If there is one thing Anselm Kiefer is not afraid of, it is confrontation with the past: whether it is his personal experience or the installation of works in historically highly connoted contexts, the artist always manages to trigger short circuits of great effectiveness and power. This was demonstrated by the grandiose project through which in 2022 (thanks to the courageous invitation of Gabriella Belli, then director of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia) he was able to cover the walls of the Sala dello Scrutinio in the Doge’s Palace in Venice, where the artist temporarily superimposed over paintings by Tintoretto, Palma il Giovane, and Andrea Vicentino, huge canvases that reinterpreted the celebration of the glory of the Serenissima in a contemporary language. Kiefer, celebrated by many as the greatest living artist, was then summoned to Italy in 2024 for a full-bodied retrospective hosted in the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, and today it is Milan’s turn to devote an exhibition to him that has raised high expectations since its announcement. The location, like the Venetian one, is decidedly evocative and rich in traces of the past: the Sala delle Cariatidi in Palazzo Reale, in fact, dates back to 1774-1778 and was designed by Giuseppe Piermarini; on August 15, 1943, during the attack on Milan by RAF bombers, an incendiary fragment fell on the roof of the room, causing it to catch fire. Thus were destroyed the vault (including Francesco Hayez’s fresco of TheApotheosis of Ferdinand I from 1838) and the gallery with paintings by Andrea Appiani, as well as most of the stucco decorations and the floor.

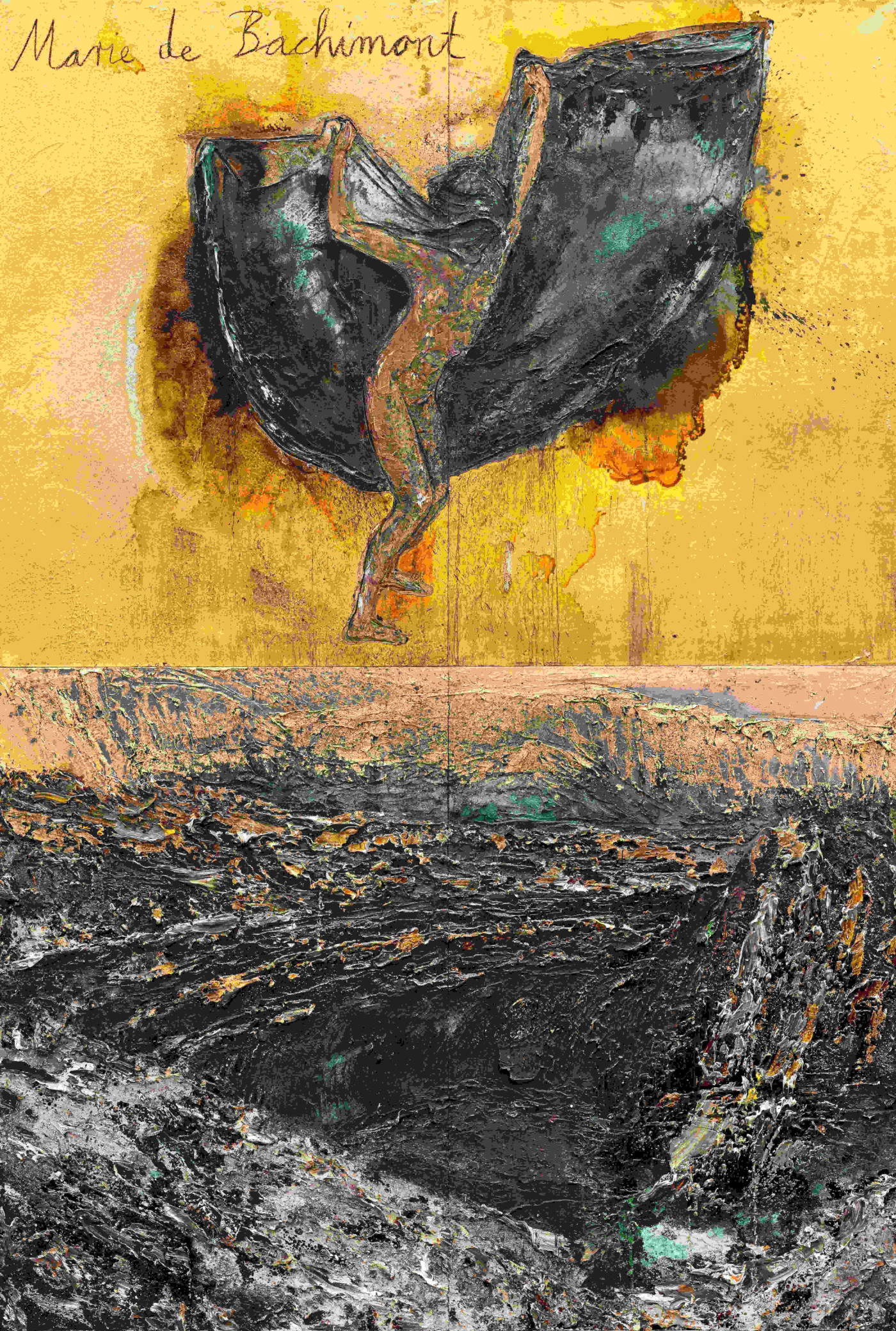

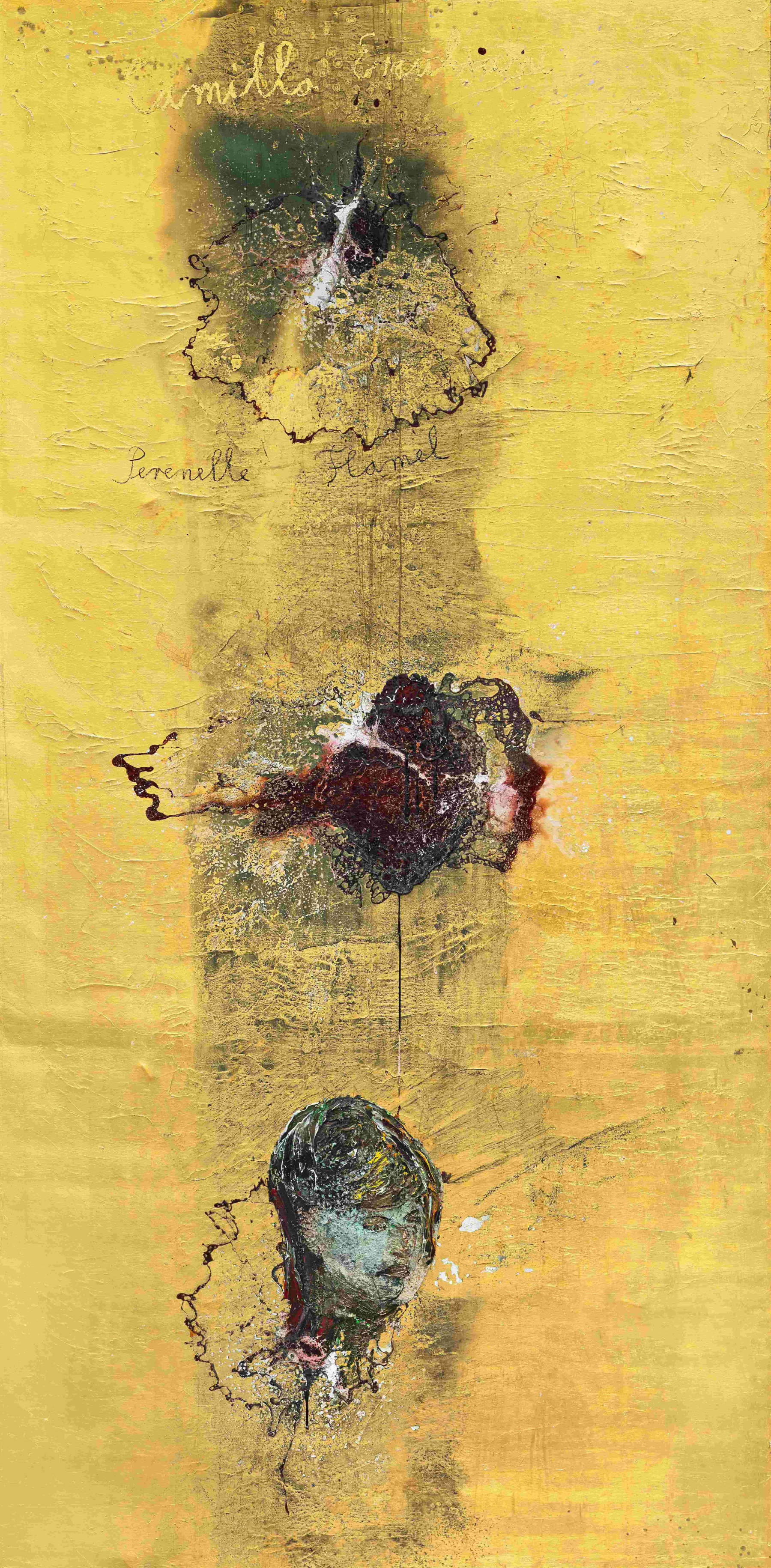

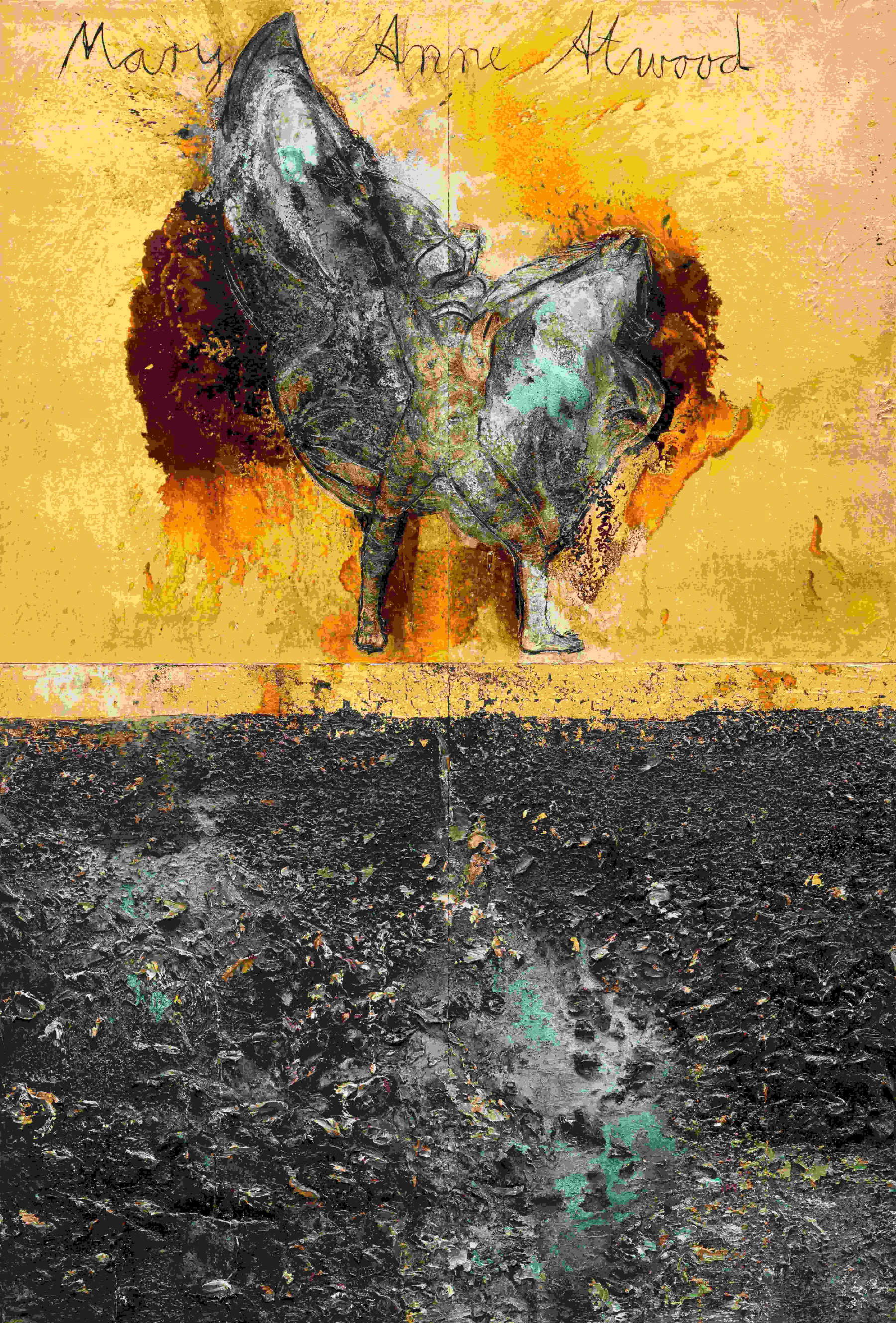

The artist himself admitted his fascination with that imperfect environment, pervaded with a decadent atmosphere typical of “ruins” and adorned with torn and never reconstructed sculptures, as well as oxidized mirrors that give rise to interesting reflection effects. During the press conference, Kiefer also revealed that the original plan was to hang the paintings overhead, and we believe that doing so would have made the effect even more dramatic than the current exhibition set-up, which sees the canvases mounted on supports that resemble screens. In the center of the room, therefore, corridors are formed in which one wanders around to observe the works from very close up, which also involves a certain amount of neck strain in order to catch a glimpse of the upper part of the paintings, which reach the considerable height of almost six meters: the impression is that these imposing screens make one lose a bit of the close connection with the original decorations of the room, particularly the caryatids. If we are allowed a criticism, we express it towards the casters at the base of the supports, decidedly “out of tune” in such a prestigious context; all the more so since the eight paintings placed in the Hall of the Skylight are mounted on invisible supports and resting directly on the floor, with a more elegant effect.

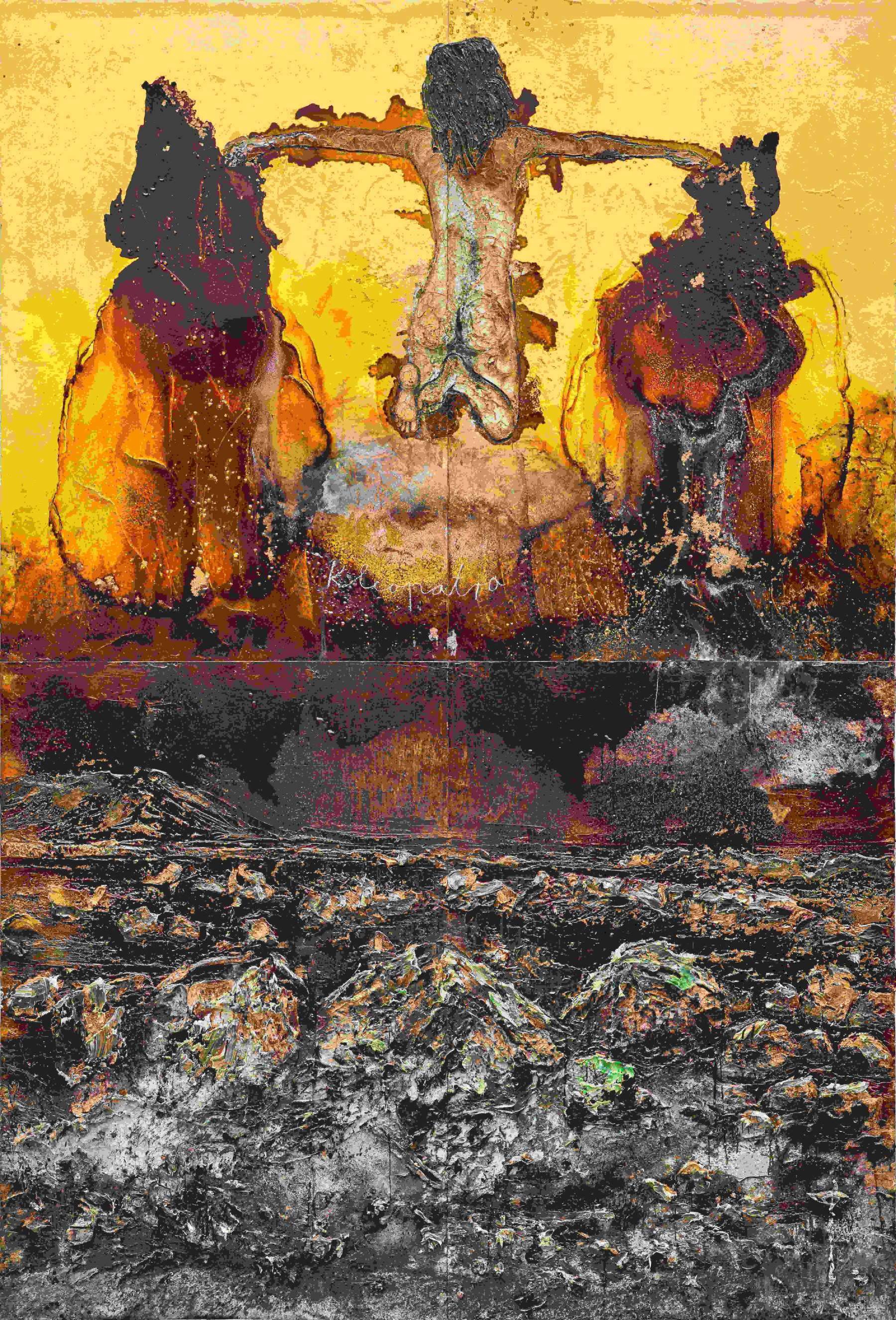

But let us come to the protagonists of the forty-two canvases: Kiefer focused on the women who over the centuries studied or practiced alchemy and in this way contributed to the birth of modern science, only to be forgotten by history and to re-emerge recently thanks to numerous researches, such as that of Meredith K. Ray(Daughters of Alchemy. Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy, Rome, 2022). This is not the first time the German artist has dealt with alchemical themes: already in the 1980s he was inspired by the “saturnine melancholy” (impossible not to call to mind the famous engraving by Albrecht Dürer) by producing a series of works in which he made extensive use of lead, the metal representative of the first alchemical stage, linked to Saturn and the “nigredo,” or putrefaction that forces one to “make a choice amidst the great reservoir of possibilities,” the artist wrote in a 2011 text. In Melancholia of 1990-1991, moreover, the polyhedron of Dürerian memory is evident, and the title itself corresponds to that of the Renaissance artist’s masterpiece.

The techniques employed by the artist can also certainly be juxtaposed to alchemy, as the philosopher and historian of science Natacha Fabbri points out in the catalog essay: “The chromatic rendering itself is the result of living processes: oxidation, patinas, combustion, electrolysis, sediment, slow chemistry that continues to write on the support and shape it.” The result is a highly recognizable stylistic figure, which tends more toward the transmutation of matter than toward an unchanging result over time, from which, among other things, a distinctive sensory effect follows: before the gaze, Kiefer’s works can in fact be recognized by the sense of smell, perceiving their unique odor, characterized by pronounced chemical notes, of processes still in progress. A smell that is also distinctly perceived in Milan as soon as you enter the Sala delle Cariatidi.

The series made for Palazzo Reale has a strong feminine connotation, although it is not a “feminist” project, Kiefer is at pains to reiterate, who, during the Milan presentation and on other occasions, declared that he is “half-woman,” thus nullifying any gender discourse. In fact, The Alchemists stands among his other series dedicated to women, such as Frauen der Revolution, Women of Antiquity, Reines de France, and works dedicated to Lilith, all of which were recalled by curator Gabriella Belli. What then are the hitherto almost unknown subjects of the procession of painted women, advancing observed by the remains of other female creatures, the caryatids, molded in stucco and torn by the violence of war? These alchemists were also queens and noblewomen, wives of philosophers and men of science, autonomous scholars of alchemical theories and courageous practitioners in domestic workshops, or even simple assistants to fathers and husbands who devoted themselves to the search for the “philosopher’s stone.” Many of them published treatises on alchemy, botanical repertories, collections of recipes for medicines and cosmetics, often driven by charitable and social intent; of others, memories are preserved in texts by various authors or in posthumous publications. Each protagonist, in Kiefer’s series, is identifiable by his or her name traced in gold lettering and sometimes by symbols that are also recurring ones in the artist’s poetics: the lead book, the sunflower with its head lowered, dried flowers and plant elements as well as, of course, the gold that illuminates many backgrounds against which some figures in flight, surrounded by a fluttering cloak, stand out. A pattern, this, that we had already seen in the guiding work of the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition, Engelssturz(Fall of the Angel).

Thanks in part to the biographies summarized in the catalog, we thus discover that alchemists have existed since ancient times, and the German artist today restores their existence, their practices, their thoughts and visions, as well as their courage. Among the most intriguing figures, whose faces and bodies emerge from the shifting material covering the canvases, are Theosebia and Paphnutia: the former was a colleague or pupil of Zosimus of Panopolis, an alchemist who lived in the late third and early fourth centuries CE, while the latter was considered by Zosimus an example not to be followed. In ancient times Cleopatra was also active in Alexandria, while at the height of the Middle Ages Queen Blanche von Navarre of France patronized the alchemist Nicolas Flamel. Accounts about alchemists in the fifteenth and especially in the sixteenth century are more numerous, and prominent among them are Caterina Sforza, lady of Imola and countess of Forli, author of the manuscript Experimenti in which she collected 400 recipes for cosmetics and pharmacopoeia, as well as procedures for operative alchemy; Anne Marie Ziegler who promised, thanks to an oil called “lion’s blood,” that she could generate life and who, having failed to create the philosopher’s stone, died at the stake in 1575; Sophie Brahe, sister of the astronomer Tycho Brahe, who practiced chemistry and medicine and cultivated a garden of the simple to derive remedies for the least of these. The timeline of alchemists then includes Anne Conway, linked to philosopher Henry More and an interpreter of alchemy as an experimental art in the service of healing; Dorothea Juliana Wallich who managed to publish numerous chemical texts, while Elisabeth Grey’s posthumously published volume contained both alchemical solutions and a culinary cookbook. Marie Meudrac’s book, La Chymie charitable et facile, en faveur des dames published in 1666, on the other hand, had considerable fortune due to its systematic but accessible slant, aimed specifically at a female audience. And then, for the 18th century, we recall Susanna von Klettenberg, Goethe’s spiritual guide, whom he involved in his experiments in a makeshift home laboratory, introducing the famous writer as well to Hermeticism. Among more recent alchemists, a key figure in the spiritual reception of alchemy in nineteenth-century England was Mary Anne Atwood, who published a work with her father only to withdraw and destroy it in the belief that she had revealed the secrets of a sacred matter.

Anselm Kiefer is certainly not the first artist, nor will he be the last, to be inspired by alchemical processes: Lawrence M. Principe in his catalog essay cites David Teniers, Pieter Brueghel, Thomas Wick, for example. We add the inescapable and already mentioned Albrecht Dürer with his Melancholia I, rich in hermetic symbols and exquisitely studied by Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, and then Parmigianino, whom Vasari called a “man of salvation”, telling, moreover, that the painter was ruined by his incessant search for gold; after the disappearance of Francesco Mazzola there was even gossip about his lethal mercury poisoning (likely, however, he died of malaria).

As is obvious, those interested in alchemy were not, and are not, only artists: indeed, one cannot forget Carl Gustav Jung and his volume Psychology and Alchemy (1944), written after 15 years of study and capable of rereading alchemy, precisely, as a metaphor for self-realization and exploration of the unconscious. We mention it also because, to coincide with the opening of the Milan exhibition, psychoanalyst Massimo Recalcati published for Marsilio (whose business unit Marsilio Arte co-produced the exhibition Le alchimiste together with Palazzo Reale) Il seme santo. The Poetics of Anselm Kiefer, setting out to answer the questions, “Is it possible to generate something alive from what already appears dead? Is it possible to make from the remains a new work?” Even today, then, the alchemical stages of nigredo,albedo, and rubedo prove relevant and capable of not only telling the roots of modern science, but also of symbolically sublimating archetypal questions of existence and spirituality.

The author of this article: Marta Santacatterina

Marta Santacatterina (Schio, 1974, vive e lavora a Parma) ha conseguito nel 2007 il Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dell’Arte, con indirizzo medievale, all’Università di Parma. È iscritta all’Ordine dei giornalisti dal 2016 e attualmente collabora con diverse riviste specializzate in arte e cultura, privilegiando le epoche antica e moderna. Ha svolto e svolge ancora incarichi di coordinamento per diversi magazine e si occupa inoltre di approfondimenti e inchieste relativi alle tematiche del food e della sostenibilità.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.