There was a time whenart knew how to set the squares on fire. When Manet exhibited his Olympia in 1865, the Parisian bourgeoisie screamed outrage: it was not the nude itself, but the direct gaze of the model, who did not allow herself to be consumed but defied the observer. When Duchamp posed an upturned urinal on a pedestal and called it Fontana (1917), it was not just a provocation, it was a cultural earthquake. When the Futurists shouted “Kill the moonlight!” in their manifestos, they were not only rejecting tradition, they were launching a war on public taste. Scandal was the spark that forced society to look in the mirror. Today, however, what has become of that destabilizing force?

In the 1960s and 1970s, artists such as Piero Manzoni, Joseph Beuys, or Marina Abramović continued to play with the limit, to transform the body, gesture, and life itself into artistic matter. Scandal was a language: a challenge to convention, a break with markets, with politics, with morality. Today, however, the mechanism seems to have jammed. Scandal no longer scandalizes: it has become predictable, almost expected. A photograph of naked bodies, an installation of blood or stuffed animals, a blasphemy shouted in the gallery, everything appears already seen, already codified. And the audience, far from being outraged, often shrugs its shoulders. Art that was meant to be shouting becomes echoing. Is it therefore art that has lost the power to scandalize, or is it we who have lost the ability to scandalize ourselves?

![Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917 [1964]; white earthenware covered with glaze and paint, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917 [1964]; white earthenware covered with glaze and paint, 63 x 48 x 35 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/duchamp-fontain-pompidou.jpg)

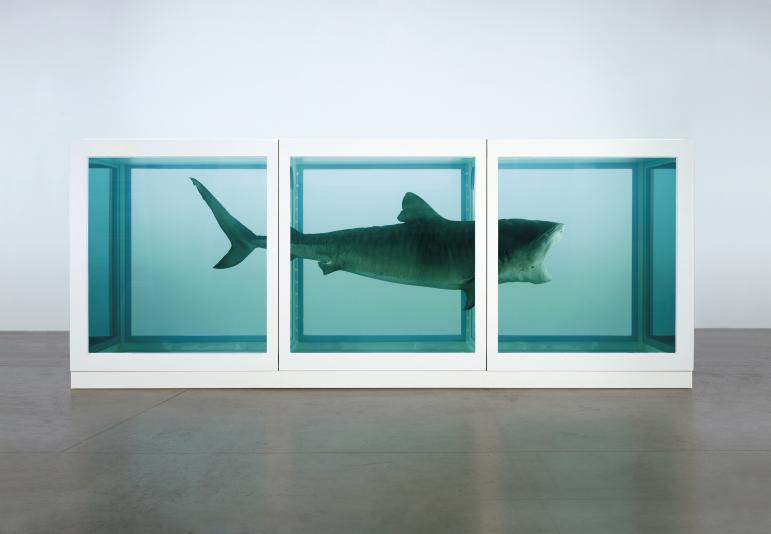

There is one fact we cannot ignore: the contemporary art market has tremendous power to absorb, neutralize and transform scandal into commodity. A work that is born to shock is immediately framed, insured, sold for astronomical sums. Damien Hirst, with his formaldehyde sharks, has made provocation a factory of millions. Maurizio Cattelan, with his Comedian (the banana taped to the wall), generated more memes than philosophical discussions, and was immediately quoted and replicated. Scandal, in short, no longer undermines the system: it fuels it. And so it becomes predictable, functional, even reassuring. What was sacrilege yesterday is marketing today.

It should also be said that we often confuse artistic scandal with media scandal. A work is discussed because it “makes the news,” not because it really touches a raw nerve in society. Art, in this sense, is in danger of being reduced to an easy provocation, a newspaper headline. But genuine scandal, the kind that shifts a boundary, that forces one to rethink the world, is something else. If Duchamp, Manet or the Futurists scandalized, it was because they touched deep questions: the relationship with the body, with morality, with time. Today, too often, artistic provocations seem to burn out in a moment, without settling.

Perhaps, however, the point is not just the art. Perhaps it is we, the 21st century audience, who have developed a kind of callus. We are accustomed to images of violence, to widespread pornography, to irreverent language circulating unfiltered on social media. In a world where everything can be seen and consumed in a matter of seconds, what can really scandalize anymore?

Our threshold of sensitivity has shifted, and with it the role of art has changed. The work that once would have rattled a bourgeois drawing room today is likely to slip between Instagram stories. Yet, the scandal is not dead: it has shifted. It is no longer in the nudity or profanity, but in its ability to touch on collective issues: climate change, migration, inequality. We are shocked not so much by the work itself, but by the political and social impact it can have. Think of the actions of activists who, in recent years, have thrown soup or paint at the glass protecting masterpieces such as the Mona Lisa or Van Gogh’s Sunflowers: they did not want to destroy the work, but to shout that art is in danger of surviving in a burning world. Is this a scandal? Or is it rather a desperate call to our indifference?

Here, then, the question opens up: if art really wants to go back to scandalizing, it must stop playing old tricks. It is no longer enough to expose a body, desecrate a religious symbol, stick a fruit on the wall. Scandal today must be thought, must generate real discussion, not just headlines. Perhaps the scandal of the future will be just that: not yet another “Instagrammable” provocation, buta work that forces us to stop, to change perspective, to question our daily anesthesia.

So what has happened to scandal in contemporary art? Perhaps it has not disappeared, but it has been transformed, forcing us, viewers, critics, curators, to revise our categories. Perhaps we are the ones who have to learn again to be scandalized, not in front of the striking gesture, but in front of the substance of things. Do we therefore want art that shakes us up, that challenges us, that forces us to think? Or are we content with art that amuses us, entertains us, reassures us under the guise of scandal? The answer, as always, is not in the galleries, but within us.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.