To crown Nan Goldin’s more than 40-year career, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, in collaboration with the Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and the Grand Palais Rmn in Paris, has organized an extensive traveling retrospective devoted to her work, entitled This Will Not End Well, the Milan leg of which is currently underway, which we visited. Nan Goldin (Nancy Goldin; Washington, D.C., 1953) is one of the most influential artists of our time: her work has revolutionized the role of photography in contemporary art by addressing crucial themes of identity, love, sexuality, addiction and vulnerability with an unfiltered approach characterized by an absolute convergence of art and life. His documentary practice, steeped in autobiographical references, ushers in a new genre, which we might call a “public visual diary,” and a new aesthetic, generated by a highly personal combination of descriptive sensibility and fascination with excess. The most significant body of her work chronicles her life and that of her friends in the New York underground scene of the late 1970s and early 1990s in shots that challenge conventional notions of beauty, privacy, and intimacy by combining direct capture and introspection.

The last of four children of a Jewish family, Goldin spent her childhood between the suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland, and Lexington, Massachusetts. At the age of fifteen, already scarred by the trauma of her older sister’s suicide and a conflicted relationship with her family, she moved to a commune and attended Satya Community School in Lincoln, Massachusetts, an educational institution known for its unconventional methods and the freedom it allowed students, where she began photographing in Polaroid. Shortly thereafter, he purchased his first professional camera and began experimenting with black-and-white film, personally developing in the darkroom with classmate David Armstrong, who would become best known for his intimate black-and-white portraits as part of the so-called “Boston School.” The two, who became friends after meeting in a supermarket while they were both busy stealing steaks, assiduously frequented movie theaters to watch films by Douglas Sirk, Michelangelo Antonioni, Robbe-Grillet, Jacques Rivette and Andy Warhol and to admire the Hollywood divas they were obsessed with, such as Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe, an imprinting destined to deeply influence their work to come. It was David who coined the name “Nan” for Nancy, and their respective photographic portraits are the first essays in this genre by both of them. In the early 1970s, Goldin moved to Boston along with a group of drag queens and began documenting their everyday life, which had its nerve center in the nightclub The Other Side. Then the artist, with already to his credit a solo exhibition held in 1973 at Project Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts (an experimental space dedicated to performance and conceptual art), continued his studies at the art school of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and, not having access in the place where he lived to a darkroom to develop and print images, began working with slides, destined to become a distinctive feature of his work. She traveled to London, where she portrayed the youth subcultures of the day, such as punks and skinheads, then in 1978 moved to New York, where she immortalized the frenetic existence she led with friends and lovers in clubs, underground cinemas and in her Bowery apartment.

As she tells it, her images arise not from observation but from her relationships, and the camera, as if it were the natural extension of her arm, becomes as much a part of her existence as talking, eating or having sex. The instant of the shot, rather than implying distance between an observing subject and an object of attention, is for her a moment of clarity and emotional connection, animated by a desire to preserve the meaning of the lives of her loved ones and to restore, through the image, the strength and beauty she sees in them. Goldin’s intent is to show exactly what her world is like, without embellishment or glorification, and her world is a quirky family made up of people bound by a totalizing aspiration for intensity that drives them to force the limits of themselves and relationships at the cost of risking self-destruction. It is in this context that The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, her masterpiece, takes shape, a slideshow composed of color slides, manually inserted by her each time into the projector in a different order, portraying this over-the-top “family” through snapshots in which friends, excesses, love, despair, joy and addiction follow one another. The project for several years is likened to a kind of performance: the first projections (apparently one of these occasions was Frank Zappa’s birthday in 1978) were entirely informal and those attending were, essentially, the same people shown in the photographs.

Closely, it began to circulate in nightclubs and was included in the groundbreaking 1980 Times Square Show in New York, an independent artist-organized collective focusing on themes of urban marginalization, street culture and social identity. In the following years the work acquired a soundtrack and its current title, decided on in 1981 and inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s Ballad of the Pimp (Tango Ballad); in 1985 it was exhibited in New York at the Whitney Biennial, introducing the artist to the institutional context, while in 1986 the celebrated monograph of the same name was published, including a selection of 125 photographs collected from 1979 to the year the book was published. Travels to Asia and Europe followed, where she lived for a decade, staying in Paris, Berlin and London: Goldin, increasingly embedded in the art system that matters (suffice it to say that her main gallery of reference has long been Gagosian), continues to document her swinging life between altered states, detoxes, parties, heartbreaking relationships and peaks of emotional suffering, in total symbiosis with the community of friends by which she is surrounded. The reportages of those years are in many ways searing material and represent a junction of paramount importance in the history of contemporary art. First, of course, because of the situations evoked and plumbed from the most private details: Bohemian apartments, peeling walls, undone beds, public bathrooms, hotel rooms, bar counters, creative outfits, fishnet stockings, heels, makeup sessions, beer cans, alcoholic cocktails, burnt mattresses, nudity, amplexes, parties, spirited or languid eyes piercing the lens, packages of psychotropic drugs, cigarettes, sequins, lines of cocaine, syringes, blood-splattered walls, bruises, queer parades, hallucinated sunrises, heroin ulcers. L

’inseparable mixture of splendor and misery that characterizes each frame restores an indelible impression of the joyous and tragic promiscuity of that unconscious generation before overdoses and the devastating AIDS epidemic decimated its members, imprisoning even the survivors in an impenetrable curtain of shadow. Second, from the point of view of photographic technique, these shots, while flaunting a systematic disregard for the canons of technical correctness through recurrent blurring, unusual cuts, biased viewpoints, flash reflections, under and over exposures, appear to be governed by mysterious internal compositional logics that, however heterodox in appearance, always ensure the balance and harmony of the images. Ultimately subversive is the relationship they establish with the viewer, who has to undergo the paradox of being dragged by an irresistible magnetic force to the heart of an image that cruelly excludes him or her, strikingly subverting the relationship between outcasts and marginalized sanctioned by social norms. Beginning in the 1990s, Goldin expanded his practice by making installations that include moving images, music and narrative voices, and while continuing to photograph his now-mature friends and their children, he turned to activism, founding in 2017 the group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) to fight the drug overdose emergency and supporting the Palestinian cause.

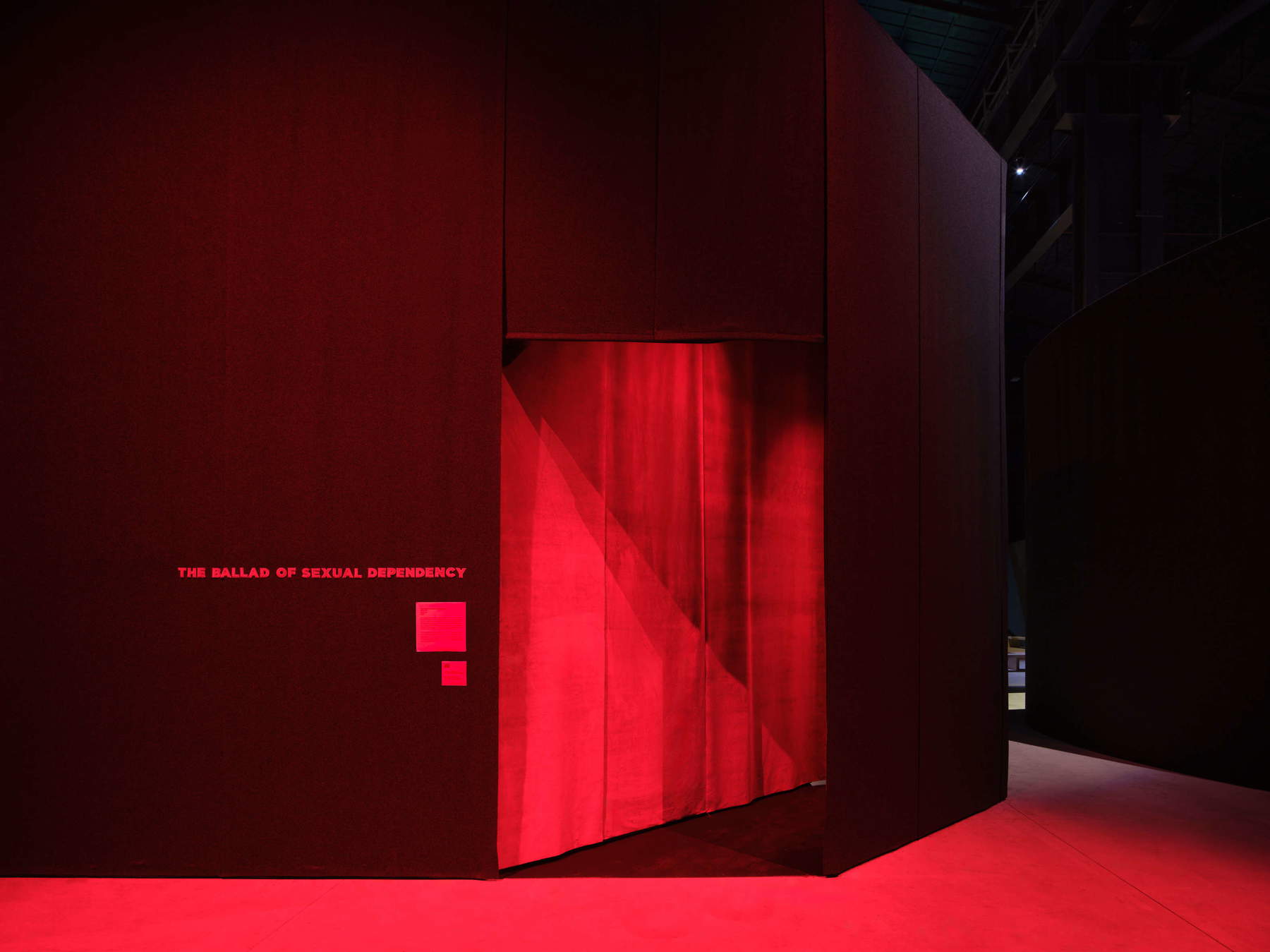

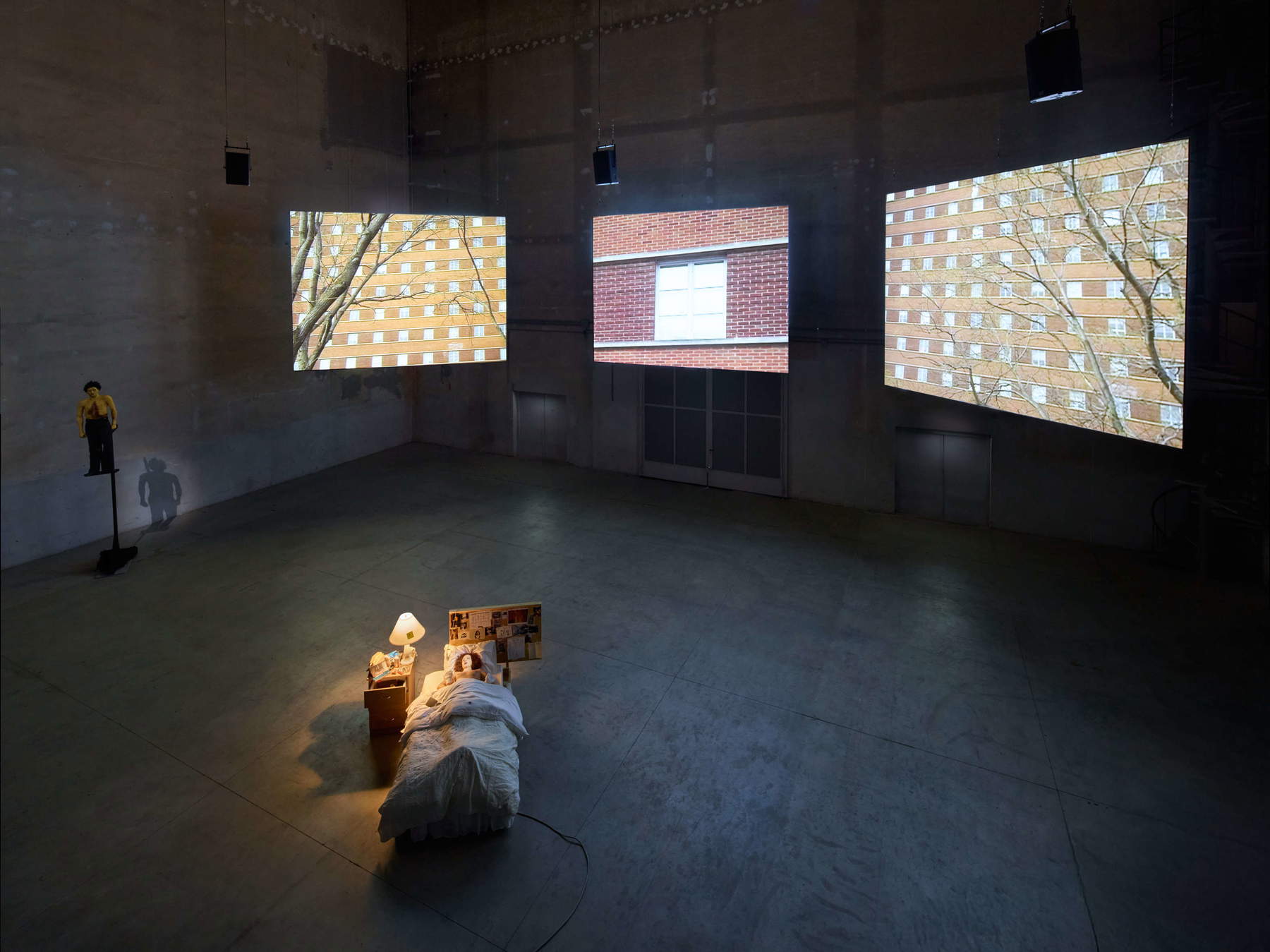

The intent to offer a magnificent exhibition of consecration is apparent from the very entrance to the Pirelli HangarBicocca exhibition: in one of the grand aisles of the former locomotive-building factory, eight different architectural structures, designed by Hala Wardé to compose a metaphysical village of pavilions functioning as “field cinemas,” within each of which a different slideshow is held on a loop. It begins, ça va sans dire, with The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1981-2022), in which for 42 minutes most of Goldin’s most iconic shots, taken in New York, Provincetown, Berlin and London between the 1970s and 1990s, follow one another on a mega-screen. Well in evidence, set into the wall at the back of the room, is the automatic mechanism responsible for the scrolling of the films, whose cadenced shots add up to the soundtrack, composed of a selection of songs that have evolved over time, including I’ll Be Your Mirror (1967) by the Velvet Underground, She Hits Back (1973) by Yoko Ono, Sweetblood Call (1975) by Louisiana Red and Packard (1968) by Edmundo Rivero, which took its final form in 1987. The effect is muscular: the perfect quality of the sound and the magnified view of the images overpower the viewer, in accordance with the self-styled contemporary mantra of immersive experience, which in so many exhibitions seems to be a hypnotizing end rather than a means consubstantial to the work.

It continues, from marquee to marquee, with: Memory Lost (2019-2021), a moving evocation of the dark side of substance addiction accompanied by a sound track alternating between recent interviews with surviving friends and messages recorded in the 1980s from his answering machine; Fire Leap (2010-2022), a sequence devoted to the theme of childhood; The Other Side (1992-2021), a tribute to the transgender community, Stendhal Syndrome (2024), an evolution of an earlier project made for the Louvre in which details of masterpieces of art history preserved in various museums around the world alternate with snapshots from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, revealing how much his altered gaze of his younger years was spontaneously aligned with that of the great masters, and it is this aspect, in this latest work, that is really interesting. It follows: Sirens (2019-2020), a montage of short clips taken from thirty films focusing on the euphoria produced by drug use, included in 2022 in the Venice Biennale selection curated by Cecilia Alemani; You Never Did Anything Wrong (2024), a film shot in Super 8 and 16mm with animal protagonists, set during a magical eclipse, in which the grainy and blurry effects of theimage appear to be an end in themselves, no longer corresponding to the intent of collimating the image with the artist’s “blurred” vision at the moment of the shot as is the case in the photographs of the Golden Age.

Although the exhibition approach taken claims to be based on a desire to indulge Nan Goldin’s oft-repeated cinematic vocation (“I have always wanted to be a filmmaker. My slideshows are films composed of stills”) by focusing on slideshows, the final rendering raises quite a few questions. First of all: given the obvious impossibility of recreating in a museum setting the atmosphere of the underground clubs in which the artist’s sequences were screened at the beginning of his career, is it really appropriate to make up for this distance by relying on state-of-the-art multiplex technical involvement? And again: after pausing in the first pavilion to watch the full screening of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, is it not in danger of being redundant to stand in the other cine-tents where in shorter sequences more or less the same images are repeated, albeit grouped together with different criteria in relation to the theme from time to time announced by the title? Wouldn’t a less spectacular presentation have been more useful if it had flanked the projection of the main work with a reasoned selection of still images so as to leave the visitor the possibility of dwelling on each at will without investing him or her with a massive stream of recurrences? With such an approach, even the inclusion of the most recent works does not seem to play well with the appreciation of this very great artist, highlighting how most of them are based on the reuse of the body of images to which she owes her celebrity within sequences in which new photographs appear that are conceptually subordinate to the intent of relating to the historical ones.

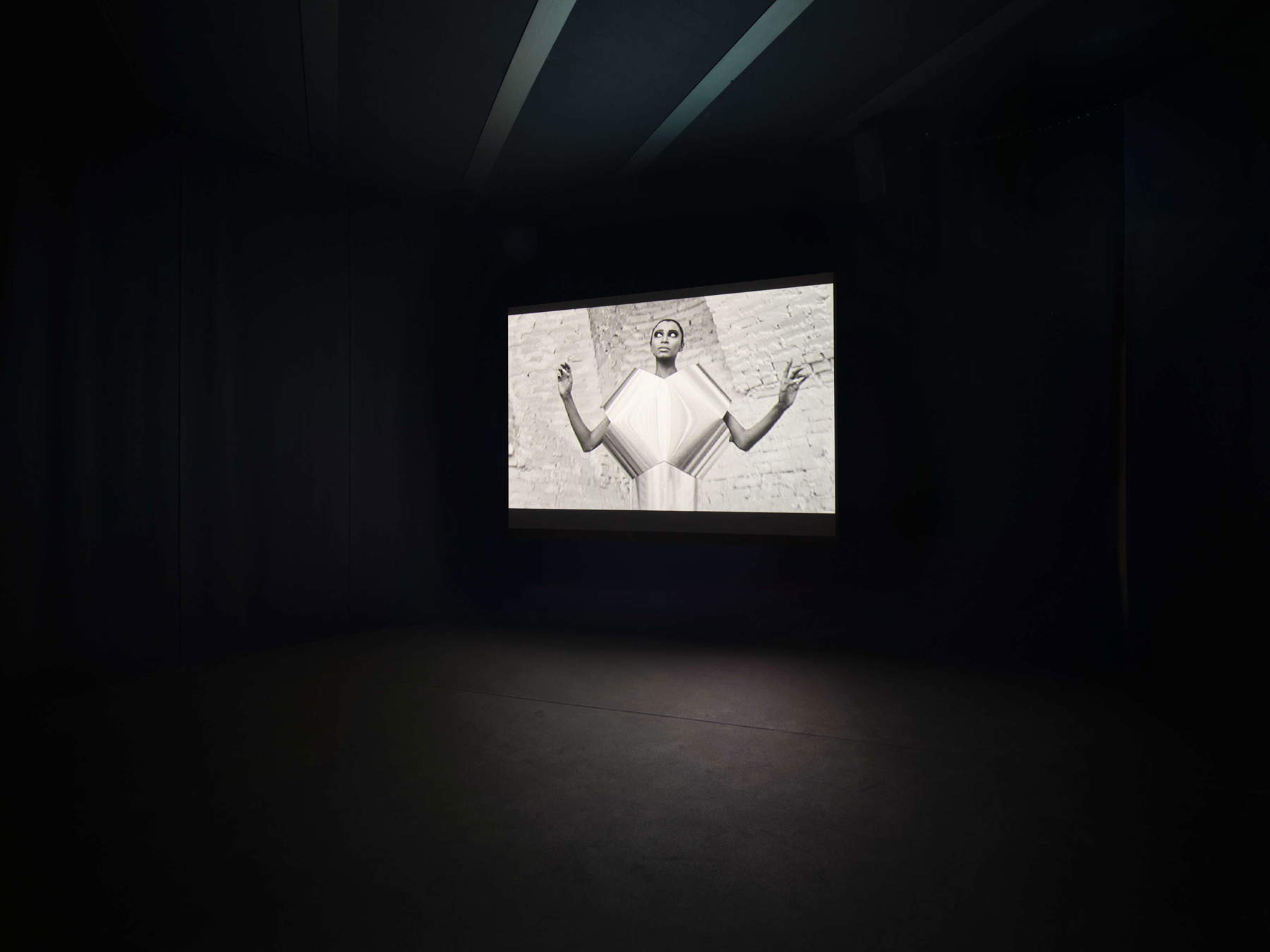

The feeling, growing as one proceeds in the visit, is that the main strength of Nan Goldin’s poetics resided in that total and unrepeatable coincidence between her state of mind, her gaze and a spirit of the time circumscribed to the decades from the 1970s to the 1990s in a precise social context, and that everything that comes after is an emanation of it inevitably weakened from the point of view of the effectiveness of the expressive language adopted. In this regard, even the grandiose installation Sisters, Saints, Sibyls (2004-2022), presented in a way that faithfully replicates the presentation at La Chapelle de la Salpêtrière in Paris, the place for which the work was originally designed in 2004, only confirms this impression. The work consists of three screens in which the visual narrative of the life of her older sister Barbara Holly who died by suicide is articulated, the voice of the artist telling her story, and two sculptures depicting a young woman lying in bed with the connotations of Nan and a man, visible from a raised platform. Despite the massive deployment of means (or perhaps because of it), the installation does somewhat resemble the mega-screens where Bruce Nauman’s most recent Contrapposto Studies were projected on an environmental scale in aextensive retrospective devoted to him in 2021 at Punta della Dogana, which were far less engaging and “necessary” than the historical performances of which they constituted the updated re-edition, visible in the same exhibition through small black-and-white analog monitors. The main reflection provoked by the exhibition at HangarBicocca, therefore, is on the mechanisms of canonization of artists who, at a certain point in their creative career, were able to steer the course of art history, and on how (and whether) they managed to overcome the watershed they themselves generated by keeping their inventive modes current and meaningful without availing themselves of the aura conferred on them by the inescapability of historicized works.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.