Ettore Brezzo, originally from Giaveno (Turin) and graduated as an industrial expert, has always combined the concreteness of his work with a poetic sensibility and inexhaustible curiosity. His professional life has taken him several times to African construction sites, short stays that nonetheless rekindled a deep bond: that with Africa, rooted in a family affair. It was not only the landscapes that struck him, the wild expanses inhabited by majestic animals, but the cultural, ethnic and linguistic complexity, the traditions, the tribal tensions and, above all, the extraordinary richness of the human fabric.

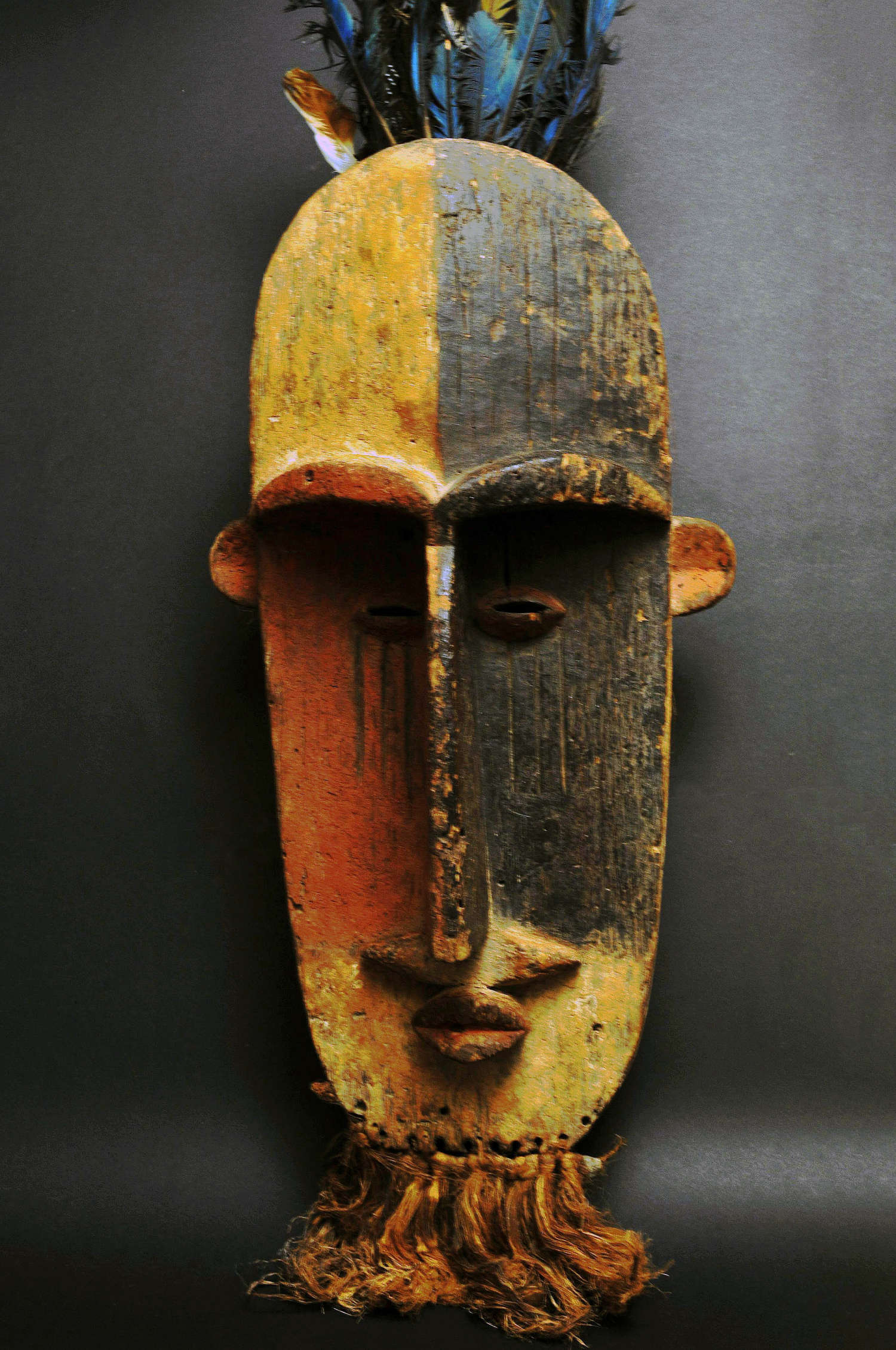

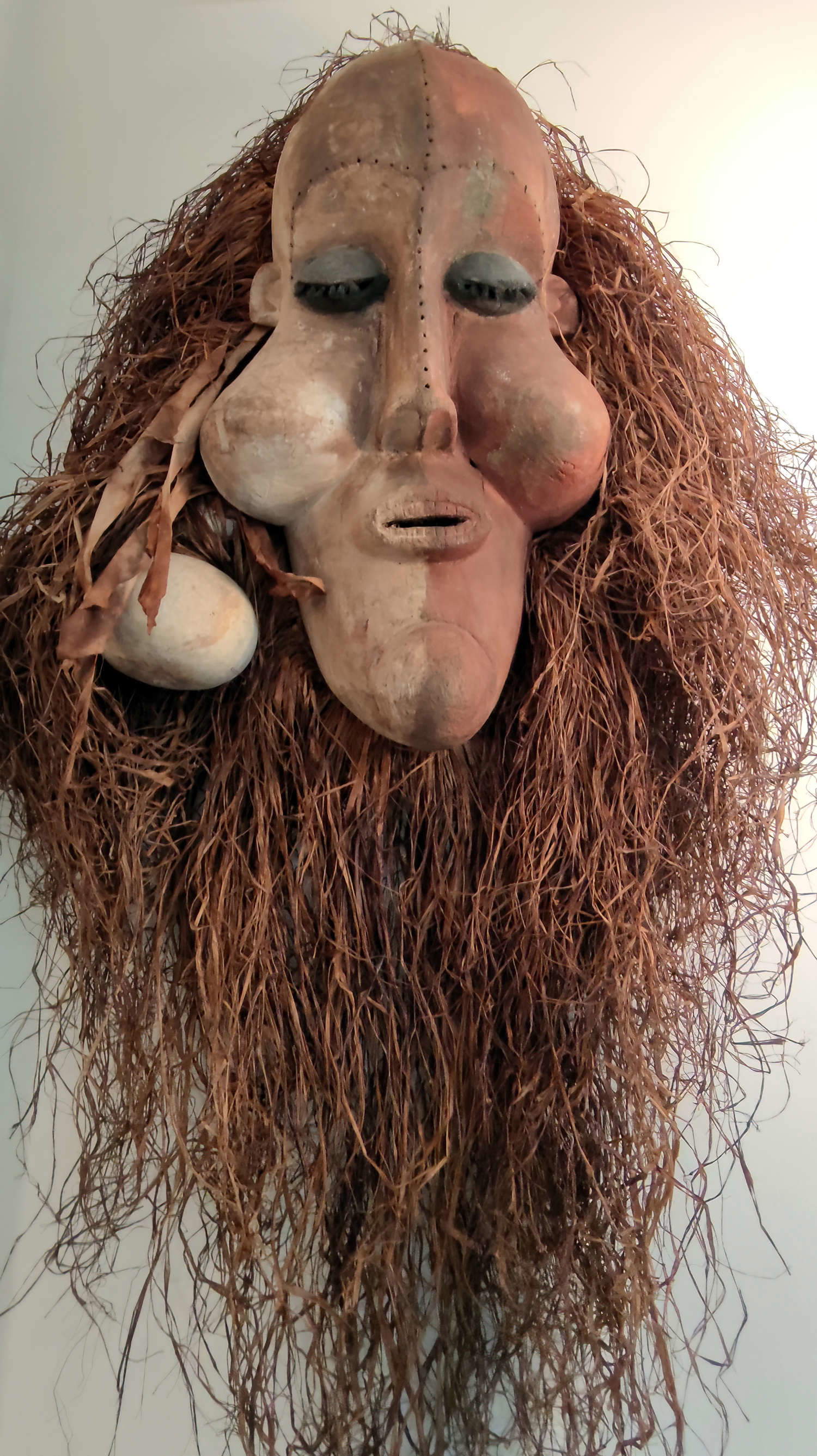

The experiences imprinted themselves on him to the point of becoming a constant presence, which he decided to bring with him to Val Sangone as well. A lifelong collector (minerals, stamps, fountain pens, postcards, antique tools, fossils), Ettore has developed a particular passion for African art. His intense and almost obsessive collection includes ritual masks, wooden sculptures, ceremonial objects, fetishes, and traditional tools, which today constitute a veritable home museum with over three hundred works, a living testimony to his dedication. Nostalgia for Africa became an integral part of his identity and prompted him and his wife to travel backpacking across the entire continent: more than 30 trips in 40 years, in search of an authentic Africa, without artifice, harsh and powerful, capable of leaving an indelible mark.

NC. What was the motivation that led you to collect works of African craftsmanship?

EB. In 1980 I got married and, for our honeymoon, with my wife Lina we chose an unusual destination: the North Cape. At that time it was still an adventure. Leaving from Turin by car, in almost two months we traveled 15,000 kilometers: Norway to the North Cape, then Finland, Sweden and finally Denmark, before returning to Italy. It was already a sign of a passion for travel that had driven us to explore Europe in easy ways, often by car or even hitchhiking. The following year we decided to change continents: the destination was Morocco. In those years traveling to Africa was considered dangerous, almost taboo, but we set out anyway. As in all our experiences, we avoided tourist circuits: we traveled with tent and backpack, sleeping in villages, sharing daily life with local people. Morocco does not belong to black Africa, it does not have the masks we would later learn about, but it offered us our first taste of that continent. We were struck by the hospitality, the humanity of the people and the landscapes, so different from Europe and capable of leaving a deep impression. In 1982 it was Egypt’s turn. We visited Cairo and the best-known sites, but we also chose less conventional routes, pushing on to the White Desert and the oases to Libya. In truth, the Arab dimension of the continent did not completely win us over, and we realized that our curiosity would take us deeper. So, the following year we embarked on a journey that would mark a turning point: Rwanda, Zaire, Central African Republic and Cameroon. In two months we crossed Africa from ocean to ocean. It was a momentous experience that made us fall permanently in love with the continent. Even before the masks or statues, it was the people, the landscapes, the endless trails and the emotions that enraptured us. We acquired our first African works almost by chance, as mementos to take back home, not yet as the fruit of ethnographic research. Bringing them with us was not easy: we traveled in local, often crammed vehicles, and transporting fragile objects was a feat. The actual passion matured slowly. At first the mask was a fascinating object, then came the realization: it belonged to a tribe, to a ritual, to a story. They were ritual tools used in weddings, in funeral ceremonies, in initiation rites. Each ethnic group had its own language and forms. From that point on, our travels became more and more research trips, discovering authentic masks and statues. Finding them was not easy then, and it is even less so today. In the markets of large cities, objects produced for tourism, recognizable to the trained eye, were circulating. Authentic works, those with museum value, had to be sought in villages, far from the commercial circuits. Yet, despite the difficulties, we managed to collect important pieces. Thus, the passion born almost by chance turned into a deep interest, able to accompany us for more than forty years.

What experiences you had during your travels in Africa influenced the way you perceived African works?

During our travels in Africa, we had the opportunity to observe some villages up close and come into close contact with the local people. Transportation is rare here, there are no buses or working railways, and people often travel in wagons carrying sacks of cassava along with people. Talking to those who live those areas on a daily basis allowed us to gather information that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. We thus understood that, despite the differences among the various tribes, there is a common thread: the initiation rites that accompany the children as they make the transition to adulthood. In each community, certain characters, belonging to secret societies, guide the youth through the rites. In reality, we know that their identity remains concealed. It is the mask that does the talking. This device creates a necessary detachment so that the young person does not recognize the educator (who could be an uncle or a family member) and instead perceives the mask as the bearer of authority and sacredness. We also had the opportunity to witness some initiation rituals and understand their profound function. The mask teaches rules of coexistence, tribal laws and moral standards, similar to the Ten Commandments of other cultures. It imparts knowledge about hunting, fishing, family life and sexuality and accompanies the boy every step of the way until he becomes an adult. In addition to the mask, initiation uses other ritual objects. Wooden statues and fetishes accompany young people along the forest paths, marking symbolic and spiritual stages of their journey. The mask itself can have multiple functions: guiding the dead, connecting the community with the forces of nature, enshrining rites of passage; it is never an isolated object.

In your opinion, could the deterioration of materials affect the value of the works you collect?

The most common African ritual objects are made of wood, a material widely used for masks and statues. Other materials, such as bronze, stone or clay, appear to a lesser extent. Wood, however, has a limited lifespan. Moisture, termites, and climatic conditions cause an object to reach a maximum of 100 years. Finding a mask or statue older than that is virtually impossible. In truth, deterioration does not diminish its value; rather, it provides an accurate indication of the object’s age. The cracks, holes, and breaks that form over time represent the object’s history and confirm its authenticity. In contrast, newer masks, such as those of the Yoruba used in the Gelede festival, show perfect surfaces and bright colors. Their beauty is an indication of the youthfulness of the object; value has nothing to do with it. Many ancient masks and fetishes are sold today because they are no longer part of the daily life of communities. In the past, the influence of colonialism and missionaries had led to the abandonment of some traditions, and even today young people tend to detach themselves from them, rejecting ties to practices they consider archaic and distant from their ancestors. Thus, what once had ritual value often becomes available for collectors. At the same time, some rituals and traditions are coming back to life, as they do in other cultures. I would call it a return to historical memory and ancestral customs, similar to the rediscovery of roots in the mountains or the appreciation of old homes and local traditions.

In your opinion, is it possible to observe a change in traditional materials in contemporary African crafts?

African ritual objects largely maintain traditional standards, both in conformation and material. Yoruba masks, for example, are immediately recognizable by experts. Even among a hundred different masks, the Yoruba one undoubtedly stands out. Each ethnic group follows specific patterns in construction, involving shapes, proportions, and materials. Today the tourist market may alter these canons slightly. Some objects, for example, once made of rarer materials, are being produced in more readily available substitutes. Today Benin Empire heads, originally made of bronze, may appear in clay or ceramic, while still respecting the aesthetic tradition. Some materials, however, such as stone, have never been used for masks, while wood always remains predominant because it allows for lightness and manageability: an ebony mask, for example, would be too heavy to wear, especially if decorated with additional objects and other elements. Tourism can therefore introduce some variations. In markets, for example, masks and figurines are often found in dark woods such as ebony, which was not actually traditionally used for masks. Despite this, the original material, wood, continues to retain the essential characteristics of the object. The tradition thus remains surprisingly constant, with modern variations not affecting the cultural value of the works.

To this day, is the production of African handicrafts influenced by technology, or do traditional techniques still prevail?

It may happen that today ritual objects, while maintaining traditional forms, are made with the help of modern tools. Work that once required manual hammer and chisel may now be facilitated by electric chisels or mechanized tools for circular parts. The tools themselves have also changed. They used to be forged in villages by the blacksmith, a figure of great authority and respect next to the village chief or feticheur. Today many blades and tools are bought in markets or come from abroad, for example from China, and allow for faster and more efficient work. This does not alter the value of the object. Just as in our industry, where modern machinery has changed production processes, the use of technology has sometimes improved the end result. For a long time African masks were considered simply handicrafts, until the early twentieth century. The interest of artists such as Picasso and Modigliani undoubtedly contributed to the recognition of their artistic value, shaping the perception of the works: from handcrafted objects to true works of art. Even today, even with modern techniques, masks remain an expression of creativity, aesthetics, and culture, and should not be seen only as handicrafts. It is authentic art.

In your opinion, did African idols and masks undergo a form of cultural colonization over time?

African fetishes represent one of the most obvious examples of cultural syncretism. As early as 1485, when the Portuguese reached the Congo coast, they had their first contact with the Congo Empire, a structured social organization with villages, roads, houses, a king and his subjects. The Portuguese, accustomed until then only to North Africa, were struck by the complexity of the society and the verdant Africa they found before them, so different from the imagined desert. With the arrival of the missionaries, the spread of Christianity began, initially reserved for the king and his close associates. Only later was the religion extended to the population, generating the first contrasts: how to accept a new faith without abandoning millennia-old traditions? This gave rise to syncretism, visible in ritual objects. A prime example are the congo fetishes, spiked and with a glass in the center that protects bilobo, a magical substance. The congo fetish actually echoes the Christian monstrance. The central glass recalls the host, while the nails symbolize the rays of power radiating from the center. The mirror protects the object from the evil eye, reflecting bad intentions. Each nail has a specific ritual purpose: to strike an enemy, gain protection or favor. Statuettes dedicated to motherhood also show similar influences. Among the Pende of Zaire, early statues represented the wife of the village chief. In time, influenced by Christian images, many took on the figure of the woman with a child in her arms, symbolically recalling madonnas. Similarly, in Cameroon Namji dolls were carried on the backs of girls to ensure healthy children in the future. African statuary, then, had practical, spiritual, and social functions, and evolved with history and outside influences. Finally, the role of sculptors should be emphasized. Each individual master added his or her own imprint while respecting the traditional patterns of the tribe. Thus, even within a strict tribal canon, each mask or statue acquired refined details.

In 2025, do African fetishes, ritual objects and masks retain a ritual role or are they produced mainly as souvenirs for tourists?

Traditional African art cannot be valued only by its price or rarity. Fetishes and masks, as well as figurines, are the expression of cultures thousands of years old, linked to rituals, initiations, and spiritual beliefs. Some ritual objects, such as those of the Songye in Congo or the more complex fetishes of the Congo, are almost impossible for tourists to replicate. Often, what is sold in tourist stalls is sloppy sculpture with no real connection to the canons of individual ethnic groups, created for mass consumption. Elongated masks with almond-shaped eyes or warriors with spears (which do not belong to any specific tradition) constitute the sculpture of mass tourism. They are beautiful to look at, but devoid of ritual meaning. In parallel, there is a restricted market dedicated to connoisseurs. Here the objects strictly adhere to tribal standards, are artificially aged and cared for down to the smallest detail: masks and fetishes that appear ancient may actually be only a few decades old, but their aesthetic and artistic value is immense. The actual age of the object does not always determine its beauty; what matters is respect for tradition, symbolic power and visual impact.vHistorically, some objects have been preserved through colonial intervention. Missionaries and collectors rescued masks and figurines that would otherwise have been destroyed during tribal wars or predecessor elimination rituals. In some cases, colonialists purchased the objects at token prices, ensuring that they would survive. Today, African nations such as Congo, Nigeria and other states claim their works preserved in Western museums, such as the Benin bronzes at the British Museum, or organize symbolic restitutions of rare masks, such as the Suku masks. Traditional African art is judged by what it represents, by its ability to convey stories, spirituality and culture, rather than by who created it or when. The sculptor, often anonymous, matters less than the object itself and its role in society: it is the idea, function, and aesthetics that give value to the work. The difference between tourist and traditional sculpture therefore is stark: the former is created for immediate and decorative consumption, the latter is a living work, part of a complex cultural and spiritual system, with well-defined rules and symbols.

Does niche tourism and the creation of African works tend to be concentrated outside the better-known tourist circuits or within them?

Today it is increasingly difficult to find authentic and valuable African objects, because over time local collections have become progressively emptier. As is the case in the European tradition of antique furniture, with the passage of generations and the advent of modernity, many valuable objects have been lost, sold or forgotten, and this has reduced the supply. In Africa, over the years, some works have been centralized in large villages or towns, where local collectors, often elderly and experienced, carefully guard them, selecting who can access them. Reaching the warehouses is complex: there are no signs or announcements, and only those who demonstrate knowledge and appreciation of the object can be introduced. Rare and extraordinary pieces are found here, collected from villages and passed down from generation to generation. To obtain a Fon altar, a complex fetish, or a statuette of great aesthetic value often requires dealing for days and demonstrating respect and expertise. The objects do not appear in tourist markets or galleries; their authenticity makes them expensive and hard to find. In contrast, mass tourism favors decorative or simplified objects: quickly produced masks, figurines, and bracelets with no real connection to tribal traditions. Those who buy them are looking for shape or color, not history or ritual function. Such objects, while beautiful to look at, do not convey the cultural identity of the ethnic group or the complexity of their original use. The experienced collector, on the other hand, seeks authenticity, adherence to traditional canons, and respect for original functions. The high price reflects not only rarity, but also the care, history and uniqueness of the work. In this sense, African art should not be valued only by age or pedigree. A well-crafted piece can be exciting even if it is recent, while an object that is old but lacks artistic value loses meaning.

How many works have you brought home from your trips to Africa?

Currently the collection has about 300 pieces, encompassing everything from large statues and masks to smaller objects such as bracelets. About 50-60% of the objects were purchased directly in Africa, with the rest coming from European collections or markets. Some pieces I have mentioned before, but overall the collection reflects a mix of artifacts acquired in the field and objects collected in Europe, always with attention to quality and authenticity.

In your opinion, how strong and ingrained do African art and craft traditions remain in new generations?

The new generations in large African capitals know little about their nation’s history and traditions. I have met young Italians or Zaireans who, upon seeing my fetishes, admitted that they did not even know that such objects existed in their country. This does not mean that culture is disappearing: many nations are rediscovering their roots through museums, as in Gabon, where Bieri ceremonies and ritual objects have been recovered and enhanced. In remote villages, traditions are much more alive: ritual and votive objects are still preserved and used in ceremonies, as is the case in small Italian villages with local museums dedicated to peasant culture. Here the link with tradition is direct, concrete and everyday. In capital cities, on the other hand, cultural revival is often linked to tourism and business rather than spontaneous knowledge of traditions. The market for African traditional objects follows two main paths: some original pieces, at least thirty to forty years old, circulate in local markets or collectors’ warehouses, while many new items or items made for tourism find their way directly to Europe. The price in Africa, even for authentic pieces, can be negotiated, while in European galleries the price is fixed and often higher. It should be emphasized that African ethnic groups never perfectly coincide with the national boundaries imposed by colonialism. Therefore, an object belonging to a certain ethnic group may be found in a country other than its origin. In addition, trade between countries makes it common for items to be moved between neighboring nations, as is also the case with European products.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.