A man walks through downtown Vancouver carrying something in a paper bag. We also see him in profile as, in another moment of the story in which he is both protagonist and extra, he talks to a woman leaning against the wall of a house. A second woman-wearing the same color coat, an electric blue, as the messenger with the mysterious delivery-in a later frame crosses paths with another man who, in a different shot, seems to be waiting for someone while a sign warns that pedestrians are forbidden to pass there. In this passage of something unspoken and unspeakable, throw in other random shots, like shots taken by the camera dropped from his hand, and the structure of A Partial Account is complete. Seemingly complete. For although the succession of images is reminiscent of the strip of a noir comic strip, or the predella sequence of a Renaissance polyptych, and although the second part of the title of the lightbox in diptych form even tells us the day and hour of the staging(A Partial Account of events taking place between the hours of 9.35 a.m. and 3.22 p.m., Tuesday, January 21, 1997), this work by Jeff Wall, but in general all the work of the Canadian artist, leaves the door wide open to the unspoken, the indefinite, the mysterious. Ultimately, to the personal interpretation that each viewer can derive from those visual cues. And this of the work open to the gaze of others, who complete it by giving it a meaning with their own experience, is one of the main poetic lines of Jeff Wall, protagonist until March 8 of an important solo exhibition in Bologna at the gallery of Fondazione Mast, the Manifattura di arti, sperimentazione e tecnologia born in 2013 and focused on the photography-industry binomial.

The other preponderant and surprising aspect of the discourse in images that the Vancouver-born photographer, born in 1946, has been pursuing since the 1970s is the autonomy of art from the reality that surrounds us. Not that the 28 large works that make up the exhibition Living, Working, Surviving, set up on two floors of the exhibition space on Via Speranza in the suburban Santa Viola neighborhood, are divorced from the present. The images, in fact, were extrapolated from posing sets along city streets in Canada, as in California or Turkey. But there is a bearing at once conceptual and ideal, theoretical rather than chronachistic, that situates the artist’s work in a pictorial rather than a photographic context, as if her compositions would find a suitable place in a baroque picture gallery rather than a digital portfolio.

For that matter, it was Jeff Wall himself who confessed this to Urs Stahel, the curator of the solo show that is at once a succinct anthology of a journey ranging from the lightbox with the water digger in The Well from 1989, granted by the Glenstone Museum (Washington, D.C.), to the 2021 inkjet print lent by the Gagosian Gallery depicting a woman in a yoga pose sunbathing on the roof of a car(Sunseeker, the only work something to glamorize in a context of works that are anything but): “I don’t do storytelling, nor am I interested in storytelling,” the artist revealed, “because the construction of an image,” he added during the press conference on the day of the opening, “has something pictorial about it and is about composition, light, volumes, shapes, colors.” Far from storyteller, instead an old-fashioned artist’s ideology.

Jeff Wall was trained in the context of North American minimalist and conceptual art. But he almost immediately opted for a format of commercial and advertising derivation, such as photography applied to lightboxes. And if the first, in 1978, of these backlit photos had an essential, monochrome setting-followed in the same year, however, by the Stanza distrutta, which explicitly quotes Delacroix’s The Dead of Sardanapalo (“anepochal work” for Walter Guadagnini, author of the book A History of Photography in the 20th and 21st Centuries) - , the external and extreme social reality of suburban Vancouver, where Wall has his studio, soon took over. Thus the cast of photographic sets became populated with homeless and outcasts, with gasoline thieves(Siphoning fuel, 2008), but also with mechanics grappling with an engine to be repaired(Men move an engine block, 2008), with cleaners in an anonymous hotel(Housekeeping, 1996). Or of sympathetic, smiling meat packers(Dressing Poultry, 2007) in a makeshift butcher shop, far removed from the hygienic standards of Western sanitation and where the Canadian Nas seem never to have set foot. And it is precisely this gigantic 201-by-252-centimeter image - in a size that rivals those of the great canvases of American art, neo-expressionist and then pop, according to a choice made programmatically by the Canadian artist who has shifted the perimeter of photography from book to museum, from slides to lightboxes, from representation to real life emulated at times by the 1:1 of the protagonists - to connect with the great tradition of genre painting, with Vancouver’s aged and ramshackle butchers appearing direct heirs of Bernardo Strozzi’s Pollarola.

In the construction of his complex film sets, which are important in determining the duration of an image that is actually still, Jeff Wall does not employ people from the trade, nor does he hire Hollywood stars to amplify the media effect of the work as is the case in Francesco Vezzoli’s videos and staging. If we were to find a parallel with the world of cinema for this author who, because of his chosen subjects, could be likened to the world of the least told in Ken Loach’s films, we would have to think of neorealism with its non-professional actors. Such is, in fact, the boy who arrived in 1997 from a village in Turkey to Istanbul and whom Wall enlisted to ask him to repeat for countless takes his arrival on foot with his duffel bag at a crossroads between two country roads. Like a modern Hercules at the crossroads, that Turkish migrant is the only human presence in a landscape that stretches as far as the eye can see between fields, farmhouses and, in the distance, the endless skyline of the advancing metropolis.

Two-thirds of this view of Turkey (granted for the exhibition by the Pinakothek of Modern Art in Munich: several public and private collections involved in the project, from France to Portugal, from Germany to the U.S., as well as major galleries such as Lorcan O’Neill, Gagosian, White Cube, Marian Goodman) are dominated by a milky sky furrowed by the intertwining wires of an old-fashioned power grid, yes, but useful for drawing a portion of the “abstract” image where the rest is of a heightened and lyrical (neo)realism. In Wall’s reality and imagery, the sky can be white from the mugginess, as in the derelict suburbs of River Road, a 1994 lightbox in which the river cannot even be seen, or blue and furrowed by clouds to give a little hope to travelers (actually dignified homeless people moving their few, poor belongings) who cross theOverpass in Vancouver in 2021 with their trolleys and hopes (the work is in the same Mast collection).

There is also room in the Bologna exhibition for simple objects, such as buckets of paint - a metaphor for painting under the guise of still life Staining bench, furniture manufacturer’s, Vancouver , 2003 - or for uninhabited interiors that look like an Arte Povera installation: the abandoned cold storage with still ice on the ceiling between the bare concrete pillars of Cold storage, Vancouver, 2007, in icy black and white, the other palette of the master of backlit colors. But certainly the choice of landscape-never idyllic or even exasperatingly stark-is central to the choice made by artist, curator and commissioner for the exhibition at Mast. In the metaphysical suspension into which Jeff Wall transports his very real fiction, 1994’s A Hunting Scene stands out: at the edge of a suburban road, with houses and trees crowning a field full of weeds and garbage, two hunters move about with rifles in their hands. And it remains for the viewer to complete the task by wondering whether these are two poor people looking for food on the edge of the city that has eaten its lawns or, in the wake of so much independent cinema denouncing racism, whether the prey is not, instead, human. And, incidentally, the exhibition’s catalog, published by the Mast Foundation, reveals that after hundreds of shots, the artist chose only in postproduction the exact positions of the two hunters, in a manner opposite to that of the street reporter and more in keeping with the modus operandi of a vedutista of yesteryear.

Jeff Wall, according to curator Urs Stahel, is not exactly a neo “painter of modern life” like Baudelaire. Rather, the scholar calls him a “visual interpreter of postmodern, late-capitalist life.” And to his heroes, women and men who have survived the deadly mechanism of the savage market, the Canadian artist often bestows the honor of secrecy. As in the Renaissance iconography of the Rückenfigur, the protagonists of Wall’s hyper-realistic pictorialism are, in fact, very often seen from behind: in “acting” their part, that is, they offer the back of their heads and hide their faces from the viewer. Instead, she puts on her face, not her back, the girl left in the doorway of a poor wooden house in the gigantic (in size and impact) 1997 silver gelatin print that the mile-long title tells us was executed at two different times: Rear, 304 E25th Ave, May 20 1997, 1.14 & 1.17 p.m. Placed at the end of the exhibition’s itinerary, this work, granted by the Meert Gallery in Brussels, contains a secret, a double image that alludes to a hole, a bug, in the reality depicted. There is a picture within a picture, as if it were a picture within a picture on the model of Velázquez’s Las meninas . With Manet he is another of the great masters to whom Jeff Wall has looked to for his immersion out of time but into bright, blinding, searing contemporary reality.

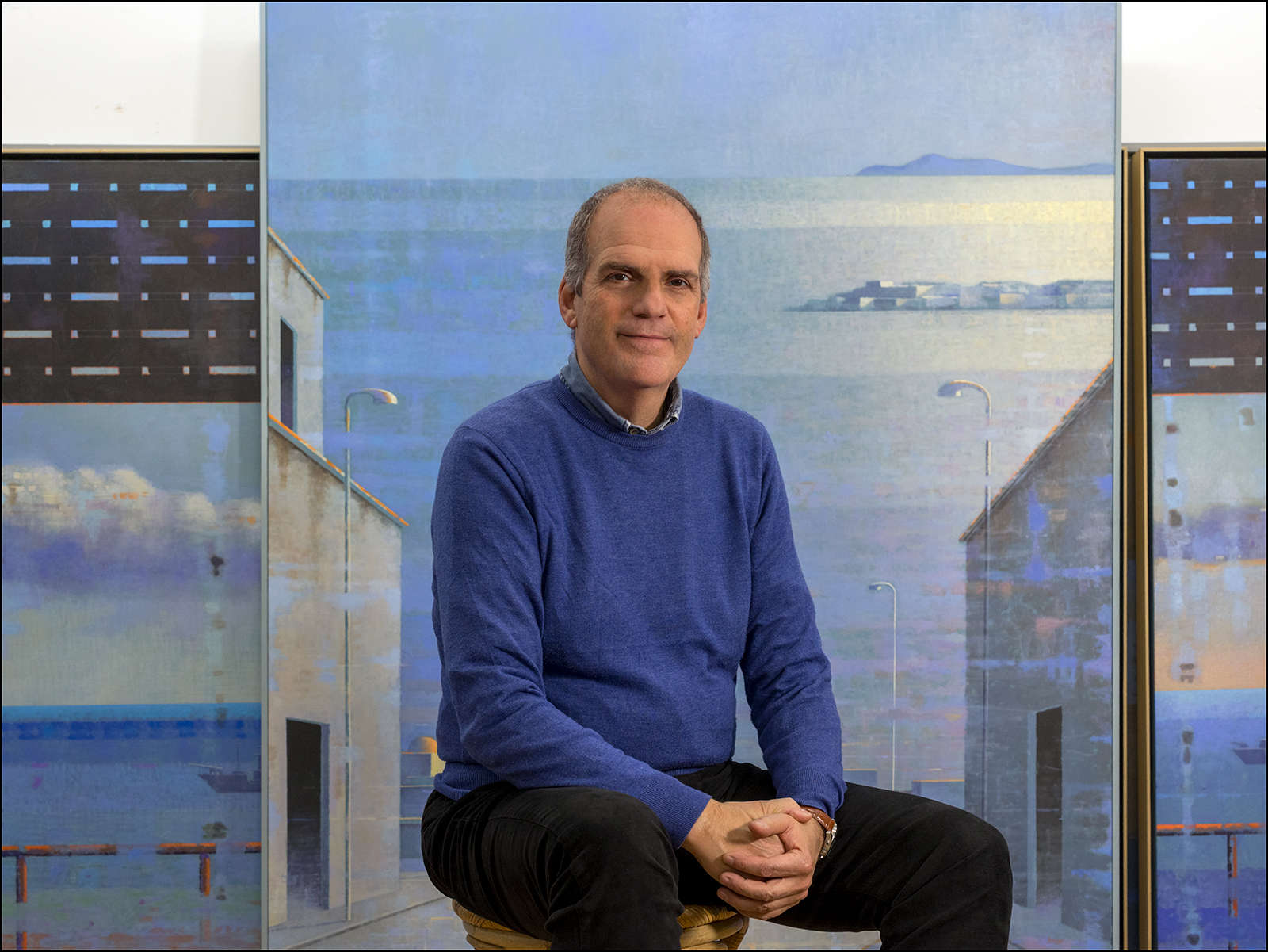

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.