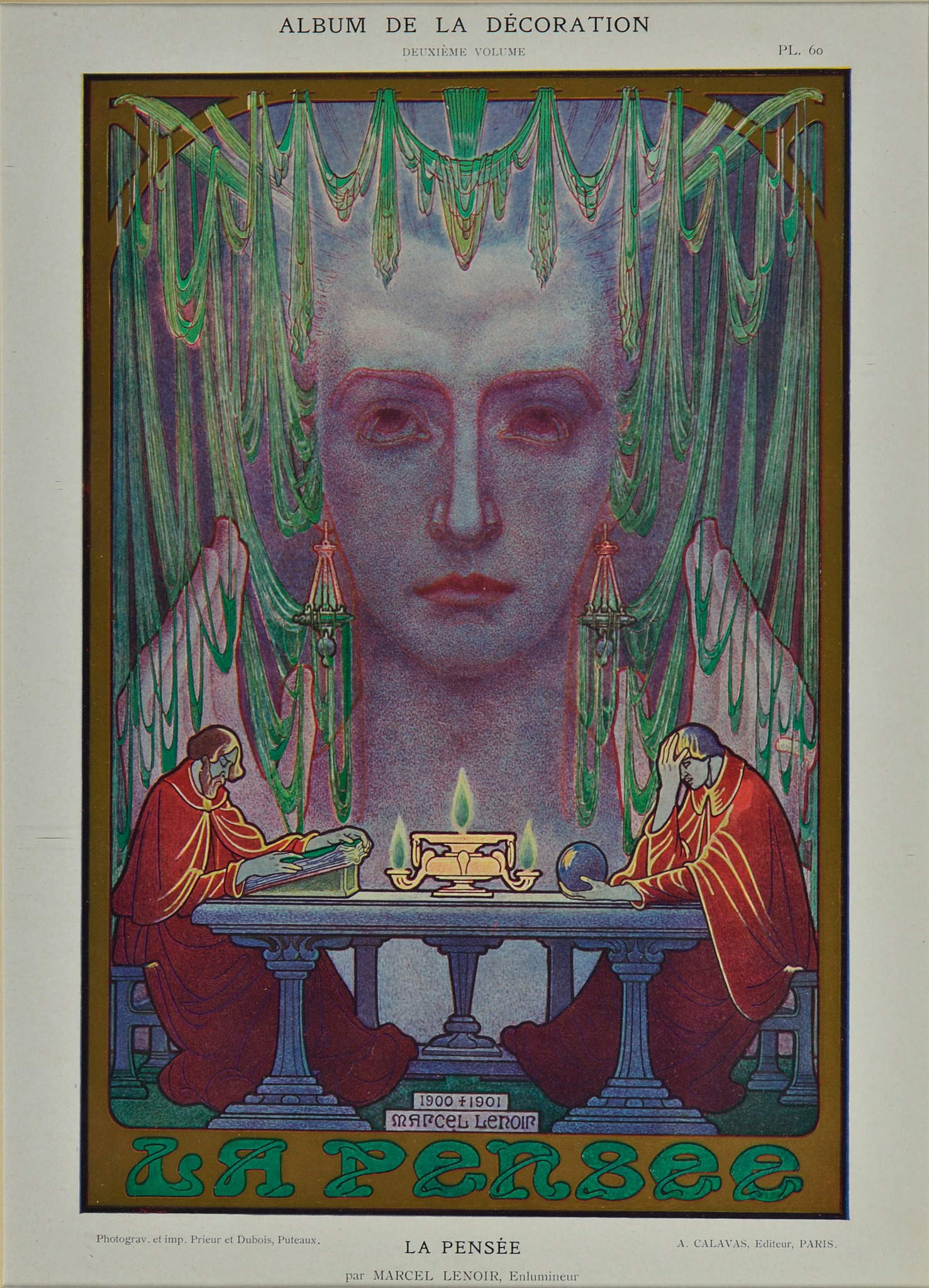

Toward the end of the exhibition that Collesalvetti’s Pinacoteca Comunale “Carlo Servolini” is dedicating, until Oct. 2, 2025, to Aleardo Kutufà, a singular, versatile genius who has fallen into oblivion, appears awork, a chromotype by Marcel-Lenoir, the pseudonym by which the French symbolist Jules Oury called himself, which depicts the apparition of a hieratic and spectral woman, evoked by two wise men meditating, seated in front of a table, by the light of a lamp. It is entitled La pensée and by itself could almost be enough to give an idea of the interests of Kutufà, who was a poet, art critic and artist himself, “an exceptional personality,” says Francesca Cagianelli (who together with Stefano Andres and Emanuele Bardazzi curated the exhibition), “among the ranks of that urban spiritualist circuit, traversed as much by the Divisionist experiments coordinated by Benvenuto Benvenuti under the direction of Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, as by the esoteric reflections of the Belgian Charles Doudelet, the leader of international Symbolism.” Marcel-Lenoir’s work, a chromotype of which is presented in the exhibition, evokes the same, long title of the exhibition, The Hour of the Lamps. Dialogues of Aleardo Kutufà between D’Annunzio aestheticism, crepuscular ghosts and the dream of the Middle Ages. A title that contains everything. The nocturnal atmosphere, first of all: a trait that Kutufà shares with the artists who preceded him in the exhibitions of the Collesalvetti Municipal Art Gallery: Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, Serafino Macchiati, Gino Romiti, Doudelet himself, in other words, primates of that Symbolist milieu that conditioned Tuscan (and not only Tuscan) culture of the early 20th century. The hour of twilight is for the D’Annunzio of Leda without the swan “the hour of the domestic lamps”: “with every lamp lit, my melancholy overflowed as if to feed it.” It is the hour when the servant governs the lamps “and lights them in the earthly chamber and they seem to be already present for something divine so that they may be preceded in the already dark staircase but nevertheless let us know in the delay those even divine thoughts which accompany the parting of the other light from each of our friendly things to return to the West.” Expression later taken up by journalist Francesco Casnati who would use it for one of his articles on D’Annunzio’s Notturno (“L’ora delle lampade: About D’Annunzio’s Notturno,” published in 1922 in the journal Vita e pensiero), centered on those “shadow explorations,” Casnati himself had said them, that had sustained the darker D’Annunzio and are reflected in Kutufà’s work.

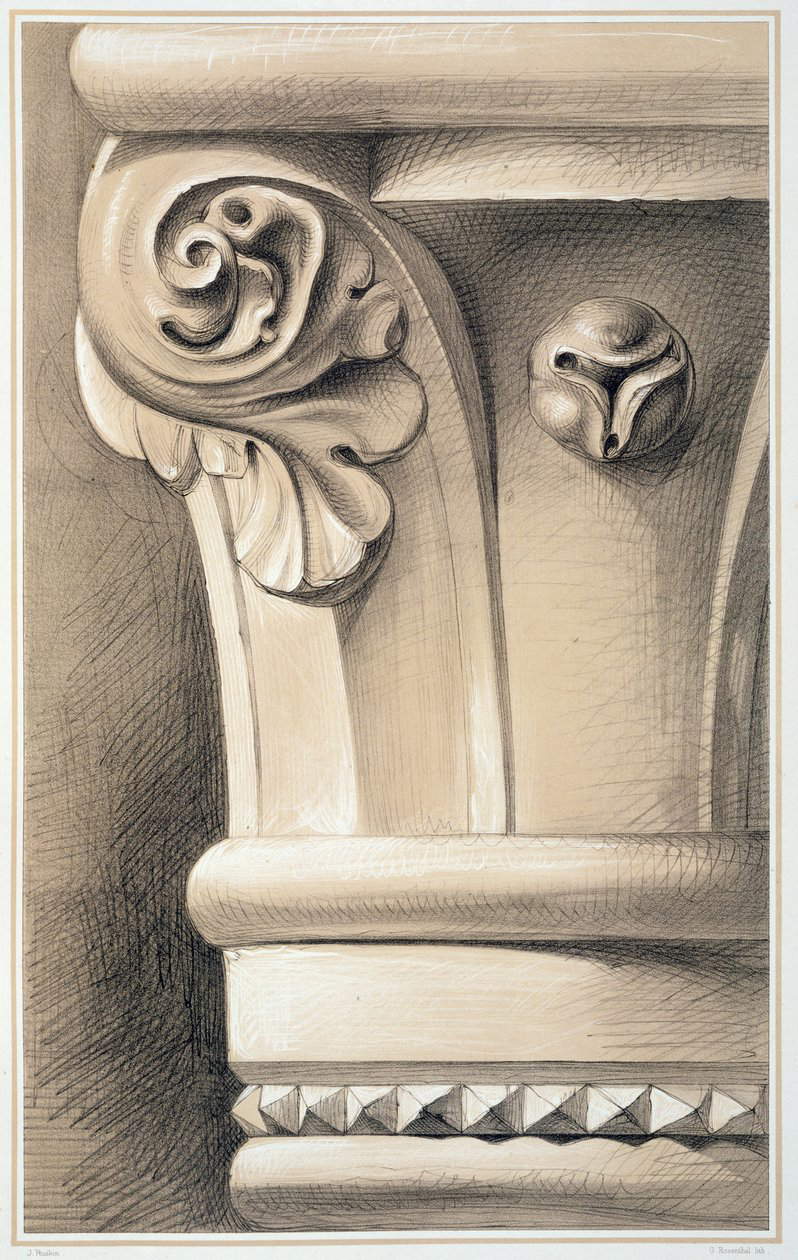

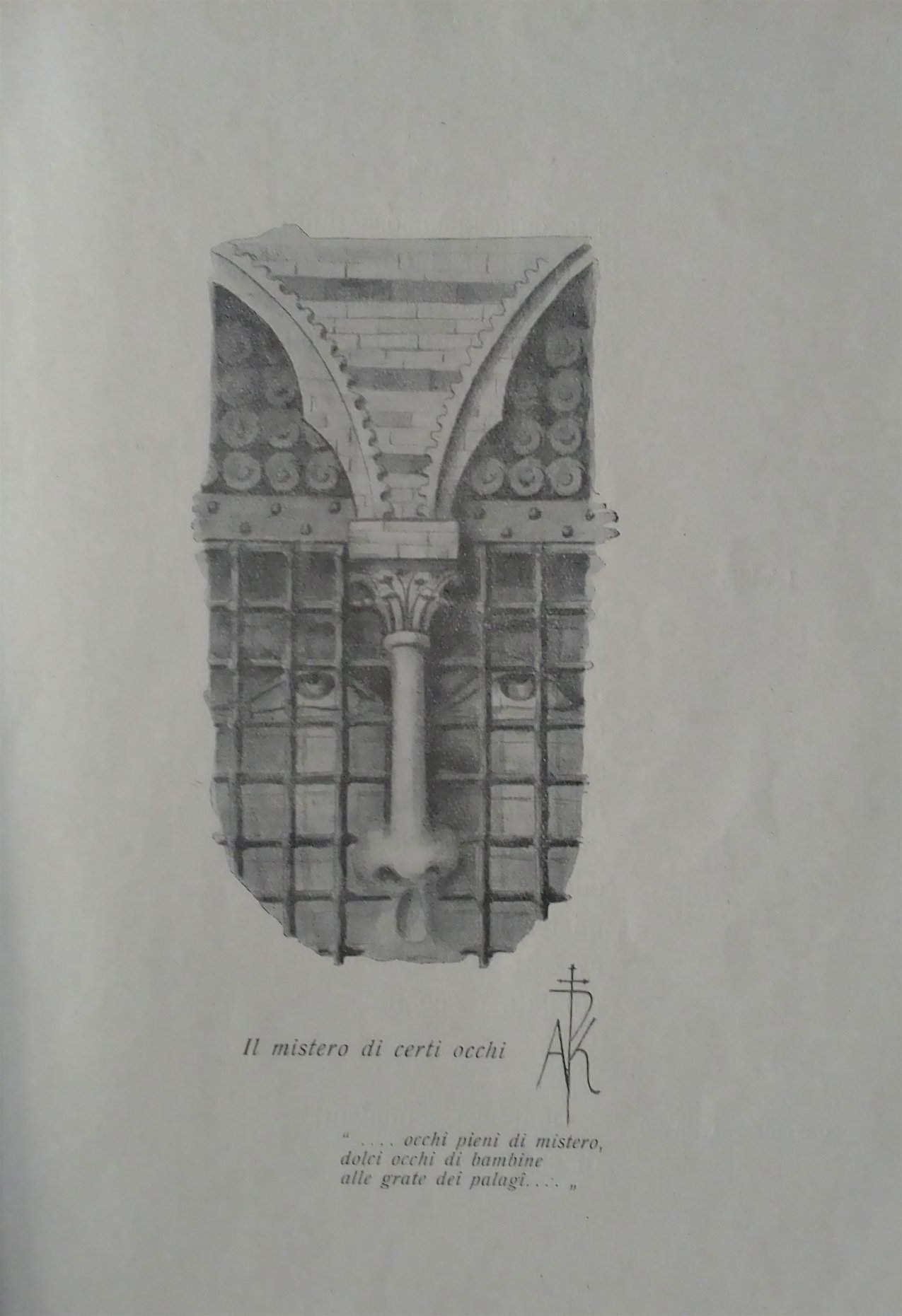

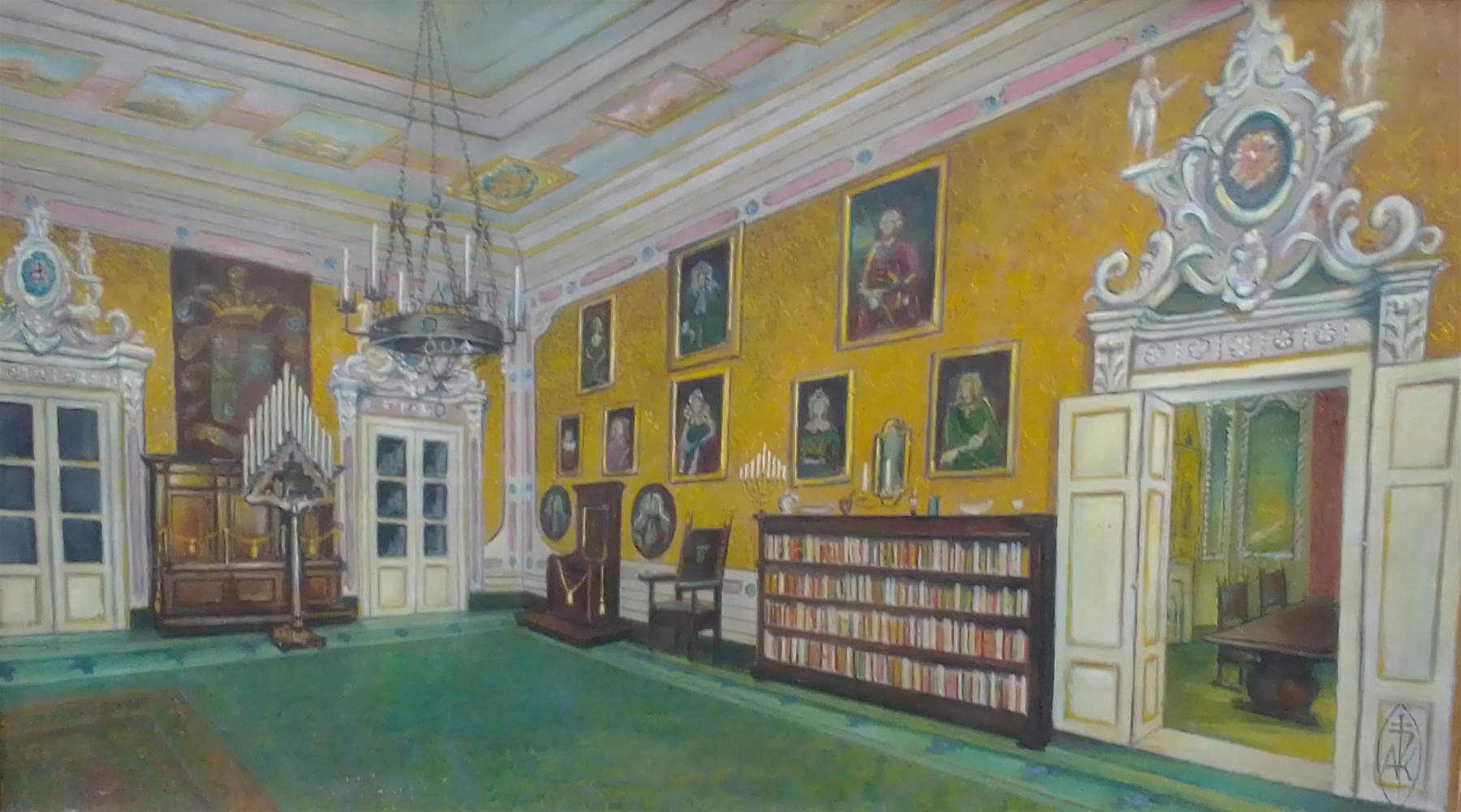

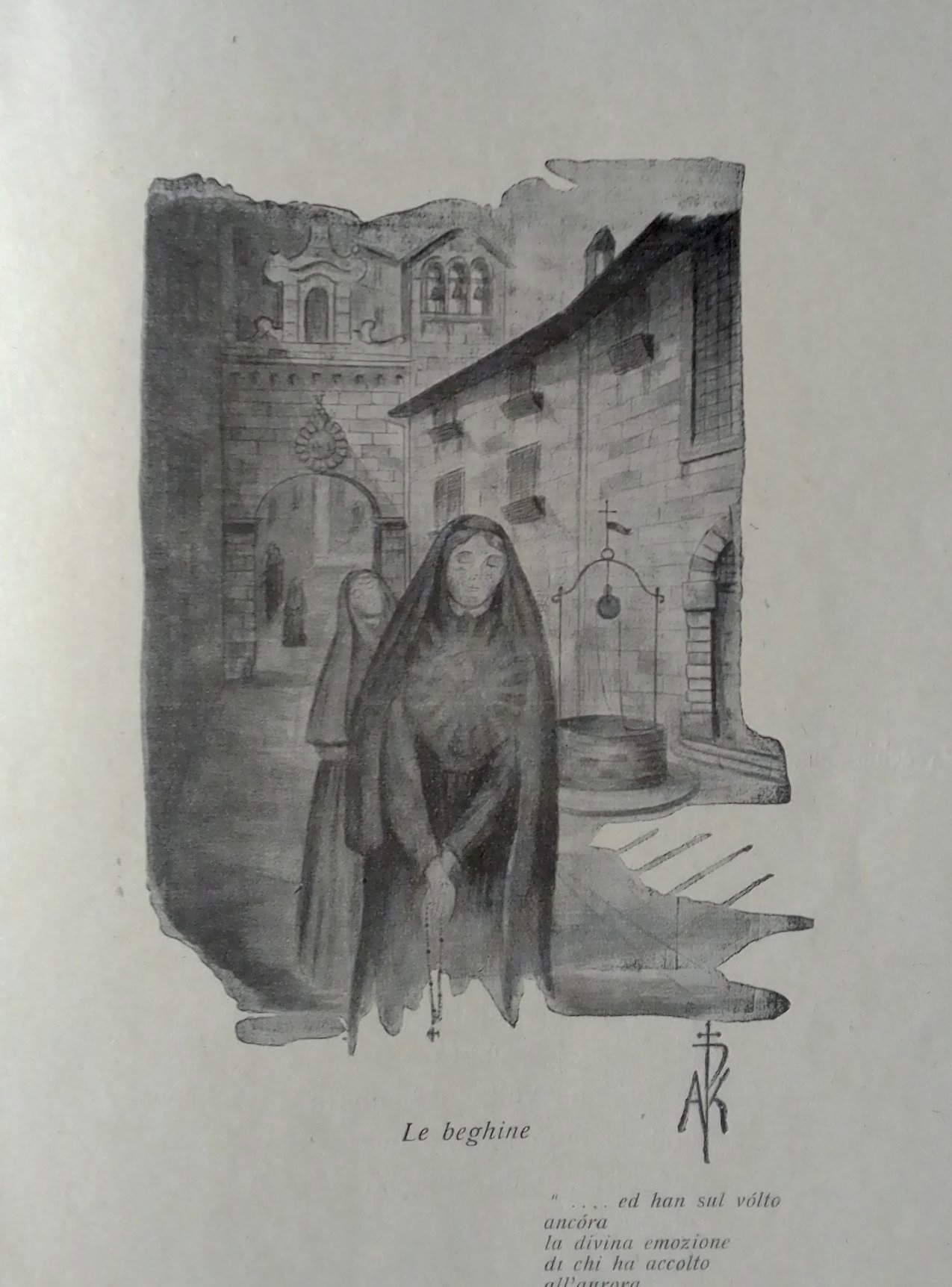

On the other hand, the other part of the title, “Dream of the Middle Ages,” indicates the Ruskinian fervor that kindled the young Kutufà’s soul, so much so that the review opens exactly in the sign of John Ruskin, evoked first and foremost by the presence of Gino Mazzanti’sÀkanthos by Gino Mazzanti, also a painter and art critic, who had published two volumes, one about painting (untraceable to this day) and, precisely, this Àkanthos which is a breviary of architecture imbued with Ruskin’s culture and which marks perhaps one of the peaks of Ruskin’s fortune in Italy. Fortuna, moreover, decidedly scarce, and therefore a rather rare exemplum , accompanied in the exhibition by a pair of lithographs by Ruskin himself (the capital of a Venetian palace and one of St. Mark’s basilica), by another lithograph, by Charles Doudelet, demonstrating how this fairy-tale imagery was a source of common cues for many Symbolists, as well as by an unpublished Triptych in which Kutufà depicted the interior of his palace in Livorno (the artist was from a noble and wealthy family of Greek descent), filled with works ofart and set up according to a vision marked by a syncretism that held together neo-Gothic glimmers, esotericism and oriental suggestions, and by some illustrations that Kutufà executed for theElegy of the Dead Cities published in Livorno in 1928. In this work, writes Emanuele Bardazzi, Kutufà "offered a poetic summation of all those commonplaces and exempla of mournful sensibilism that in Italy had enchanted sad souls at the dawn of the twentieth century, between D’Annunzio influences and decadent literature from beyond the Alps."

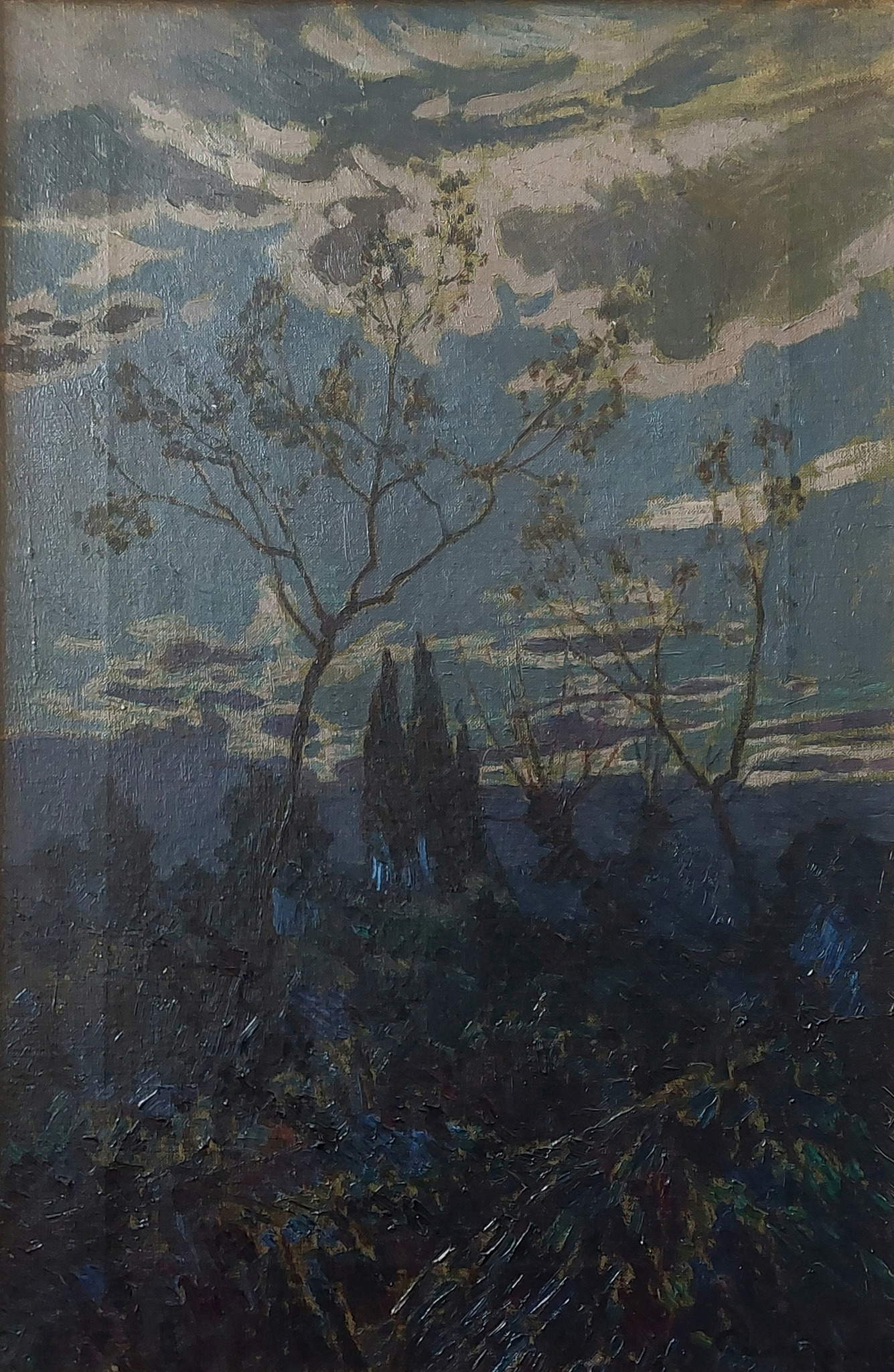

The continuation of the exhibition, especially in the second and third sections, aims to document precisely this “crepuscular melancholy of Kutufà,” as Bardazzi calls it, by exploring some trajectories of early 20th century Tuscan symbolism that were particularly congenial to Kutufà: his volume Benvenuto Benvenuti. A Colloquium of Aleardo Kutufà d’Atene, reprinted on the occasion of the exhibition in a new edition preceded by essays by the three curators, provided the argumentative basis for reconstructing his poetic imagery nourished with almost mystical mystery, given also his idea of criticism, which for him had to be “profound signification of the mystery of a soul manifested through the plot of the works of the battles of everyday passions.” A concept of criticism deeply related to the ideas of Angelo Conti’s Beata riva , for whom the critic was like the conscience of the artist (it was Kutufa himself who had admitted his ancestry), and by the Athenian summarized in the formula for which criticism is “the art of enjoying art,” and the critic’s task can only be that of “feeling the beauty of an artistic work and expressing its emotion with the musical and ideal resources of the verb.” The second section of the exhibition is therefore dedicated to that epic-panic reinterpretation of the Symbolist landscape that was dear to Kutufà and that moves among landscapes at twilight (Gino Romiti’s Evening , Eugenio Caprini’s Landscape ), among those stone poems, those remote epochs that dot the region’s villages (Carlo Servolini’s Fountain , Gabriello Gabrielli’s Cemetery , theAntico borgo of Lorenzo Cecchi, and especially the many views of Benvenuto Benvenuti, the artist with whom perhaps Kutufà was most in tune), and even among transfigured and ghostly visions (those of Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona).

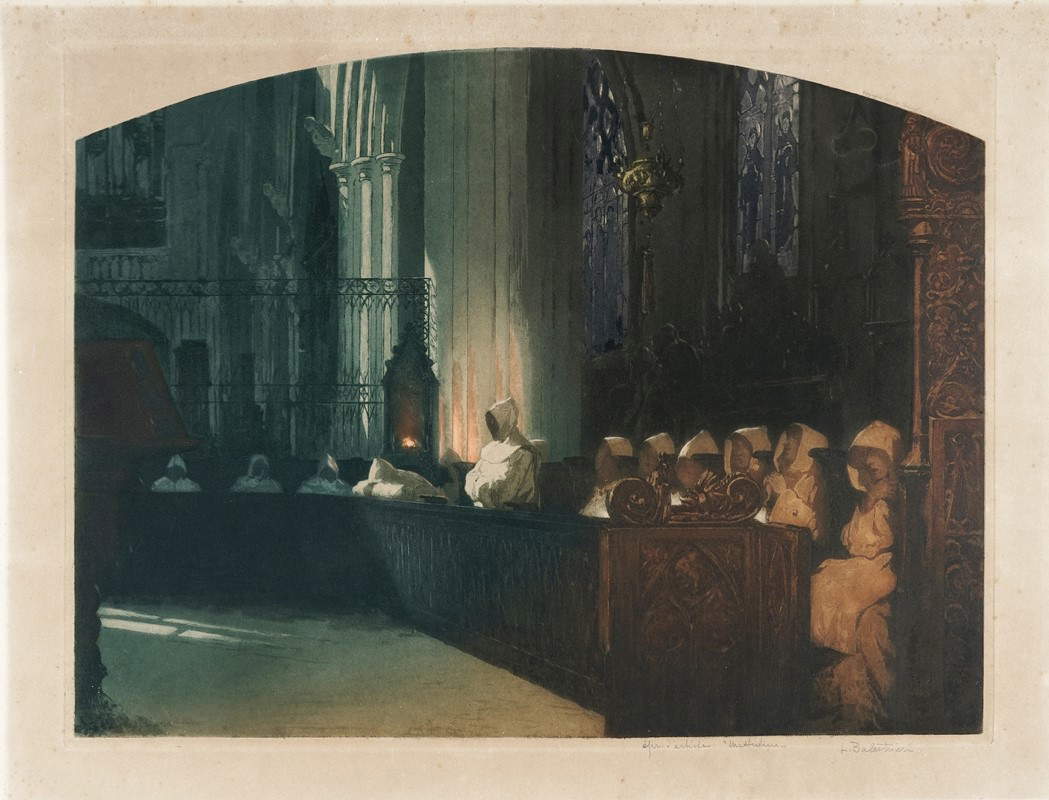

Then there is a Kutufà of a more urban scope, which is the one investigated by the third section (entitled Gli Uffizi del Vespro. Cities of Enchantment and Dream, with quotation from theElegy of the Dead Cities), where the nocturnes of the artists Kutufà frequented converse with visions of Rodenbach’s dark, gloomy and spectral Bruges evoked by some engravings such as Adolphe Dauvergne’s Petits Nocturnes de Bruges , Georges de Feure’s Lecture , Ferenzona’s Bruges , theEntrée du beguinage by Mélanie Germaine Tailleur, and also Kutufà’s own Beghine , an illustration he executed for theElegy of the Dead Cities. Interesting is the recovery of some forgotten female voices: Città di sogno, a 1926 woodcut by Irma Pavone Grotta, Ferenzona’s pupil, is to be counted among the most visionary transfigurations of the exhibition itinerary, and Bona Ceccherelli’s Notturno is a witness to a Nordic imagery that in the early twentieth century fascinated the entire Tuscan Symbolist milieu. The closing of this short but dense itinerary of the visit knots up at the beginning and, again sounding out the Belgian Symbolist strand (Doudelet’s etchings abound, again, those of Fernand Khnopff, while the end of the itinerary is reserved precisely for the Penséand Marcel-Lenoir’s), he returns to the fantastic and mystical Middle Ages that eventually overflow into Italy and give rise to singular admixtures (for example, the charcoal on paper Ella si va sentendosi laudare by Romolo Romani prey to Dantean reminiscences, or the mouthy drypoint Un peccato by Ferenzona) and even to accesses of spirituality more popular (the usual Ferenzona’s nuns, Lionello Balestrieri’s church interior).

The first merit of the exhibition at the Pinacoteca Comunale is that of having rescued Aleardo Kutufà from oblivion and thus having sketched with supreme profusion the contours of a highly original voice of our early twentieth century, whose forgetfulness can be explained, in some ways, by the alternating fortunes that twentieth-century critics reserved for Symbolism as a whole: this has resulted in a historiographical delay that has begun to be filled only in recent times, and the Collesalvetti exhibitions have placed themselves at the head of a slow but constant operation of research on an entire theory of artists, writers and critics who have shaped a certainly not secondary part of Italian culture at the beginning of the 20th century. Talking about Symbolism, today, is still not the same as talking about Futurism, to mention a movement that has known, albeit for different (indeed: opposite) reasons, an identical oblivion in the second half of the twentieth century, but also thanks to exhibitions such as the one on Kutufà the conditions can be created for a full and complete review of inveterate historiographical clichés . On the penalization of Kutufà, then, also intervened more “local” elements, so to speak, those same elements that marginalized, for example, artists such as Ferenzona, Gabrielli, Pieri Nerli and many others, that is, the defeat of “that ’D’Annunzian aestheticism and that syncretistic taste,” to use the words of Francesca Cagianelli, decreed by the circles of Leghorn painting more inclined to go along with the dominant “post-macchiaiolo” verb, to use an adjective that is dated but has the merit of being easily understandable.

The exhibition then reconstructed in detail Kutufà’s biography, dispelling even doubts that his was a nom de plume: in the reprint of Colloquio, Stefano Andres offers a lively fresco of Kutufà’s life, born in Livorno in 1891 to Nicola and the Pisan noblewoman Gemma Turini del Punta, a sincere lover of philosophy and history of religions, self-taught, close to the thought of Angelo Conti, Nietzsche, Stirner, Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard, with a ’melancholic and nostalgic soul, and capable of earning even the praise of Gabriele d’Annunzio, with whom he was in contact for some time, when in 1913 he published his first novel, A sera. A long life, that of Aleardo Kutufà: he passed away in 1972, after an existence of alternating fortunes (in the 1940s, for example, finding himself in precarious economic conditions he was forced to live off of odd jobs that were procured for him by his friend Benvenuti: he would find stability only after the war, teaching in high schools), and without seeing his dream of seeing his complete works published crowned, so much so that, after his death, several unpublished works ended up scattered.

To think that, already in his lifetime, in 1960, when Commedia Labronica delle Belle Arti, a satirical poem by Carlo Servolini published posthumously, was being printed, Kutufà was already included in the “Parade of the Forgotten,” despite the fact that in the years of his first production, praise for him came from all quarters. The Collesalvetti exhibition thus has the merit of advancing our knowledge of Italian symbolism by bringing this eclectic visionary out of oblivion and, above all, having highlighted his merits: the popularization of Ruskini’s word in Italy, his liaison with Belgian symbolism, the reinterpretation of Benvenuti’s architecture in the light of D’Annunzio’s Laudi and on the basis of a critical approach that took its cue from that of Angelo Conti, the versatility of an intellect that contributed to warming the cultural climate of Tuscany at the beginning of the 20th century with results of heated originality. A searching exhibition, not the easiest, certainly, but one that is anything but condescending, and that is a merit.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.