From the post-World War II period until the early 2000s, Italian fashion built its public identity through a complex bond of communicative tools and aesthetic codes that today represent the heritage of the national imagination. Of great importance, therefore, is the role of advertising vehicles in those years, that is, the means through which fashion transmitted values, innovations and aspirations, transforming itself into an expressive platform capable of redefining years and lifestyles. Advertising then became a storytelling tool, a mirror of society and a creative laboratory capable of condensing the culture and desires of an entire country. In the 1950s, Italy is still undergoing reconstruction. Designer graphics found fertile ground in telling the story of fashion: essential lines and stylized signs became the language capable of interpreting the tastes and aspirations of a changing public. This is the story retraced at the exhibition Fashion and Advertising in Italy 1950-2000 at the Fondazione Magnani Rocca in Traversetolo (Parma), through Dec. 14, 2025.

The Opening of the Season poster for La Rinascente emblematically represents the season just highlighted. The female body is reduced to a curved line, the dress becomes a flowery field in motion, and the sign is synthetic and elegant. It is about 1958 and illustrator Lora Lamm, together with graphic designer Max Huber, accompanies the rebirth of Italian taste with a modern and cultured stroke, capable of combining lightness with refinement. La Rinascente, among the few large warehouses that survived the postwar period, placed itself on an almost luxury level, giving advertising a role of aesthetic and cultural vision. The 1950s are thus those years when graphics anticipate trends and an idea of style that Italy exports to the world.

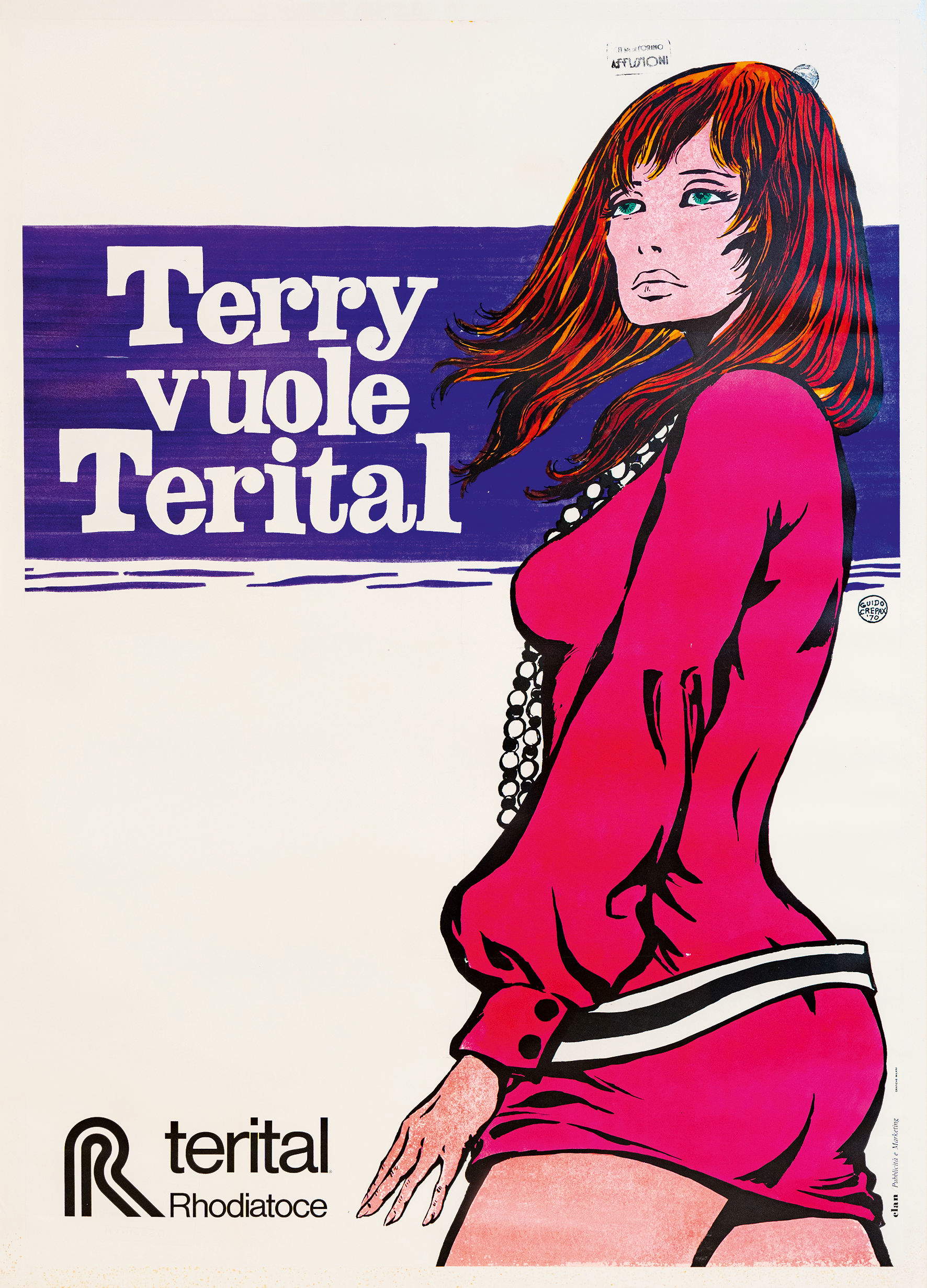

In parallel, figures such as artist René Gruau became symbols of international fashion communication. An illustrator for maisons and ateliers that shaped twentieth-century costume, Gruau frequented editorial offices and ateliers, working with Marie Claire, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Très Chic, and Vogue. His elegant, concise strokes render a sophisticated style, where sinuous lines, à plat color fields (a flat brushstroke) and calibrated compositions tell the story of feminine beauty with modernity. Gruau does not follow photography (already dominant since the 1960s); rather, he manages to surpass it and reinvents advertising graphism by experimenting with color combinations and new languages. On the national level, on the other hand, artists such as Franco Grignani, Erberto Carboni and Guido Crepax contribute to defining a recognizable canon of elegance. Unlike Grau, Crepax, with his comics and his Valentina, mixes myth and reality, drawing inspiration from the actress Louise Brooks and his wife Luisa, creating a character who interprets the multiple aspects of the female universe. Well, all the highlighted languages consolidate fashion as a symbol of a creative, modern Italy, already open to comparison with foreign countries, capable of exporting culture and style.

The 1960s then saw television establish itself as the main vehicle of communication. Carousel transforms advertising into theater. We are talking about small animated narratives, skits and songs that convey more a national custom than a product. Indeed, the Carousel succeeds in shaping the cuisine of Italian women on stage. Fashion enters the scene through everyday situations, becomes language and entertainment. And how does it do this? The example of Mina between 1965 and 1970 in the Barilla carousels is the most appropriate: directed by Antonello Falqui and Valerio Zurlini, geometric sets, clothes designed by Piero Gherardi, bangs cutting through the air, silhouettes punctuating the songs. Mina creates fashion, becomes an icon of aesthetics and style, and anticipates the transformation of the female figure into the protagonist of advertising communication.

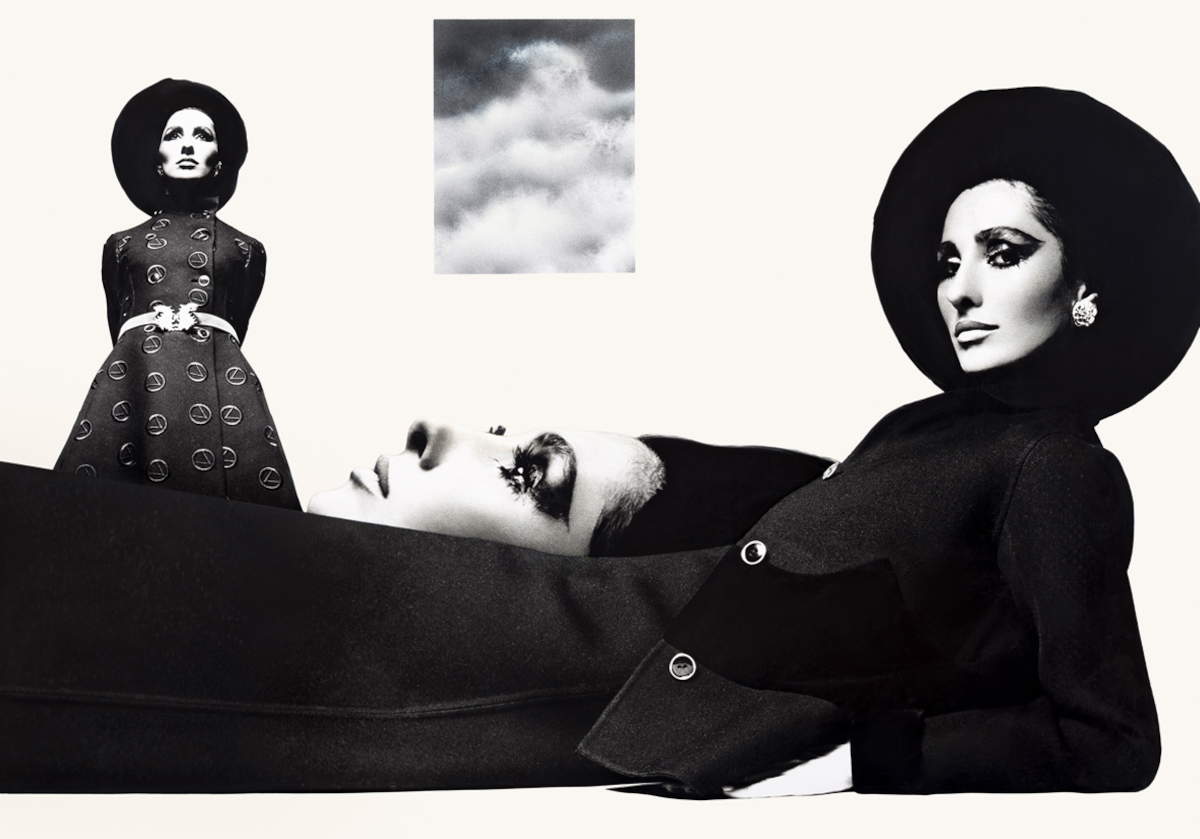

The liberalization of private networks in the 1970s then leads to a radical change. The advertising image emancipates itself from the pedagogical constraints of state television and gains immediacy and dynamism. Photography becomes a narrative tool rather than mere documentation:GianPaolo Barbieri, Giovanni Gastel, Maria Vittoria Backhaus and Alfa Castaldi construct atmospheres, beauty codes and languages capable of intercepting changes in the body and society. The campaigns thus propose ways of living and being that transform Italy into an international laboratory of style. It is 1973, Oliviero Toscani enters the game and breaks the mould with Chi mi ama mi segua. The slogan becomes a clear and direct manifesto. Here the product, in this case we are talking about Jesus jeans, disappears, what remains is the strength of the image, its provocation and beauty. In the 1980s and 1990s, the artist redefines the imagery of society: he uses photography to shake public opinion and bring issues such as racism, the death penalty, AIDS, war, sex, violence and anorexia to the center of debate. Advertising then becomes politics, art, religion and philosophy together. Indeed, it manages to create cultural short circuits that mark the entire era. In any case, in this season Italian fashion achieves an unprecedented global force. We are talking about electric colors, bold logos, and the confidence in the future that characterize a creative decade that influenced styles and aesthetics that are still recognizable today.

Around the 1990s, designers Dolce & Gabbana reinterpret neo-realism in a pop key; Moschino plays with irony, criticism and subversion; Marras weaves poetry and roots; Diesel instead uses the language of rebellion. The fashion of artists and designers translates into a vision, culture and a way of thinking about the future. Fashion houses such as Armani, Versace, Ferragamo, Coveri, Benetton, Fiorucci, Gucci, Max Mara, and Valentino develop distinct and recognizable visual identities. Armani chooses formal purity, Benetton entrusts its identity to Toscani’s provocative gaze while Versace explores sensuality and power. The Calabrian designer transformsclassical art into contemporary figures: this is the case of Medusa who becomes the emblem of charm and seduction, overturning stereotypes and combining tradition and novelty. His integrated approach blends advertising campaigns, publishing, international celebrities, and theatrical fashion shows. With photographers like Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton and supermodels like Naomi Campbell, Claudia Schiffer, and Cindy Crawford, Versace’s fashion becomes a global marketing tool. Fiorucci then introduces a pop energy that anticipates a global youth style. In this wake, a pop bazaar space defined as a daytime disco is then born in Milan, which becomes a laboratory of contamination combining fashion, art and music. Neon posters, ironic gadgets, shiny jeans, performance art, and iconic references such as the angels from Raphael ’s work Madonna Sistina (created between 1512 and 1513) shape fashion into pop language.

Therefore, what does it mean to look back over fifty years of advertising? It means observing how Italy has narrated itself through fashion. The economic boom to the consumer society, the youth revolution and the 2000s, represent social transformations that are reflected in advertising codes. The body becomes central, the brand establishes itself as a status symbol, desire evolves from narrated to exhibited, and the first traces of digital communication begin to appear. Fashion advertising, seemingly considered a marginal or frivolous phenomenon thus becomes a field where trends, ambitions and contradictions of an ever-changing Italy are concentrated.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.