What is the meaning of curating contemporary art today, understood as a practice of connecting and surfacing the present? In this interview with Gabriele Landi, Maurizio Coccia, Director of the Center for Contemporary Art Palazzo Lucarini in Trevi (Perugia) and professor of Contemporary Art History at the Academy of Fine Arts in Perugia, reflects on the role of the curator, rejecting the idea of authoritarian leadership and defining himself rather as a facilitator of connections, attentive to the stratifications of the present and the thought processes that result in artistic actions. Central is the human relationship with artists, based on empathy and trust, as well as an “omnivorous” conception of visual languages, far from specialisms and hierarchies. The interview also addresses the theme of the ethical responsibility of the intellectual, the relationship between art and politics, the state of contemporary art in Italy and the experience of the shared direction of Palazzo Lucarini, returning the portrait of a curatorial practice rooted in reality and open to dialogue.

GL. How did your interest in art and especially contemporary art come about?

MC. It happened a bit by accident. I have always been fascinated by the humanities. From a very early time. Growing up, then, I focused on the visual expressions of creativity. Not only art, but also architecture, design and advertising graphics. Meanwhile working there After graduation, by a series of fortuitous coincidences, I entered the art system until the decisive meeting with Giancarlo Politi. And from there, everything changed.

What studies did you do?

I graduated in Pedagogy, from the University of Parma. At the time there was no Faculty of Letters and Philosophy nor one in Conservation of Cultural Heritage; therefore, for the sake of maximum approximation, I set my curriculum on all the available art-historical disciplines. In the end, therefore, I think I followed a cross-curricular path among the humanities-philosophy, sociology, psychology..., plus the whole repertoire of characterizing subjects by studying art history under the granitic aegis of the legendary Arturo Carlo Quintavalle. All this resulted in my becoming a happily “mestizo” art historian, but without improper eclecticism.

Were there any important encounters during your formative years that somehow had an influence on the development of your work?

I don’t want to sound rhetorical, but with each new encounter I feel that I have acquired something more. I am more charged with tension and stimulation. I remember that Edgar Morin once wrote “...I have become all that I have encountered.” There, it is a formula in which I recognize myself. Or rather, it is an incessant osmotic attitude that I cannot - nor do I want to - change. That said, I certainly owe a great deal to Giancarlo Politi. His generosity and “romantic pragmatism” have helped and influenced me greatly. Another fundamental meeting was with Getulio Alviani. What I know, about the technical and scientific aspects with respect to mounting exhibitions, I owe to him. I remember a very intense day spent in the mounting of a large exhibition of Chinese artists, during which he tested my patience, but he transmitted to me a unique wealth of knowledge and indications-sometimes dazzling-about the perception of the exhibition space, which still direct me today. I must then add another episode, not strictly related to the art world, but which nevertheless left the deepest mark. I was still at university and one day, in Parma, I met Derek Walcott, who would shortly thereafter become Nobel Prize winner for Literature. I always carried with me, folded in my wallet, one of his poems. I showed it to him and asked for his autograph, we exchanged a few words, and he greeted me, smiling. There, that willingness of his, the enormity of his genius clothed in humility, made me realize that the great, the true Greats, do not need to protect themselves with arrogance or snobbery. They don’t have to prove anything to anyone.

How do you understand your work?

I do not interpret the role of a curator as that of a leader in the ideational and realization process of exhibitions. Rather, I see it in the same way as a geologist faced with the stratification of the present. I stimulate - I try to, at least - emergencies, I propose connections, I highlight unseen associations. Sometimes I have insights that I try to share with artists or subjects who in various ways seem to me suitable to become active interlocutors. But I rarely pursue an aesthetic or formal strand a priori. It’s probably a limitation of mine, but I prefer - let’s say, instinctively - transversal thought processes, and anchored in reality, that materialize in artistic “actions.” And everything from exhibitions to talks to conferences to workshops can fit under this definition.

In the babel of contemporary visual languages, is there anything you favor and what attracts you to these languages?

Everything. Seriously, I am culturally omnivorous. For a very long time, in fact, it is no longer time for specialism or philological obsessions. I have no aprioristic preference. In the introduction to the 2001 Venice Biennale catalog, Harald Szeemann wrote that he aspired to a history of art under the profile of intensity. So would I like it too. An encyclopedic but empirical narrative of what has artistic energy and coherence. A narrative of the time in which I live, without imposed hierarchies: high and low, painting and film, performance and literature, philosophy and sports agonism... Unfortunately, the risk of amateurism is around the corner. Therefore, it takes a lot of care and passion to stay true to the grammatical precision of art.

How do you approach an artist’s work?

The human aspect for me is central. Often it is people I have known for a while, whom I “trust.” If there is no empathy feedback behind an interesting work, I leave it alone. Then, anything can happen, of course. But this is the first degree of selection. I hardly patrol social media. Rather, I go through exhibitions and referrals from colleagues or other artists. Of course, there is the academy pool and its inducement. I like to engage with young artists. It always surprises me and helps me grow, every time.

What dynamics does the bicephalic direction of Palazzo Lucarini (shared with Mara Predicatori) follow?

I have known and respected Mara Predicatori for more than two decades. Without her, Palazzo Lucarini would not be what it has become. So far there has been total harmony in the management of Palazzo Lucarini’s programming, lively enriched precisely by our respective idiosyncrasies. The roles, however, as complementary, are different. Besides co-curator of many exhibitions, Mara is in charge of the educational sector, to which she combines tasks (and great ability) in institutional relations. As far as I am concerned, on the other hand, in my capacity as Artistic Director I carry out activities of direction and supervision on the program and collateral initiatives.

Following are questions from some artist friends I have involved in this adventure. Franko B: Do you think art can change the world or is it the world that changes art?

Art, in my opinion, has always accompanied the evolution of humanity. At least on the art-historical level. I don’t think, however, that it has ever played a really active role in change. Unless we go into cultural anthropology. But then we would have to understand the term “art.” Art, however, represents a synthesis of the historical moment-in all its forms-that saw it and stimulated it into being. It is more than an object: it is an action that is as in the world. And as such, it is inscribed in the endless expanse of possibilities. I think it helps us to see reality from a different perspective. In that, if you will, there is a potential for change.

Mario Consiglio: Why have you never expressed an opinion on the ongoing genocide in Gaza?

On social, maybe. Because it’s a kind of activism that doesn’t belong to me and in which I don’t recognize myself. Like most intellectuals who, in spite of everything, are politically engaged. I remember Godard saying, “I don’t make political films, but I make films politically.” Instead, I have participated in public demonstrations and marches. When appropriate, during lectures or in debates, I have always expressed very clearly my disgust and horror at what is happening in Gaza.

Laura Patacchia: What do you think about the situation that the art world is experiencing in Italy today? If you had to write a book about it what title would you give it?

I don’t think it is worse than in the past. The energies are there and social media provide opportunities for enormous visibility. Regarding the quality of the achievements, if we cry, I don’t see other states laughing lightheartedly. What we lack, as always, is serious and solid institutional support that facilitates artistic work in terms of production, knowledge, dissemination. Not only internationally, but here at home: in schools first of all. The title I would like to my book would be, for obvious reasons, a quote from Jim Morrison’s biography, “No One Will Leave Here Alive.” But there would definitely be copyright issues-so, I don’t know. Joking aside, I would prefer something that would incite openness and breaking out of the condition of self-protection and relational strategies that I see rampant, especially among young talent. Something, in short, that had more to do with generosity than career.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

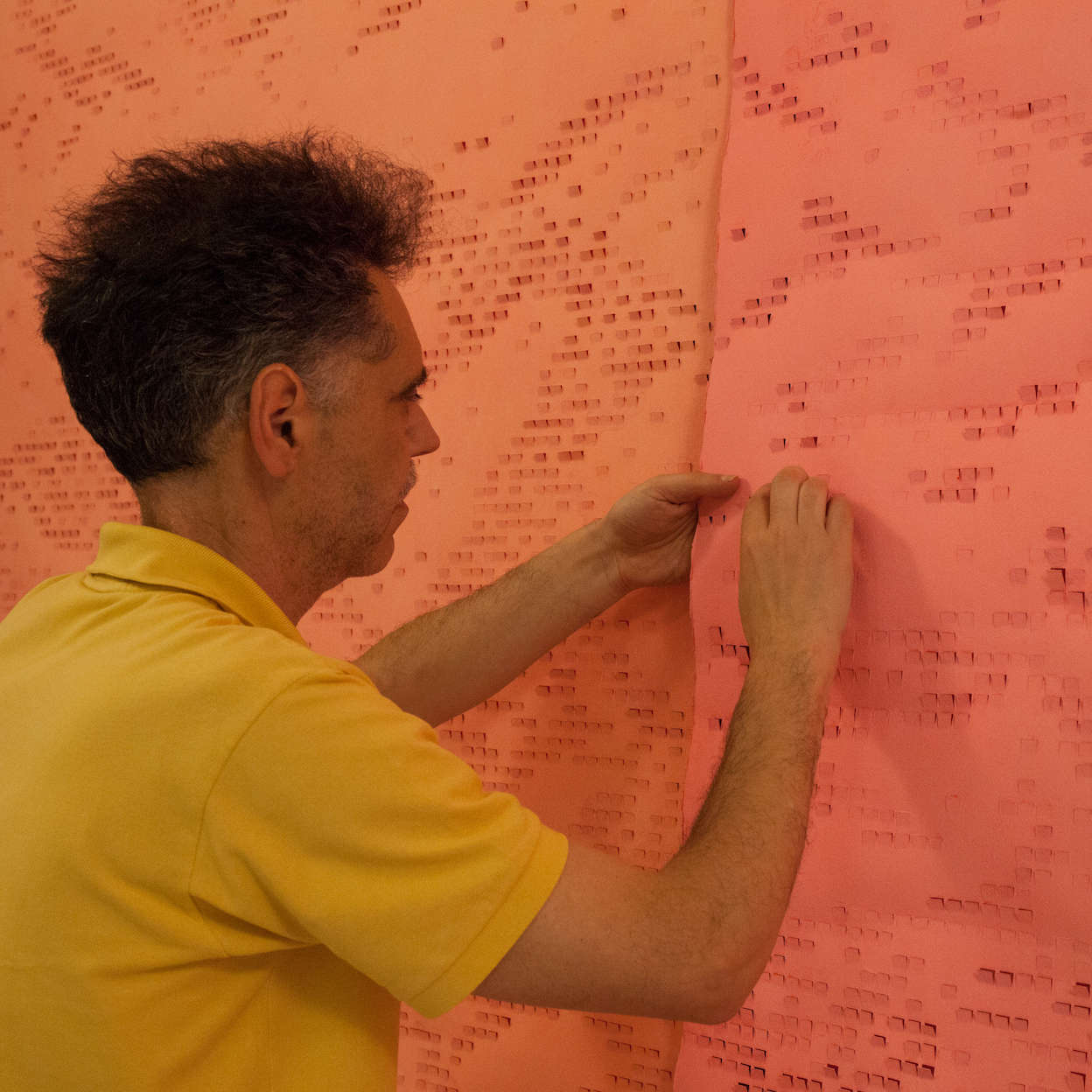

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.