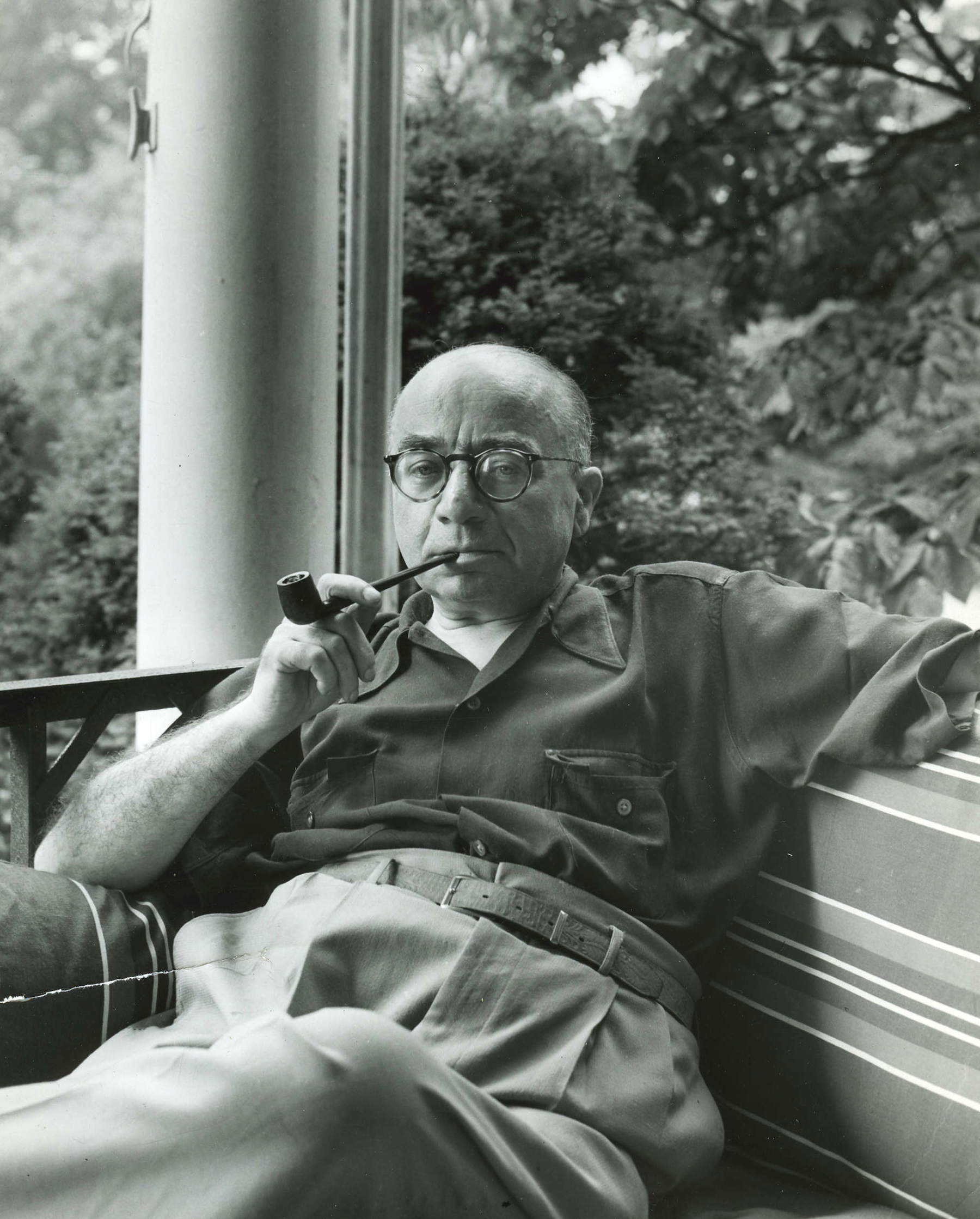

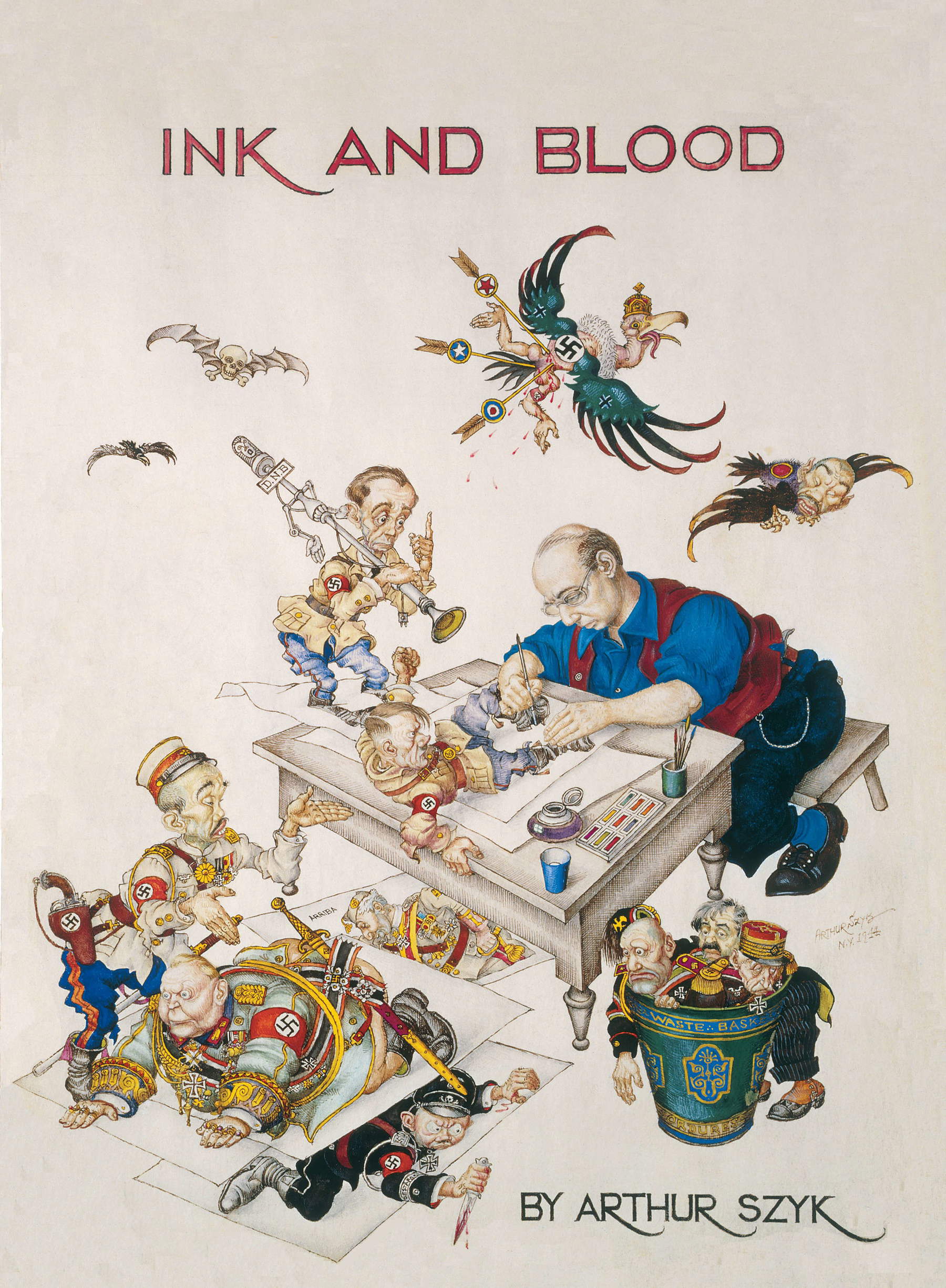

A man bent over a drawing board as the whole world seems to be sliding into the abyss. In his hand a small nib dipped in ink: this is how Arthur Szyk (Łódź, 1894 - New Canaan, Cunnecticut, 1951) portrays himself on the title page of Ink and Blood, a collection of cartoons and caricatures of the Axis Powers published in 1946, after World War II. The warlike, animated figure of Adolf Hitler seems to come to life directly from his pen; standing on the table, controlling the scene, appears Joseph Goebbels, Nazi propaganda minister, holding a microphone from the German Press Office. Pictured on the floor in front of the desk are Hideki Tojo, Japan’s prime minister, standing; Hermann Göring, Reichstag president, vice-chancellor, and minister of the Air Force, kneeling; and Heinrich Himmler, SS chief, lying on the floor. Under the desk, however, is Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. In the basket are Henri Pétain, head of the Vichy government in France (right), Pierre Laval, another Vichy official, in the center, and Benito Mussolini, Italy’s prime minister, on the left. Completing the scene above Szyk’s head flies the Nazi eagle, pierced by three arrows symbolizing the Allied forces of the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union. The main figures responsible for the darkest twentieth century are represented here through the quick hand of Szyk, who with the powerful tool of caricature openly declared his denunciation against evil and his action as a soldier in art, as he called himself. An artist-activist committed against Nazism, in support ofracial equality, particularly of Jews and African Americans.

Born in Łódź, Poland, in 1894 into a well-to-do Jewish family, he trained at the Académie Julian in Paris, a progressive art school, where he received the melting pot of visual ideas, from Orientalism to decorative folk art, that would later nurture and inspire his unique style, characterized by the precision of medieval codes and the urgency of the modern political message. Returning to Poland, he continued his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, and here he also began to take an active part in the city’s social and cultural life and become politically engaged. Meanwhile, he worked as an editorial cartoonist, costume and set designer.

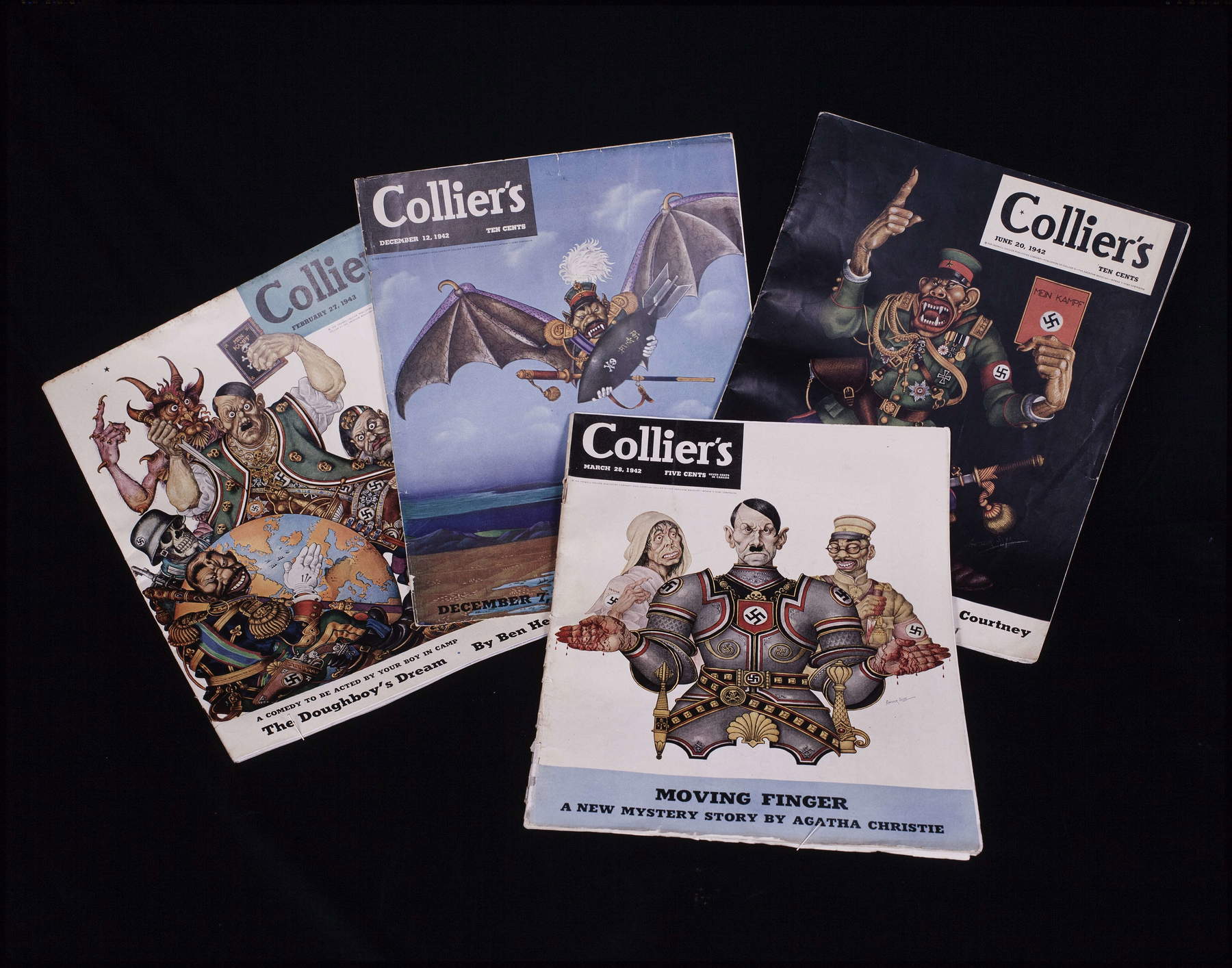

At the outbreak of World War I, he was drafted by the Russian Army as a lieutenant in a guerrilla division, and during the Polish-Soviet War the Polish Army recruited him as director of the Propaganda Department. This wartime experience forged his vision: already in 1919, with the publication of Rewolucja w Niemczech (Revolution in Germany), he had demonstrated an early ability to read the cracks in postwar Germany through satire. However, it was 1933 that changed everything: as soon as Adolf Hitler became Chancellor, Szyk had no hesitation and immediately sensed the danger that Nazism posed, not only to the Jews of Europe, but to the whole world. His commitment was total, fueled by a deep love for his Jewish-Polish roots.When he decided to move to the United States in 1940, with the support of the British government and the London-based Polish government-in-exile, he did so to fight a personal war for the survival of democracy and Jews in Europe. He became a “soldier in art” serving the Allied cause, convinced that art had a duty to mobilize consciences and push America to intervene in the conflict. In 1941, he published The New Order, a collection of his caricatures, the first anti-Nazi book of its kind, thanks to the American publishing house GP Putnam’s Sons where the subjects were shown as grotesque icons of evil and ridicule; on the title page were caricatures of Hermann Goering, Benito Mussolini and Hideki Tojo. Szyk’s caricatures invaded American popular culture, appearing on the covers of magazines such as Time, Esquire, Collier’s and Look.

With lucidity, Szyk understood that Nazi anti-Semitism wanted extermination by its very nature and that Jews were being deported and killed simply for existing. With his covers and cartoons, Arthur Szyk wanted to raise American awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust, to arouse compassion for the victims by denouncing the suffering of the innocent, but above all to lead to “action, not pity” to stop those heinous cruelties. Each stroke of his ink was an act against indifference: his images appeared everywhere and made him probably the most important artistic advocate for the liberation of Jews from occupied Europe.

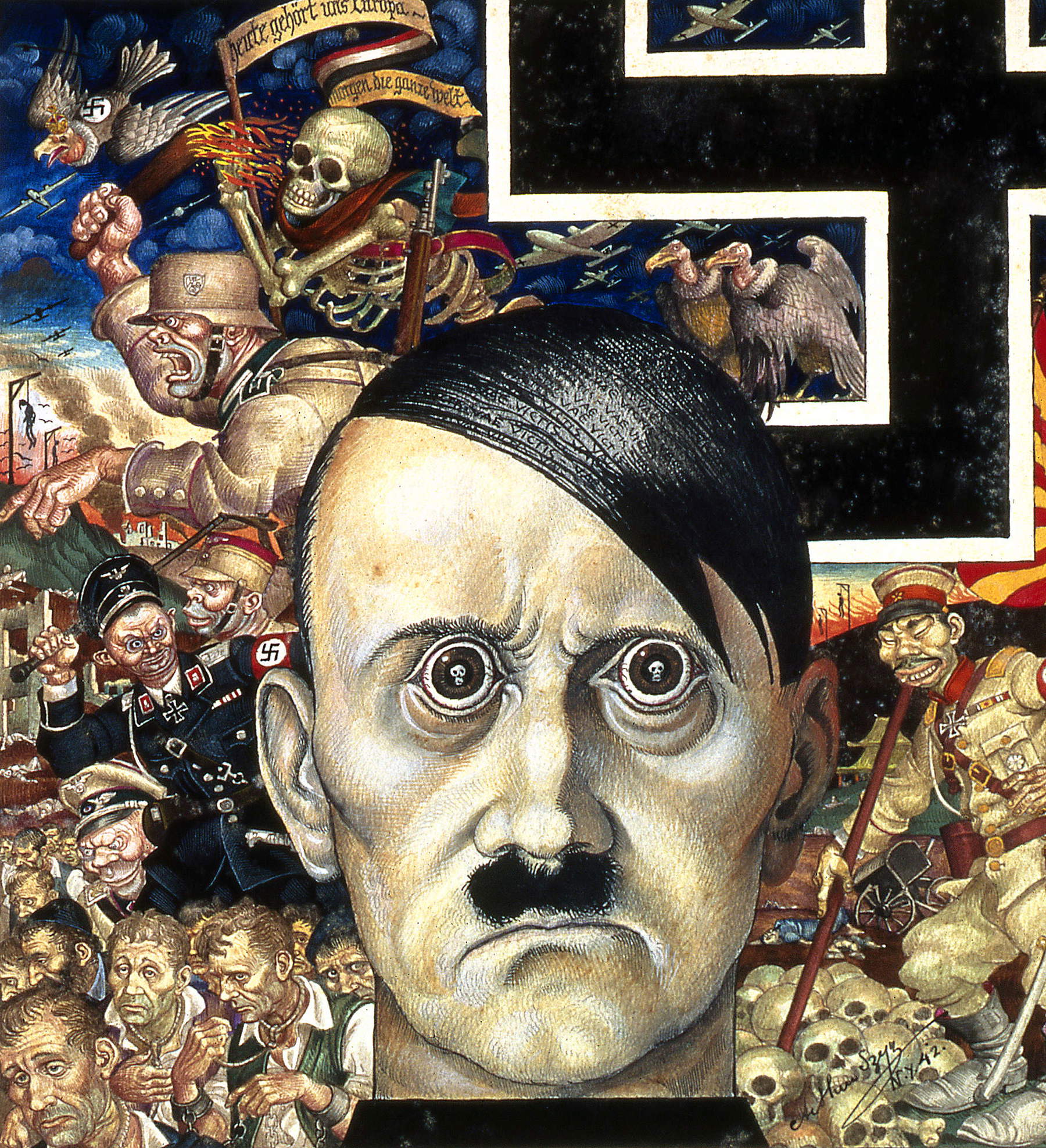

His Antichrist is from 1942: Adolf Hitler is depicted here in close-up by Arthur Szyk with skulls in the pupils of his eyes and the Latin formula Vae Victis (woe to the vanquished) written in his black hair. The work, executed in watercolor and gouache, is highly detailed and consists of a scene crowded and disturbing with references to the war: Nazi soldiers in uniform, chained, hanged prisoners in the background, vultures, airplanes in the sky, a group of skulls on one side and above a skeleton brandishing a banner on which appears the phrase “Heute gehört uns Europa / morgen die ganze Welt” (today Germany is ours, tomorrow the whole world). From the same year is Satan Leads to the Ball, in which Arthur Szyk caricatured the main leaders of the Axis Powers of World War II between Death and Satan: a Valkyrie is the personification of Germany, Benito Mussolini without pants and with holes in his shoes, Philippe Pétain and French Prime Minister Pierre Laval, Death in a helmet, Hermann Göring, and Adolf Hitler with Mein Kampf; the obese capitalist represents German heavy industry, wearing a Bavarian hat, the slogan Wir sind das Herrenvolk, and a Nazi Party pin; Joseph Goebbels carrying in his hands a box from which comes a spring-loaded clown depicted with communist red star, hammer and sickle, Phrygian cap and “Jewish nose”; Wilhelm Keitel, German field marshal of World War II; Erich Ludendorff, German general and nationalist of World War I; Joachim von Ribbentrop, German foreign minister, in black SS uniform; and Hideki Tojo with Mitsubishi sword.

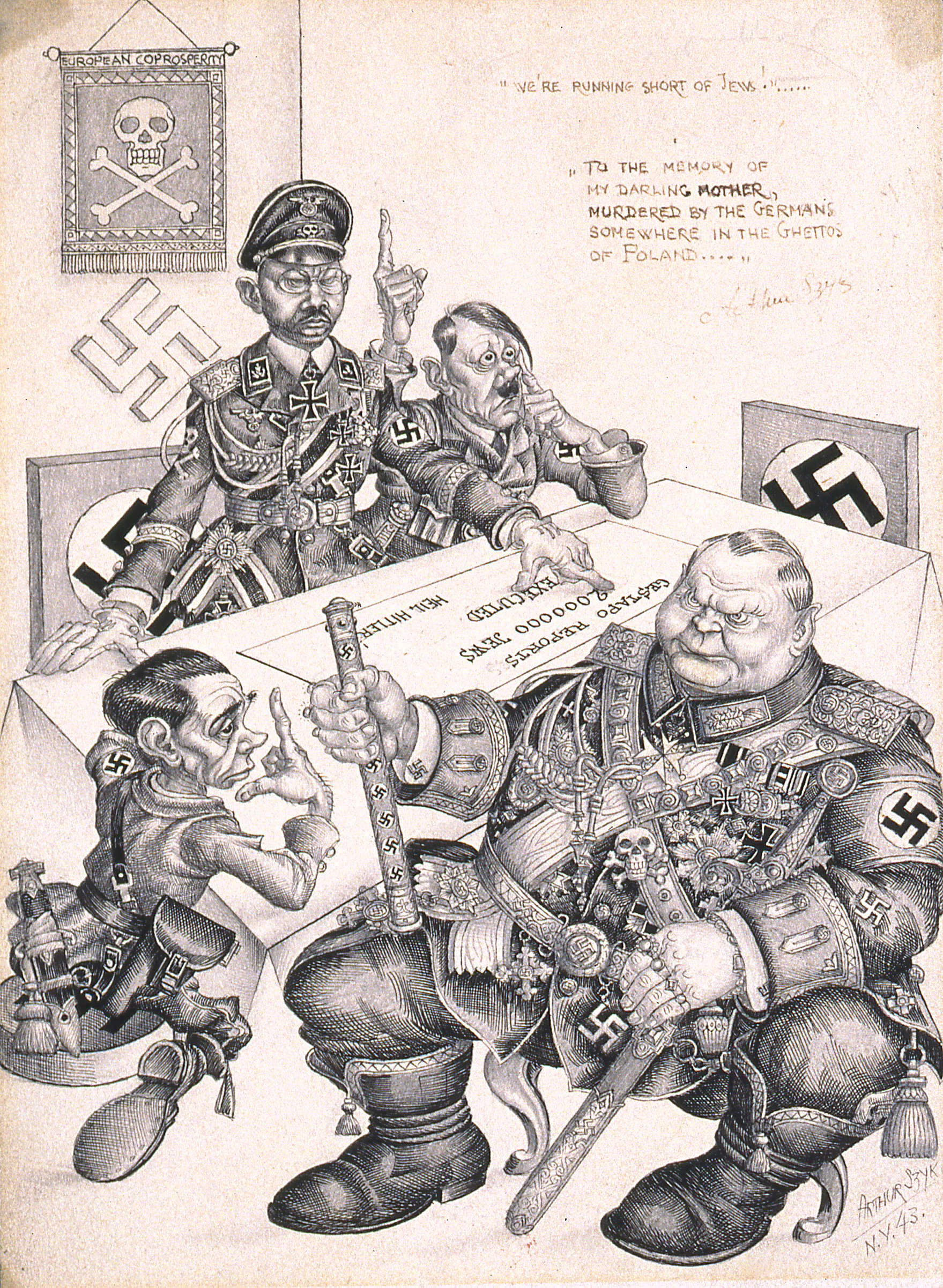

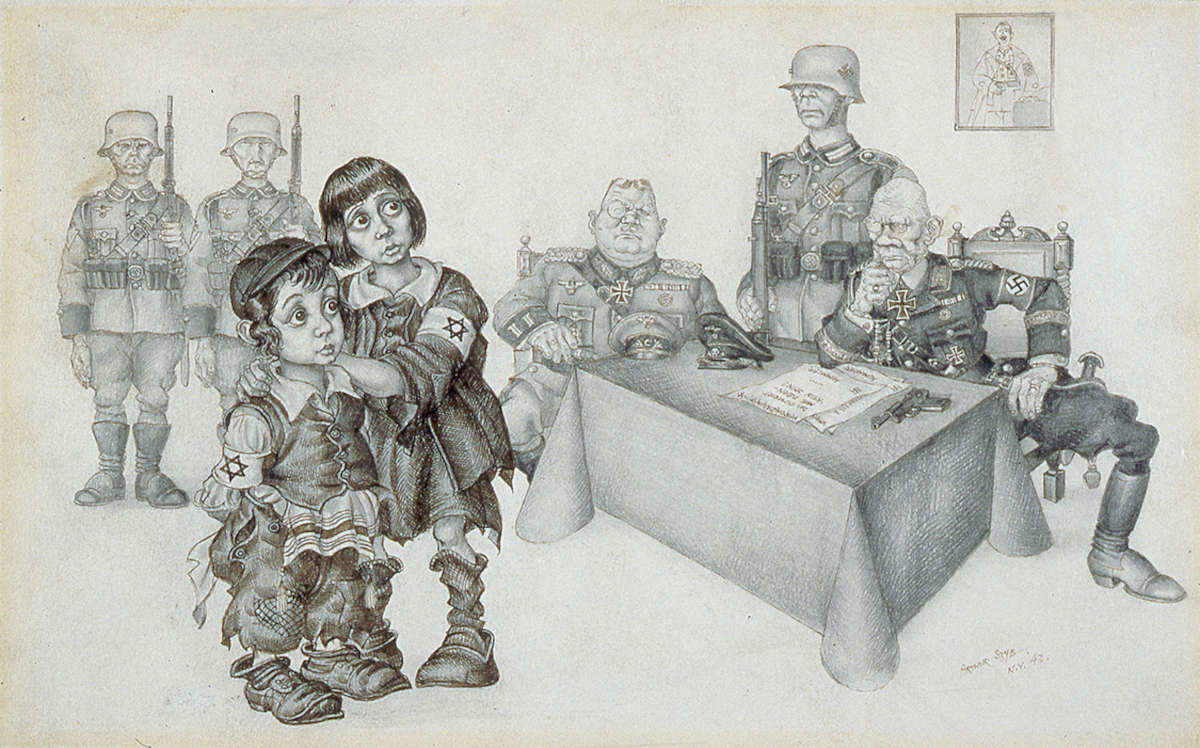

Of the following year, however, are We are running out of Jews, dedicated to his mother “killed somewhere by the Germans in the ghettos of Poland,” in which Hitler, Göring, Goebbels and Himmler, with unhappy faces, are gathered around a table on which is written “Gestapo reports 2,000,000 Jews executed. Heil Hitler,” thus highlighting the extermination of Jews planned by the Nazis, and Being shot as dangerous enemies of the Third Reich, where they denounce how the Nazi final solution does not stop even in front of children.

After the war Arthur Szyk left New York and settled with his family in New Canaan, Connecticut, where he remained until his death. Part of his intensive output of caricatures and cartoons was collected and published in 1946 by Heritage Press in the volume Ink and Blood: A Book of Drawings. Abandoning militant satire with the end of the war, Szyk resumed his work as an illustrator, devoting himself to the great classics such as Andersen’s Fairy Tales and Canterbury Tales. In 1948 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. The balance Arthur Szyk had achieved in the postwar period soured sharply in 1949, however, when he learned that he had been reported as a suspicious and subversive subject by the House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities. From that time his health deteriorated rapidly: within a short time he was stricken by repeated heart attacks. He died in September 1951, likely worn down by the pressure generated by the ongoing investigation. The allegations later proved to be completely without merit.

Although his fame faded after his passing, the rediscovery of his work since the 1990s is also due to the Arthur Szyk Society founded in Orange County, California, by George Gooche , who rediscovered Szyk’s works. Since 1997, the Society has been relocated to Burlingame, with a new Board of Directors led by Irving Ungar, the world’s foremost expert on Arthur Szyk’s art, and until 2017, when it was dissolved, its activities led to the organization of exhibitions, lectures, and publications.

Arthur Szyk teaches that indifference is the soil on which tyranny grows and that every individual has a duty to use his or her talents to defend humanity. His caricatures are testimonies against forgetting, reminding us how memory is not a passive act, but an ongoing battle that is fought with the courage not to remain silent in the face of absolute evil. Remembering Arthur Szyk therefore means remembering not only the artist, but the man who chose to act so that the world could not say it did not know. On this Remembrance Day, his works still look back at us, asking if we are ready, like him, to put our ink to the service of freedom. We are.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.