When was the first conscious use of the word “museum”? The modern meaning of the term by which today we refer to that nonprofit institution serving society that, taking up the definition of Icom formulated in 2007, “carries out research on the tangible and intangible evidence of man and his environment, acquires, preserves, and communicates it, and specifically exhibits it for purposes of study, education, and enjoyment,” has a precise date of birth, 1543: this is the year in which, in Como, the construction of the Borgovico Museum was completed, the building that the humanist Paolo Giovio (Como, c. 1483 - Florence, 1552) had earmarked for his collection of about four hundred portraits of illustrious ancient and modern personalities: princes, emperors, popes, men of letters, condottieri, artists, and poets.

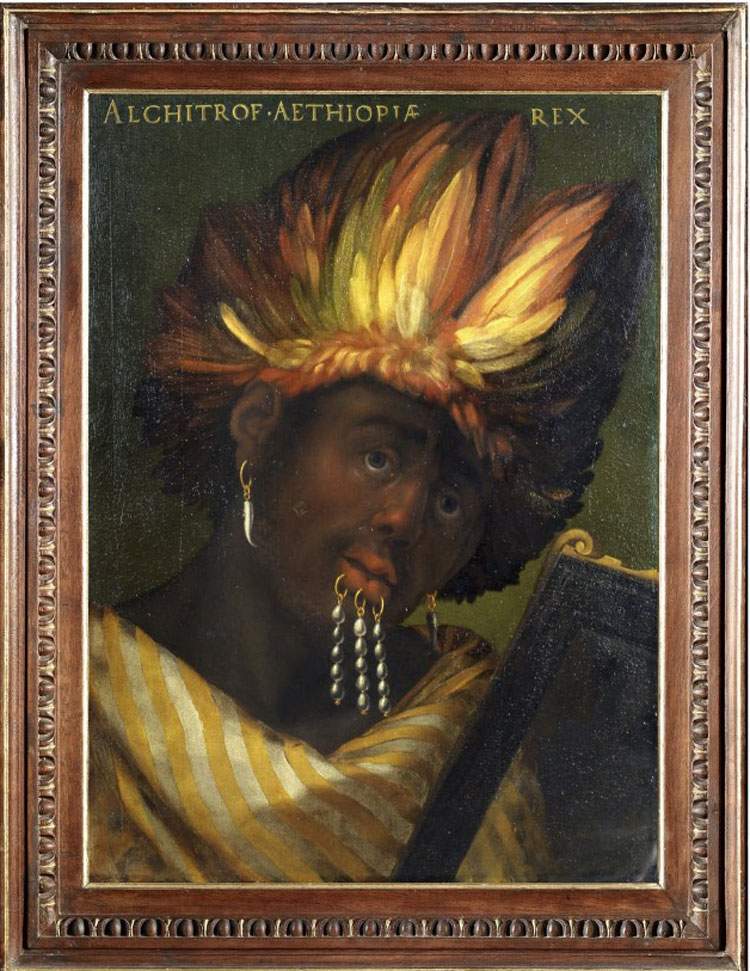

Giovio had begun to start the collection that would become his Musaeum before 1520, when he began acquiring portraits of literati, to which he later added those of princes and condottieri. These were first and foremost contemporary figures: wherever possible, Giovio wanted the portraits to be executed from life, and in this regard he not infrequently made direct contact with the figures or those who knew them. The same care he wanted to be taken with the figures of the past: therefore, not stereotyped portraits, but as faithful as possible to the images that had been handed down of those figures (for Roman emperors, for example, the reference was to the numismatics and medallistics of the time). As mentioned, the collection numbered about four hundred portraits of the most diverse personages: sovereigns Charles V and Francis I of France, rulers and ruled by rulers as varied as Lorenzo the Magnificent, Gian Galeazzo Sforza, and Cesare Borgia, poets such as Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Ludovico Ariosto, and Poliziano, men of letters such as Pietro Aretino and Niccolò Machiavelli, philosophers such as Pietro Pomponazzi, Pico della Mirandola, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and Thomas More, great humanists such as Lorenzo Valla, Demetrius Calcondila, Platina, and Giovanni Pontano, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

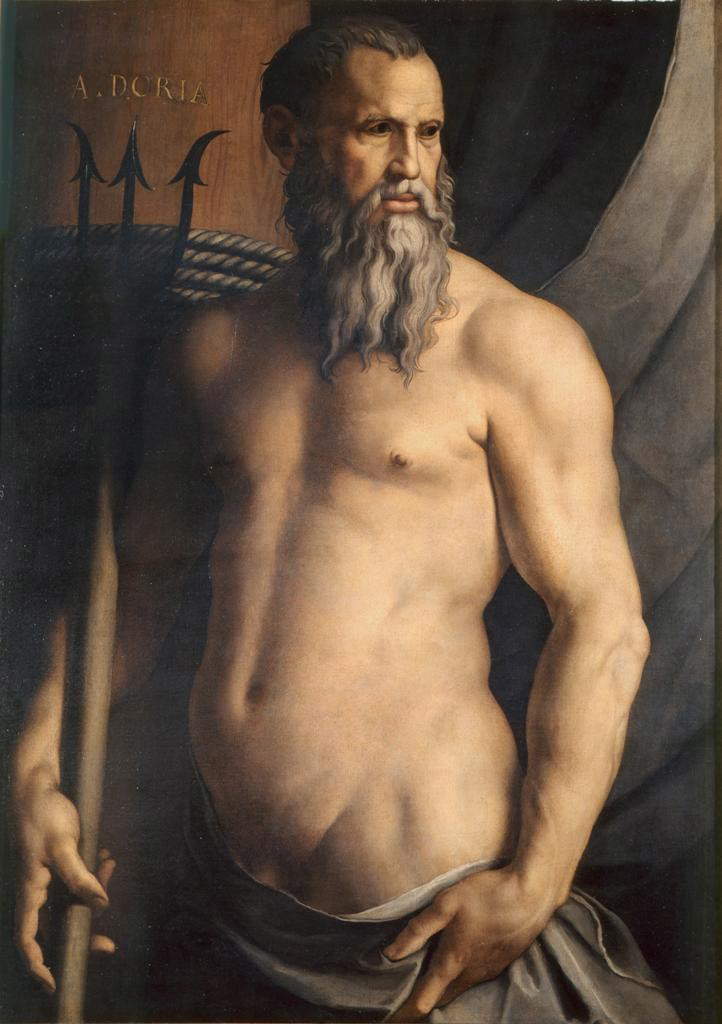

It should be premised that, after Giovio’s death, the collection did not survive intact for long: in fact, it was immediately dismembered among the humanist’s various heirs. Today, however, we know it to a large extent because as early as the sixteenth century some copies were made, the most famous of which is the celebrated “Giovian Series” in the Uffizi, commissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici, who sent one of his most trusted painters, Cristofano dell’Altissimo (Florence, 1525 - 1605) to Como to make a faithful copy of the collection. Cristofano dell’Altissimo worked for almost his entire career on copying Paolo Giovio’s collection (until 1589), executing portraits in a smaller format than the originals for logistical reasons: it was intended to make their transportation to Florence more agile. Today, the Giovian Series is displayed along the corridors of the Uffizi. The original collection (a fraction of which, comprising about forty portraits, is now exhibited at the Pinacoteca Civica di Como) was not stylistically homogeneous, although seeing the paintings of the Gioviana Series, all executed by the same hand, we might perceive it as such: in fact, many artists, some of the greatest of the time (Titian, Bronzino, Dosso Dossi, and Bernardino Campi, among others, contributed to the creation of Paolo Giovio’s paintings: the most famous work in the collection is perhaps Bronzino’s Portrait of Andrea Doria in the guise of Neptune, now in the Pinacoteca di Brera), and other craftsmen who remained anonymous, with obvious stylistic differences and even differences in setting (half-length, profile, almost full-length portraits and so on appear).

The building commissioned by the Como humanist can be considered the first one built specifically for use in what we would call, precisely, “museum” functions. And Paolo Giovio is the first intellectual to use the word “museum” in the modern sense. The choice of the building’s name harked back to the classical tradition. Literally, the “museum” is the “place sacred to the Muses,” the Greek patron deities of the arts, to whom an entire hall was dedicated. Giovius was not the first to adopt the term: in fact, he was preceded by others such as the German humanist Cuspinianus (Johannes Cuspinian; Schweinfurt, 1473 - Vienna, 1529), who used the term in 1517 to refer to a place of study, and a few years later the term Mouseion in the Greek style would also be used by Erasmus of Rotterdam, in Convivium religiosum, to refer to a small study intended for reading codices. However, Jovius’ use of the term was entirely new and went hand in hand with his idea that, scholar T. C. Price Zimmermann, constitutes “his most original contribution to European civilization.” For if Wunderkammern and princely collections "were not new, the idea of filling a villa with portraits of famous people on canvas or on bronze medallions, calling it a museum, and opening it ad publicam hilaritatem (for public delight) was a breakthrough."

Giovius had certainly been inspired by some precedents (his collection of famous people was not the only one, although his insistence on the realism of the depictions was also unprecedented: Giovius was in fact a historian and his primary interest was therefore the verification of truth), but the idea of creating from the beginning a collection for public and didactic purposes and dedicating a special building to it had no precedent. It might be noted, for the sake of completeness, that probably the idea of opening the collection was not born in the immediate term: in fact, Pietro C. Marani and Rosanna Pavoni that “the first private museums such as Paolo Giovio’s in Borgovico on Lake Como (which boasts the record of having been built [...] next to the scholar’s villa, as a building created specifically to preserve the portraits of illustrious men, ancient and modern) were born [...] out of personal pleasure, out of a desire to systematize the world and, only later, to offer delight and opportunities for study to the ’gentilissimi et illustri signori... ai cittadini’ (Giovio).” However, it is not in dispute that many features of Giovio’s idea contribute to making him an extraordinary precursor.

“Giovio,” Zimmermann again writes, “conceived of a worldwide archive of portraits, an idea whose novelty and usefulness must have equally impressed the donors since, even taking into account his noteworthy insistence, he enjoyed a remarkably high index of acquiescence to his requests, which were certainly not economically insignificant.” In choosing the name to be assigned to the building (although as early as 1532 he had used the term “musaeum” together with his brother, the notary Benedetto Giovio, to refer to one of the rooms in the family palace perhaps intended for one of his collections) it is possible, the scholar further explains, that Giovio “had in mind something analogous to the museum founded by the Ptolemies in Alexandria, a splendidly set up academy, such as a great library and a tradition of readings and symposia in which the Hellenistic rulers of Egypt took part personally; but if so, he was not explicit about it.”

Museologist Adalgisa Lugli has summed up the Lombard humanist’s programmatic paradigm very effectively: “In the meaning indicated by Giovio museum contemperates together the building, an iconographic program, a collection, and is a monumental place, a landmark offered for the use and enjoyment of a wide circle of people. The term ’public’ also appears there in the various programmatic intentions.” It is therefore something very close to today’s idea of a museum. Moreover, a very interesting fact, for the mentality of the time, the knowledge aspect was prevalent over the preservation aspect. Two elements, in particular, help to clarify this aspect: the first is the insistence on the theme of the Muses, which also figured painted in the central hall of the building (“at the head on one side is a very miraculous hall with all the Muses painted around with its instruments, perspectives, animals, friezes and admirable figures,” the man of letters Anton Francesco Doni would have written when visiting Giovio’s Musaeum), to emphasize a sort of “sacredness” of the place and to protect the process of knowledge that would take place here. The second, on the other hand, is the presence, next to the portraits, of Elogia, or short biographies that were to accompany the portraits to make explicit the facts about the person depicted in the painting. The term chosen referred to the inscriptions that, in Roman portraits, accompanied images of the subject. The Elogia were divided by type (the first to be published, in 1546, were those of the literati). “Reprinted many times,” Price Zimmermann writes again, "the Elogia are a mine not only of biographical data, but above all of the customs of the time, judgments, rumors, even gossip, in an age that devoted itself, and in no small measure, to the creation of heroic personalities. These are short compositions that employ res gestae and oral tradition to outline the merits and flaws of a character, even taking in news that cannot be verified elsewhere today, as long as they serve to portray his essence, as contemporaries perceived him."

The site on which the building would rise was also rich in suggestion. Construction began in 1537, in an area where it was believed there was a plane tree dear to Pliny the Younger: probably the idea of coming from the same areas as Pliny (to whom the Musaeum was dedicated) also helped shape Paolo Giovio’s wishes. The humanist himself, in the Musei Ioviani Descriptio, had provided a description of the building (here in Franco Minonzio’s translation): “The villa is in front of the city and juts out like a peninsula over the underlying surface of Lake Como, which expands all around it; it juts out to the north with its square front and to the other lake with its straight sides, on a sandy and unspoiled, and therefore extremely salubrious, coast, built precisely on the ruins of Pliny’s villa. [...] Down in the deep waters, when the lake, gently spreading its glassy surface, is calm and transparent, one sees squared marbles, huge trunks of columns, worn pyramids that formerly decorated the entrance to the falcate pier, in front of the harbor.” From the main hall of the collection, Giovio wrote again, “one can see almost the whole city. You can also see the parts of the lake facing north, with their splendid inlets; the verdant shores, full of olive and laurel trees; the hills where the vine grows luxuriantly; the mountains that begin the Alps, rich in woods and pastures, but where wagons can pass. Everywhere one turns one leaps to the eye an unexpected and pleasant aspect of the region, which pleases the eye and is never cloying.”

The building itself was modeled after the Roman villa described by Pliny the Younger, with a large central hall that, in antiquity, was destined for the ancestors, while in Paulus Jovius’ structure it would have housed the Musaeum. Thanks to the research of scholars such as Paul Ortwint Rave, Matteo Gianoncelli, Stefano Della Torre and Sonia Maffei, it has been possible to reconstruct what the architecture of the house must have looked like: two-story, it was preceded by a portico that led directly to the Museum Room, overlooking Lake Como and surrounded by service rooms and other rooms dedicated to other deities. The first room one entered was a large atrium decorated with frescoes and emblems, from which one entered the cavaedium, the central courtyard around which the portico ran. From here, as mentioned, one entered the Museum Room, the largest in the house. From here one then entered the Hall of Minerva, dedicated to the illustrious Como people, which was adjacent to the Hall of Mercury, where the palace library was located. One then entered the Hall of the Sirens, intended for amusements, and from here one then reached the armory. On the second floor, however, was a Hall of Honor, flanked by Paolo Giovio’s private quarters.

Although the belief in the novelty of Giovio’s Musaeum is now firmly established, many aspects related to its conception remain to be clarified. For example, we do not know how the portraits were arranged in the Museum, although, for Franco Minonzio, wondering about this is “a false problem” because “it could be that the contingency was never given that all the portraits were in a condition to be housed at the same time,” given the vastness of the collection. “In any case, it is attested that the two family houses that Paul had restored at the same time as the building of the Museum were also lent for this purpose.” Another problem is the one anticipated by Marani and Pavoni, namely the timing of the realization of the Musaeum: in fact, the collection was started before 1520, while the construction of the building intended to house it started a good seventeen years later, and even later is the publication of the Elogia. Although, therefore, the Jovian museum is to be seen as the intersection of three distinct elements (the collection, the building, the biographies), and although it is often perceived today as an extremely regular whole, it took many years for the Musaeum to take on the characters that made it such an original idea. The problem is complex, not least because in turn the elaboration of the villa precedes the beginning of the collection by more than fifteen years. “If this is so,” Minontius writes, “it is legitimate to ask, ex novo, within what nucleus of ethical needs and intellectual reasons ledification of the Museum took shape, whether Giovio’s historiographic method had any part in the initiation of the collection of portraits of illustrious men, and thus whether or not the junction between the progressive constitution of the collection and a desire for the villa so early was occasional.” The answers could be rooted in Giovio’s long and in turn complex intellectual life, Minonzio suggests.

In any case, the building has long since ceased to exist. In fact, it fell into disrepair not long after Paolo Giovio’s death, and in 1613 it was finally demolished by the new owner of the area, Cardinal Marco Gallio, who would later have the family palace, the Villa Gallia, built there, further remodeled in the 19th century, when it took on its current neoclassical appearance. Today, with the Musaeum no longer in existence and with the original collection dismembered (the most substantial nucleus, as mentioned, is that of the Pinacoteca Civica di Como) we can consider the Uffizi’s Giovian Series as the most direct heir to the Como humanist’s project. Initially housed in the Palazzo Vecchio, it was then moved to the Palazzo Pitti in 1587, and then later transferred to the Uffizi, which, moreover, with its extraordinary collection of self-portraits, has another collection built in a spirit not dissimilar to that which animated Paolo Giovio. And which today therefore survives far from Lake Como, in the corridors of Italy’s most visited museum.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.