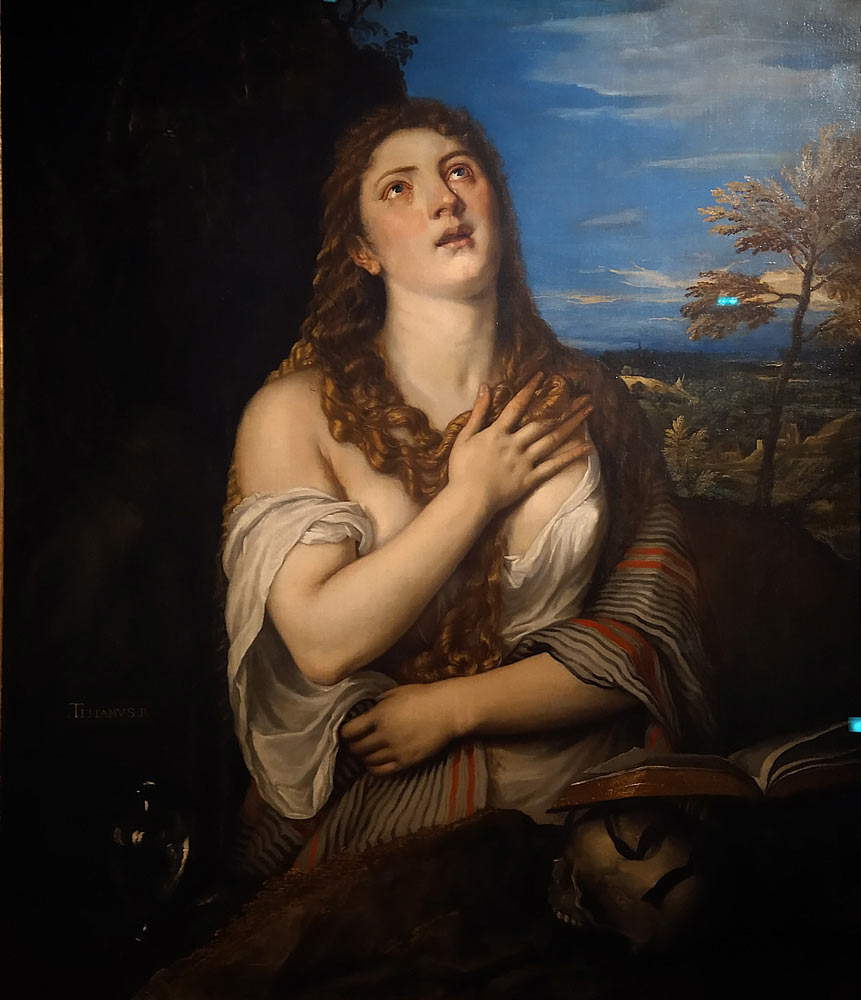

To make evident the qualities of women, central arguments in the querelle des femmes, the images of saints and heroines of antiquity, to whom a section is devoted, play an extremely significant role: they were the embodiment in images of the virtues that advocates of female dignity pointed to as arguments in their positions in defense of women. “Courage, self-sacrifice and determination combined with chastity, virtue and modesty characterize the personalities celebrated in so many representations,” writes Francesca Del Torre Scheuch: so here is the image of Titian’s Lucretia, a symbol of courage and marital fidelity that allows us to address even en passant the theme of violence against women (although the Cadore artist painted far more brutal works on the same subject). The Judith (Lorenzo Lotto’s from the BNL Collection and Paolo Veronese’s from the Kunsthistorisches Museum are on display) was an example not only of female courage, but also of women being able to perform actions considered typically masculine. And then again the Susanna of Tintoretto’s very famous painting, an example of violated innocence, purity, and trust in divine justice. The list also includes, of course, Mary Magdalene (although it should be noted that the space devoted to female spirituality is very small): on display is the famous image by Titian, whose archetype is the Penitent Magdalene from the Pitti Palace, and which comes to the Royal Palace with the version from the Stuttgart Staatsgalerie, where the saint appears clothed. This is the most conventional section of the exhibition: however, the discourse changes in the next two rooms, dedicated to literary productions (female and not: space is also devoted to the literati and intellectuals who intervened in the querelle des femmes).

Venice, the panels in the room remind us, was the European capital of publishing in the sixteenth century, and this condition allowed the development in the lagoon of a heated cultural debate that often expressed itself in the forms of dialogue, one of the most popular literary genres of the time, and a favorite for confronting two positions (and asserting one’s own, of course). The two sections gather not only portraits of literati of the time but also printed volumes and manuscripts. Some of them contribute to give the audience an idea of the cultural production of the time: the works of Pietro Aretino assume a certain relevance in this context, particularly the Ragionamento della Nanna e dell’Antonia, a dialogue between two harlots who, in decidedly colorful language, describe their situation (the work is considered one of the first examples of pornographic literature). We get to the heart of the querelle des femmes with Cornelius Agrippa’s treatise Della nobiltà et eccellenza delle donne, printed in Venice in 1549: curious to note that for the German philosopher, the expulsion from the Earthly Paradise was Adam’s fault and not Eve’s, since God had communicated to him the prohibition to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Ludovico Dolce’s Dialogo della institution delle donne (Dialogue on the Institution of Women ) also fits into the debate, from which we get an accurate picture of woman, not only as a mother who follows her children with loving care, who diligently administers the household and who is obliged to bear with humility all the hardships caused by her husband, but also as a person who “de’ learn letters, dannandosi la opinion de’ volgari,” who must know how to read (consider that, according to the statistics reported in the catalog in Anna Bellavitis’ essay, in the Venice of the 1680s 26 percent of males were schooled compared to only 0.2 percent of women), who must “pleasantly” resume her husband in the errors in which he has incurred. In this chapter of the exhibition there is also a great deal of emphasis on women’s literary production: Moderata Fonte, in particular, presses hard on the importance of receiving an education to enable women to have their own opinion and to be able to question what men claim, while The Nobility of Lucrezia Marinelli son been called by Margarete Zimmermann “an early form of female literary criticism” against the patriarchal system, which in the treatise is judged in all its faults also with certain tasty irony. Venice as a city of women, Venice as a place where feminism germinates: this is the idea the exhibition aims to spread.

It closes with three sections devoted to myth and allegory, aligning a sequence of masterpieces: Palma the Elder’s Nymphs at the Bath, the aforementioned Venus, also by Palma the Elder (compared with some splendid 16th-century bronzes and a prized Venus and Love by Giovanni Ambrogio Miseroni in chalcedony), Tintoretto’s Leda and the Swan, a version of Titian’s Venus and Love from a private collection, and the Kunsthistorisches’s Danae, executed by the Cadorean with the help of his workshop. Here we enter abundantly explored territories, included in the exhibition because of the fact that the various goddesses and nymphs of antiquity offered artists the pretext to depict women of great beauty but also to reason about love, about its risks and benefits. Interesting, then, is the presence of the two paintings that were not part of the Vienna itinerary: Bernardino Licinio’s Venus because it is the only example in the exhibition of a typically Venetian iconographic subject, that of the Venus or the nude, reclining nymph with which the Venetians had in fact invented a sexuality of images that urged the relative to also physically enjoy female beauty, as the generator of love and life. The presence of Tintoretto’sOrigin of Love, which is not in Vienna, is then closely related to Sperone Speroni’s Love Dialogue (the Paduan literary portrait, attributed to Titian, is in the exhibition), a work that was probably inspired to him by Tullia of Aragon (her portrait is also present): the painter takes up a motif from the Dialogue, and depicts Apollo accompanied by the earthly Venus and the heavenly Venus, the two souls of love according to Neoplatonic philosophy, caught holding a brazier lit by the sun that ignites the flame of love. Loving sentiment also ignites Titian’s mythological works that guide the visitor to the conclusion: the farewell is entrusted to the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s Nymph and Shepherd, a deliberately ambiguous and difficult-to-read painting. Titian, Thomas Dalla Costa speculates, was perhaps cultivating the intent “to visualize a feeling, to create with the brush a painted text,” seducing and engaging in a direct way the relative in order to convince him of the power of love.

Significantly, the exhibition catalog, a voluminous publication that is decidedly unconventional (it lacks worksheets, which are examined within a series of mini-essays that dissect the exhibition itinerary, almost like a thick guidebook: purists will probably not like the solution), closes with a tribute by Giovanna Nepi Scirè to Rona Goffen, a great scholar of Titian but also an art historian who conducted pioneering studies on Titian’s themes and the image of women, until now the only ones so extensive on the women of the Cadorian. It is therefore an exhibition that originated rather far back in time( Rona Goffen’s Titian’s Women is from 1997), so it should not be seen as insisting on particular commercial trends. Indubitable the contribution it will guarantee to gender studies, many the insights it offers to insiders and, even for a public not interested in these issues, an occasion of pure aesthetic enjoyment in front of a parade of masterpieces by Titian and associates. If we want, we could call it a necessary exhibition: it serves to unhinge many prejudices about the image of women in the sixteenth century, and thus to provide a much more articulate reading of the social and cultural role of women in the time, presenting their painted image dropped into a context that is delineated with great precision, always with references to the intertwining of art and the written word.

An exhibition, in essence, against simplifications and in favor of complexity and awareness. And an unprecedented exhibition, it must be reiterated: it is true that Rona Goffen has devoted extensive research to the subjects of Titian and the image of women, but these themes had never been the subject of an exhibition. Thus, an important first. And if it is true, as Sylvia Ferino-Pagden writes, that Titian recreated woman, the exhibition at the Palazzo Reale, one of the best that the Milanese venue has offered to the public in recent times though born elsewhere, has placed her at the center of attention in an original and innovative review.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.