Cortona, ancient Curtun, was one of the most influential cities ofinner Etruria. The signs of the Etruscan civilization are therefore evident both in the urban fabric and in the necropolis: in fact, it is enough to move a little farther from the historic center and enter the plain below to find here the famous tumuli of Sodo and Camucia, together with the striking Tanelle, burial structures of the Hellenistic age. Valuable evidence of a civilization that continues to speak through the power of stone.

If within the city there are still clear traces ofancient Etruscan Cortona, such as the mighty walls, the mullioned gate, and a system of underground structures such as thevaulted arch of palazzo Cerulli Diligenti, the barrel vault of via Guelfa, and the Etruscan wall of palazzo Casali, it is, however, in the surrounding area that one finds the most relevant funerary structures, designed to celebrate the prestige of the local aristocratic gentes . Here survive the so-called “Meloni,” so named because of their hemispherical shape: Etruscan burial mounds from the Archaic period that represented a clear and recognizable status symbol for aristocratic families, the principes of the 6th century B.C., or members of the most important families of the local Etruscan aristocracy. This type of burial was built on a vast circular base of large stones, above which the chamber tomb was built, structured like a real apartment with walls and corridors. Only later was the entire construction entirely covered with earth, creating the characteristic hillock shape.

The area of greatest archaeological significance is located at Sodo, along the SS. 71 in the direction of Arezzo, about two kilometers from Camucia. Here are Tumulus I and Tumulus II of Sodo, two of three burial mounds still preserved today, alongside a third mound located in nearby Camucia.

Among the three monuments, Tumulus II del Sodo stands out for its exceptional monumentality and magnificence. Dated between 580 and 560 B.C., it has a diameter of about 60 meters and consists of two tombs. What makes Tumulus II truly special is the scenic forepart, which can be interpreted as an altar-platform: this consists of a spectacular sandstone staircase and a wide platform above. Consisting of ten steps, the staircase is adorned laterally with a balustrade richly decorated with refined monumental palmettes, while the side sashes bordering it end with copies of two imposing sculptural groups (the originals of which are preserved at the MAEC in Cortona), depicting a struggle between humans and animals.

On the opposite bank from the steps are the two chamber tombs of Tumulus II. Tomb 1 is coeval with the foundation of the mound (580-560 BC). It features a long access corridor that led into two consecutive rectangular vestibules, from which six side chambers (three on each side) and the main chamber at the back were accessed. Particularly evident in these burial chambers is the pseudo-vault closure, made of large projecting slabs that gradually approach each other until the final vertical closure. Tomb 2, on the other hand, is about a century later than the creation of the first tomb and the mound itself; it can therefore be dated to around 480 B.C. and was discovered and explored in 1991. Its structure is unusual for the Cortona area, being composed of two simple consecutive chambers. This tomb has yielded artifacts of extraordinary quality, including stone sarcophagi, cinerary urns, and about a hundred pieces of fine jewelry, including necklace vains, pendants, earrings, and rings.

Tumulus I of the Sodo, also dated between 580 and 560 B.C., was discovered in 1909. The tomb is accessed through an uncovered corridor(dromos) that leads to the architraved doorway to the five burial chambers: one located at the back, centrally, and the other four arranged on either side of a central corridor. It was part of the possessions of the Cortonese countess Giulia Baldelli Tommasi and was used as a kind of quarry for building materials, thus risking being completely lost. For this reason, in 1911 the countess decided to donate it to theAccademia Etrusca, which arranged for the area to be fenced off and planned a restoration and arrangement, which was completed in the 1920s. The tumulus tomb is part of the Archaic necropolis of Sodo, probably developed at a time when the city of Cortona was not yet fully structured. It was linked to one of the most influential gentes in the area, whose prestige derived from the possession of land and control of the main communication routes.

Research conducted by Superintendent Milani in the early twentieth century recovered only a few fragments (now preserved at the MAEC) of an originally very rich trousseau, now almost entirely lost. The tomb was reused in the Hellenistic period, as shown by an inscription on the lintel of one of the side chambers that mentions two individuals: the owner Arnt Mefanates , who around the fourth century B.C. reused the tomb for himself and his wife Velia Hapisnei.

Then there is the Tumulus of Camucia: discovered in 1840 by the Tuscan archaeologist Alessandro François (and for this reason it is also known as Tumulus François), it is located in the center of Camucia, between Via Ipogeo and Via Etruria, squeezed between dwellings to the point of being difficult to recognize. It originally stood along an ancient route leading to Cortona. Dating from the 8th century BC (it is in fact perhaps the oldest), it has a circumference of more than 200 meters and partially exploits a natural hill, the rock of which was shaped to build the circular drum. The structure was characterized by a massive drum and a hemispherical cover composed of stone flakes covered with a layer of clay and topsoil, giving the mound the appearance of a hillock.

Two multi-chamber tombs were found inside. Tomb A consists of a long corridor leading to a vestibule covered by projecting vaults; on either side of the vestibule are two single cells, while in front extends the main body, consisting of two bipartite cells. All the rooms are covered by projecting pseudo-vaults closed above by horizontal slabs.

Tomb B, discovered in 1964 thanks to Piera Bocci Pacini’s excavations, has a central corridor on which six side cells open, three on each side; the terminal cell constitutes an extension of the corridor itself. The masonry is made of small and medium-sized stones, sometimes covered with slabs driven into the ground.

The materials of the recovered grave goods are now preserved and exhibited at the MAEC. Among the most significant finds is a burial bed composed of three tufa blocks placed side by side and resting on shaped legs. The front of the bed is decorated with a bas-relief depicting a funeral mourning scene: eight kneeling female figures, with the two central ones covering their faces and the others beating their chests. The style of the figures recalls that of bas-relief-decorated manhole cippus from the second half of the 6th century BCE. The bed thus holds important cultural-historical significance, offering valuable evidence of the funeral cults practiced in Etruria during this period.

In addition to the Meloni del Sodo and Camucia, the Cortona area also holds the Tanelle, less imposing but architecturally remarkable tombs dating from the Hellenistic period (late 3rd-2nd century BC). The most famous is the Tanella of Pythagoras. Its curious appellation derives from a historical misunderstanding, created because of the similarity of the ancient names of Cortona and Crotone, a city in Magna Graecia where the philosopher Pythagoras actually lived. It has been known since at least 1566, when it was visited by Giorgio Vasari.

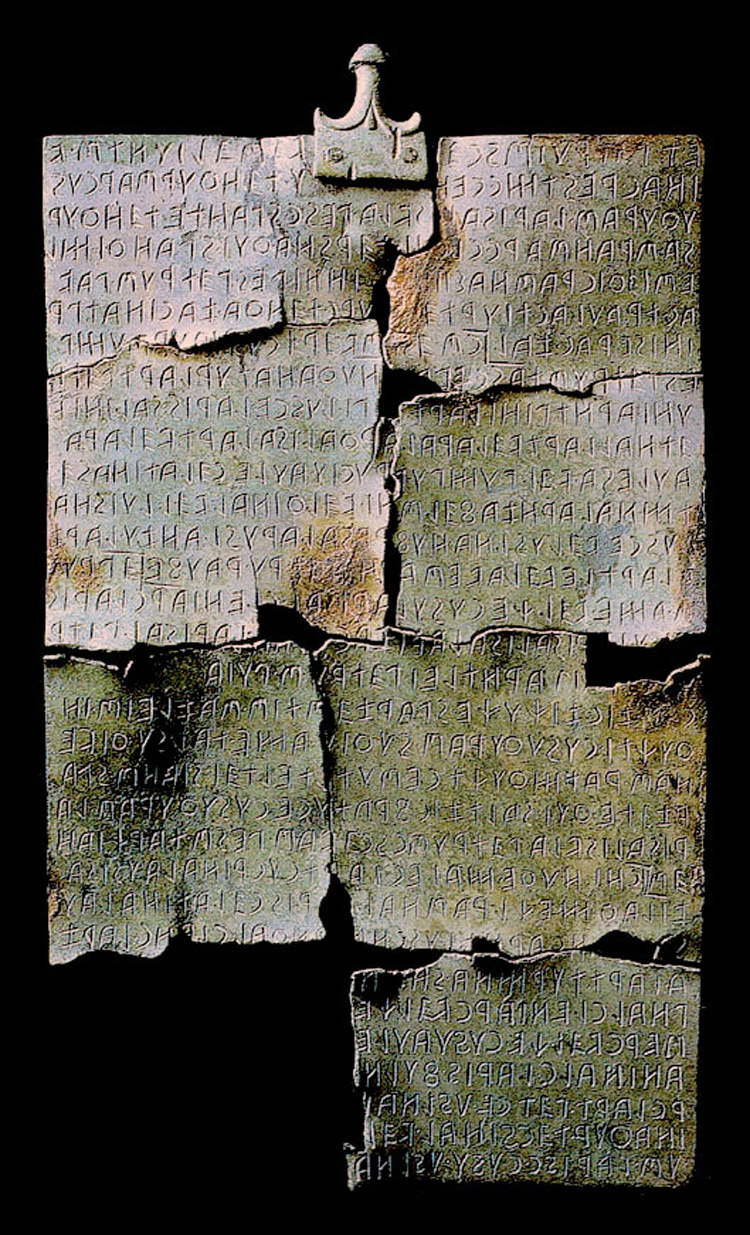

It is the most famous Etruscan monument in Cortona: an Etruscan tomb built entirely in the Hellenistic period (2nd century BC). It belonged to the Cusu family, one of the city’s best-known gentes, also mentioned in the famous bronze Tabula Cortonensis preserved at the MAEC, on which is engraved a long legal text in Etruscan concerning the buying and selling of property between the Cusu family and Petru Scevaś. The Tanella of Pythagoras, a rectangular-shaped chamber along the walls of which open loculi that housed cinerary urns, is set on a circular base and is surrounded by a cylindrical drum of large sandstone blocks. The tomb has always remained visible on the surface, although systematic excavations to bring it fully to light date only from the first half of the 19th century. Following restoration and landscaping of the access and surrounding area, in 1929 the owner, Countess Maria Laparelli Pitti, decided to donate it to theAccademia Etrusca, to which it still belongs.

Also in the vicinity of the Tanella di Pitagora is the Tanella Angori, named after the owner of the land where it was found. The tomb dates back to the second century B.C. but was discovered in 1951. On the outside, the lower part of the crepidine, or base of the monument, is visible, along with some of the crowning blocks. Inside, however, the paved floor of the burial chamber is still preserved. The base, cylindrical in shape, rests on a circular plinth more than ten meters in diameter and was originally built with boulder blocks.

And finally, the Tomb of Mezzavia, an Etruscan chamber tomb excavated in tuff, discovered in 1950 in a small oak forest located at Il Passaggio, near Mezzavia (Cortona).

Taken together, the Sodo and Camucia Tumuli, Tanelle and chamber tombs in the Cortona area constitute one of the most important Etruscan archaeological complexes in central Italy. Indeed, these monuments provide a concrete view of Etruscan funerary architecture between the Archaic and Hellenistic ages, while the precious artifacts and objects found in these tumuli, which are now preserved and exhibited within the MAEC, the Museum of the Etruscan Academy and the City of Cortona, allow us to connect the burial spaces to the objects and rituals that animated them.

|

| The tombs of Cortuna: a journey through the necropolis of the Etruscan city |

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.