Contemporary art, since its beginnings, has often made provocation one of its favorite tools. To provoke means to stir, to shake, to destabilize. To trigger a friction between the work and the viewer. To break aesthetic, moral, political customs. But in an age when anything can be considered offensive, when every gesture is subject to social and cultural surveillance, is provocation still legitimate? Or does it risk becoming irresponsible? This is a question that invests not only the artist, but also curators, institutions, and the public. Where does artistic freedom end? Where does responsibility to context, to society, to memory begin? Does art have the right, or even the duty, to break taboos? Or are there insurmountable ethical limits?

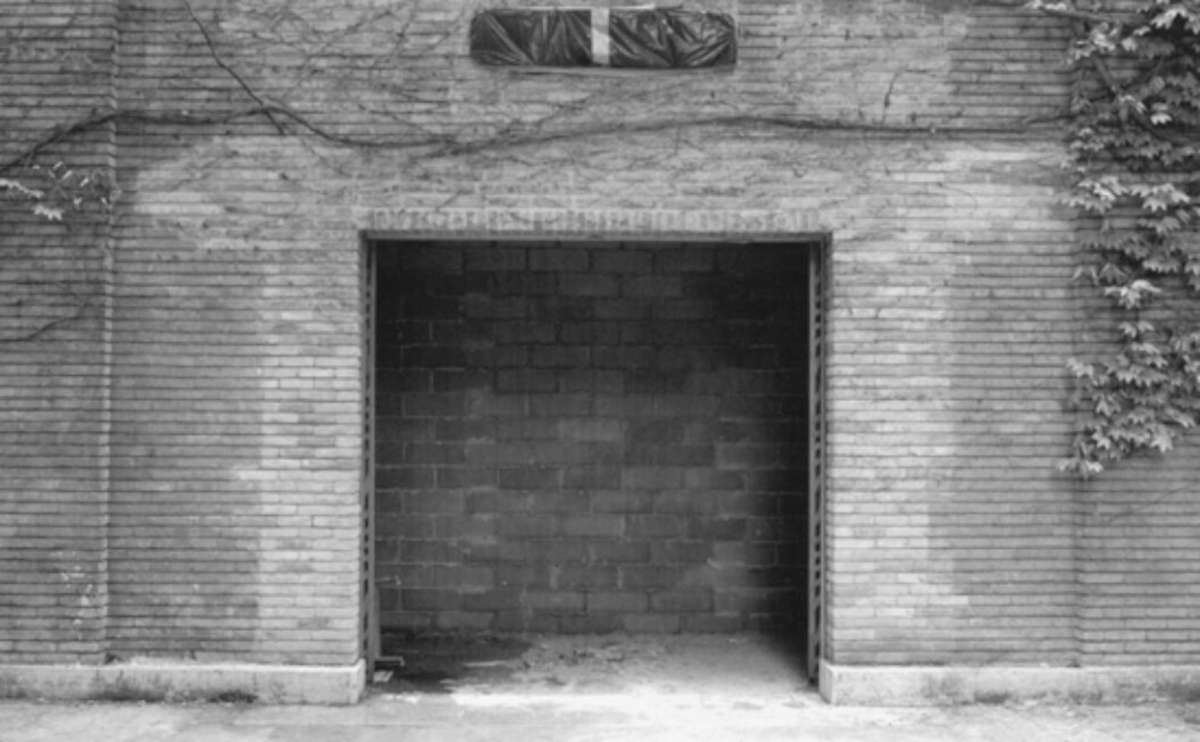

The answers are never unambiguous. But some concrete cases can help us reflect on the depth of this tension. There are provocative works that not only shake, but open a gateway of meaning. Think of Santiago Sierra, a Spanish artist known for works that stage inequality and exploitation. In 2003, at the Spain Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Sierra covered the entrance with a concrete wall, allowing access only to those with Spanish passports. The gesture was harshly criticized, but it raised a burning issue: selective inclusion in cultural and political systems. Or, take the case of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who in 2010 exhibited Sunflower Seeds at the Tate Modern in London: an ocean of porcelain seeds made by Chinese artisans. The work, in addition to its visual impact, denounced the relationship between mass production, erased individuality and invisible labor. A silent but powerful provocation.

In such cases, provocation is not an end in itself. It is thought out, argued, motivated by an ethical and political urgency. It does not seek scandal, but confrontation. It does not chase visibility, but generates real friction with the context. Different is the case with works that seem to deliberately seek the edge, more to stir up clamor than to construct a critical discourse. One example discussed is that of Belgian artist Wim Delvoye, known for his work Cloaca (2000), a machine that artificially reproduces the human digestive process, producing excrement. The work has been extolled by some as a radical reflection on consumerism and physiology, but for others it is the emblem of a sterile, self-reflexive provocation that stops questioning the viewer and becomes a pure exercise in shock. Even more problematic was the case of Tom Otterness, an American artist who in 1977 killed a stray dog as part of a performance entitled Shot Dog Film. The work, documented in a video, is still the focus of fierce controversy today. Some cities that housed his public sculptures (such as San Francisco) decided to remove them after the fact came to light. In this case, the provocation does not open a debate: it hurts. It crosses a threshold of not only ethical but civil responsibility.

Among the most emblematic examples of the debate between artistic freedom and social responsibility is Hermann Nitsch, founder of Viennese Actionism. His celebrated Orgien Mysterien Theater actions, sacrificial rituals steeped in animal blood, flesh and simulated crucifixions, have crisscrossed Europe sparking scandals, animal rights protests and accusations of blasphemy. In 2015, Nitsch’s planned work at the Madre Museum in Naples was at the center of a bitter public campaign: people spoke of “butchery exhibited as art,” of “horror disguised as culture.” However, many critics and intellectuals defended the work as a radical expression of an extreme but deeply coherent artistic language. In this case, the conflict is obvious: on the one hand, the autonomy of the artist and language; on the other, the collective sensibility. But the real problem, perhaps, is not the work itself, but the ability of institutions to mediate, to explain, to question, instead of leaving the viewer alone in the face of trauma.

While it is true that freedom of expression is a fundamental right, it is also true that no right is absolute. Every artistic gesture, when placed in a public space, museum, biennial, street, takes on a symbolic power that produces concrete effects. This is why cultural institutions have a very delicate task: to guarantee the freedom of artists, but also to ensure responsibility to the context, the publics, thesocial fragilities . This does not mean censorship, but care. It does not mean avoiding conflicts, but accompanying them. Providing critical tools, creating opportunities for confrontation, building alliances between art and thought. When controversies erupt without mediation, the problem is not so much the work as the communicative vacuum that surrounds it.

Another fundamental question is who is the object of provocation. Provoking power is a brave gesture. Provoking the voiceless can be a cruel gesture. Art that offends the margins, the victims, the fragile, risks reinforcing the very mechanisms of exclusion it is supposed to challenge. In 2019, Banksy’s Dismaland performance, a satirical Disneyland-inspired theme park, achieved great success, but it also drew criticism for trivializing the plight of refugees by including a “merry-go-round” that simulated crossing the Mediterranean by boat. Some have accused the work of turning a human tragedy into spectacle. This forces us to ask: is provocation effective when it denounces or when it spectacularizes? When it gives voice or when it exploits?

On balance, the line between freedom and responsibility cannot be definitively drawn. Each work, each gesture, each context requires a specific, careful, complex evaluation. But what we can say with certainty is that artistic freedom does not coincide with arbitrariness. The artist is not a being above the parts. He is a social actor, a constructor of meaning, a creator of imaginaries. And precisely because of this he carries with him a cultural responsibility. A responsibility that, it must be said, falls not only on those who create, but also on those who exhibit, on those who write, on those who watch. The audience is not a passive entity: it is part of the discourse. It has the right to question, to criticize, to reject. But also the duty to understand, to deepen, to contextualize. In an age dominated by instant communication, social media, and sensationalism, provocation risks becoming a shortcut. But art, the real kind, does not seek clamor: it seeks fruitful conflict, fertile doubt, openness of thought. Perhaps, then, the real question is not whether one can still provoke, but how, to whom, why. Artistic freedom is not in danger when the work disturbs, but when it stops doing so to please. And responsibility is not a brake, but a condition for giving depth, depth, and future to provocation.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.