What is art? Blessed Tolstoy who had the ready and certain answer: that which comes from the people. I, on the other hand, while working for two or three decades as an art critic, find myself like Augustine about time. If no one asks him, he knows, what time is; but when someone asks him, he cannot explain it. So he tried to define it by the intersection of past-present-future, and time is none of the three but it is a present-past, a present-future and, of course, there is also the present-present. These reflections were recovered by a philosopher of our contemporary, Henri Bergson, one of the modern thinkers who is very useful to read even today. But what about art?

The twentieth century is often considered the century of anguish. In fact, it has been defined in so many ways (and that says how nebulous our knowledge of it still is in retrospect); we usually think of the twentieth century as the century of carnage, of violence-which in itself is very true. So “creative despair” (a definition dear to Goffredo Fofi) would be that which pushes us to create despite the fact that everything around us leads us in the opposite direction, toward nihilism. Kafka (who has been taken as a foundation by many existentialist thinkers) says in a letter that he was actually having a great deal of fun when he was creating his hallucinatory stories, because the true artist, while creating, perhaps suffering, is always having fun. Milan Kundera, in The Art of the Novel, also addresses this apparent contradiction (by linking Kafka’s comedy to Fellini’s). The artist who does not take pleasure in creating, even when suffering or disgusted with the world, will never be a true artist. Art, in any case, even when it destroys does so from a positive perspective: Picasso painted Guernica and apparently destroyed, and someone caught in that work the quintessence of the demonic; but it is not an existentialism where all cows are black. Picasso certainly had fun when he was creating, he was not bored or even crucified: he put into each work an overabundant vitality, an eros that was never vanquished, all the more so in his late life, late sixties-early seventies, shortly before his death, when he painted pictures of an expressionism that puts to shame those of the German neo-selves of the late twentieth century, who certainly took that into account.

Folk art. Folk art is a concept I don’t like. Because I don’t like to put adjectives to things that have value in themselves. Art is art: there is no such thing as popular art, there is no such thing as bourgeois art, there is not even Catholic art. Usually these adjectives end up limiting what we are looking at. “This is a beautiful painting of bourgeois art” means nothing, just as it means nothing aesthetically to say that “this is popular art” (on the sociological level it might even make sense, but I am less interested here).

Tolstoy experiences all the typical issues of his era, but which are also those of the last European postwar period (much less clear today): for example, the guilt complex of intellectuals, who are often of bourgeois extraction, toward the last social classes is almost a commonplace. This problem existed in Tolstoy as well, as it continued to exist in European, and particularly Italian, art after World War II, culminating in the hermetic art of Duchamp and in the committed art at the front, in the 1970s, which revived social protests and ended in the fall of revolutionary hopes, the reflux into the private sphere and the conatus of terrorism. The idea in Beuys (and earlier, albeit with quite different assumptions, in Duchamp) that in every man there is or can be an artist, is a betrayal on both fronts: that of art and that of the man who suddenly believes that to be creative means to make something that comes from his own hands. Art is a serious thing not because it follows academic paths where one must have passed all the canonical degrees of a school education to express oneself, but because it is a mysterious reality where, without programming it, intuition, talent and vision merge into something that bears original and unique witness to one’s time. Those who painted the prehistoric cave graffiti (men or women) had not attended any Beaux-Arts academy, but the impulse that drove them to leave those marks on the cave walls, which have come down to us ten or twenty thousand years after they were traced, spontaneously expressed the same law that I tried to summarize earlier in three words: intuition, talent and vision. The gaze of one who translates experience into an analog language capable of saying everything without debasing it in the primacy of beautiful form. Art was born from this, and along time it has continually grafted onto itself (Degas argued that art is born from art, it is the result of conventions, and that is why he was skeptical about plein-air), but its own foundation of memory and culture has not changed its substance, which is that of giving voice in images to something that could not yet be handed down by word, oral or written.

Today, however, that guilt complex of children of the bourgeoisie toward those of the classes at the bottom of the social ladder has been largely lost, because talking about classes is lost in the tendency to betray all the ideals that the large and multiple middle class imprints on any consciousness that tries to remain free of buzzwords, the real limit (through political correctness) of the crisis in which our culture finds itself. There are no intellectuals on the horizon who are capable of tackling the edges of this wound with a fresh look, partly because those who interact with the world are generally privileged compared to the condition of the majority of ordinary people. If there are intellectuals who still feel this sense of guilt, it must be said that they have chosen to remain in the shadows, in anonymity, or to lock themselves up in their intellectual activities, perhaps because they think that all is lost and there is no solution to today’s injustices. And it must also be said that those who try to react to the state of things are often silenced by the engulfing “monster” that is the communication system. Those who go on stage, usually and all the more so if they express polemical opinions, accept the workings of the media machine, the cultural industry criticized by the writings of the Frankfurt School (from Adorno to Fromm, from Horkheimer to Marcuse, to Baudrillard).

If there is no longer the bourgeois intellectual who feels the same remorse that prompted some of our writers and artists to become the voice of this social dissent, it must also be said that many ethical parameters that once gave the world a dignity at least in facade, beginning with the profound transformation of the cognition of kitsch, which has become an endemic presence in our culture evolving with respect to the artistic dimension itself and transcending moral judgment by becoming precisely a kind of language of post-democracies: for this reason, too, we can no longer speak of social classes, since there probably exists an acculturated but agnostic upper-class plebs whose only religion seems to be consumption; and on the ’on the other hand, there continues to exist the disaggregated poor where everyone struggles with individualistic, almost blind instincts, that blindness of despair and bloodshed that is vented in the continuous festivals of indignation that dismantle the true power of what Testori called the insurrectional force of the “peripheries.” Of course it is increasingly difficult to say today whether the people exist and what they are. These categories no longer work because the concept of the homeland and the sense of the flag are no longer part of the common consciousness, and so even religion tends to become an expression of magical and superstitious valences, injecting poison and producing violence instead of cementing a new, more just and united society.

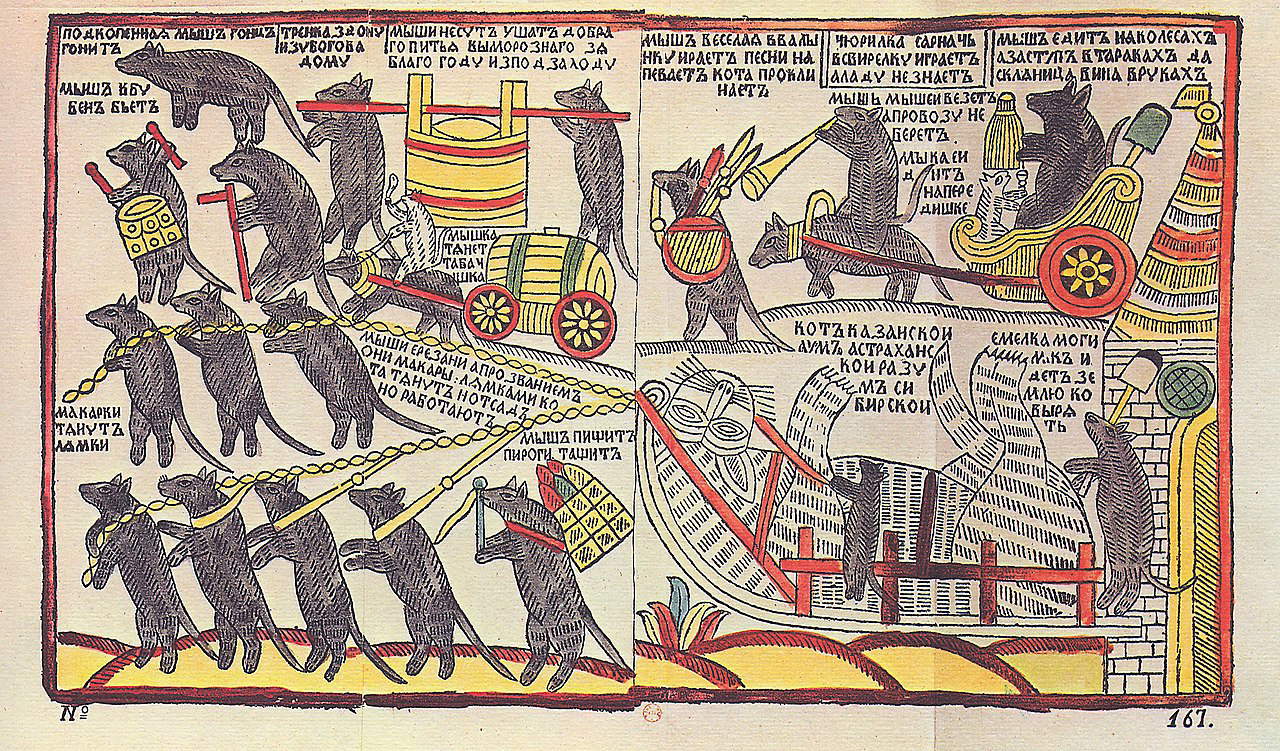

When he talks about folk art, Tolstoy actually carries within him a history of ancient Russian culture. I don’t know how many people today know the history of Russian folk prints: in the late seventeenth and very early twentieth centuries the art of lubok was widespread in Russia. These were folk prints that recovered ancient Russian myths, romantic and fable stories, mythologies, forms and iconographic memories that had been passed down from generations, a visual form of ethnology and anthropology, through highly ironic and very funny themes, as is the case of the cat’s funeral made by mice, which echoes the model of the hunter’s funeral made by animals, popular in the West. The lubki were often made by large European printers, through engravings, woodcuts, lithographs, and printed in hundreds or thousands of copies; they were then brought to Russia by the Colporteurs, the peddlers of prints and books. In the 19th century, color printing techniques, chromolithographs, became more widespread, but in many cases these sheets were still printed only in black and then placed in the hands of Russian peasant and housewives who, with the help of their children, painted them. They did it as they could because they had no artistic training, although by dint of coloring they had become more casual. Today, one is fascinated by the poetic beauty of these sheets; the fact that the colors come out of the margins of the drawing or even look almost like haphazardly applied glazes, which do not exactly match the image, gives these sheets an almost abstract value, which also inspired artists such as Andy Warhol (who had family origins in Eastern Europe).

Was this art popular? Yes, if by that adjective we mean a form that speaks to the common man about the history of a culture and society; those prints were produced by and for people from the humblest social strata (when we talk about folk traditions, we say this). The lubki had the function of a poster aimed at the people, reminding Russians of stories and traditions; their shelf life could be as short as that of a newspaper; many of these sheets ended up being used as wrapping paper for meat and fish in the markets, which is why, despite the large number of copies, few remain today). The tone of the stories and legends that were depicted on the lubkis had a distinct humor: it was in fact also an ironic form of countervailing power, and the great Russian writer and critic Mikhail Bachtin highlighted a century ago how laughter was the weapon with which the lower classes criticized the injustices of power.

So I think the art for the people that Tolstoy talks about is closely linked to the culture and memory of the lubki. But if we go through the history of art of the last two centuries in a quick review, we certainly cannot say that it is an expression of the people understood in this way, or even that it had as its intention to address the people (despite the old Catholic idea of images as Biblia pauperum). Art, even when it comes from the suburbs, remains an elitist phenomenon that appeals according to the logic of communication to the masses. But we certainly cannot say that the great revolutionary canvases of David, the director of the scene imposed since 1789, or even a painting like Delacroix’s Liberty Leads the People, while addressing the Parisian crowds, are a true expression of popular art.

The artist is always privileged, a loner, even when he is not born into a bourgeois background: if he ends up being an artist and becomes famous, he surely got there because he has a talent, but also because personal and social conditions allowed him to do so. Even in the past, there was still a hiatus between artists and the people: patronage was the subject that determined this “separation.” If we want to refer to an example dear to Testori, that of the Sacri Monti, we certainly have before us a case of art produced for popular devotion, through a figurative language suited to “Renzo Tramaglino and Lucia Mondella” before and after the Tridentine dictates; but those who were its creators generally enjoyed a good social position: Foppa, Gaudenzio Ferrari, Romanino were artists of good or even excellent economic condition (with bank accounts, so to speak). And for a time, even Caravaggio himself had a nest egg, later squandered. Perhaps we need to start from this fact also in order to understand the very sense with which in our postwar period the theme of the “human and non-humanist” artist was revived, which held up Caravaggesque interpretation itself for fifty years.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.