“Art must disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed,” stated CésarCruz. But what happens when it is preciselyart that is inconvenient to those in cultural or political power? And when awork is removed, erased, obscured, can we still speak of freedom of expression in the contemporary art world? The recent case of Lebanese-Australian artist Khaled Sabsabi at the Venice Biennale compels us to question these crucial issues.

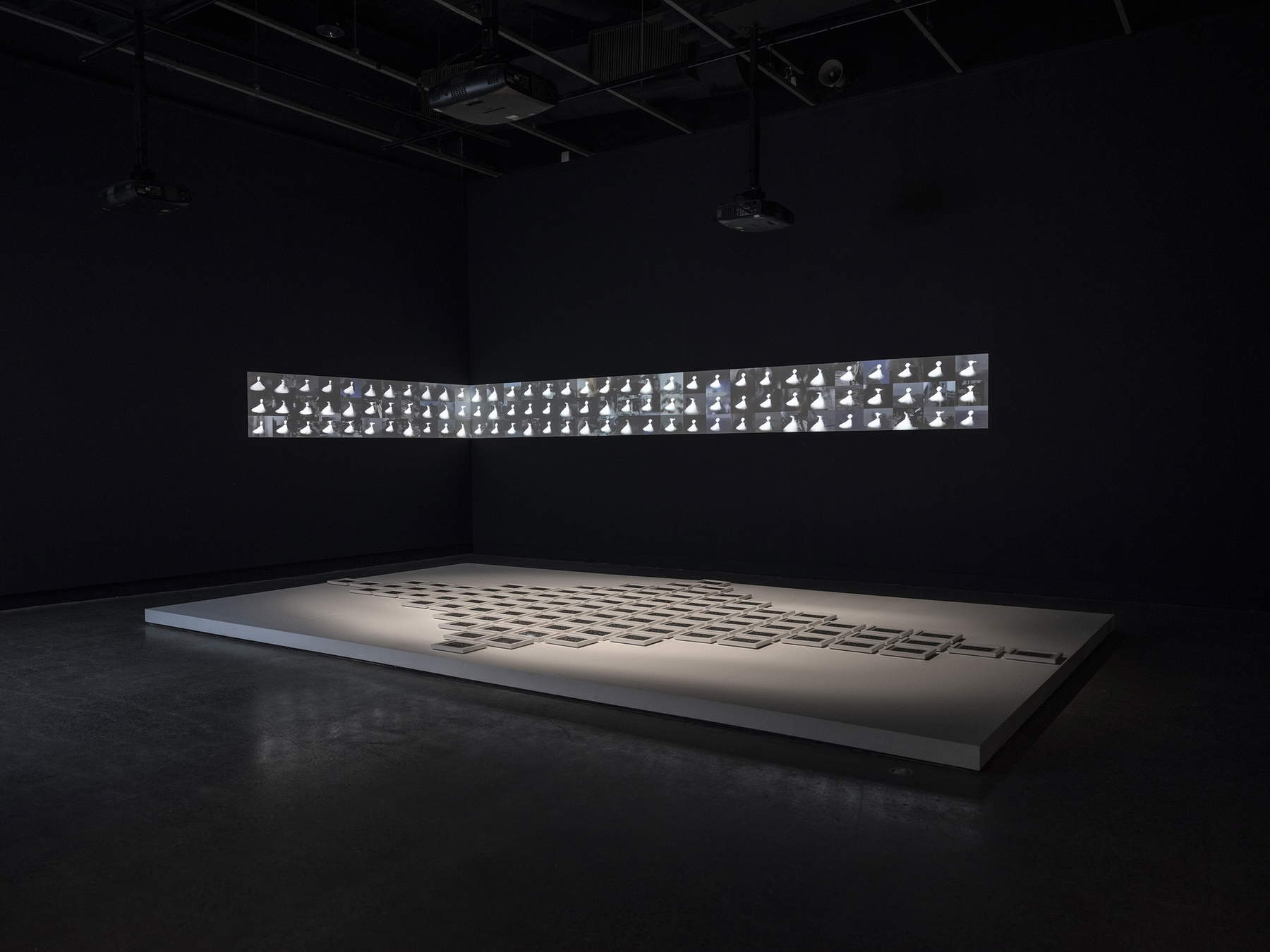

Sabsabi, known for his poetic and meditative work exploring diasporic identity, collective memory and spirituality in contexts of conflict, was to exhibit a video installation in theAustralia Pavilion at the 2026 edition of the Venice Biennale. The work, titled 99 Names, was an immersion in the mystical dimension ofIslam, centered on the ninety-nine names of God in Sufi tradition, accompanied by footage of community rituals in war-scarred places. But within days of the official announcement, the work was withdrawn by the curator, officially for “logistical reasons,” unofficially due to pressures related to its “political sensitivity” in an already tense international context.

The removal of Sabsabi’s work raised an echo of controversy in the art world, so much so that eventually Creative Australia, the public body that manages Australia’s presence at the Biennale, decided to readmit Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino after an “independent review.” Some critics spoke openly of censorship, of an unacceptable capitulation in the face of fear of offending political or religious sensibilities. Others pointed instead to the current global context, in which art that touches on religious or geopolitical issues is easily exploited or misinterpreted.

But the question, regardless of even the subsequent readmission of Sabsabi’s project, is broader and deeper: what is the role ofcontemporary artwithin cultural institutions today? Should it necessarily pose as a space of rupture, even at the cost of being provocative? Or should it assume the more accommodating role of “cultural ambassador,” avoiding the risk of conflict?

In the case of 99 Names, the question becomes more complicated. The work is neither a gesture of political denunciation nor a religious provocation, but rather an invitation to contemplation. Sabsabi, a convert to Islam who grew up between Beirut and Sydney, offers a visual language that seeks to bring together, not divide. Does the fact that this very type of work is perceived as “problematic” indicate a growing fragility of the art system, more concerned with acceptability than substance?

Biennials, from Venice to Berlin, from Gwangju to São Paulo, present themselves as spaces of radical freedom, places where the boldest voices, the most restless visions, the least heard narratives are celebrated. But how real is this freedom? And how much, instead, is it conditioned by power dynamics, geopolitical logics, a cultural industry increasingly linked to international diplomacy? Sabsabi, an artist who has made intercultural mediation the hallmark of his work, has thus found himself the victim of a paradox: his work is “too spiritual” for an art scene that tolerates Islam only if it is ironic or transgressive, and “too political” for a diplomacy that fears any reference to the Middle East. But can there still be art capable of escaping these strictures?

This is not just the Sabsabi case. In recent years, more and more artists have found themselves in similar situations: works withdrawn, texts changed, performances suspended. The language of censorship becomes subtle, mimetic, often hidden behind bureaucratic or seemingly “neutral” motives. But the result is the same: an artistic field that shrinks, that fears dissent, that sweetens complexity. In this scenario, the public, we the viewers, readers, citizens, have a non-secondary responsibility. Are we willing to confront works that challenge our certainties? Are we able to welcome different narratives, even if they are foreign or uncomfortable to us? And above all: can we still ask art to be a place of truth, even when this truth destabilizes us?

The Sabsabi case is not just a passing controversy that has since receded, but an opportunity to reflect on what artistic freedom means today. Is art really free if it must adapt to criteria of political expediency? Is the art world really inclusive when it silently excludes voices that do not conform to dominant expectations? At a time when the Venice Biennale continues to offer itself as a barometer of global culture, the initial removal of 99 Names carried the weight of unresolved contradiction. And perhaps, rather than an answer, what we are left with is a question: are we still willing to defend art that makes us uncomfortable? Or do we prefer that which only confirms us in what we already think we know?

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.