Over the past two decades, war has become a frequent and silently accepted circumstance in the West - although formally deprecated in words, both by citizens and the political class of various countries - all the more so in cases where it is not visible and does not directly touch the country’s economic or geopolitical interests. War events about which there is no news or which the news world does not tell do not exist in the eyes of the public, despite the fact that the infosphere determines a dizzying information exchange and the news is continuous and superabundant (although too often of little significance or pure entertainment). In general, it is evident that both governments and entities such as the arms industries-some of them publicly owned, not only in Italy-have every interest in diverting attention from seemingly distant conflicts, from which they can make huge profits, but in a covert form, without any direct pressure. Added to these aspects is the frequent lack of public interest in what is problematic and requires attention to be understood. Who, then, wants to hear about war? Inevitably only a more responsible section of citizens, but from a numerical point of view strongly in the minority.

The contemporary art world can react to this situation by raising citizen awareness: not so much in the typical forms of journalism, where approaches based on factual reporting and political analysis are frequently employed, but by elaborating complex tools that produce meaning with non-momentary logic, that is, without chasing the unsustainable speed of facts. At a time when the succession of events and conflicts produces an uninterrupted flow that anesthetizes and paralyzes, on the one hand it would have little result by employing the same kind of media narratives, and on the other hand there is a need for outcomes that are solid and profound, that is, that resist the rushing flow of events. Often the instantaneous modes of activism produce instantaneous, sometimes mediocre results that respond to our sense of guilt over our powerlessness, to which postmodern capitalism condemns us.

There is nothing worse than deluding ourselves into thinking that we are doing something, when in fact we are simply stroking the facts without producing anything that scratches our time. To do something of value against war is necessary, in my opinion, to seek significance without compromise. It is necessary -- let it be said without rhetoric -- to seek the masterpiece, abandoning the idea of just talking about something that happens here and now. It serves to be truly authors, coming to terms with the future, not just people responding to the loss of humanity that every war produces, moved by their own conscience - which in itself is understandable, but not sufficient. And this is as valid for curators (through exhibitions, writing, confrontation) as it is for artists with the works they can make.

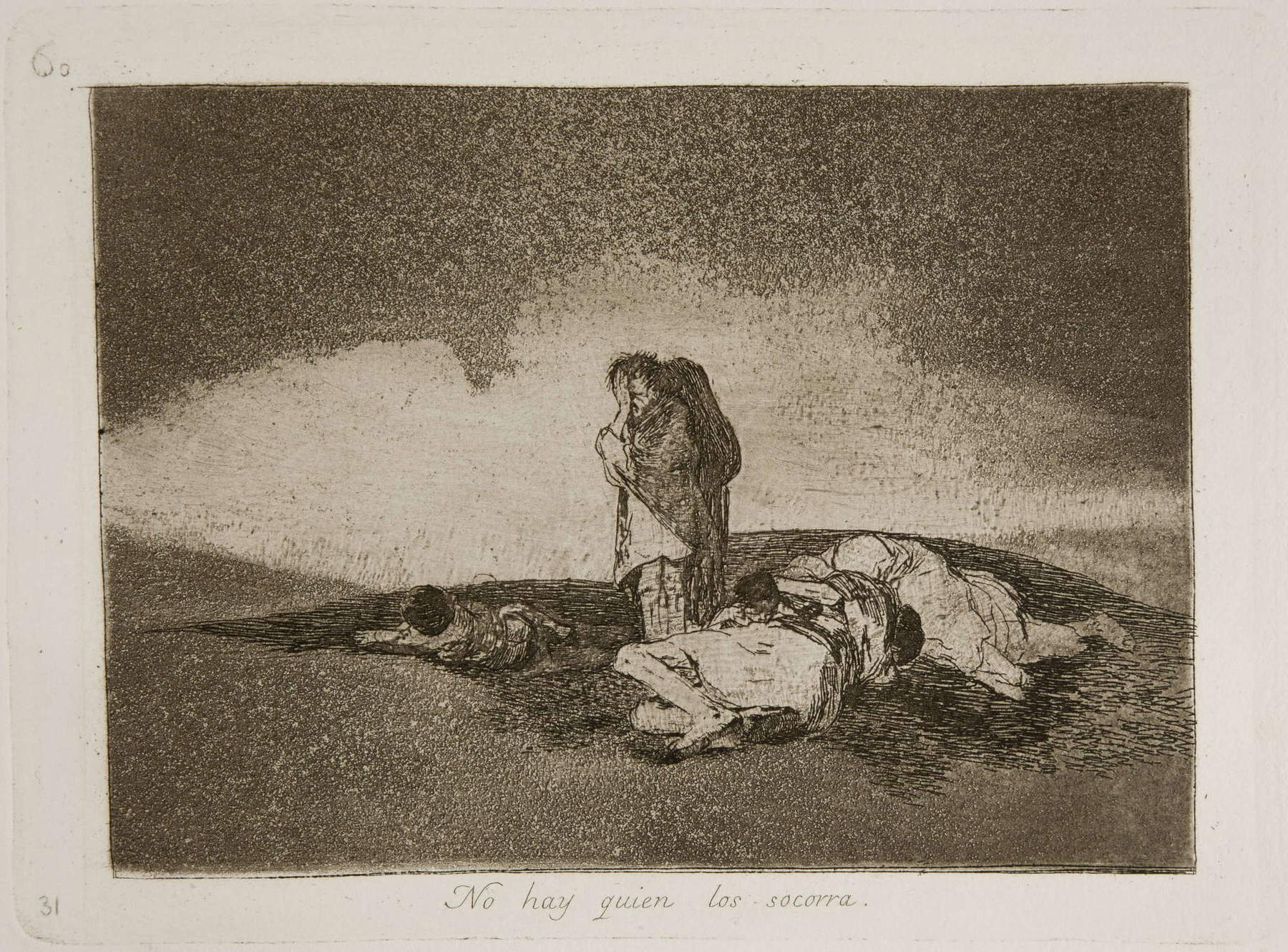

I have frequently had the impression that the art world overestimates itself in its ability to condition the world, in the most purely Marxian sense, all the more so when compared to other creative worlds such as film or even fashion. I have often seen engaged artists and curators acting politically in small contexts - real niches - where almost all people shared the content and language: elites who delude themselves that they are making meaningful operations, but who are really only speaking to like-minded people who are already aligned on that worldview. This consolatory habit should be abandoned, in favor of a more extensive and popular practice. Art, to combat the idea of war, may not be able to do much, but it can still do, if it has the courage to speak to a wider audience to promote both a critique of war and an anti-military culture. Curators, and perhaps even more so artists, can do this by creating culturally powerful and meaningful devices. There is no shortage of models: from Francisco Goya to Pablo Picasso, from Slaven Tolj to Harun Farocki. For a start, perhaps, it would be enough to stop navel-gazing.

This contribution was originally published in No. 27 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on Paper, erroneously in abridged form. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.