Entitled Ottocento svelato. Tales of Collections and Museums in Nineteenth-Century Genoa, the articulated exhibition project that, in Genoa until March 29, 2026, aims to combine scientific research with museographic renewal, restoring centrality to a century often overshadowed by other historical epochs but fundamental to the history of Italian art. The initiative, promoted by the City Council in collaboration with the University of Genoa and the Superintendence, unravels through five exhibitions set up in as many civic venues, involving public institutions, galleries and private collectors in a choral effort aimed at the conscious rediscovery of this period.

The beating heart of this historical reinterpretation is in the Nervi Museums, where the Gallery of Modern Art located in Villa Saluzzo Serra and the Raccolte Frugone in Villa Grimaldi Fassio host two events scurati by Leo Lecci and Francesca Serrati. The exhibitions, titled respectively Artists, Patrons and Collectors in Nineteenth-Century Genoa and The Frugone Collections: a Nineteenth-Century Art Collection for Genoa, offer a multifaceted view of Ligurian collecting. The itinerary set up at the Gallery of Modern Art is structured by themes that investigate the genesis of the city’s collections, the artistic genres favored in the 19th century and the fundamental role played by the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti as a national crossroads. The exhibition boasts more than one hundred works, half of which come from prestigious loans from museums such as the Uffizi in Florence or the Ricci Oddi in Piacenza, while the other half have been recovered from the deposits of the Genoese museum itself, bringing to light treasures that had remained hidden for years and presenting almost unseen pieces owned by the Chamber of Commerce and the Prefecture.

The cultural operation is part of a broader program of rearrangement of museum rooms, designed to integrate well-known masterpieces with rarely seen works, creating a dialogue that reveals Genoa’s pivotal role in the international artistic context of the time. The Raccolte Frugone also participates in this narrative: while maintaining their historical layout substantially unchanged, they temporarily welcome two “guest” masterpieces, works that were exhibited in the city in the second half of the 19th century and now return to dialogue with paintings from the permanent collection.

One of the most fascinating focuses of the exhibition concerns the figure of Prince Odone of Savoy, fourth son of Victor Emmanuel II. Moving to Genoa in 1861 to alleviate the suffering of a serious degenerative disease, the Duke of Monferrato turned his condition into an intellectual driving force. His physical disability did not curb his thirst for knowledge, which led him to travel and surround himself with intellectuals and artists of the caliber of archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli or sculptor Santo Varni. Odone’s heterogeneous and rich collection ranged from numismatics to naturalistic artifacts to contemporary art purchased largely at the Promoter Societies’ exhibitions. Upon his untimely death in 1866, his father donated the entire collection to the Ligurian city, respecting his son’s wishes and thus forming the first nucleus of Genoa’s modern civic collections. In the room dedicated to him, visitors can admire works that testify to the prince’s eclectic taste, such as the romantic landscapes by Pasquale Domenico Cambiaso or the sculptures by Santo Varni, among which L’amore che doma la forza, commissioned by Odone himself, stands out. Also of particular interest is the recently found plaster cast of L’educazione materna, also by Varni, depicting the noblewoman Teresa Pallavicini Durazzo, a work that combines adherence to the real with formal composure. Odone’s patronage is further celebrated by the bronze monument created by Antonio Orazio Quinzio, cast in 1891, which depicts the prince seated in an armchair surrounded by his beloved collectibles, such as a tanagrina and a red-figure amphora, artifacts that were exceptionally displayed alongside the statue for the occasion.

Parallel to the royal figure of Odone, the exhibition investigates other profiles of collectors who shaped the taste of the period, such as Filippo Ala Ponzone. A Lombard aristocrat and patriot, he arrived in Genoa as a political exile after the uprisings of the Roman Republic. His presence in the city was marked by a sometimes erratic but impressive patronage: he was a partner in the Promotrice with a larger shareholding than even the king and commissioned numerous works from Santo Varni, with whom he had a troubled professional relationship. His figure, melancholy and subject to sudden changes of mood, well represents the restlessness of a ruling class in transition. Although his plans to settle permanently at Villa Durazzo in Cornigliano and gather his collection there foundered with the sale of the property to the Savoys, a small nucleus of his works nevertheless reached the civic collections, including paintings of patriotic significance such as Carlo Arienti’s The Prophet Jeremiah.

No less important was the role of the Duchess of Galliera, Maria Brignole-Sale, a central figure in Genoese and international philanthropy. The exhibition highlights the duchess’ connection with sculptor Giulio Monteverde, author of the monument dedicated to her and placed in front of the hospital she founded. Interestingly, the artist, having been unable to have the duchess pose in his lifetime, relied on a photograph taken by Nadar in Paris in 1888 to create her posthumous effigy. The Dukes of Galliera, in their luxurious Parisian mansion on the rue de Varenne, collected major works ranging from French Romanticism to contemporary sculpture, many of which later became part of the Genoese heritage, such as Monteverde’s “Jenner” or Camillo Pucci’s historical paintings.

The exhibition then offers an insight into theevolution of pictorial genres, with special attention to landscape painting, which in Genoa experienced a season of profound renewal thanks to the “Gray School.” Artists such as Tammar Luxoro, Alfredo D’Andrade and Ernesto Rayper abandoned academic rhetoric to embrace the study from life, favoring silvery tones and lyrical atmospheres. This change was also fostered by comparison with the Tuscan Macchiaioli, whose works began to circulate in the Promotrice exhibitions, influencing local taste toward greater attention to light and color. Alongside the landscape, genre painting documented everyday life with a new anecdotal realism, visible in works depicting domestic interiors or popular scenes, giving artistic dignity to even the most humble subjects.

A key chapter of the review is devoted to sculpture and the Staglieno Cemetery, a true open-air museum that in the second half of the 19th century became the city’s main tourist attraction, admired by intellectuals from all over Europe. Staglieno, a mirror of the “city of the living,” saw the triumph of bourgeois realism, with monuments celebrating the values of family, work and economic success. Artists such as Augusto Rivalta and Giovanni Scanzi translated the likeness of a rising entrepreneurial class into marble and bronze, sometimes with an almost photographic verism. The exhibition evokes this season through sketches and related works, also recalling the figure of Vincenzo Vela and his monument to Cavour, destroyed by bombing in 1942, whose marble head remains on display: a work that provoked debate at the time for its anti-academic realism, portraying the statesman in an informal pose.

Continuing along the chronological path, the exhibition takes us toward the end of the century, a period marked by theItalian-American Exposition of 1892, organized for the fourth centenary of the discovery of America. That event, which transformed the Bisagno esplanade into a celebration of industrial and cultural progress, saw a massive participation of artists at the Palace of Fine Arts. In this turn-of-the-century context, Ligurian art opened up to the instances of Symbolism and Divisionism, well represented in the exhibition by Plinio Nomellini’s grand canvases, such as Il cantiere and Nuova gente, examples of social symbolism. The section also documents the Mitteleuropean influence, with works inspired by Böcklin and Von Stuck, and the sculpture of Leonardo Bistolfi, whose funerary monuments for Staglieno marked the shift toward a more mysterious and spiritual conception of death, overcoming realist descriptivism.

The exhibition does not neglect the dynamism of the art market, analyzing the workings of the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti. Founded in 1849, this institution became the economic and cultural engine of the sector, enabling the purchase of works through subscriptions and lotteries and fostering the meeting between the traditional aristocracy and the new entrepreneurial bourgeoisie. The Promotrice’s annual exhibitions ensured a constant circulation of extra-regional works and artists, breaking cultural isolation and fostering a fruitful interchange with the Tuscan, Piedmontese and Lombard schools of painting.

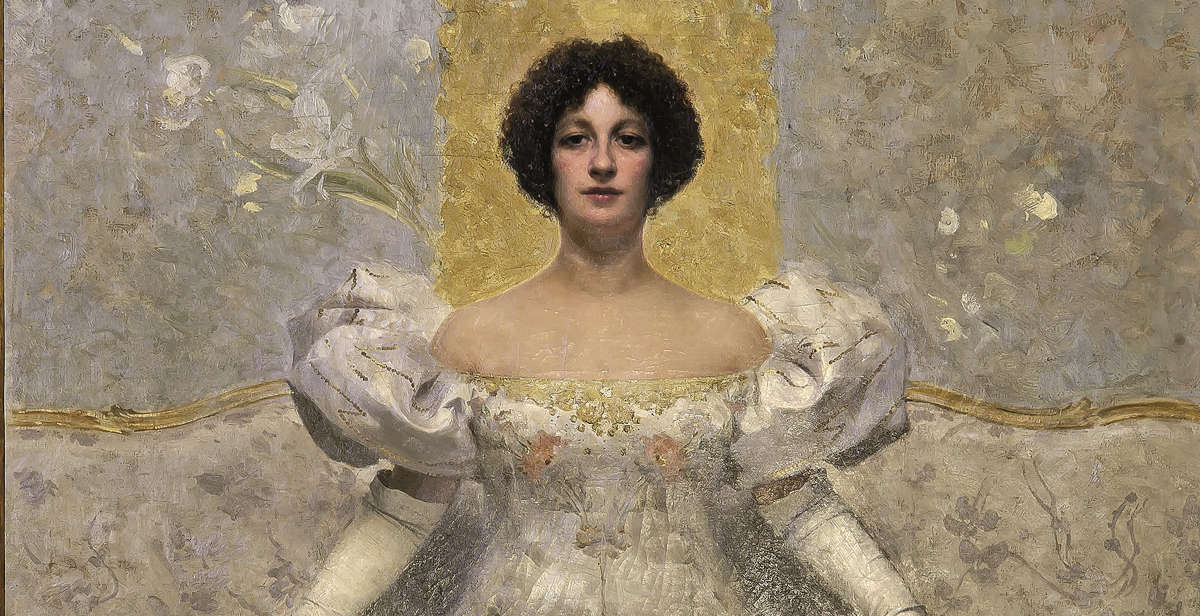

Finally, the section of the Frugone Collections, which documents significant episodes of private collecting, such as the affair of the portrait of banker Giuseppe Bianchi executed by Tranquillo Cremona in 1872, deserves a specific in-depth look. The work, which originated in a context of Milanese business relations, testifies to the scapigliato artist’s passage to Genoa and the often complex dynamics between patron and painter. Similarly, the presence of works by Giacomo Grosso, such as the scandalous La femme, purchased by Count Ottolenghi, illustrates how the Genoese market at the end of the century was receptive to new works, thanks in part to the activity of private galleries such as that of photographer Ernesto Rossi.

Ottocento svelato is thus configured not only as a series of exhibitions, but as a wide-ranging cultural operation that, through the recovery of forgotten works and the reinterpretation of known ones, restores to Genoa the leading role it had in the artistic panorama of the 19th century. From aristocratic portraiture to social verism, from princely to bourgeois patronage, the project offers contemporary visitors the key to understanding the roots of modernity in a city that was a crossroads of cultures, capitals and talents. The exhibitions will remain open to the public until spring 2026, accompanied by a rich scholarly catalog and educational activities designed to involve the entire citizenry in rediscovering its history.

|

| Genoa rediscovers the 19th century: a journey through hidden masterpieces and the revolution of the real thing |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.