A drawing by Rembrandt van Rijn (Leiden, 1606 - Amsterdam, 1669) depicting a young lion has made art market history by becoming the Dutch artist’s most expensive work on paper ever sold at auction. The sheet, known as Young lion resting (“Young lion resting”), fetched $18 million (15.25 million euros) at Sotheby’s New York on Feb. 4, far surpassing the previous record for a Rembrandt drawing, which stood at $3.7 million. A result described as extraordinary by insiders, confirming the growing attention of collectors to the graphic masterpieces of the great masters and the independent value of the drawing as an accomplished work.

Created in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Young Lion at Rest was offered with an estimate of between $15 million and $20 million (€12.7 million to €17 million), a range that already hinted at the work’s exceptional nature. Prior to the sale, the drawing was the subject of a lengthy international tour that took it on display in Paris, London, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong, and Diriyah. This route reflects Sotheby’s strategy of strengthening its global presence, particularly in Saudi Arabia, after holding its first auction in the country last year.

The work occupies a very special position in Rembrandt’s output. It is in fact the only depiction of an animal by the Dutch master still remaining in private hands and the first, after more than a century, to appear on the market. For more than two decades, the drawing has been part of the Leiden Collection, one of the world’s most important private collections devoted to 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art. The collection includes at least seventeen paintings by Rembrandt and also holds the only work by Johannes Vermeer still in a private collection, shaping itself as an absolute benchmark for the study of the Dutch Golden Age.

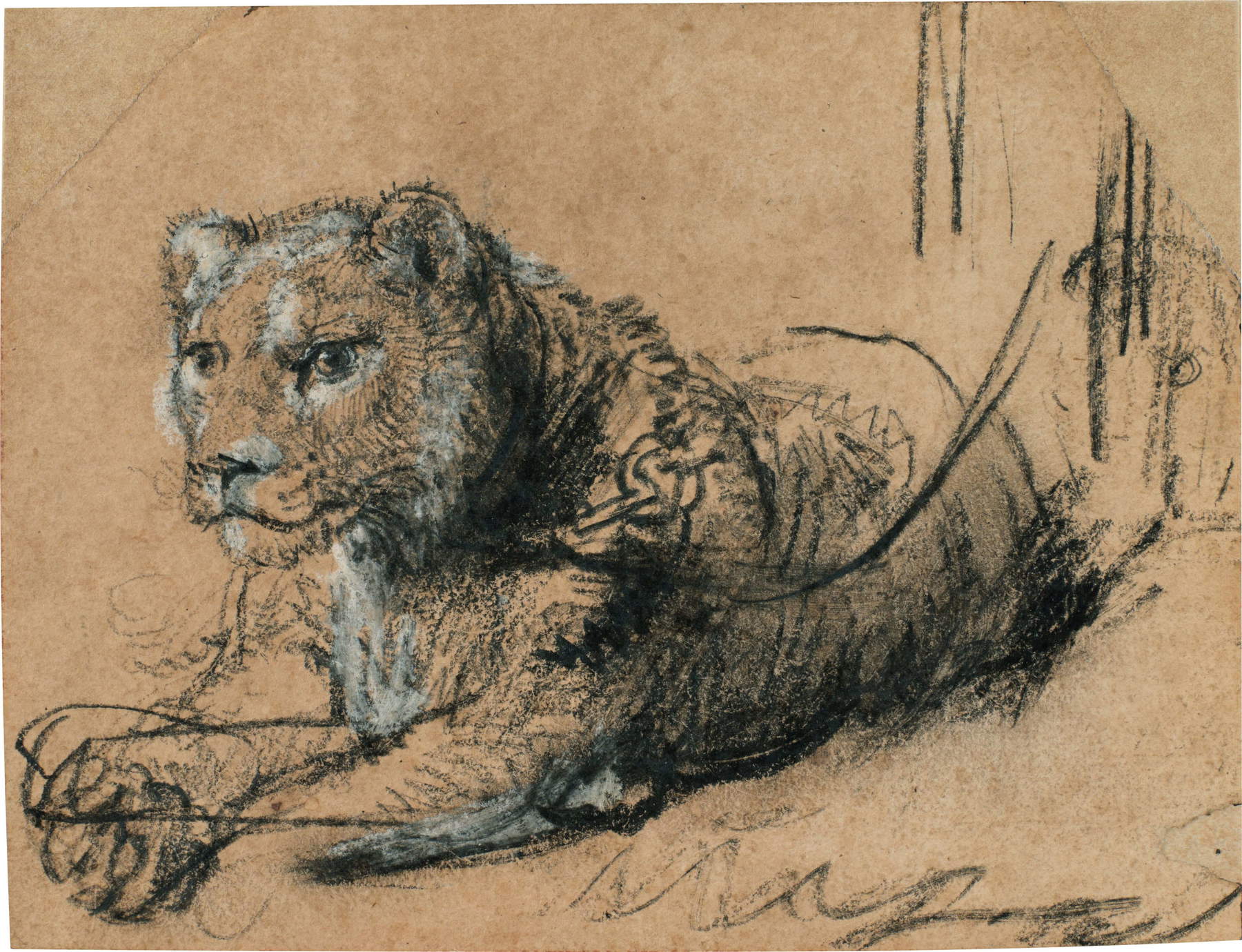

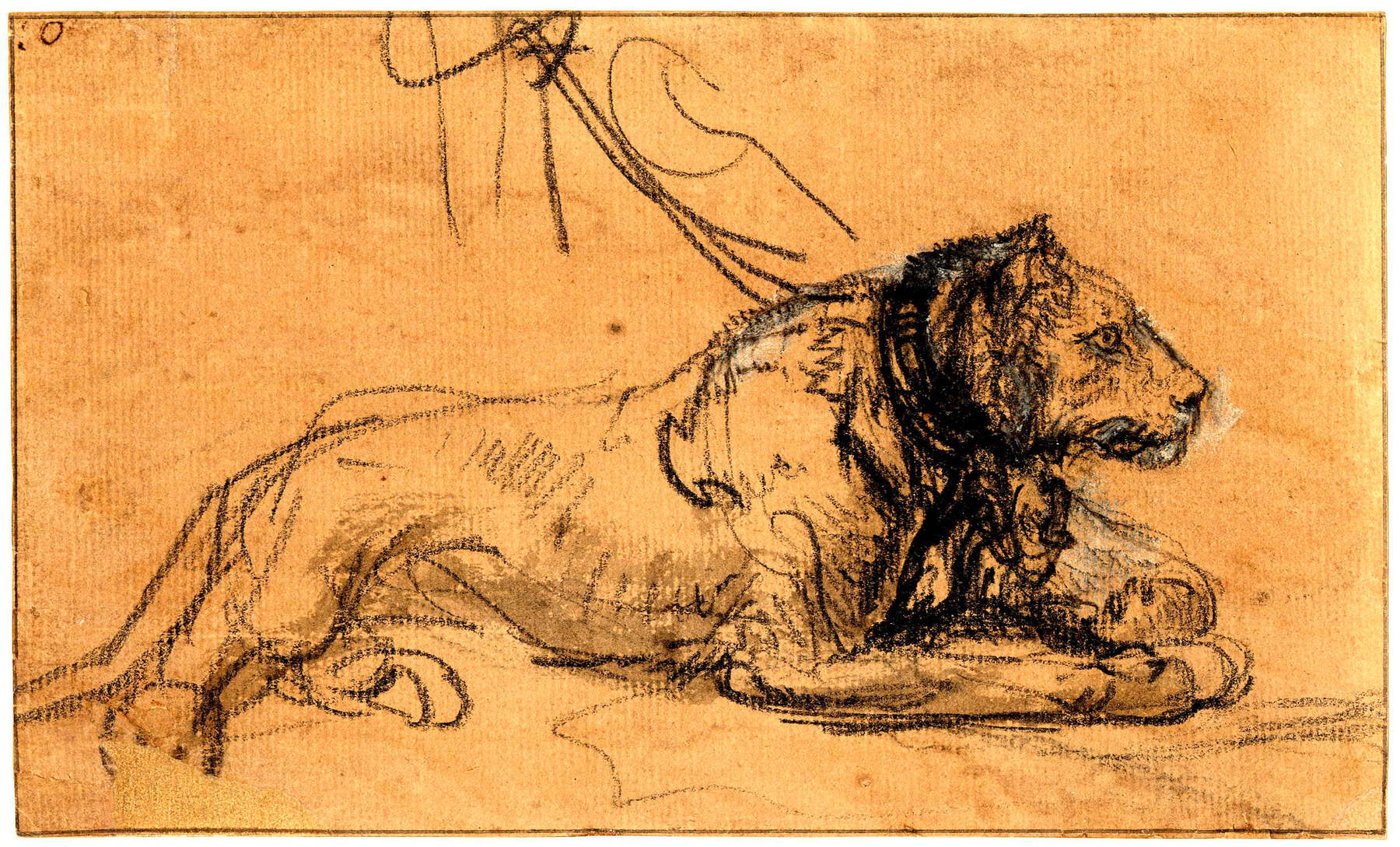

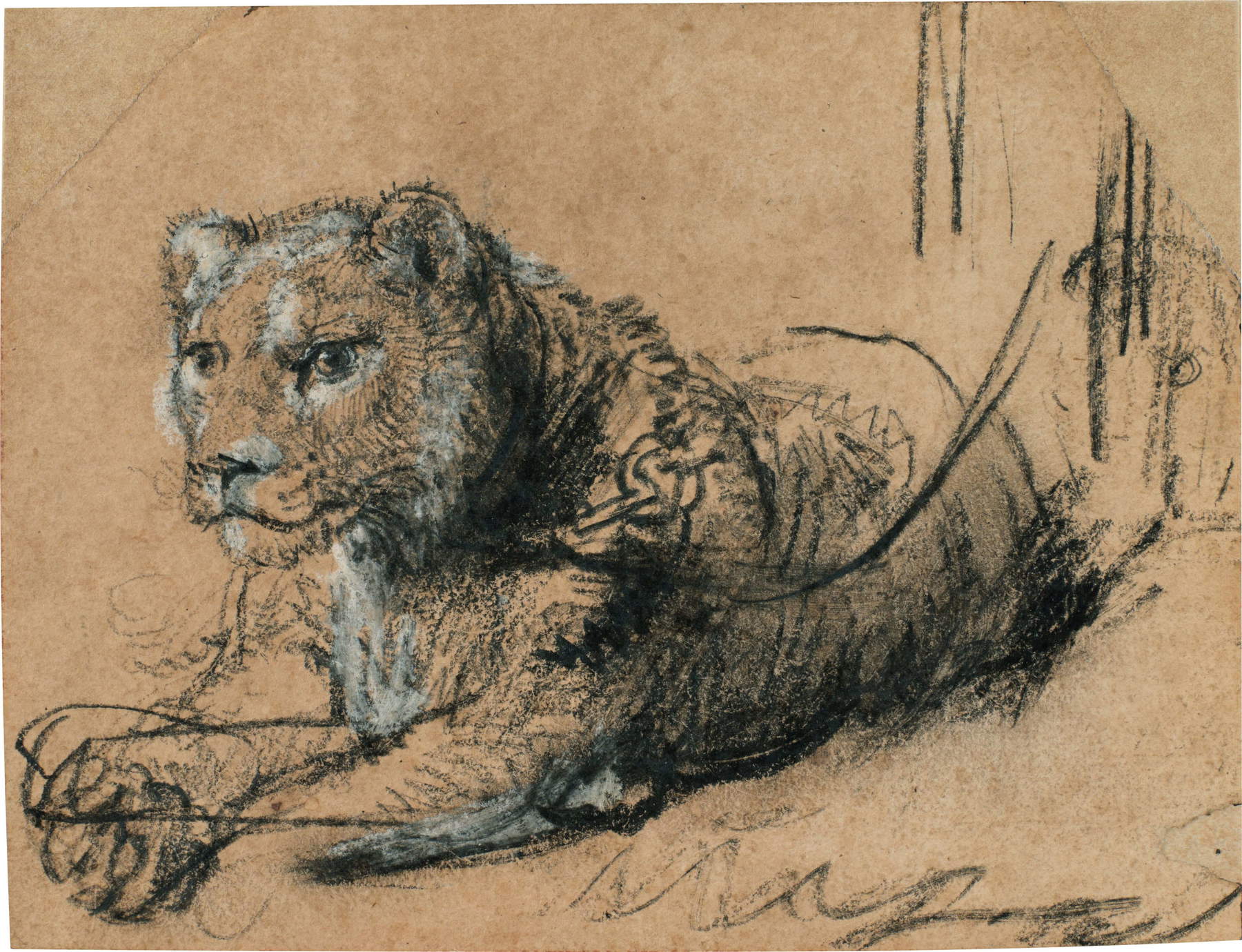

The young lion depicted by Rembrandt is caught in a pose of only apparent rest. The drawing, clearly executed from life, renders all the power, nobility and restless vitality of the animal. With just a few strokes of chalk and quick brush strokes, the artist succeeds in blending direct observation of nature with an extraordinary capacity for psychological penetration. The lion’s gaze, turned slightly to the left of the viewer, concentrates a tension that makes the image at once calm and charged with energy, as if the animal could snap at any moment.

From a technical point of view, the drawing is characterized by an extraordinary spontaneity of execution, particularly evident in the left front paw, drawn in two different positions. This solution reveals the very process of observation and drawing, restoring the immediacy of the artist’s first glance at the subject. In a few lines Rembrandt does not merely describe the lion’s outward appearance, but seems to grasp its deeper essence, transforming the animal study into a true portrait, comparable in intensity to those devoted to human subjects.

The choice of drawing as a medium of expression is central to the work’s impact. Freed from the layered mediation of painting, the image records the artist’s most direct gesture, allowing the viewer to share in the original act of observation. It is a concentrated moment, charged with tension and awareness, that makes Young Lion at Rest one of the most intense sheets in Rembrandt’s entire graphic production.

Proceeds from the sale go to support Panthera, the world’s leading organization dedicated to the conservation of wild felines. The link between the work and this cause reinforces the symbolic value of the drawing, which combines the historical image of the lion, an animal that has always been charged with cultural and political significance, with the concrete protection of today’s endangered species. When Dr. Thomas S. Kaplan, founder of Panthera and the Leiden Collection, acquired Young Lion at Rest in 2005, the drawing represented his first purchase of a Rembrandt work. That acquisition marked the beginning of a collecting journey that would lead to the creation of one of the most important private collections of Dutch Golden Age art in existence today. Over time, the Leiden Collection has also become known for its scholarly approach to the study of works and a policy of lending that has enabled museums around the world to exhibit masterpieces rarely accessible to the public.

Panthera was founded in 2006 by the shared vision of renowned wildlife biologist Alan Rabinowitz and philanthropist Thomas Kaplan. The organization’s mission is to secure a future for wild felines and the vast territories on which they depend by promoting coexistence between humans and animals and protecting natural landscapes through science-driven initiatives. Panthera’s work today represents the most comprehensive and structured global effort to conserve the forty existing species of wild cats. The organization works with local communities to combat poaching, combat illegal wildlife trafficking and safeguard critical habitats. In parallel, it conducts intensive outreach to raise awareness of the threats facing big cats and to ensure their survival for future generations. The organization can count on more than seventy field scientists with doctorate- or master’s-level training, as well as law enforcement experts from fields such as the armed forces, intelligence services, police, and criminological sciences, setting itself up as a unique entity in the landscape of targeted species protection.

From an art historical perspective, the Young Lion at Rest is one of only six drawings of lions attributed with certainty to Rembrandt that have come down to us. The others are all preserved in museum collections in London, Paris, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Although only fifteen of Rembrandt’s animal drawings are known today and, indeed, only six of lions, it is likely that he made more. Studies such as this would have been essential to deepening his understanding of the natural world and his ability to incorporate its elements quite convincingly into his compositions of other kinds.

According to a catalog of his collection compiled around 1722, the art dealer Jan Pieterszoon Zomer (1641-1724) owned nineteen drawings of lions by Rembrandt, although it is likely that among these were drawings then believed to be by Rembrandt but which we now consider to be the work of one of his pupils. Several such drawings, copied from Rembrandt originals or made around the same time, have survived, and in addition Constantijn van Renesse (1626-80), a pupil of Rembrandt around 1650, made a drawing with lions based on those drawn by his master in a portrait of Daniel in the lion’s den. Later still, in 1729, Bernard Picart (1673-1733) published his Recueil de Lions, a series of 42 prints depicting lions, eighteen of which are identified as taken from drawings by Rembrandt, perhaps those previously owned by Zomer.

To date, it is not yet possible to determine with certainty the path each followed before emerging at various times between the 18th and 20th centuries in the Netherlands, France and England. According to the archives of the Netherlands Institute of Art History (RKD) in The Hague, Young Lion at Rest was part of a significant group of Rembrandt drawings in the collection of French artist Jean-Jacques de Boissieu (1736-1810), who was strongly influenced, especially in his engraving, by the works of his illustrious Dutch predecessor. It later belonged to the charismatic French dealer and collector Robert Lebel (1901-1986), a friend of André Breton and Marcel Duchamp’s first biographer: the last part of his collection was sold by Sotheby’s in Paris in 2009.

The sheet in the Leiden Collection is notable for its combination of materials, including a particularly dense black chalk, probably mixed with an oily binder, interventions of gray wash, and touches of white for the points of maximum light, applied on a lightly toned paper. Comparison with the two famous drawings of lionesses in the British Museum reveals such technical and stylistic similarities as to suggest that they may have been made on the same occasion. However, in the sheet sold by Sotheby’s, Rembrandt chooses a three-quarter view that accentuates the dynamism of the composition and focuses attention on the animal’s face and eyes. It is precisely the gaze, of extraordinary intensity, that is the emotional key to the drawing. The body is drawn with broad, rapid lines, while the head is rendered with shorter, more controlled strokes, creating a contrast that amplifies the tension between apparent stillness and potential aggression.

The generally accepted view that the Young Lion at Rest in the Leiden Collection and associated drawings held in the British Museum date from the late 1730s or early 1740s is based both on stylistic comparisons with other Rembrandt drawings from this period, and on the suggestion that there is a connection, however vague, between these drawings of lions and Rembrandt’s spectacular, if enigmatic, monochrome painting of 1637-45, known as The Concord of the State, preserved in the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. In the left foreground of that painting, a prominently positioned lion, which would have been immediately recognized as a symbol of the Dutch state, lies chained in a manner reminiscent of the present drawing, snarling at the viewer. Although no surviving drawing can be considered a direct study of the lion in this painting, the generally similar way in which it lies and is bound has been interpreted as an indication that the black chalk drawings predate the completion of the painting. It should be noted, however, that there is a world of difference between the absolutely realistic way in which the lions in the drawings appear, lie, and appear to move, and the much more unrealistic appearance of the lion in the painting, which does not, in all honesty, give the impression that the person who painted it ever saw a real lion.

The presence of the chain around the lion’s neck, connected to a rope leading off-screen, is a reminder that the animal is in captivity, a detail that heightens the sense of restrained menace. In this aspect, the drawing finds affinity with other depictions of lions made by Rembrandt in the same years, while it departs from them in terms of extreme naturalism compared to the lions that appear in some of his paintings and engravings, which are often more symbolic than observed from life.

The historical context in which Rembrandt might have studied a live lion remains a subject of research. Documentary sources indicate that in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, the presence of exotic animals was rare and mainly related to fairs, traveling shows , or small commercial menageries. Rembrandt’s is probably a Berber lion, from North Africa. It is easy for a modern observer to assume that exotic animals like this were readily available to an artist as interested as Rembrandt, but this was by no means the case in 17th-century Holland. As one of the world’s major maritime and trading powers, the Dutch had close ties during this period with many remote locations, from New Amsterdam (now New York), to Central America and Brazil, to West and Southern Africa, to Southern India and Sri Lanka, to Indonesia and present-day Taiwan. From all these places, exotic objects, minerals, plants and animals were brought back to Holland, both for commercial reasons and to further scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that it was extremely difficult to safely transport a large wild animal for long distances, and the most exotic specimens were only rarely sighted.

Some of the animals brought to the Netherlands were taken around to the fairs and festivals that were regularly held throughout the country, kept in tents or mobile cages, to be admired by paying customers. Others entered fixed menageries set up by aristocrats on their country estates, although the main examples of these menageries, including that of Prince William V at Het Loo Palace, were not established until the late 17th or early 18th century. More frequently, animals that were not taken from one place to another were made available for viewing in small commercial menageries housed in the courtyards of inns, such as Blauw Jan’s on the Kloveniersburgwal in Amsterdam, which was the most prominent place of its kind in the city, or the smaller “Witte Oliphant” (“White Elephant”) on the Botermarkt. Whenever the owners of these facilities purchased a new animal they thought would be of interest, they would post an announcement on a poster, encouraging the public to come and see the new attraction.

It seems that lions were exhibited more regularly in Amsterdam than elephants, although even the latter were probably only seen once every few years. According to Laurien van der Werff of the Rijksmuseum, the two most important sources of information about the presence of lions in the Netherlands at the time are the 46 volumes of handwritten diary notes of the German-born scholar, librarian and mayor of Harderwijk, Ernst Brinck (1582-1649), and the archives of the Amsterdam Spinhouse, the charitable organization that received part of the proceeds from the fairs held in the city, where exotic animals were often exhibited. Brinck was extremely interested in exotic animals, noting down more or less everyone he saw during his travels, although unfortunately he did not always provide exact dates. We do know, however, from his notes that in 1644 and again in 1645 a young lion was seen in Amsterdam, and that unspecified lions were seen in Harderwijk, Delft and Amsterdam in 1646 and 1647, and Roscam Abbing tells us that both a lion and a lioness were exhibited at the Hague Fair in 1648. In 1649, Brinck notes that an old lion was exhibited in Amsterdam, and it is possibly the one depicted in Rembrandt’s drawing in the Louvre.

Although no document has so far been located that would allow us to determine with certainty when Rembrandt made his extraordinary drawing of a Young Lion at Rest, it is clear from these sources that lions were visible in Amsterdam at various times in the mid-1640s, and most likely even earlier, and that a young lion was exhibited in both 1644 and 1645. In addition, annual fairs where these animals could be seen were held in what is now Waterlooplein, just a two-minute walk from the house in Jodenbreestraat that was purchased by Rembrandt in 1639 and now houses the Rembrandthuis Museum.

The success of The Young Lion at Rest thus takes on significance beyond the economic record. On the one hand it consecrates one of Rembrandt’s most important drawings as an absolute masterpiece in the market for works on paper; on the other it directly links art history to a contemporary cause of global significance. The drawing has also been requested for the exhibition Rembrandt’s Lions: Art and Exile in the Dutch Republic, scheduled to run at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York from October 23, 2026 to January 31, 2027, confirming its central role in the study of the Dutch master’s graphic work.

|

| Rembrandt, a record-breaking lion: it is his most valuable drawing ever sold at auction |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.